Treatment of Carotid Aneurysms

M.K. Eskandari

Introduction

Extracranial carotid artery aneurysms are an uncommon entity with an estimated incidence of 0.4% to 4.0% of all peripheral artery aneurysms. Untreated, these aneurysms are associated with a stroke rate of nearly 50% and a death rate as high as 70%. While treatment in the 18th century by Sir Astley Cooper consisted of simple ligation, this approach is rarely employed today. Traditional open surgical techniques as well as endoluminal therapies are available to practitioners as therapeutic modalities. This chapter will focus on the indications for treatment and important technical components of various approaches.

The extracranial carotid anatomy is based on the two common carotid arteries arising from the aortic arch. The right common carotid artery arises from the innominate (brachiocephalic) artery more proximally, which comes directly off the aortic arch, whereas the left common carotid artery arises directly from the transverse aortic arch. On occasion, the left common carotid artery can arise from the innominate artery and this configuration is designated a “bovine arch.” In each case, the common carotid artery bifurcates into an internal carotid and external carotid artery. These vessels can be easily discriminated on arteriography by the presence of branches arising from the external carotid artery in the neck, as compared with the absence, or branches originating from the internal carotid artery throughout its course in the neck. Another important anatomic characteristic to consider with the intracranial portion of the internal carotid artery is that once it enters the skull base the vessel wall is devoid of adventitia and is therefore more fragile than the extracranial segment.

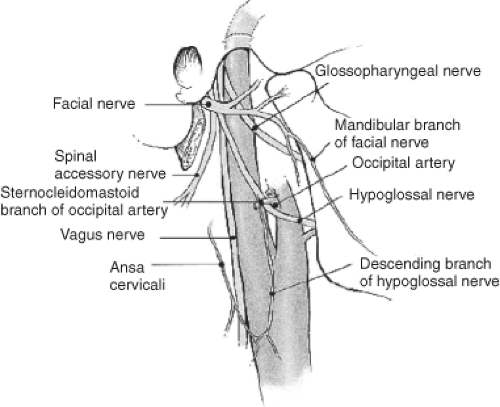

Several cranial nerves are within the vicinity of the extracranial carotid circulation. The vagus (X) nerve traverses parallel and lateral to the carotid and its external fibers form the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The hypoglossal (XII) nerve typically courses transversely and anterior to the internal and external carotid arteries just above the bifurcation. The glossopharyngeal (IX) nerve also passes anterior to the internal carotid, but usually higher in the neck and typically along the length of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. The spinal accessory nerve (XI) passes across the posterior triangle of the neck and is superior. This is rarely encountered in most carotid reconstructions. The marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve (VII) courses with the mandible and may be injured by excessive manual retraction of the mandible, resulting in an asymmetric smile (Fig. 1).

Pathophysiology

As with most other peripheral arterial aneurysms, extracranial carotid aneurysms are generally divided into true and false aneurysms and no direct correlation between atherosclerosis and carotid aneurysm formation has been demonstrated. True aneurysms are further subdivided into fusiform and saccular aneurysms. Fusiform aneurysms represent a generalized weakness of the entire circumference of the arterial wall, whereas saccular aneurysms occur when a focal area of the arterial wall degenerates. The common carotid artery at the bifurcation is the most frequently reported site of true aneurysm formation, followed by the internal carotid artery, and lastly the external carotid artery. It is important to note that clinicians must consider an infected aneurysm as an etiology when a saccular aneurysm is identified.

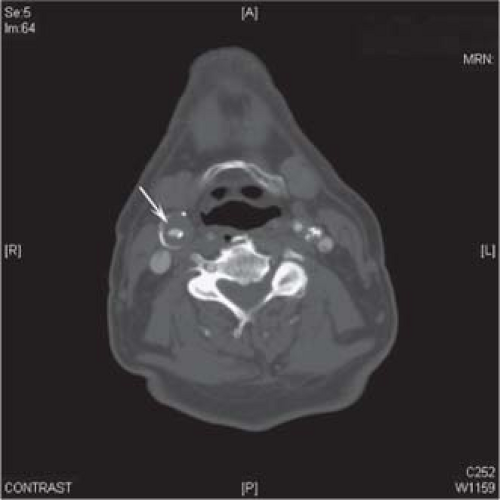

Unlike true aneurysms, false aneurysms, also commonly called pseudoaneurysms, do not have all the layers of the vessel wall involved. Typically, pseudoaneurysms arise from blunt or penetrating neck trauma, catheter-related iatrogenic injury, or following remote carotid endarterectomy along the suture line (Fig. 2). Both blunt and penetrating trauma cause localized intimal tears in the vessel wall and can predispose to early and late pseudoaneurysm formation most commonly in the distal internal carotid artery just before it enters the skull base. Other less common causes include fibromuscular dysplasia, syphilis, cystic medial necrosis, pregnancy-related aneurysms, and granulomatous disease.

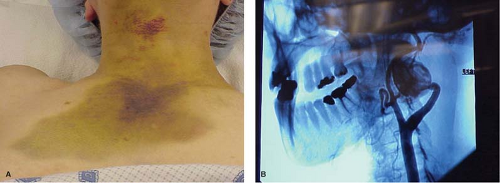

The majority of patients with carotid aneurysms are men with a mean age of 50 to 60 years. Carotid aneurysms may present either with or without symptoms. Fortunately, the majority of patients present with only a pulsatile neck mass just below the angle of the mandible without neurologic compromise. A small percentage suffer from a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke attributed to the release of embolic particulate debris that has accumulated in the dilated aneurysmal lumen. In rare cases, an aneurysm can rupture and cause airway compromise (Fig. 3). Other notable local symptoms range from compression of the esophagus, trachea, oral cavity, or cranial nerves. Horner’s syndrome (miosis, ptosis, anhidrosis), dysphagia (CN IX), hoarseness (CN X), or motor abnormalities of the tongue (CN XII) or shoulder (CN XI) are some of the clinical manifestations of cranial nerve impairment that have been described. While most common carotid artery aneurysms present outwardly in the neck, internal carotid artery aneurysms can present inwardly into the back of the pharynx. As such, an internal carotid aneurysm can be mistaken for an intraoral or retropharyngeal “abscess” and an unsuspecting attempt to incise the “abscess” can lead to massive bleeding.

In the presence of a pulsatile neck mass the diagnosis of a common carotid aneurysm is suspected. Palpation along the course of the extracranial carotid artery will usually locate a readily mobile pulsatile mass. This is in contrast to a carotid body tumor, which is generally only mobile in the lateral plane. Additional noninvasive imaging is required to confirm the diagnosis. Those aneurysms arising from the internal carotid artery, particularly aneurysms close to the skull base, are more difficult to diagnose on physical examination or duplex imaging and often require cross-sectional imaging for identification.

Fig. 2. Computed tomographic angiography of a common carotid artery patch aneurysm with extensive intramural thrombus. |

Duplex ultrasonography is the easiest and least expensive modality to investigate the carotids. Duplex imaging provides accurate

diameter measurements, can assess the luminal contents of the aneurysm, and characterize the type of aneurysm (fusiform vs. saccular). Criteria have been described defining aneurysms as those with at least a diameter measurement that is twice the normal adjacent proximal vessel.

diameter measurements, can assess the luminal contents of the aneurysm, and characterize the type of aneurysm (fusiform vs. saccular). Criteria have been described defining aneurysms as those with at least a diameter measurement that is twice the normal adjacent proximal vessel.

Fig. 3. A: Ruptured left internal carotid aneurysm. B: Angiography demonstrating left internal carotid aneurysm. |

At our institution, we routinely obtain a noninvasive contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging study to better assess the relevant anatomy. Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic angiography (CTA) and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) are most commonly preferred. Alternatively, traditional arteriography can be used to visualize the anatomy. Both CTA and MRA provide detailed information about the extracranial, intracranial, and aortic arch anatomy to best formulate a therapeutic strategy.

A primary determinant for recommending surgical or endovascular treatment is based on the clinical status of the patient. In general, all symptomatic patients should have their aneurysm repaired. Symptoms include stroke, TIA, and local compressive symptoms. Repair of asymptomatic aneurysms should be considered if the aneurysm is at least twice the size of the adjacent normal vessel or if there is a suspicion of an infected aneurysm.

Open Surgical Repair/Reconstruction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree