I. NORMAL ANATOMY. The thyroid gland is a bilobed organ in the lower neck surrounding, and in intimate contact with, the trachea. It consists of right and left lobes connected by a small isthmus in the midline (Fig. 24.1). Two functioning cell types, follicular cells and C (calcitonin) cells, comprise the thyroid follicle. The follicular component develops from invaginating tissue from the tongue base (foramen cecum) at 5 to 6 weeks gestation. Through differential embryonic growth and migration, the bilobed gland assumes its definitive location in the neck, and the thyroglossal duct, the structure along the path of its downward migration, undergoes atrophy. The C-cells, which comprise 0.1% or less of the total thyroid cell mass, originate from the ultimobranchial body that develops from the fourth branchial pouches; they are distributed in a density gradient, being most prominent in the upper lobes.

The normal gland has a relatively firm consistency, is light brown, and lacks any obvious nodules. Microscopically, it consists of follicles lined by low cuboidal bland epithelial cells. This follicular epithelium surrounds a central core of eosinophilic colloid. In normal glands, the follicles are relatively consistent and regular in size (e-Fig. 24.1).* The C-cells lie within the follicular epithelium and are invested by the basement membrane. They are inconspicuous in normal thyroid.

II. GROSS EXAMINATION, TISSUE SAMPLING, AND HISTOLOGIC SLIDE PREPARATION

A. Biopsy. Tissue needle biopsies of the thyroid gland are only very rarely performed because fine needle aspiration is technically easy to perform, has low morbidity, and is effective for triaging lesions for further management (see the section on Cytopathology).

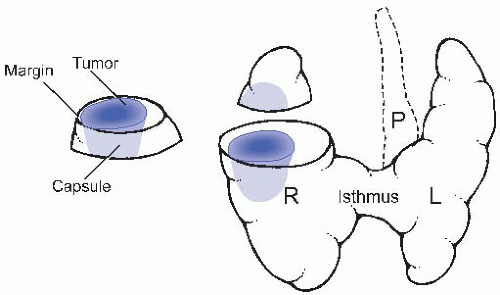

B. Resection. Hemithyroidectomy and total thyroidectomy are common procedures for management of thyroid disease. The specimens from both types of procedure are handled in a similar manner. The gland is oriented, if possible, on the basis of the anatomy alone or on markings provided by the surgeon. It is then measured and weighed. The surface is inspected for any disruptions or attached soft tissue. Small nodules of tissue situated in the adjacent tissues may represent lymph nodes, parathyroid glands, or sequestered thyroid in cases of nodular hyperplasia. The gland should be inked, sectioned in an axial plane (bread loafed) at intervals of 3 to 5 mm, and described, clearly indicating masses and their size(s), color, and consistency. For diffuse or inflammatory lesions, three

or four sections from each lobe should be submitted for microscopic examination, along with one of the isthmus. For a solitary, encapsulated mass, the entire circumference of the capsule should be sampled, including the surrounding thyroid tissue because the distinction of adenoma from carcinoma relies on features seen in the capsule. For a solitary, nonencapsulated or not completely encapsulated mass, at least one section per centimeter should be submitted, and some sections should demonstrate the closest inked margin (Fig. 24.1). For multinodular glands (nodular hyperplasia), sections of each major nodule should be submitted, including the edge and/or adjacent soft tissue margin. Any attached perithyroidal soft tissue should be removed and sampled. Any lymph nodes or parathyroid glands should be removed and sampled as well, although oftentimes, the parathyroid gland(s) are first detected by microscopic examination (the number of parathyroid glands should be recorded in one of the final diagnostic lines to highlight their presence).

Prophylactic thyroidectomy is currently recommended in infancy, early childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood for patients with a germline RET gene mutation. The gross specimen often consists of the thyroid gland with no grossly identifiable lesions. Each lobe should be entirely submitted sequentially from superior to inferior to allow thorough examination for C-cell hyperplasia or medullary microcarcinoma.

III. DIAGNOSTIC FEATURES OF COMMON DISEASES

A. Developmental. Residual thyroid tissue can be present anywhere along the path of thyroid migration during development. Carcinomas can rarely develop outside of the thyroid gland in these residual tissue sites.

1. Pyramidal lobe. The most common development remnant is a pyramidal lobe, a linear projection of thyroid tissue from the isthmus pointing cranially (Fig. 24.1).

2. Thyroglossal duct cyst. Failure of closure of the thyroglossal duct commonly results in a midline cyst known as a thyroglossal duct cyst (TDC). Excision specimens generally consist of several nondescript fragments of tissue, and a visible cyst is not always appreciated. Because remnants of the midline tract pass through the hyoid bone, the latter should be identified. Failure to resect the bone often results in persistence of the TDC. If a cyst is identified grossly, it should be sampled in a few sections to document the type of epithelial lining, which is often obscured by acute inflammation. Because TDCs develop from a hollow tube, not all of them have thyroid tissue in their walls (only ˜5%

do on routine sections, and only about 40% do even on serial sectioning). Otherwise, microscopically, these lesions have a squamous or respiratorytype lining epithelium without a muscular wall (e-Fig. 24.2). TDCs can get infected and inflamed with associated granulation tissue.

3. Lingual thyroid. Thyroid tissue can be present at the base of the tongue at the site of developmental invagination, referred to as lingual thyroid. Microscopically, the thyroid tissue is normal.

B. Inflammation (thyroiditis)

1. Acute thyroiditis is caused predominantly by bacteria but rarely can have a fungal origin. It is usually seen in the setting of neck trauma or as spread from infection of adjacent structures. Microscopically, the gland is infiltrated by neutrophils with microabscesses and necrotic foci. Organisms can often be seen with or without special stains. Patients usually recover with antibiotics.

2. Subacute thyroiditis: de Quervain thyroiditis. Technically referred to as granulomatous thyroiditis or subacute thyroiditis, de Quervain thyroiditis is a disease primarily of women and is thought to be due to systemic viral infection. There is linkage to HLA type Bw35. Patients present with fever, malaise, and neck pain. The disease consists of three phases: hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and recovery.

Grossly, the gland is usually asymmetrically enlarged and slightly firm. Microscopically, in the hyperthyroid phase, there is disruption of the follicles, with depletion of colloid and associated acute inflammation with microabscesses. Aggregates of neutrophils in the follicles are a characteristic feature. Multinucleated giant cells are rare. In the hypothyroid phase, the follicular epithelium may be very scarce, and there is a florid mixed inflammatory response with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells. Finally, in recovery, there is regeneration of follicles with fibrosis. Virtually all patients recover thyroid function after a few months without specific treatment.

3. Chronic thyroiditis

a. Focal lymphocytic thyroiditis. Also termed nonspecific thyroiditis or focal autoimmune thyroiditis, this is a common disorder usually discovered incidentally in surgically excised thyroids, and is found in 25% to 60% of patients in autopsy studies, and is most common in older women. Patients are asymptomatic but often have a low level of antithyroid antibodies.

There are no significant gross findings. Microscopically, focal lymphocytic thyroiditis consists of aggregates of lymphocytes, occasionally with germinal centers, between the follicles (e-Fig. 24.3). The lymphocytes can infiltrate follicles, but there is no significant destruction or damage. The disease is not progressive.

b. Hashimoto thyroiditis. Hashimoto thyroiditis, or chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, is an autoimmune disease with thyroid enlargement and circulating antithyroid antibodies. It occurs most often in middle-aged women and is caused by autoantibodies against thyroglobulin (Tg) and thyroid peroxidase (TPO) that lead to inflammation and destruction of the follicles. There is a familial association, and Hashimoto thyroiditis is often associated with other autoimmune diseases. There is also an association with HLA types DR3 and DR5. Patients can present with a hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism and are typically in their sixth decade. Ultrasound shows an enlarged gland with a hypoechogenic pattern, and anti-Tg and anti-TPO antibodies are present in approximately 60% and 95% of cases, respectively.

Grossly, the thyroid is diffusely enlarged and firm with a mildly nodular surface. On sectioning, lobulation is accentuated due to fibrosis, and the gland is tan-yellow or off-white rather than the usual brown due to

the abundant lymphoid tissue. Microscopically, there are sheets of lymphocytes and plasma cells with abundant germinal centers. Florid inflammation often renders the residual follicles and follicular epithelium inconspicuous. The follicles are atrophic with minimal colloid. Characteristic Hürthle cell change is present, consisting of large cells with abundant, granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm and large, round nuclei with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli (e-Fig. 24.4). The inflammatory infiltrate may extend into the perithyroidal soft tissue causing adherence of the gland at the time of surgery. Finally, there may be fibrous septa between the lobules, and the follicular epithelium may develop squamous metaplasia.

A number of variants of Hashimoto thyroiditis occur, including fibrous (sclerosing), fibrous atrophy, juvenile, and cystic forms. Both of the fibrous variants show the same histologic findings, namely retention of a lobulated pattern with extensive and severe fibrosis. Atrophic follicular cells are more scattered but show Hürthle cell change, and there is abundant chronic inflammation with germinal centers. In the fibrous variant, the gland is markedly enlarged throughout. In the fibrous atrophy variant, the gland is small and shrunken. Both of the latter variant forms are associated with marked hypothyroidism and high titers of antithyroid antibodies.

The differential diagnosis for Hashimoto thyroiditis includes Riedel thyroiditis and lymphoma. The fibrous variant of Hashimoto thyroiditis may simulate Riedel thyroiditis with an enlarged fibrotic gland. However, the fibrosis is typically limited to the gland itself, whereas in Riedel thyroiditis there is severe adherence of the fibrotic gland to the neck soft tissues. The dense inflammation in Hashimoto thyroiditis can simulate lymphoma, and most thyroid lymphomas do arise in the setting of Hashimoto thyroiditis. The distinction lies in the absence of sheets of atypical lymphocytes, the lack of a strikingly prominent lymphoepithelial pattern, and the lack of clonality of the lymphocytes by flow cytometry or molecular studies.

The issue of whether there is an increased risk of papillary carcinoma in Hashimoto thyroiditis is a controversial topic. Whether this is the case or not, the nuclear features of the epithelium can simulate those of papillary carcinoma (including nuclear crowding, clear chromatin, and occasional nuclear grooves) and develop frequently in the inflamed follicular epithelium. A true carcinoma arising in Hashimoto thyroiditis should stand out sharply from the neighboring follicular epithelium, as in uninflamed thyroid.

c. Graves disease. Graves disease is also known as diffuse hyperplasia and is an autoimmune condition resulting in excess thyroid hormone production. It causes the majority of cases of spontaneous hyperthyroidism, occurs most often in the third and fourth decades, and is 5 to 10 times more common in women. Thyroid-specific autoantibodies, specifically thyroidstimulating immunoglobulin (TSI), are present in Graves disease patients. TSI binds to and stimulates thyrocytes through the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor, resulting in thyrotoxicosis. Patients also develop a characteristic infiltrative ophthalmopathy with proptosis.

Grossly, the thyroid gland is diffusely and symmetrically enlarged. Posttreatment or after long-standing disease, the gland may be somewhat nodular or fibrotic. Microscopically, the gland typically shows a low-power lobular accentuation due to increased septal fibrous tissue. Inflammation varies from none, to patchy lymphocytic, to lymphocytic with formation of germinal centers. The follicular epithelium has increased amounts of cytoplasm, is convoluted and irregular, and often assumes an almost papillary appearance. Colloid is decreased or absent and typically

has a “scalloped” appearance from clearing at the interface with the follicular epithelium (e-Figs. 24.5 and 24.6). Treated cases have a variable morphology and often have cellular nodules mimicking adenomas. After radioactive iodine treatment, there can be marked nuclear atypia. The differential diagnosis includes papillary carcinoma when the stellate outlines of follicles resemble papillae. The lack of cytologic changes of papillary carcinoma and the diffuse gland involvement are keys to the correct diagnosis of Graves disease.

d. Riedel thyroiditis. A peculiar form of fibrosing disease, Riedel thyroiditis is a chronic thyroiditis of unknown etiology which is more common in women, occurs most commonly in the fifth decade, and is commonly associated with fibrosing disease at other sites such as the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, and lung. Patients present with firm thyroid enlargement and local symptoms such as dysphagia, stridor, or dyspnea. Recurrent laryngeal nerve or sympathetic trunk involvement can lead to hoarseness or Horner syndrome; compression of the large vessels can lead to superior vena cava syndrome. Most patients are euthyroid at presentation, but many subsequently develop hypothyroidism.

Grossly, the thyroid gland is usually received in irregular pieces because the fibrosis makes it difficult to remove surgically. It is tan to white, firm, and may have attached muscle. Microscopically, the characteristic finding is dense and hypocellular eosinophilic fibrous tissue with scattered and patchy aggregates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils, without germinal centers or granulomas. Rare entrapped and atrophic thyroid follicles are seen without Hürthle cell change. A characteristic finding is small veins with infiltrating lymphocytes and myxoid intimal thickening (features of occlusive vasculitis). Marked fibrosis extends into and involves the surrounding soft tissue as well.

The differential diagnosis includes hypocellular anaplastic thyroid carcinoma and fibrous or sclerosing Hashimoto thyroiditis. The lack of necrosis or markedly atypical cells rules out anaplastic carcinoma. The lack of Hürthle cell change and germinal centers, and the profound degree of perithyroidal fibrosis, rules out fibrous Hashimoto disease.

C. Nodular hyperplasia. Nodular hyperplasia (clinically termed multinodular goiter) is an extremely common disorder of the thyroid gland. It is the enlargement of the gland with varying degrees of nodularity. The pathogenesis is complex but has been classically related to iodine deficiency with impaired thyroid hormone synthesis and subsequent TSH stimulation. With supplementation of iodine in the diet, nodular hyperplasia has also been related either to excess iodine intake with impaired organification or to genetic factors. It is much more common in women than men and typically presents in middle age as asymptomatic enlargement. Large goiters, however, can cause dysphagia, hoarseness, or stridor and can extend into the upper mediastinum. A small percentage of patients present with hyperthyroidism (toxic multinodular goiter).

Grossly, the thyroid gland is diffusely but irregularly enlarged. Some glands can attain a weight of several hundred grams. Parasitic nodules that have only a tenuous connection to the gland can develop. On sectioning, the nodules may be semitranslucent, glistening, fleshy, red-brown, tan, and solid or, more commonly, show varying degrees of degeneration with cystic change, hemorrhage, fibrosis, and calcification. Heterogeneity of the nodules is typical (e-Fig. 24.7).

Microscopically, nodular hyperplasia is also heterogeneous. The common appearance is nodules composed of variably sized follicles (e-Fig. 24.8). The nodules may be quite cellular with tightly packed follicular epithelium and little colloid, resembling follicular adenomas or carcinomas. Around cystic areas there is often fibrosis with variably sized foci of dystrophic calcification and

hemorrhage, with abundant hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Hürthle cell change is common. Pseudopapillary and truly papillary structures (Sanderson polsters) can project into the cystic areas. The surrounding grossly normal thyroid tissue usually demonstrates microscopic nodularity as well.

TABLE 24.1 WHO Histological Classification of Thyroid Tumors

Thyroid carcinomas

Papillary carcinoma

Follicular carcinoma

Poorly differentiated carcinoma

Undifferentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia

Mucinous carcinoma

Medullary carcinoma

Mixed medullary and follicular carcinoma

Spindle cell tumor with thymus-like differentiation

Carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation

Thyroid adenoma and related tumors

Follicular adenoma

Hyalinizing trabecular tumor

Other thyroid tumors

Teratoma

Primary lymphoma and plasmacytoma

Ectopic thymoma

Angiosarcoma

Smooth muscle tumors

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors

Paraganglioma

Solitary fibrous tumor

Follicular dendritic cell tumor

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Secondary tumors

From: DeLellis RA, Lloyd RV, Heitz P, et al., eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics. Tumours of Endocrine Organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004. Used with permission.

The differential diagnosis for cellular nodules includes follicular adenoma or carcinoma. Hyperplastic nodules have a fibrous capsule that is not as well developed or continuous as the capsule of adenomas and carcinomas. Follicular adenomas are discrete and well-encapsulated lesions, are microscopically different from the surrounding thyroid tissue, do not show cystic change or degeneration, and have a monotonous cell population—all features that are not characteristic of hyperplastic nodules. Papillary areas in nodular hyperplasia show basally oriented nuclei without the crowding or other features of papillary carcinoma.

D. Neoplasms. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the thyroid gland is listed in Table 24.1.

1. Adenoma. Follicular adenomas are benign, encapsulated tumors that are clonal. They are seen mostly in young to middle-aged adults and are more common in women than men. There is a relationship with previous irradiation or radiation exposure, just as with follicular carcinoma. There is also an association with inherited diseases including Cowden disease and Carney

complex. Most follicular adenomas are asymptomatic and are detected by careful physical examination or incidentally by imaging performed for other reasons.

TABLE 24.2 Histologic Features Differentiating the Solitary Benign from the Malignant Follicular Lesion

Benign

Malignant

Complete but delicate capsule

Dense, circumferential fibrosis

Entrapped or sequestered thyroid in/near capsule

Transcapsular “mushrooming” invasion

Juxtaposed or prolapsed thyroid tissue near vessels, but with intact endothelium

Adherence of thyroid tissue to endothelium with associated thrombus

Grossly, follicular adenomas are very well-defined, round to oval lesions with a complete capsule. They are typically very soft and homogeneous with a color ranging from gray-white to tan or dark brown depending on the amount of colloid (e-Fig. 24.9). Cystic change and hemorrhage are uncommon. Microscopically, they are encapsulated without, by definition, capsular or vascular invasion. They show a monotonous follicular or trabecular arrangement. The microfollicular pattern features trabeculae with only scattered small follicles with colloid. The macrofollicular pattern has prominent, large follicles with abundant colloid. The cells typically have small amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm and are quite regular with uniform, round nuclei with condensed chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli. There is a well developed and moderately thick capsule (e-Fig. 24.10). As with all endocrine organ tumors, there may be a marked degree of nuclear pleomorphism which is not necessarily an indication of malignancy or aggressive behavior. Mitotic figures are rare.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thyroid

Thyroid

Changqing Ma

James S. Lewis Jr.

Rebecca D. Chernock