J

Janeway’s lesions

Slightly raised but usually flat, irregular, and nontender, Janeway’s lesions are small (1 to 4 mm in diameter), erythematous lesions on the palms and soles that disappear spontaneously. They blanch with pressure or elevation of the affected extremity; occasionally, they form a diffuse rash over the trunk and extremities.

Janeway’s lesions were once a common finding in those with infective endocarditis, possibly reflecting an immunologic reaction to the infecting organisms (usually bacteria). These lesions are rarely seen today because the disease is now detected and managed at an earlier stage.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If you observe Janeway’s lesions, obtain a medical history from the patient, noting especially valvular or rheumatic heart disease. If the patient has had valvular or rheumatic heart disease, ask about recent dental procedures or invasive diagnostic tests. Does he have a prosthetic replacement valve? Find out about recent meningitis and any skin, bone, or respiratory tract infections. Does the patient have renal disease requiring an arteriovenous shunt? Has he had recent long-term I.V. therapy such as total parenteral nutrition? Ask him to describe how he feels. Does he report weakness, fatigue, chills, anorexia, or night sweats, possibly indicating an infection? Does he have other complaints?

Obtain a drug history. Find out if the patient with valvular or rheumatic heart disease has been taking a prophylactic antibiotic. Ask about I.V. drug use. Note the use of any immunosuppressant.

Next, perform a physical examination. Inspect his skin for other lesions, such as petechiae on his trunk or mucous membranes, and Osler’s nodes on his palms, soles, or finger or toe pads. Inspect his fingers for clubbing and splinter hemorrhages.

Take the patient’s vital signs, noting fever and tachycardia (which may indicate heart failure if it persists after fever disappears). Inspect and palpate his extremities for edema. Auscultate for gallops and murmurs. Assess other body systems for embolic complications of infective endocarditis, such as acute abdominal pain and hematuria. Examining his eyes with an ophthalmoscope may reveal Roth’s spots, another sign of infective endocarditis.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Acute infective endocarditis. Janeway’s lesions are a late sign of this infectious disorder. Early signs and symptoms include a sudden onset of shaking chills and fever, peripheral edema, dyspnea, petechiae, Osler’s nodes, Roth’s spots, and hematuria.

♦ Subacute infective endocarditis. Janeway’s lesions may appear late in this disorder, which has an insidious onset. Early findings include weakness, fatigue, weight loss, fever, night sweats, anorexia, and arthralgia. Other signs and symptoms include an elevated pulse, pale

skin, Osler’s nodes, splinter hemorrhages under the fingernails, petechiae, Roth’s spots, clubbing of the fingers (in long-standing disease), splenomegaly, and murmurs. Embolization may produce acute signs and symptoms, such as chest, abdominal, and extremity pain; paralysis; hematuria; and blindness.

skin, Osler’s nodes, splinter hemorrhages under the fingernails, petechiae, Roth’s spots, clubbing of the fingers (in long-standing disease), splenomegaly, and murmurs. Embolization may produce acute signs and symptoms, such as chest, abdominal, and extremity pain; paralysis; hematuria; and blindness.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Tell the patient that Janeway’s lesions will disappear without damaging his skin. Treatment of infective endocarditis includes an antibiotic and—with complications such as heart failure— a diuretic and cardiac glycoside. Monitor the patient’s intake, output, and cardiac status, and be alert for embolic complications, acute chest pain, abdominal pain, and paralysis. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as blood cultures and an echocardiogram.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

In children, Janeway’s lesions result from infective endocarditis, which commonly stems from congenital heart defects or rheumatic fever.

Jaundice

[Icterus]

A yellow discoloration of the skin, mucous membranes, or sclera of the eyes, jaundice indicates excessive levels of conjugated or unconjugated bilirubin in the blood. In fair-skinned patients, it’s most noticeable on the face, trunk, and sclera; in dark-skinned patients, on the hard palate, sclera, and conjunctiva.

Jaundice is most apparent in natural sunlight. In fact, it may be undetectable in artificial or poor light. It’s commonly accompanied by pruritus (because bile pigment damages sensory nerves), dark urine, and clay-colored stools.

Jaundice may result from any of three pathophysiologic processes. (See Jaundice: Impaired bilirubin metabolism.) It may be the only warning sign of certain disorders such as pancreatic cancer.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Documenting a history of the patient’s jaundice is critical in determining its cause. Begin by asking the patient when he first noticed the jaundice. Does he also have pruritus, clay-colored stools, or dark urine? Ask about past episodes or a family history of jaundice. Does he have nonspecific signs or symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, or chills; GI signs or symptoms, such as anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, weight loss, or vomiting; or cardiopulmonary symptoms, such as shortness of breath or palpitations? Ask about alcohol use and a history of cancer or liver or gallbladder disease. Has the patient lost weight recently? Also, obtain a drug history. Ask about a history of hepatitis, gallstones, or liver or pancreatic disease.

Perform the physical examination in a room with natural light. Make sure that the orangeyellow hue is jaundice and not due to hypercarotenemia, which is more prominent on the palms and soles and doesn’t affect the sclera. Inspect the patient’s skin for texture and dryness and for hyperpigmentation and xanthomas. Look for spider angiomas or petechiae, clubbed fingers, and gynecomastia. If the patient has heart failure, auscultate for arrhythmias, murmurs, and gallops. For all patients, auscultate for crackles and abnormal bowel sounds. Palpate the lymph nodes for swelling and the abdomen for tenderness, pain, and swelling. Palpate and percuss the liver and spleen for enlargement, and test for ascites with the shifting dullness and fluid wave techniques. Obtain baseline data on the patient’s mental status: Slight changes in sensorium may be an early sign of deteriorating hepatic function. (See Differential diagnosis: Jaundice, pages 406 and 407.)

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Agnogenic myeloid metaplasia. This myeloproliferative disorder of the bone marrow may cause jaundice. Its typical effects, however, are associated with anemia, including fatigue, weakness, anorexia, massive splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, purpura, and bleeding tendencies.

♦ Carcinoma. Cancer of the ampulla of Vater initially produces fluctuating jaundice, mild abdominal pain, recurrent fever, and chills. Occult bleeding may be its first sign. Other findings include weight loss, pruritus, and back pain.

Hepatic cancer (primary liver cancer or another cancer that has metastasized to the liver) may cause jaundice by causing obstruction of the bile duct. Even advanced cancer causes nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as right-upperquadrant discomfort and tenderness, nausea, weight loss, and slight fever. Examination may reveal irregular, nodular, firm hepatomegaly, ascites, peripheral edema, a bruit heard over the liver, and a right-upper-quadrant mass.

Jaundice: Impaired bilirubin metabolism

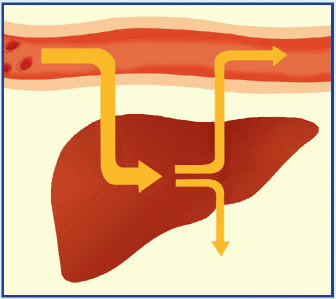

Jaundice occurs in three forms: prehepatic, hepatic, and posthepatic. In all three, bilirubin levels in the blood increase because of impaired metabolism.

With prehepatic jaundice, certain conditions and disorders, such as transfusion reactions and sickle cell anemia, cause massive hemolysis. Red blood cells rupture faster than the liver can conjugate bilirubin, so large amounts of unconjugated bilirubin pass into the blood, causing increased intestinal conversion of this bilirubin to water-soluble urobilinogen for excretion in urine and stools. (Unconjugated bilirubin is insoluble in water, so it can’t be directly excreted in urine.)

|

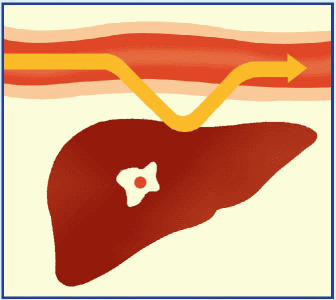

Hepatic jaundice results from the liver’s inability to conjugate or excrete bilirubin, leading to increased blood levels of conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin. This occurs with such disorders as hepatitis, cirrhosis, and metastatic cancer and during the prolonged use of drugs metabolized by the liver.

|

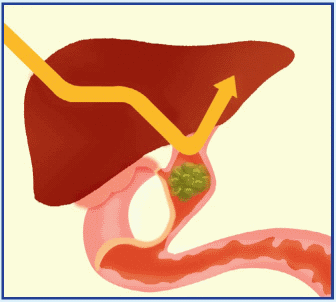

With posthepatic jaundice, which occurs in patients with a biliary or pancreatic disorder, bilirubin forms at its normal rate, but inflammation, scar tissue, a tumor, or gallstones block the flow of bile into the intestine. This causes an accumulation of conjugated bilirubin in the blood. Water-soluble, conjugated bilirubin is excreted in the urine.

|

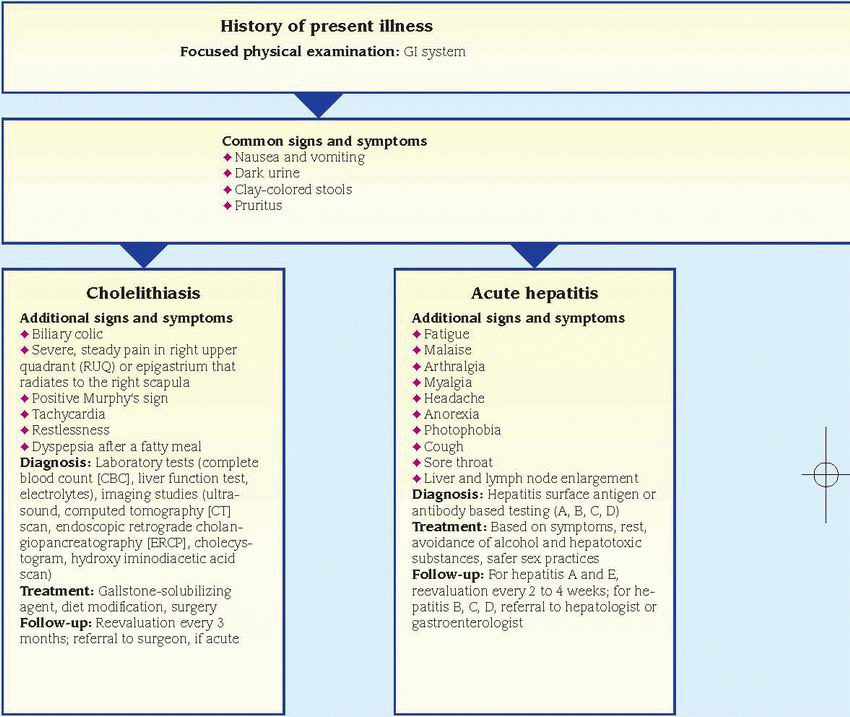

Differential diagnosis: Jaundice

|

|

Additional differential diagnoses: agnogenic myeloid metaplasia ♦ cholangitis ♦ cholecystitis ♦ cirrhosis ♦ Dubin-Johnson syndrome ♦ glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency ♦ hemolytic anemia (acquired) ♦ hepatic abscess ♦ hepatic cancer ♦ leptospirosis ♦ pancreatic cancer ♦ sickle cell anemia ♦ Zieve syndrome

Other causes: androgenic steroids ♦ erythromycin estolate ♦ HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors ♦ hormonal contraceptives ♦ isoniazid ♦ I.V. tetracycline ♦ mercaptopurine ♦ niacin ♦ phenothiazines ♦ portocaval shunt ♦ sulfonamides ♦ troleandomycin ♦ upper abdominal surgery

With pancreatic cancer, progressive jaundice—possibly with pruritus—may be the only sign. Related early findings are nonspecific, such as weight loss and back or abdominal pain. Other signs and symptoms include anorexia, nausea and vomiting, fever, steatorrhea, fatigue, weakness, diarrhea, pruritus, and skin lesions (usually on the legs).

♦ Cholangitis. Obstruction and infection in the common bile duct cause Charcot’s triad: jaundice, right-upper-quadrant pain, and high fever with chills.

♦ Cholecystitis. This disorder produces nonobstructive jaundice in about 25% of patients. Biliary colic typically peaks abruptly, persisting for 2 to 4 hours. The pain then localizes to the right upper quadrant and becomes constant. Local inflammation or passage of stones to the common bile duct causes jaundice. Other findings include nausea, vomiting (usually indicating

the presence of a stone), fever, profuse diaphoresis, chills, tenderness on palpation, a positive Murphy’s sign, and, possibly, abdominal distention and rigidity.

the presence of a stone), fever, profuse diaphoresis, chills, tenderness on palpation, a positive Murphy’s sign, and, possibly, abdominal distention and rigidity.

♦ Cholelithiasis. This disorder commonly causes jaundice and biliary colic. It’s characterized by severe, steady pain in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium that radiates to the right scapula or shoulder and intensifies over several hours. Accompanying signs and symptoms include nausea and vomiting, tachycardia, and restlessness. Occlusion of the common bile duct causes fever, chills, jaundice, clay-colored stools, and abdominal tenderness. After consuming a fatty meal, the patient may experience vague epigastric fullness and dyspepsia.

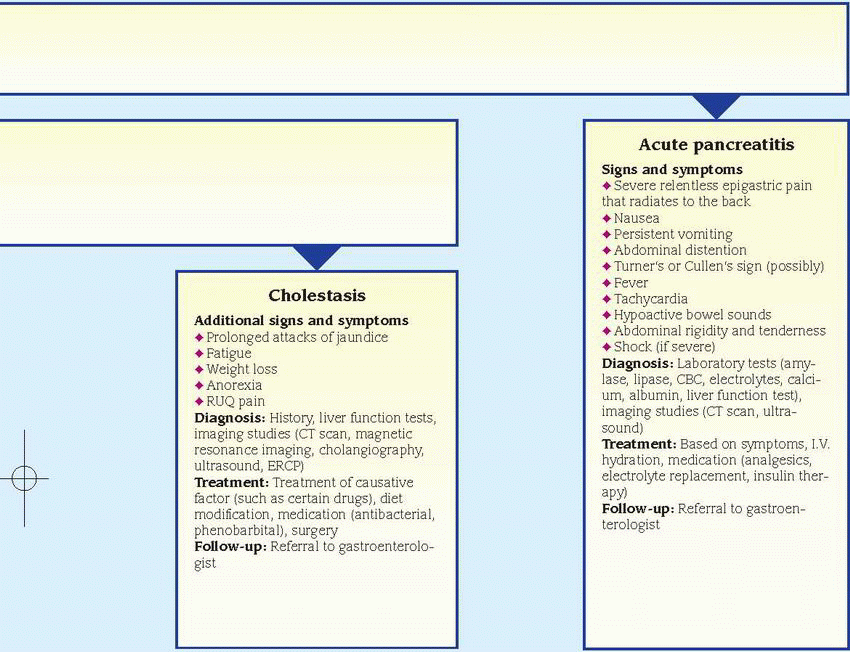

♦ Cholestasis. With benign, recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis, the patient experiences prolonged attacks of jaundice (sometimes spaced several years apart) accompanied by pruritus.

Other signs and symptoms are similar to those of hepatitis—fatigue, nausea, weight loss, anorexia, pale stools, and right-upper-quadrant pain.

Other signs and symptoms are similar to those of hepatitis—fatigue, nausea, weight loss, anorexia, pale stools, and right-upper-quadrant pain.

♦ Cirrhosis. With Laënnec’s cirrhosis, mild to moderate jaundice with pruritus usually signals hepatocellular necrosis or progressive hepatic insufficiency. Common early findings include ascites, weakness, leg edema, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, anorexia, weight loss, and right-upper-quadrant pain. Massive hematemesis and other bleeding tendencies may also occur. Other findings include an enlarged liver and parotid gland, clubbed fingers, Dupuytren’s contracture, mental changes, asterixis, fetor hepaticus, spider angiomas, and palmar erythema. Males may exhibit gynecomastia, scanty chest and axillary hair, and testicular atrophy; females may experience menstrual irregularities.

With primary biliary cirrhosis, fluctuating jaundice may appear years after the onset of other signs and symptoms, such as pruritus that worsens at bedtime (commonly the first sign), weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and vague abdominal pain. Itching may lead to skin excoriation. Associated findings include hyperpigmentation; indications of malabsorption, such as nocturnal diarrhea, steatorrhea, purpura, and osteomalacia; hematemesis from esophageal varices; ascites; edema; xanthelasmas; xanthomas on the palms, soles, and elbows; and hepatomegaly.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree