Chapter 3 Therapeutic modalities

Introduction

As discussed in Chapter 2, the desired effect of any therapeutic intervention is to improve symptoms or prognosis or both. From a pathological point of view, therapeutic interventions may be directed at disease prevention, alleviation of the effects of existing disease, or permanent cure (i.e. restoration to a state of function and prognosis equivalent to those of a healthy individual of the same age, without the need for continuing therapeutic intervention). In practice, there are relatively few truly curative interventions, and they are mainly confined to certain surgical procedures (e.g. removal of circumscribed tumours, fixing of broken bones) and chemotherapy of some infectious and malignant disorders. Most therapeutic interventions aim to alleviate symptoms and/or improve prognosis, and there is increasing emphasis on disease prevention as an objective.

• Advice and counselling (e.g. genetic counselling)

• Psychological treatments (e.g. cognitive therapies for anxiety disorders, depression, etc.)

• Dietary and nutritional treatments (e.g. gluten-free diets for coeliac disease, diabetic diets, etc.)

• Physical treatments, including surgery, radiotherapy

• Pharmacological treatments – encompassing the whole of conventional drug therapy

• Biological and biopharmaceutical treatments, a broad category including vaccination, transplantation, blood transfusion, biopharmaceuticals (see Chapters 12 and 13), in vitro fertilization, etc.

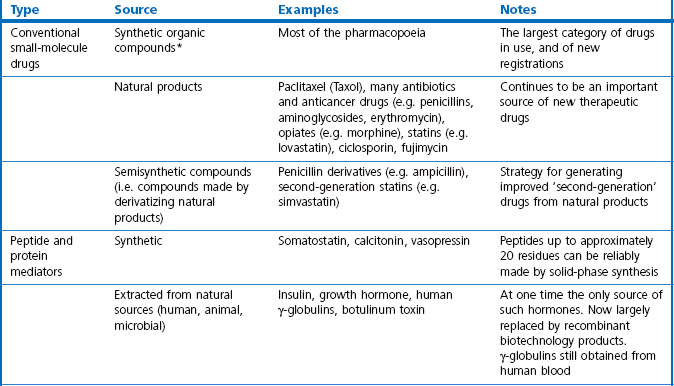

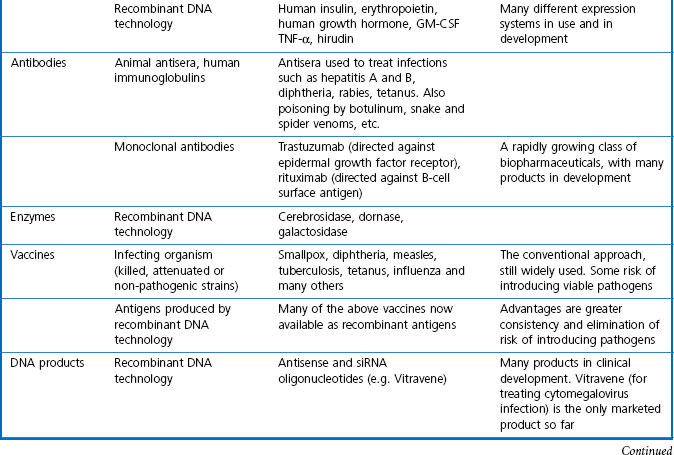

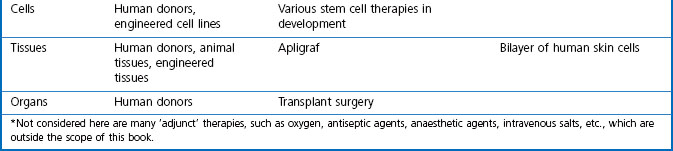

In this book we are concerned with the last two treatment categories on the list, summarized in Table 3.1, and in this chapter we consider the current status and future prospects of the three main fields; namely, ‘conventional’ therapeutic drugs, biopharmaceuticals and various biological therapies.

Conventional therapeutic drugs

Small-molecule drugs, either synthetic compounds or natural products, have for a long time been the mainstay of therapeutics and are likely to remain so, despite the rapid growth of biopharmaceuticals in recent years. For their advantages and disadvantages see Box 3.1.

Box 3.1

Advantages and disadvantages of small-molecule drugs

• ‘Chemical space’ is so vast that synthetic chemicals, according to many experts, have the potential to bind specifically to any chosen biological target: the right molecule exists; it is just a matter of finding it.

• Doctors and patients are thoroughly familiar with conventional drugs as medicines, and the many different routes of administration that are available. Clinical pharmacology in its broadest sense has become part of the knowledge base of every practising doctor, and indeed, part of everyday culture. Although sections of the public may remain suspicious of drugs, there are few who will refuse to use them when the need arises.

• Oral administration is often possible, as well as other routes where appropriate.

• From the industry perspective, small-molecule drugs make up more than three-quarters of new products registered over the past decade. Pharmaceutical companies have long experience in developing, registering, producing, packaging and marketing such products.

• Therapeutic peptides are generally straightforward to design (as Nature has done the job), and are usually non-toxic.

• As emphasized elsewhere in this book, the flow of new small-molecule drugs seems to be diminishing, despite increasing R&D expenditure.

• Side effects and toxicity remain a serious and unpredictable problem, causing failures in late development, or even after registration. One reason for this is that the selectivity of drug molecules with respect to biological targets is by no means perfect, and is in general less good than with biopharmaceuticals.

• Humans and other animals have highly developed mechanisms for eliminating foreign molecules, so drug design often has to contend with pharmacokinetic problems.

• Oral absorption is poor for many compounds. Peptides cannot be given orally.

Although the pre-eminent role of conventional small-molecule drugs may decline as biopharmaceutical products grow in importance, few doubt that they will continue to play a major role in medical treatment. New technologies described in Section 2, particularly automated chemistry, high-throughput screening and genomic approaches to target identification, have already brought about an acceleration of drug discovery, the fruits of which are only just beginning to appear. There are also high expectations that more sophisticated drug delivery systems (see Chapter 16) will allow drugs to act much more selectively where they are needed, and thus reduce the burden of side effects.

Biopharmaceuticals

For the purposes of this book, biopharmaceuticals are therapeutic protein or nucleic acid preparations made by techniques involving recombinant DNA technology (Walsh, 2003), although smaller nucleotide assemblies are now being made using a chemical approach. Although proteins such as insulin and growth hormone, extracted from human or animal tissues, have long been used therapeutically, the era of biopharmaceuticals began in 1982 with the development by Eli Lilly of recombinant human insulin (Humulin), made by genetically engineered Escherichia coli. Recombinant human growth hormone (also produced in E. coli), erythropoietin (Epogen) and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) made by engineered mammalian cells followed during the 1980s. This was the birth of the biopharmaceutical industry, and since then new bioengineered proteins have contributed an increasing proportion of new medicines to be registered (see Table 3.1 for some examples, and Chapters 12 and 22 for more details). The scope of protein biopharmaceuticals includes copies of endogenous mediators, blood clotting factors, enzyme preparations and monoclonal antibodies, as well as vaccines. See Box 3.2 for their advantages and disadvantages. This field has now matured to the point that we are now facing the prospect of biosimilars consequent on the expiry of the first set of important patents in 2004 and notwithstanding the difficulty of defining ‘difference’ in the biologicals space (Covic and Kuhlmann 2007).

Box 3.2

Advantages and disadvantages of biopharmaceuticals

• The main benefit offered by biopharmaceutical products is that they open up the scope of protein therapeutics, which was previously limited to proteins that could be extracted from animal or human sources.

• The discovery process for new biopharmaceuticals is often quicker and more straightforward than with synthetic compounds, as screening and lead optimization are not required.

• Unexpected toxicity is less common than with synthetic molecules.

• The risk of immune responses to non-human proteins – a problem with porcine or bovine insulins – is avoided by expressing the human sequence.

• The risk of transmitting virus or prion infections is avoided.

• Producing biopharmaceuticals on a commercial scale is expensive, requiring complex purification and quality control procedures.

• The products are not orally active and often have short plasma half-lives, so special delivery systems may be required, adding further to costs. Like other proteins, biopharmaceutical products do not cross the blood–brain barrier.

• For the above reasons, development generally costs more and takes longer, than it does for synthetic drugs.

• Many biopharmaceuticals are species specific in their effects, making tests of efficacy in animal models difficult or impossible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree