25 Transplantation surgery

Introduction

For many patients, the optimal treatment of their end-stage renal failure (ESRF) is kidney transplantation because it not only improves quality of life but may also confer survival benefits (EBM 25.1). Liver, heart and lung transplantation can be truly life-saving, as often no alternative treatments are available. The two main obstacles to transplantation are overcoming the recipient’s immune response and a shortage of donor organs.

Transplant immunology

The recipient’s immune response to the donor organ

Early events

Inflammation lies at the heart of the rejection process and is activated through early events around the time of transplantation. Brain-stem death and retrieval of organs, as well as cold ischaemic time (while the organ is stored on ice) and a period of warm ischaemia (while the vascular anastomoses are completed) stimulate an early inflammatory response to the transplanted organ. Reperfusion is associated with endothelial activation and the infiltration of inflammatory cells, particularly macrophages. The importance of this early ischaemia reperfusion injury (IRI) in shaping the patient’s subsequent course is illustrated by the superior outcome observed following living donor transplantation, despite more significant major histocompatibility (MHC) mismatching, and the adverse impact of a more prolonged cold ischaemic time on graft outcome. Indeed, the severity of this inflammatory injury modulates the subsequent alloimmune response, generating a ‘danger signal’ which primes the immune response to the transplanted organ. Thus, IRI impacts upon long-term outcome: it leads to a delay in primary graft function, increases acute rejection rates and reduces long-term graft survival (EBM 25.2). The crucial role of IRI in mediating transplant-associated injury has become more apparent as acute rejection rates fall with the introduction of new and highly effective immunosuppressive agents, and has led to an increasing interest in how IRI may be reduced through preconditioning strategies.

Antigen presentation

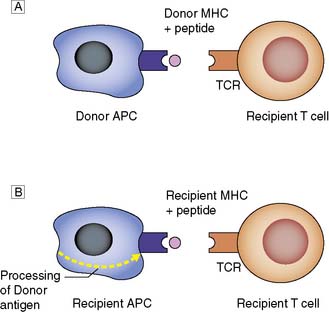

Donor MHC antigens are recognized as foreign (allo- recognition) by recipient T cells following presentation upon donor (direct) or recipient (indirect) antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (Fig. 25.1).

Patterns of allograft rejection

Acute rejection

This occurs in up to 50% of grafts, usually in the first 6 months. Acute rejection is diagnosed on renal transplant biopsy and is classified according to Banff 07 diagnostic criteria (Table 25.1).

Table 25.1 Banff 07 diagnostic criteria for renal allograft biopsies

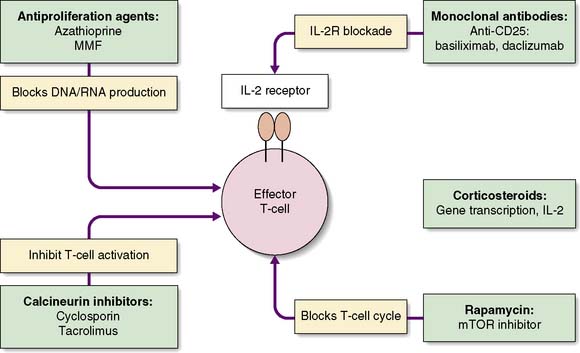

Immunosuppression

The challenge is to minimize the risk of graft rejection with as few side effects as possible. Various strategies are adopted: induction therapy, maintenance immunosuppression and treatment of rejection. The mechanisms of action of the common immunosuppressive drugs are outlined on Figure 25.2.

Immunosuppressive drugs

Steroids

Corticosteroids play an important role in induction and maintenance and are the first-line treatment for acute rejection. The side effects of steroids are numerous and are responsible for many of the long-term complications of immunosuppressive therapy (Table 25.2). This has led to attempts to withdraw steroid therapy some time after transplant, or to minimize their use.

Table 25.2 Side effects of corticosteroids

Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs)

Tacrolimus

Tacrolimus, the second CNI to be introduced into clinical practice, resulted in significantly improved one-year outcome in liver transplant patients (EBM 25.3), and this has been borne out in studies in renal transplantation. Tacrolimus now forms the mainstay of many immunosuppressive regimens. It too carries the risk of nephrotoxicity, and serum levels must be monitored closely. Other side effects include neurotoxicity, diabetes and alopecia.

The future of immunosuppression

Summary Box 25.1 The immune response

• The immune response to a transplanted organ is largely mediated by T cells, and these are the target for immunosuppressive therapy

• Acute rejection is seen in up to 50% of grafts and episodes are treated with high-dose steroids

• Chronic rejection has a multifactorial aetiology and results in significant graft loss over the months and years following transplantation.

Organ donation

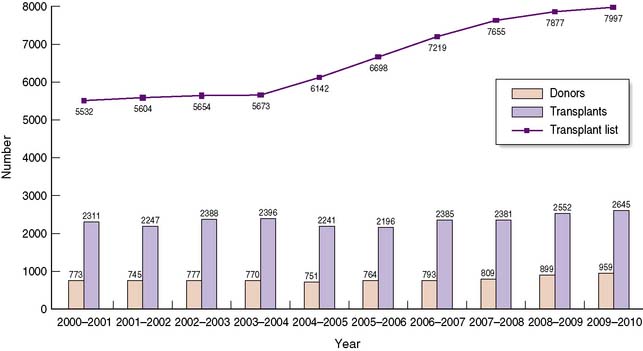

The shortage of organs for transplantation remains a major challenge to the transplant community, with demand consistently outstripping supply over many years (Fig. 25.3). Such a shortage has led to significant changes in practice over the last decade, with an increasing number of patients undergoing transplants from living donors, and from marginal or extended criteria deceased donors. These will be discussed in this section.

Deceased donation

Few absolute contraindications for organ donation exist; those that do are directed against the avoidance of disease transmission from donor to recipient (Table 25.3).

Table 25.3 Donor contraindications to organ donation

| General contraindications • HIV disease (not HIV infection; no AIDS defining illness) • disseminated cancer (above and below the diaphragm) • melanoma (except local melanoma treated > 5 years before donation) • treated cancer within 3 years of donation (except non-melanoma skin cancer and in-situ cervical cancer) • nvCJD and other neurodegenerative diseases associated with infectious agents |

| Organ-specific donor contraindications |

| Liver |

| Kidney |

| Pancreas |

Donor management

Specific criteria must be met in order to make the diagnosis of brain-stem death (Table 25.4). Events leading up to brain death may impact upon the quality of the retrieved organs. Initially, at the point of brainstem death, compression associated with coning results in hypertension and bradycardia, known as the Cushing reflex. An autonomic storm ensues, characterized by the massive release of catecholamines, with resultant hypertension and hypoperfusion. The effect on cardiac function is the deterioration of ventricular systolic function, the liver and kidneys are affected by hypoperfusion, and it is likely that these changes contribute to non-specific endothelial cell damage, which increases the immunogenicity of the organs.

Table 25.4 Criteria for diagnosis of brain-stem death

| Preconditions |

| Exclusions |

| Investigation |

| Absent brain-stem reflexes • No papillary response to light • Absent vestibulocochlear reflexes: caloric tests • No motor response in cranial nerve distribution Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|