Chapter 7 Toxicology

Descriptive toxicology focuses on toxicity testing with the intent of defining the degree of risk associated with substances.

Descriptive toxicology focuses on toxicity testing with the intent of defining the degree of risk associated with substances. Environmental toxicology involves the detection and understanding of environmental pollutants and their effects on humans and other organisms.

Environmental toxicology involves the detection and understanding of environmental pollutants and their effects on humans and other organisms. Forensic toxicology is primarily concerned with detection and quantification of toxic substances for legal purposes.

Forensic toxicology is primarily concerned with detection and quantification of toxic substances for legal purposes. Mechanistic toxicology is focused on determining the mechanisms by which substances exert toxic effects.

Mechanistic toxicology is focused on determining the mechanisms by which substances exert toxic effects. Regulatory toxicology uses toxicologic data to establish policies regarding exposure limits for toxic substances.

Regulatory toxicology uses toxicologic data to establish policies regarding exposure limits for toxic substances.General Principles

Terminology

Toxin, by strict definition, is a poison of biologic origin that does not have the ability to replicate. However, the term toxin has been used more loosely. For example, environmental toxin has been used to describe toxic substances of nonbiologic origin.

Toxin, by strict definition, is a poison of biologic origin that does not have the ability to replicate. However, the term toxin has been used more loosely. For example, environmental toxin has been used to describe toxic substances of nonbiologic origin. Toxicant is a general term that refers to any harmful substance and is generally interchangeable with poison.

Toxicant is a general term that refers to any harmful substance and is generally interchangeable with poison. Toxicodynamics refers to the general concepts of pharmacodynamics (interaction with molecular targets and mechanisms of effects) as applied to interactions and mechanisms that generate toxic effects.

Toxicodynamics refers to the general concepts of pharmacodynamics (interaction with molecular targets and mechanisms of effects) as applied to interactions and mechanisms that generate toxic effects.General Mechanisms of Toxicity

Physical. The physical presence of the toxicant triggers reactions that are harmful (e.g., asbestos fibers in the lung).

Physical. The physical presence of the toxicant triggers reactions that are harmful (e.g., asbestos fibers in the lung). Chemical. Toxicants react chemically with the tissues or body fluids such as blood to produce harmful effects (e.g., strong acids or bases cause burns).

Chemical. Toxicants react chemically with the tissues or body fluids such as blood to produce harmful effects (e.g., strong acids or bases cause burns). Pharmacologic. Toxicants interact with endogenous pharmacologic pathways, resulting in inhibition or overstimulation (e.g., botulinum toxin inhibits release of acetylcholine to cause paralysis).

Pharmacologic. Toxicants interact with endogenous pharmacologic pathways, resulting in inhibition or overstimulation (e.g., botulinum toxin inhibits release of acetylcholine to cause paralysis). Biochemical. Toxicant reacts biochemically with cellular constituents to produce cellular damage (e.g., venom of many snakes contains phospholipases that destroy cell membranes).

Biochemical. Toxicant reacts biochemically with cellular constituents to produce cellular damage (e.g., venom of many snakes contains phospholipases that destroy cell membranes). Genomic (genotoxic). Toxicant alters the genetic material of the cell, resulting in disruption of function. Genotoxic substances may be mutagenic or carcinogenic.

Genomic (genotoxic). Toxicant alters the genetic material of the cell, resulting in disruption of function. Genotoxic substances may be mutagenic or carcinogenic. Mutagenic (carcinogenic). Toxicants alter DNA structure or function sufficiently to cause mutations (benzene) or initiate and promote the development of cancers (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as benzo[a]pyrene, found in cigarette smoke).

Mutagenic (carcinogenic). Toxicants alter DNA structure or function sufficiently to cause mutations (benzene) or initiate and promote the development of cancers (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as benzo[a]pyrene, found in cigarette smoke). Immunologic. Toxicant may trigger an immune response that leads to cellular damage (e.g., penicillin-induced hemolytic anemia) or conversely suppresses the immune system, causing an increased susceptibility to infection (e.g., procainamide-induced agranulocytosis).

Immunologic. Toxicant may trigger an immune response that leads to cellular damage (e.g., penicillin-induced hemolytic anemia) or conversely suppresses the immune system, causing an increased susceptibility to infection (e.g., procainamide-induced agranulocytosis).Target Organs

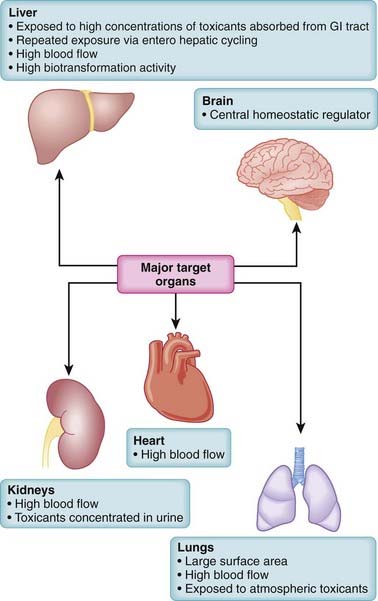

Toxicity may be systemic, affecting the whole body, or it may be largely confined to select target organs, the so-called toxic effect organs. Some organs, such as the liver, brain, lungs, heart, and kidney, play a central role in poisonings (Figure 7-1). When toxicity is site specific, the word toxic is preceded by an indication of the specific target organ. Thus, hepatotoxicity refers to effects on the liver, nephrotoxicity refers to effects on the kidney, ototoxicity refers to effects on the auditory system, and so on. A number of factors interact to determine the susceptibility of organs to toxic effects. These include the organ’s anatomic location, blood flow, metabolic processes and activity, affinity for the toxicant, and capacity for self-repair. Major toxic effect organs include the following:

Liver. The liver is exposed to a high concentration of toxic substances. Orally absorbed toxicants are presented first to the liver via the portal circulation. The liver also receives a large proportion of systemic blood flow. Enterohepatic cycling extends exposure to toxicants excreted through the bile. The high metabolic activity of the liver also results in the generation of reactive intermediates that may have toxic actions.

Liver. The liver is exposed to a high concentration of toxic substances. Orally absorbed toxicants are presented first to the liver via the portal circulation. The liver also receives a large proportion of systemic blood flow. Enterohepatic cycling extends exposure to toxicants excreted through the bile. The high metabolic activity of the liver also results in the generation of reactive intermediates that may have toxic actions. Kidney. The kidney receives a high proportion of the cardiac output. Many toxic substances are excreted by the kidney. These toxicants are concentrated in the urine as fluid is reabsorbed from the renal tubule.

Kidney. The kidney receives a high proportion of the cardiac output. Many toxic substances are excreted by the kidney. These toxicants are concentrated in the urine as fluid is reabsorbed from the renal tubule. Heart. The total blood volume passes through the heart. Thus it is exposed to all blood-borne toxicants.

Heart. The total blood volume passes through the heart. Thus it is exposed to all blood-borne toxicants. Lungs. The lungs represent an extremely large surface area for interaction with toxicants, particularly those that are airborne. The total cardiac output passes through the lungs, so blood-borne toxicants are also distributed extensively to the lungs.

Lungs. The lungs represent an extremely large surface area for interaction with toxicants, particularly those that are airborne. The total cardiac output passes through the lungs, so blood-borne toxicants are also distributed extensively to the lungs. Brain. The brain is a critical target organ because of its central role in homeostasis. Thus toxicants that affect the brain may influence multiple systems and result in widespread systemic toxicity.

Brain. The brain is a critical target organ because of its central role in homeostasis. Thus toxicants that affect the brain may influence multiple systems and result in widespread systemic toxicity.Risk Assessment

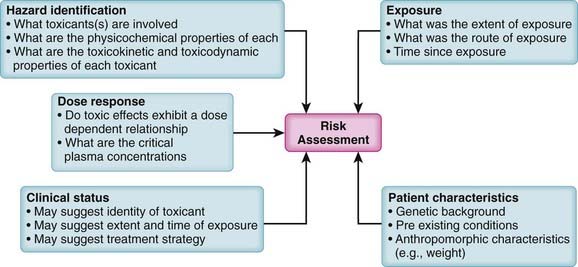

Because virtually all substances are potentially toxic, key questions in toxicology are how much risk is associated with a particular substance and under what conditions does this risk become apparent? In addition, the level of acceptable risk will vary. In some circumstances, very toxic substances (e.g., anticancer drugs) are used therapeutically despite their known toxic effects because the benefits of such treatments outweigh the risks. Accordingly, risk assessment is a primary consideration in the management of toxic events (Figure 7-2).

Key factors contributing to risk assessment include the following:

Hazard identification. What substances are involved and what are the adverse effects of each substance? Knowledge of the physicochemical properties, toxicokinetics, and toxicodynamics of the suspected toxicant(s) is invaluable in designing treatment strategies.

Hazard identification. What substances are involved and what are the adverse effects of each substance? Knowledge of the physicochemical properties, toxicokinetics, and toxicodynamics of the suspected toxicant(s) is invaluable in designing treatment strategies. Dose response. Is there a known dose response relationship for the toxic effects of the toxicant? Do toxic effects mirror plasma concentrations? At what dose (concentration) do toxic effects appear?

Dose response. Is there a known dose response relationship for the toxic effects of the toxicant? Do toxic effects mirror plasma concentrations? At what dose (concentration) do toxic effects appear? Exposure assessment. Exposure assessment is a key process in determining the urgency and strategy for treatment of toxic events. Exposure assessment includes estimation of the following:

Exposure assessment. Exposure assessment is a key process in determining the urgency and strategy for treatment of toxic events. Exposure assessment includes estimation of the following: Route of exposure. The route of exposure is an important determinant of both the extent and rate of absorption of the toxicant. For example, dermal exposure is generally associated with reduced rates and extent of absorption compared with oral ingestion or inhalation.

Route of exposure. The route of exposure is an important determinant of both the extent and rate of absorption of the toxicant. For example, dermal exposure is generally associated with reduced rates and extent of absorption compared with oral ingestion or inhalation. Time since exposure. An estimate of the time since the exposure will be helpful in estimating the following:

Time since exposure. An estimate of the time since the exposure will be helpful in estimating the following: Clinical status. In many cases, information about the degree and time of exposure may be lacking. In such cases, careful determination of the clinical status of the patient coupled with knowledge of potential hazards can assist in determining the type of toxicant (e.g., recognition of anticholinergic effects of mushroom poisoning), the suspected time course, and the treatment protocol. In addition, recognition of compromised airway, circulatory, or neural function requires immediate supportive measures.

Clinical status. In many cases, information about the degree and time of exposure may be lacking. In such cases, careful determination of the clinical status of the patient coupled with knowledge of potential hazards can assist in determining the type of toxicant (e.g., recognition of anticholinergic effects of mushroom poisoning), the suspected time course, and the treatment protocol. In addition, recognition of compromised airway, circulatory, or neural function requires immediate supportive measures. Patient characteristics. The specific characteristics such as anthropomorphic characteristics, genetic background, and preexisting conditions of each patient also factor into risk assessment. Some (e.g., weight) may affect the course of poisoning indirectly, whereas others may have a more direct effect (e.g., alcoholism) by influencing the production or elimination of toxic substances. Genetic polymorphisms may affect absorption, biotransformation, or elimination of toxicants.

Patient characteristics. The specific characteristics such as anthropomorphic characteristics, genetic background, and preexisting conditions of each patient also factor into risk assessment. Some (e.g., weight) may affect the course of poisoning indirectly, whereas others may have a more direct effect (e.g., alcoholism) by influencing the production or elimination of toxic substances. Genetic polymorphisms may affect absorption, biotransformation, or elimination of toxicants.General Strategies for Management of Toxic Events

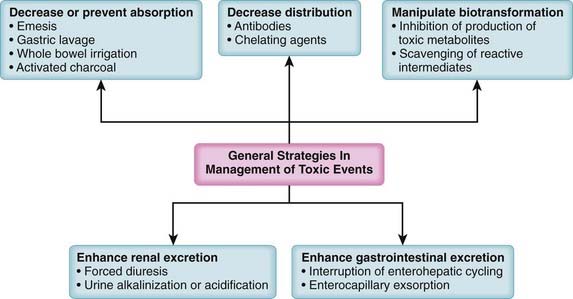

Antibodies that neutralize toxicants or prevent their distribution to target organs (e.g., antivenin for snake bites)

Antibodies that neutralize toxicants or prevent their distribution to target organs (e.g., antivenin for snake bites) Compounds that sequester the toxicant, prevent its distribution, and promote its excretion (e.g., heavy metal chelators)

Compounds that sequester the toxicant, prevent its distribution, and promote its excretion (e.g., heavy metal chelators) Compounds that scavenge the toxicant to prevent its interaction with tissues (e.g., N-acetylcysteine [NAC] in acetaminophen poisoning)

Compounds that scavenge the toxicant to prevent its interaction with tissues (e.g., N-acetylcysteine [NAC] in acetaminophen poisoning) Treatments that act physiologically to oppose the actions of the toxicant (e.g., pressor agents to reverse hypotension)

Treatments that act physiologically to oppose the actions of the toxicant (e.g., pressor agents to reverse hypotension)In addition to specific treatments, a number of generalized treatment strategies can be used in poisonings (Figure 7-3). These are toxicokinetic treatment strategies targeted at reducing or preventing the absorption of the toxicant, at reducing the distribution of the toxicant, at manipulating biotransformation to reduce formation of the toxicant, or at hastening excretion of the toxicant. These approaches rely heavily on the concepts of pharmacokinetics presented earlier, which will not be repeated here. These generalized approaches are very useful in situations in which there are no specific antidotes or the causative toxicant(s) and/or modes of action are not sufficiently well defined to allow application of a specific antidote.

Reduction or Prevention of Absorption

Forced Emesis

Impairment of other GI decontamination procedures since patient may continue to vomit for prolonged period

Impairment of other GI decontamination procedures since patient may continue to vomit for prolonged period Unless a secure (intubated) airway has been established, ipecac should not be used in the following patients:

Unless a secure (intubated) airway has been established, ipecac should not be used in the following patients:Gastric Lavage

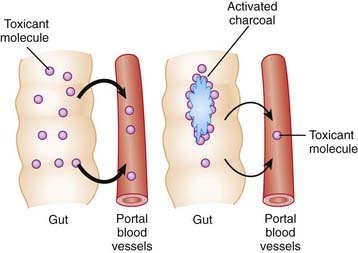

Activated Charcoal

Activation of charcoal by oxidization increases its adsorptive surface area. The large surface area of charcoal is capable of adsorbing many toxicants, thus sequestering them in the gut. Because only free molecules are able to diffuse across membranes, reduction of the concentration of free toxicant in the gut by charcoal greatly reduces absorption into the bloodstream (Figure 7-4). This treatment is administered as a slurry of the activated charcoal powder.