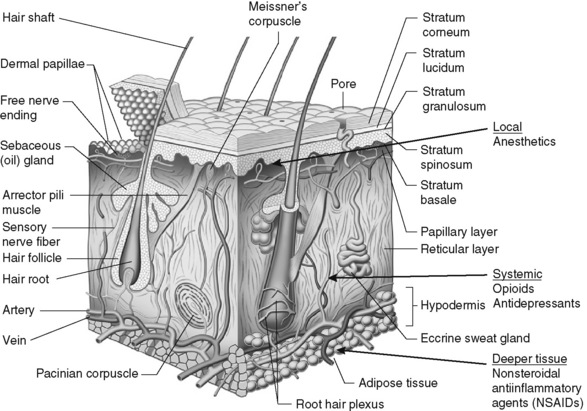

Chapter 24 IT is important to distinguish between the terms topical and transdermal (Stanos, 2007). Although both routes require a drug to cross the stratum corneum to produce analgesia (Figure 24-1), transdermal drug delivery (e.g., long-acting transdermal fentanyl patch) requires absorption to achieve systemic effects, whereas topical agents (e.g., lidocaine patch 5% and other local anesthetics, capsaicin) are intended to produce effects in the tissues immediately under the site of application (Stanos, 2007). Transdermal analgesic drugs provide systemic analgesia, and topical analgesics provide what is referred to as “targeted peripheral analgesia,” or pain relief achieved by “dampening” pain mechanisms within the peripheral nervous system (Argoff, 2003). Transdermal delivery systems typically have a slow onset and extended duration of analgesia. Topical analgesics are faster acting and dissipate relatively soon after removal of the drug. There are significant benefits to using topical analgesics, including patient acceptance, ease of administration, reductions in systemic adverse effects, and fewer drug interactions (Argoff, 2003; McCleane, 2008; Stanos, 2007). Some preparations (e.g., capsaicin, L.M.X.4) can be obtained without a prescription; others (e.g., lidocaine patch 5%, clonidine, EMLA, diclofenac patch) require a prescription. Some topical analgesics (e.g., antidepressants, anticonvulsants, ketamine) are not commercially available but may be prepared by a compounding pharmacy. The topical therapies discussed here are those used primarily for persistent pain and include the lidocaine patch 5% and other local anesthetics, capsaicin, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, clonidine, and ketamine. A bupivacaine patch (Eladur) was under development at the time of publication. Local anesthetics used for procedural pain are discussed in Chapter 28. Topical formulations containing aspirin or NSAIDs are discussed in Chapter 7. A list of topical agents can be found in Table 24-1. The topical lidocaine patch 5% (Lidoderm) is 10 cm by 14 cm and contains 700 mg of lidocaine in an aqueous base. After removing a polyethylene terephthalate film release liner, the patch is placed directly over or adjacent to the painful area (Pasero, 2003b) (see Box 24-1 for guidelines on the use of the lidocaine patch 5%). The patch is not sterile so should not be placed in wounds, but they are often placed around painful wounds. They may be cut to fit smaller areas as well. For example, a patch can be cut into strips and wrapped around painful fingers or toes. A trial period of three weeks is recommended to determine effectiveness of lidocaine patch 5% (Dworkin, O’Connor, Backonja, et al., 2007). Lidocaine and other local anesthetics relieve pain primarily by suppressing the activity of peripheral sodium channels thereby reducing ectopic, paroxysmal discharges and pathologic pain transmission (see Section I and Figure I-2 on pp. 4-5). A major advantage of analgesics such as the lidocaine patch 5% is that they work peripherally rather than systemically, and thus are associated with a low incidence of systemic adverse effects (Stanos, 2007). Although lidocaine is a local anesthetic, penetration of the drug following topical application is sufficient to produce an analgesic effect but not a sensory block. Patients should be told to expect pain relief, not anesthesia. At this time, the lidocaine patch 5% is available only by prescription. (See lidocaine patch 5% patient medication information, Form V-8 on pp. 773-774, at the end of Section V.) • Postherpetic neuralgia (Argoff, 2000; Argoff, Galer, Jensen et al., 2004; Dubinsky, Kabbani, El-Chami, et al., 2004; Dworkin, Schmader, 2003; Gammaitoni, Alvarez, Galer, 2003; Galer, Rowbotham, Perander, 1999; Katz, Gammaitoni, Davis, et al., 2002; Khaliq, Alam, Puri, 2007; Pasero, 2003b; Rowbotham, Davies, Verkempinck et al., 1996) • Acute herpes zoster (within 4 weeks of infection onset) (Lin, Fan, Huang, et al., 2008) • Variety of other focal peripheral neuropathic pain syndromes (see list in Meier, Wasner, Faust, et al., 2003) • Painful diabetic neuropathy (Argoff, Backonja, Belgrade, et al., 2006; Argoff, Galer, Jensen, et al., 2004; Barbano, Herrmann, Hart-Gouleau, et al., 2004; Devers, Galer, 2000; Veves, Backonja, Malik, 2008) • Idiopathic distal sensory polyneuropathy (Hermann, Barbano, Hart-Gouleau et al., 2005) • Myofascial pain (Argoff, 2002; Dalpiaz, Dodds, 2002; Gammaitoni, Alvarez, Galer, 2003) • Neuroma (Devers, Galer, 2000) • Meralgia paresthetica (Devers, Galer, 2000) • Intercostal neuralgia (Devers, Galer, 2000) • Traumatic rib fracture (Ingalls, Horton, Bettendorf, et al., 2009) • Erythromelalgia (Davis, Sandroni, 2002) • Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS types 1 and 2) (Devers, Galer, 2000) • Cervical pain (Gammaitoni, Alvarez, Galer, 2003) • Back pain (Gammaitoni, Alvarez, Galer, 2003; Gimbel, Linn, Hale, et al., 2005; Hines, Keaney, Moskowitz, et al., 2002) • Radiculopathy (Devers, Galer, 2000) • Variety of persistent pains (head, neck, extremity, back, knee) (Fishbain, Lewis, Cole, et al., 2006) • Cancer-related neuropathic pain (Wilhelm, Griessinger, Koppert, et al., 2005) • Osteoarthritis (OA) (Gammaitoni, Galer, Onawola, et al., 2004) • Carpal tunnel syndrome (Nalamachu, Crockett, Gammaitoni, et al., 2006) • Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (postoperative pain) (Saber, Elgamal, Rao, et al., 2008) • Radical retropubic prostatectomy (Habib, Polascik, Weizer, et al., 2009) • Inguinal hernia repair (Lockhart, 2006) • Persistent neuropathic postsurgical pain (thoracotomy, mastectomy) (Devers, Galer, 2000)

Topical Analgesics for Persistent (Chronic) Pain

Lidocaine Patch 5%

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree