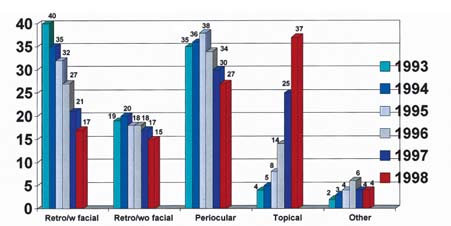

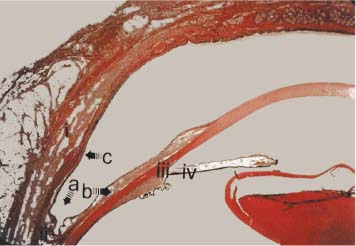

Chapter 2 The development of minimally invasive techniques for cataract surgery has been paralleled by a concomitant development of less invasive anesthesia techniques. These new anesthetic techniques have enjoyed a remarkable increase in usage during the past few years1 (Fig. 2–1). The improvement in both surgical and anesthetic technique is noteworthy for the relative paucity of complications.2 Nonetheless, if these innovative procedures are to produce consistently good results, and avoid complications, we must alter the way in which we approach the patient and the surgical procedure. What has been often called “topical anesthesia” should more suitably be called “noninjection anesthesia,” which encompasses techniques such as parabulbar, subtenon’s, and pinpoint anesthesia, and intracameral techniques. Furthermore, the term topical anesthesia suggests the emphasis on the application of drugs to the ocular surface. In fact, the technique comprises a completely new skill set that requires different patient interaction and sometimes systemic sedation or even general anesthesia. The adjunctive use of intravenous (IV) sedation varies greatly, particularly among geographic regions.3 Perhaps, then, we ought to collectively call this array of ophthalmic anesthetic techniques “topically assisted anesthesia.” An understanding of this global approach is essential to the successful outcome of what we will call “topical anesthesia” from this point on. In contradistinction to common usage, the word anesthesia in the context of intraocular surgery does not simply connote analgesia alone. It encompasses amaurosis, akinesia, sedation, and amnesia.4 The absence of amaurosis and akinesia in patients receiving topical anesthetic with IV sedation, and the absence of all four characteristics in patients receiving topical anesthetic alone, is the hallmark of this multifaceted technique. Retention of vision during and immediately after surgical intervention is not merely window dressing. A parallel exists between the rapid return of visual function and the likelihood of return to activities enjoyed prior to the development of visual impairment.5 Immediate vision, as an index of a successful outcome, is reassuring to surgeon and patient alike. Assessment of immediate postoperative vision can be useful in diagnosing increased intraocular pressure, retinal vascular compromise, and intraocular lens power errors. A brief description of the currently available noninjection and topical anesthesia techniques is useful in understanding the complications that may ensue. Knowledge of the topical anesthetic properties of cocaine date back to the 16th century. Pisarro, the Spanish conquistador, first became aware of these properties in the coca leaf. However, it was not until 1888 that the first human eye anesthesia technique was developed by Karl Koller. He instilled cocaine onto the ocular surface, following the suggestion of his friend and colleague, Sigmund Freud.6–10 While an extremely effective anesthetic, cocaine had significant, sometimes severe, local and systemic toxicity, including severe keratitis and inflammation, hypertension, stroke, and death. Topical anesthetics were later discarded in favor of injectible anesthetics, because of these problems. Additionally, injectible anesthetics provided deep anesthesia and akinesia at a time where comparatively invasive techniques of eye surgery required extensive anesthesia. FIGURE 2–1 Prevalence of topical anesthetic techniques used by members of the ASCRS. (From Leaming.1) In 1991, in concert with the development of increasingly noninvasive cataract surgery techniques, Fine et al11 and Fichman12 described the use of topical lidocaine as being sufficient and effective in cataract surgery. This technique has remained extremely popular, especially in patients undergoing uncomplicated clear cornea surgery. Fichman also later described, and Gills et al13 popularized, the concept of instilling 1% lidocaine MPF (methylparaben free) intracameral anesthetics at the onset of the procedure. This alleviated a frequent complaint regarding topical instillation alone—that it may not always provide sufficient pain ablation, particularly with iris manipulation, or longer cases. Gills and many others found that intracameral instillation alone or as a supplement to topical anesthetics produced an additional measure of anesthesia. Despite the fact that intracameral anesthesia is not, in its strictest sense, a “topical” technique, the approach to the patient using this method is similar to other topical methods and is therefore included in this discussion. Because topical anesthesia alone could be troublesome with more complex or longer cases, I developed a method of anesthesia that combines the safety, comfort, ease of administration, and rapid onset of topical anesthesia with the deep, extensive anatomic distribution of retrobulbar anesthesia.14–17 In Rosenthal deep topical, nerve block anesthesia (RDTNBA) an absorbent cellulose sponge is soaked with an anesthetic mixture of 4% lidocaine MPF and 0.75% bupivacaine MPF in a 2:1 ratio. The sponge is then placed deep in the upper and lower fornices (Fig. 2–2A), and pressurized by the placement of a pressure device such as the Honan’s balloon. This encourages absorption of the anesthetic into both adjacent tissues and posteriorly, thus inducing a nerve block (Fig. 2–2B). Because absorption occurs posteriorly into the peribulbar space (and possibly transconally into the retrobulbar space), the posterior ciliary nerves, which supply the anterior sclera, anterior conjunctiva, and limbus, as well as the iris and ciliary body, are anesthetized at their nerve roots (Fig. 2–3).18–20 The combination of the posterior placement, high concentration of anesthesia, prolonged exposure to the globe, and pressure produces a deep anesthetic effect comparable to injectible techniques. Lidocaine 4% was chosen for RDTNBA because of its low ocular toxicity and its ready commercial availability. In addition, its pharmacology, high potency, and ready absorption across mucous membranes21 (as an amide it tends to bind to protein and is therefore extremely permeable across conjunctival membrane into peribulbar space) are similar to cocaine 4%, but with substantially less ocular toxicity. Its duration of action is adequate for most ocular surgical procedures. Selective supplementation with bupivacaine provides prolonged analgesia to control immediate postoperative discomfort. Experience over 7 years has proven this technique to be comparable to injectible methods22 in production of deep anesthesia for almost all anterior segment surgery.23 FIGURE 2–2 (A) Rosenthal deep topical “nerve block” anesthesia. A cellulose sponge soaked with anesthetic is placed in the superior fornix. (B) Honan’s balloon is applied to press anesthetic sponges against the globe. To provide global ocular anesthesia along with akinesia, without needle injection, several techniques have evolved. These fall into the category of subtenon’s anesthesia and are administered by incising the anterior conjunctiva followed by a posteriorally directed anesthetic injection into the subtenon’s space through a blunt metal cannula. FIGURE 2–3 Histologic section of conjunctival fornix and adjacent structures: i, Eyelid; ii, fornix; iii, ciliary body; iv, iris. Proposed sites of deep absorption are (a) toward peribulbar space, (b) toward the scleral nerves subserving the iris and ciliary body, and (c) into eyelid. (Photomicrograph courtesy of Henry Perry, MD.) In pinpoint anesthesia a long curved, blunt-tipped cannula is inserted into the subtenon’s space and directed posteriorly until it reaches the area adjacent to the optic nerve.24,25 Then the anesthetic agent of choice is injected. This technique provides akinesia as well as anesthesia. Recently, the use of unpreserved topical Xylocaine 2% gel MPF has been introduced.26–28 Application of the gel to the ocular surface prior to starting surgery has been shown to be an effective method of anesthesia for cataract surgery. It also has the added benefit of providing ocular surface lubrication. The gel can be applied for 5 to 30 minutes prior to surgery. No significant ocular surface toxicity has been observed with this method. Additionally the gel anesthetic has proven to be a useful adjunct to the RDTNBA method. The application of a small dollop of gel to the incision at the conclusion of the procedure is extremely effective in alleviating postoperative foreign-body sensation. This is presumably due to its combination of emollient and anesthetic properties. A patient undergoing topical anesthesia will have a different experience before, during, and after surgery, than a patient having injection-based anesthesia. Therefore, in preparation for surgery, it is essential to the successful outcome that the patient receive careful and consistent counseling. The patient must be evaluated as to suitability for this type of anesthetic. Some authors have suggested that there is a correlation between the patient’s pre-operative responses to topical anesthetic drops (such as the “drop then decide” method of Dinsmore29) or to preoperative testing using tonometry and ultrasound.30 In general, patients who are candidates for injectible anesthesia are also candidates for topical anesthetics.31 However, patients who are demented, extremely anxious, psychotic, or with certain movement disorders, as well as children, may not be candidates for any type of local anesthesia, and a general anesthetic with topical supplement should be considered for them. Patients with hearing impairment or language barriers pose special challenges with topical anesthesia.32 Preoperative counseling is essential and a family member or friend can help in translation of information when language barriers exist. A predetermined series of signals should be developed between patient and operating room personnel to allow communications during surgery. Finally, patients with movement disorders should not automatically be excluded from topical, or for that matter, injection anesthetic procedures, because these movements are frequently ablated with sedation. Therefore, only if a tremor persists should a general anesthetic be given. It is important to recognize that the solitary affect of any regional anesthetic, whether administered by needle injection, topical application, or intracameral infusion, is to numb the eye. The role of systemic medication, on the other hand, is to control the behavior of the patient, thus creating an environment in which the patient can be both cooperative and comfortable. Thus, a patient undergoing cataract surgery should receive the minimum amount of systemic medication required to produce anxiolysis, without creating obtundation. Not all patients require IV sedation, and a calm, comfortable patient can have successful surgery without sedation.33 To repeat, regional anesthetics control pain, and systemic agents regulate behavior. As with injectible methods of anesthesia, oversedation of a patient in an attempt to ablate pain is dangerous and inappropriate.34 This may lead to a wildly uncooperative patient and ensuing potential surgical complications.

TOPICAL ANESTHESIA

METHODS OF NONINJECTION ANESTHESIA

TOPICAL DROP

INTRACAMERAL ANESTHESIA

ROSENTHAL DEEP TOPICAL, FORNIX BASED “NERVE BLOCK” ANESTHESIA

SUBTENON‘S OR “PARABULBAR” ANESTHESIA

PINPOINT ANESTHESIA (FUKASAKU)

TOPICAL GEL ANESTHESIA

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT AND GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

PATIENT SELECTION

SYSTEMIC SEDATION:BALANCING THE TOPICAL ANESTHETIC TECHNIQUE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree