Table 4.1 Thyroiditis Classification by Inflammatory Response and Clinical Course | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are usually elevated.62 A minority of patients have significant elevation of antibodies to thyroglobulin (Tg) or thyroperoxidase (TPO), but these elevated titers are usually transient.58,59,63,64,65

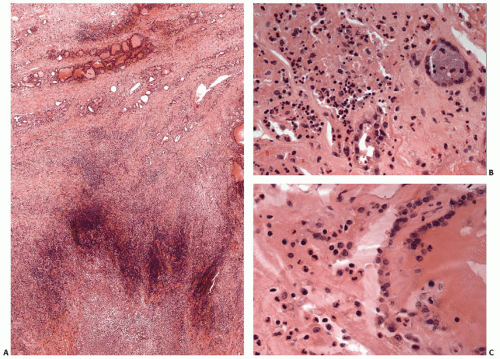

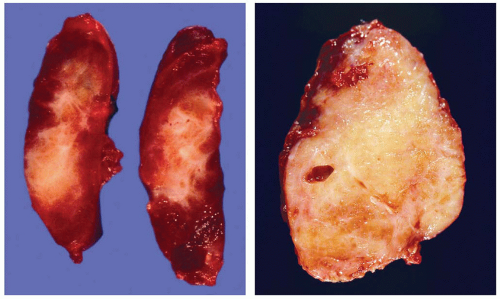

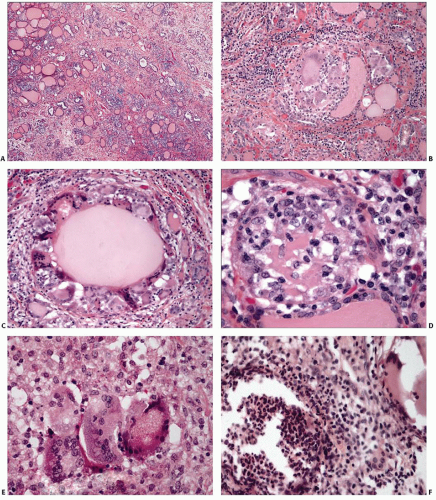

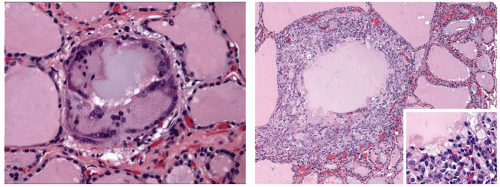

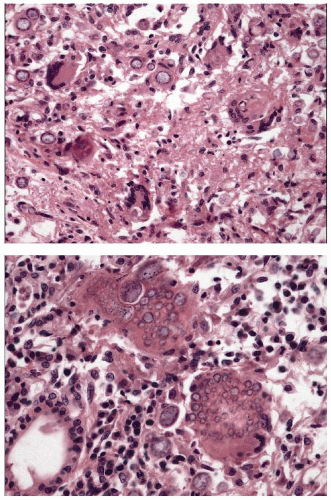

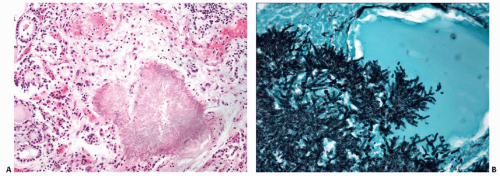

degenerated follicular cells.82,83,87 Oncocytic follicular cells are absent. In the latter stages, characteristic findings include multinucleated giant cells, strands of fibrous tissue, and a mixture of lymphocytes, macrophages, and possibly neutrophils.88,89,90 Follicular cells are usually scant to absent, and granulomata are rarely seen.

diseases has been observed.110,111,112,113,114 The most frequent coexisting disease is chronic lymphocytic (Hashimoto) thyroiditis. Although several cases of sarcoidosis with clinically overt chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis are relatively low, the incidence seems higher than by simple coincidence. The frequency of autoantibodies to Tg and/or TPO among individuals with sarcoidosis has been found to be as high114 as 27%. Rare cases of sarcoidosis associated with hyperthyroidism have also been reported.113,115,116,117

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree