WEB ADDRESSES

• American Botanical Council: http://www.herbs.org/

• U.S. Pharmacopeia: http://www.usp.org

• Food and Drug Administration (FDA): http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov

REFERENCES

1. German Commission E Monographs. Austin, TX: American Botanical Council; 1998.

2. Natural medicines comprehensive database. Stockton, CA: Prescriber’s letter; 2014. http://www.naturaldatabase.com. Accessed March 8, 2014.

3. DerMarderosian A. The review of natural products by facts and comparisons. St. Louis, MO: Wolters Kluwer; 1999.

4. Rotblatt M, Ziment I. Evidence-based herbal medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Hanley and Belfus; 2002.

5. Krinsky DL, LaValle JB, Hawkins EB, et al. Natural therapeutics pocket guide. 2nd ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2003.

6. Brown DJ. Herbal prescriptions for health and healing. Roseville, CA: Prima Health; 2003.

| Management of Acute and Chronic Nonmalignant Pain |

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

“The aim of the wise is not to secure pleasure, but to avoid pain.” Aristotle

Definitions

Pain is a frequent reality in the human condition and is one of the most common reasons people seek out medical attention. Chronic pain affects up to one-third of all Americans at some point in their lives. It is the leading cause of disability and has caused the loss of more than $100 billion to the U.S. economy in direct costs and lost productivity.

Pain is defined as an “unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.”1 It is also, “whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever s/he says it does.”1 These definitions convey the complex human response to pain, hint at the suffering that often accompanies it, and acknowledge the reality that some patients feel pain, yet have no objective findings or identifiable cause.

Nociception is the process by which pain from tissue or nerve damage is communicated to the central nervous system. Nociceptive pain is caused by a noxious stimulus within the context of an intact healthy nervous system, whereas neuropathic pain is caused by nervous system malfunction or damage. Often, both nociceptive and neuropathic pain coexist.

Injured tissues undergo cell breakdown and release various products and mediators of inflammation: prostaglandins, substance P, bradykinin, histamine, serotonin, and cytokines. These substances activate sensory nociceptors to generate nerve impulses and also sensitize them to increase their excitability and frequency discharge.

Nerve impulses travel from the periphery into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, and are propagated by the release of excitatory amino acids, such as glutamate and aspartate, and neuropeptides, such as substance P. Repeated stimulation activates the N-methyl d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in a process known as “wind up.” Impulses within the dorsal horn are then projected to various parts of the brain in ascending tract bundles. Pain impulses are not simply related to the brain unrestricted, however. Pain traffic is inhibited inside the dorsal horn by spinal interneurons as well as descending inhibitory input from the brain. Inhibition in both pathways occurs via the release of inhibitory amino acids such as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), endogenous opioids, serotonin, and norepinephrine.

Pain impulses are transmitted to many areas of the brain, including the cortex and the limbic system. This perception of pain involves not only the neurochemical impulse at the molecular level, but also the patient’s emotions, memories, cultural values, ethics, mental state, and previous pain experiences, making pain perception unique and individualized to each patient.

Prolonged exposure to noxious pain generating stimulation or inflammatory mediators, can lead to sensitization of the pain pathway in both the peripheral and the central nervous system. Sensitization can trigger changes in the nervous system that can persist indefinitely. This sensitization can lead to clinical pain states such as (a) hyperalgesia—an increased response to painful stimuli that can even extend beyond the region of injury, (b) allodynia—a painful response to a normally innocuous stimulus, (c) persistent pain—a prolonged pain, from minutes to hours, after a transient stimulus, and (d) referred pain—the spread of pain to uninjured tissues.

Understanding the pain pathway and sensitization has many clinical implications and allows for the direct targeting of various places in the treatment of pain.

ACUTE PAIN

Acute pain by definition is a new onset of pain, usually from an identifiable cause and with a predictable course and time of resolution. It is a “complex, unpleasant experience with emotional and cognitive, as well as, sensory features that occur in response to tissue trauma.”1 Even brief exposure to painful stimuli can cause intense suffering, neuronal remodeling, and the development of chronic pain. Therefore, aggressive treatment of acute pain may decrease the risk of these complications.

Assessment of acute pain involves taking a detailed history with attention to the mechanism of injury, if known, and the characteristics of the pain, followed by a full physical examination of the painful area. The patient should be provided analgesia as soon as possible after initial assessments have been made and relief of the pain should not be delayed while work-up is completed.

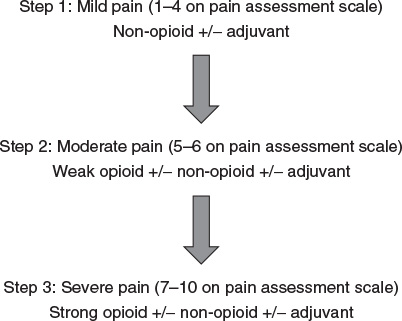

Pharmacologic treatment of acute pain can be guided by the patient’s reported numeric pain score (see Figure 22.4-1) and the World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder (see Figure 22.4-2).

For mild to moderate pain scores, non-opioids and weak opioids are indicated. These include acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), tramadol, hydrocodone, and oxycodone. Combination therapy with acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and one of the weak opioids is safe and may provide significant analgesia by targeting many areas along the pain pathway. For more severe pain, strong opioids, such as morphine, hydromorphone, and intravenous (IV) fentanyl can be used, along with the non-opioid medications. There is little use of methadone in the setting of acute pain and the potential of significant harm exists.

If clinically feasible, use oral or mucosal forms of analgesia, followed by parenteral forms, preferably IV. Intramuscular analgesia should be limited due to its inconsistent absorption, painful administration, and risk of tissue fibrosis. Those topical analgesics designed to only affect surrounding tissue, such as lidocaine, capsaicin, and EMLA cream, may be of benefit. Fentanyl patches, however, have limited use in the treatment of acute pain as they are contraindicated in the opiate-naïve patient and take up to 72 hours to achieve full analgesic dosing.

Useful adjuvants in the treatment of acute pain include muscle relaxants, heat, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and PRINCE, which refers to protection, rest, immobilization, ice, compression, and elevation. If the patient is experiencing significant neuropathic pain, usually described as a burning, stinging, “pins and needles” sensation, the addition of antiseizure medications as well as the above-mentioned topical medications may be of benefit.

If opioids are needed beyond the first few days to weeks, short-acting forms should be used initially, but can be transitioned to long-acting formulations. Patients should be counseled on the side effects of opioid therapy to include nausea, vomiting, constipation, pruritus, urinary retention, and respiratory depression, as well as the risks of driving or operating heavy machinery.

Although the benefit of aggressively treating acute pain does exist, the growing problem of opioid addiction in America, especially among the adolescent population, makes both judicious prescribing of opioids necessary as well as careful consideration to the realistic quantity of medication that needs to be dispensed. Patients should be advised to keep all medications in a safe and preferably locked area and to safely dispose of any unused medications. Patients may dispose of opioids by returning them to the pharmacy, taking them to a law enforcement facility or placing them in an inedible substance inside a sealed container in the trash. The Food and Drug Administration does allow the following opioids to be flushed down the toilet: fentanyl (including the patches), hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, and oxymorphone.

Figure 22.4-1. A numeric pain scale can assist the patient in communicating pain level in an objective manner.

Figure 22.4-2. World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder can help guide appropriate selection of pain treatment based on numeric pain assessment scores.

Finally, the depth of emotional, mental, and psychological pain that the patient may also be experiencing beyond that of the physical, needs to be identified, fully validated, and treated, if present. A multidisciplinary team approach involving law enforcement, social work, and mental health workers may be required to ensure that all aspects of the patient’s pain are addressed.

CHRONIC NONMALIGNANT PAIN

Chronic nonmalignant pain (CNMP) is pain that extends beyond the expected period of healing, usually 3 to 6 months, and is not caused by cancer. It may develop de novo with no apparent cause or there may be an identifiable level of tissue pathology, progress from an acute injury, or be caused by a chronic condition such as rheumatoid arthritis. Regardless of its etiology, CNMP often disrupts sleep and normal living; ceases to serve a protective function; and may cause vocational, social, and psychological problems.

Assessment

Assessment of CNMP requires considerable time and attention and may require longer appointments dedicated to addressing the patient’s CNMP complaints. A detailed pain history should be taken, in addition to the patient’s past medical history, and should include characteristics of the pain, all previous testing or consultations, past and present pain management treatments, and their outcomes. This may surprisingly reveal areas in the work-up and treatment of the patient’s pain complaint that are incomplete or have been neglected. All past medical records should also be reviewed and a full physical examination should be performed with careful attention to the painful area.

Additional time should be given to screening the patient for mental illness, specifically depression and anxiety, which is overrepresented in patients with CNMP compared with the general population. Measureable, objective treatment goals should be agreed upon in addition to that of eliminating the patient’s pain.

Treatment

A multidisciplinary approach should be employed in the treatment of CNMP, involving both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment of CNMP

Psychological methods in the treatment of CNMP include

1. Patient education concerning CNMP

2. Contingency management to decrease “sick role” behavior

3. Cognitive-behavioral therapy to include both cognitive restructuring and coping skills training to alter patient’s responses to pain

4. Relaxation techniques

5. Hypnosis

6. Distraction to draw attention away from the pain and to include social and recreational activities

7. Biofeedback

8. Psychotherapy

Physical methods in the treatment of CNMP include

1. Stretching

2. Exercise/reconditioning

3. Gait and posture training

4. Applied heat or cold

5. Immobilization

6. TENS

7. Nerve stimulation via implantable devices

8. Massage

9. Acupuncture

10. Chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation

Pharmacologic Treatment of CNMP

Non-opioid analgesics, as mentioned above, include acetaminophen and NSAIDs. Although acetaminophen has no anti-inflammatory effects, it is well tolerated and can be used in the elderly, but can be hepatotoxic at doses greater than 4,000 mgs per day and 2,000 mg per day in patients with liver diseases. NSAIDs should be used cautiously in elders due to their significant side effect profile to include renal toxicity, bleeding risk, increase in blood pressure, and fluid retention; however, they can be very helpful in inflammatory conditions.

Adjuvant or coanalgesics are useful drugs that can be used to disrupt the pain pathway, treat comorbid conditions associated with CNMP, such as insomnia and mental illness, and are particularly useful in the treatment of neuropathic pain. These include the antiseizure medications, the tricyclic antidepressants, the selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, muscle relaxants, lidocaine patches, and capsaicin cream. Additionally, injectable glucocorticoid steroids are an important adjuvant therapy and can be safely administered via an intra-articular or intraspinal route as well as in limited amounts via oral, IV, or IM routes.

The use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of CNMP has increased dramatically in the past decade; however, an increase in prescription opioid abuse, addiction, diversion, and overdose deaths has also occurred. In response to this, the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine released evidence-based guidelines on the use of opioids in CNMP in 2009.2 These guidelines recently received the highest ratings for evidence-based guidelines in a systematic review and critical appraisal study of 13 pain guidelines.3 It is recommended that a clinician considering the use of opioids in a patient’s treatment of CNMP follow these guidelines.4

A summary of the guidelines is as follows:

1. A trial of opioid therapy should be considered only after a complete work-up of the pain complaint has been performed, if the pain is severe to moderate, if other modalities have failed, and the benefits outweigh the potential harms. The patient should be assessed for risk of substance abuse, misuse, or addiction. Several validated tools that stratify this risk include the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP) version 1, and the revised version (SOAPP-R), the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT), and the Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, Efficacy (DIRE) instrument.

2. Before starting opioid therapy, informed consent should be obtained from the patient. The risks of long-term use of opioid therapy, to include hyperalgesia, endocrine and immune dysfunction, should be reviewed. Consideration should be given to the creation of a written management plan agreed upon by both the provider and the patient. The plan would include objective treatment goals, the need for compliance monitoring, the use of one pharmacist and one physician to provide opioid medications, and the behaviors that might lead to discontinuation of opioid treatment.

3. The initiation of opioid treatment should be on a trial basis and discontinued if the patient’s goals are not being met. There is insufficient evidence to support the use of short-acting versus long-acting opioids and whether long-acting opioids decrease the risk of addiction or abuse. It is also unknown whether as-needed dosing or scheduled around the clock dosing is better. The opioid selection and dosing should be individualized to the patient’s goals, health problems, prior exposure to opioids, and risk of opioid abuse.

4. Methadone should be used only by clinicians familiar with its risks and variable pharmacokinetics. Methadone can cause QTc prolongation in a dose-dependent fashion or if used with other drugs known to prolong the QTc as well. Its metabolism is highly variable between individuals and can be enhanced or inhibited by other medications competing for the same enzymatic pathways. The very long half-life, as high as 120 hours in some patients, exceeds that of its analgesic effects; therefore, it should be started at no more than 1 to 2.5 mg every 8 to 12 hours, and not increased for 5 to 7 days. Lower amounts and daily dosing may also be indicated. Accordingly, methadone is not recommended for use in breakthrough pain or as an as-needed medication. When converting patients to methadone, several equianalgesic algorithms exist and insufficient evidence exists to support one over another; however, starting doses should not exceed 30 to 40 mg per day, regardless of the calculated conversion dose.

5. Monitoring of patients on opioid treatment should occur at a frequency and to the degree warranted by their risk for opioid abuse, misuse, or diversion. Monitoring should include an assessment of pain severity, progress toward treatment goals, evidence of medication compliance in the form of urine drug screens and pill counts, and the presence of adverse effects. Use of tools such as the Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool (PADT) and the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM), as well as reports from state prescription drug-monitoring programs may be helpful.

6. Opioid treatment may be used in patients with a history of drug abuse, psychiatric problems, or serious aberrant drug-related behaviors, only if the clinician can implement stringent and frequent monitoring measures. If patients are unable to comply or develop opioid addiction, referral to a structured opioid agonist treatment program with methadone or buprenorphine or to mental health and addiction specialists may be warranted.

7. Caution should be used in patients requiring repeated dose escalations and reevaluation of potential causes, to include misuse and abuse, should be performed. The benefit of exceeding >200 mg daily of morphine equivalents may not exceed the risks of adverse effects. Opioid rotation can be considered and equianalgesic dosing can be calculated. Because of incomplete cross tolerance and individual variation, the calculated initial equianalgesic dose should be reduced by 25% to 50%. Clinicians should taper or wean patients off of opioids who show no benefit from therapy, develop adverse effects, or display behaviors of misuse or abuse. In order to avoid the unpleasant, although not life-threatening symptoms of withdrawal, a slow taper of 10% dose reduction per week can be used. In some circumstances, a faster reduction of 25% to 50% every few days or referral to a structured detoxification program may be beneficial.

8. Clinicians should anticipate and treat opioid-induced adverse effects. Most side effects will resolve with time, except for constipation; thus, a bowel regimen should be instituted. Long-term use of sustained-release opioids has been associated with hypogonadism.5 Patients reporting fatigue, decreased libido, sexual dysfunction, menstrual irregularities or who are found to have osteoporosis, should be tested and treated for hormonal deficiencies. Respiratory depression can occur in patients with sleep apnea, pulmonary disorders, excessive doses of or rapid titration of initial opioid therapy or the concurrent use of opioids and other depressive substances, such as alcohol or benzodiazepines.

9. Opioid therapy should not be used as the sole means of analgesia in CNMP, but is likely to be most effective if used in conjunction with psychotherapeutic interventions, such as cognitive–behavioral therapy, functional restoration, interdisciplinary therapy, and other adjunctive non-opioid therapies.

10. Opioids can impair driving and work safety and patients should be counseled not to drive or engage in dangerous activities if they are demonstrating signs of impairment, starting opioid therapy, increasing the dose or rotating to a new opioid, taking other sedating medications, drinking alcohol, or using illegal substances.

11. Patients on opioid therapy should have a medical home and should be referred to pain specialists if additional skills or procedures are needed.

12. All patients on around the clock opioid therapy should have a plan in place for the treatment of breakthrough pain. There is insufficient evidence to suggest the optimum method for the treatment of breakthrough pain. Options include nonpharmacologic and non-opioid therapies or the addition of a short- or rapid-acting opioid, dosed at 10% to 20% of the patient’s total daily opioid dose. The risks and benefits of the addition of an opioid for breakthrough pain should be considered in light of the patient’s risk of opioid misuse or abuse.

13. Opioids should not be used in pregnancy, unless substantial benefit outweighs the risks, due to the potential adverse effects to the newborn found to be associated with maternal opioid use. These include neonatal abstinence syndrome, low birth weight, premature birth, hypoxic–ischemic brain injury, and neonatal death.

14. Clinicians should understand the federal and state guidelines, policies, and laws concerning their responsibilities when prescribing opioids in CNMP.

REFERENCES

1. Berry PH, Chapman CR, Covington EC, et al., eds. Pain: current understanding of assessment, management, and treatments. National Pharmaceutical Council, Inc. and Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Monograph. December, 2001. http://www.npcnow.org/publication/pain-current-understanding-assessment-management-and-treatments. Accessed March 30, 2014.

2. Chou R, Fanciullo G, Fine P, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain 2009;10(2):113–130.

3. Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:38–47.

4. Huntzinger A. Guidelines for the use of opioid therapy in patients with chronic noncancer pain. Am Fam Physician 2009;80(11):1315–1318.

5. Katz N, Mazer NA. The impact of opioids on the endocrine system. Clin J Pain 2009;25(20):170–175.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Everybody dies. The aim of end-of-life care is to make life’s last transition as comfortable and meaningful as possible for dying patients and their families. Death is not failure; not caring properly for dying patients is failure. Many aspects of end-of-life care planning apply to everyone, but especially to geriatric patients and to patients with life-limiting diseases. Similarly, certain aspects of end-of-life symptom and problem management apply to patients who are severely ill but are not yet considered terminally ill.

COMMUNICATION AND PLANNING ISSUES

• Break bad news in a quiet, unhurried, comfortable setting. Find out what patients know, and how much they want to know, before delivering information in a sensitive but straightforward manner, using clear language. Check for patient’s understanding and emotional response. Schedule follow-up.

• The goals of care for end-of-life patients and their families are to maximize comfort and function and to minimize pain and suffering. Achieving these goals relies on effective communication and planning.

• After assessing patient’s understanding of their clinical situation, discuss expectations and the goals of care directly with those who have decision-making capacity (see below). When possible, patients should be empowered to control their own treatment and to resolve conflicts among competing goals of care (see below). Ask patients if and how they might wish to share decision making for difficult and complex issues.

• After obtaining the patient’s permission, assess the family’s understanding of the clinical situation and discuss expectations and treatment goals with them as well. Ask patients if they need help talking to their family about their condition and clinical decisions. When meeting with families—unless otherwise directed by the patient (or by a legally appointed surrogate; see below)—try to involve all those present, probe for questions, clarify misunderstandings gently, and plan for follow-up.

• Be sensitive to cultural differences in end-of-life care values and practices. Encourage patients and families to consider community resources and pastoral care. Be aware of how your own social, moral, and religious values influence life-and-death decision making with your patients.

• “Be there.” All patients and families experience a wide range of emotions during the dying process. Anger, denial, depression, and bargaining are typical reactions. In addition, personal psychosocial problems, interpersonal family relationships, and the time line of the death (whether chronic or acute) all influence how patients and families react. The family physician’s continued presence and validation of these reactions—even when other medical specialists are involved in patient management—may be therapeutic for everyone.

• Ethical planning issues. Addressing patients’ desires about end-of-life care and life-sustaining treatment should be part of health care maintenance performed during regular office visits. Normalize this “informed consent” for the future by making such statements as, “I discuss life-sustaining treatments and advance directives, such as the living will and the power of attorney for health care, with all my patients; do you have any questions about them?” or “I discuss medical values with all my patients; have you ever discussed them with your family?”

• Personal values ultimately guide patient decision making. Patients must be asked whether they want to live at all costs or whether they might compromise some life expectancy for a better quality of life. Patients must also be asked about a variety of other potentially competing values, such as maintaining mobility and physical independence, maintaining the ability to think clearly and communicate with others, being treated in accordance with their cultural and religious/spiritual beliefs, not becoming a burden on family, and avoiding unnecessary pain and suffering.

• Advance directives are written or oral instructions that enable patients to guide their future health care decisions in the event that they cannot do so themselves.

• Living wills are documents that allow patients to choose one of two or three scenarios for their end-of-life care (choices vary by state): Do everything medically possible to maintain life; do no extraordinary intervention but maintain comfort and allow death to occur “naturally”; or do no extraordinary intervention but continue nutrition and hydration in addition to other comfort care. In most states, laws require a patient to be diagnosed as terminal (prognosis less than 6 to 12 months) by two physicians for a living will to be legally binding.

• Durable powers of attorney for health care (DPAHC) are legal documents that enable patients to appoint another specific individual (known as a proxy, agent, or surrogate) to make decisions for them, should they be unable to do so for themselves. These documents are most effective when patients and their surrogates have thoroughly discussed treatment options, so that the standard of substituted judgment may be applied (see below). Many DPAHC documents include a “living will” section within them. Patients do not need a lawyer to complete a DPAHC.

• Many states now have POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) documents. Signed by the patient (or surrogate) and physician, the POLST is a set of orders that travels with patients to all sites of care—home, hospital, skilled nursing facility, etc. Most POLST documents have three sections:

a. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation—Attempt or Do Not Attempt CPR if a patient has no pulse and is not breathing;

b. Medical Interventions—Comfort Only; Limited Interventions (such as intubation, antibiotics, dialysis, blood products, etc., while the patient is not in “arrest”); or Full Treatment;

c. Artificially Administered Nutrition—no artificial nutrition (including feeding tubes); allow a trial of artificial nutrition; or accept long-term artificial nutrition.

• Oral directives are the most common kind of advance directives and are often sufficient in guiding terminal care decisions. Unfortunately, the legal benefits of oral directives to family and friends vary by state and may not be upheld in cases of a family dispute or family physician disagreement. Oral directives to physicians, on the other hand, when clearly documented in the medical record, are usually honored by the courts.

• Medical decision-making capacity refers to the ability to make a rational decision about medical treatment options. Capacity should be viewed on a sliding scale: a patient may have the ability to understand and make decisions about some treatment options but not others, and this ability should be re-evaluated for each pending decision. Determining capacity requires assessment of a patient’s ability to accept responsibility for making the treatment decision; to understand the medical situation and prognosis; to understand the alternatives for care; to decide on an alternative based on reasoning that fits his or her general goals and values; and to communicate that decision clearly. Appropriate questions include, “What can you tell me about your condition?” “What is your understanding of this treatment and why do you think it is right for you?” “What can you tell me about the alternatives we’ve discussed?” Medical decision-making capacity should not be confused with competency, which is a legal status determined by a court of law.

• Surrogacy. When an individual does not have medical decision-making capacity, surrogate decisions must be made. When possible, a legal surrogate, appointed by the patient in a DPAHC, should make decisions. A POLST or living will may also guide care. When these are not available, surrogate decision makers should generally follow the traditional family hierarchy: spouse, adult children, parents, siblings, other relatives, and friends. The two standards most often used for making surrogate decisions are substituted judgment (“If the patient were still able to make decisions for herself, what would she want in this situation?”) and best interests (“What do you think is the best thing to do for the patient, all things considered?”).

Surrogate decision making is very stressful for most people. Ideally, patients and surrogates should discuss choices and values beforehand, with patients directing surrogates to follow previously-expressed preferences. Alternatively, patients should empower surrogates to simply use their own judgment and make decisions for the patients they are representing the same way they would for themselves.

MEDICAL CARE ISSUES

Palliative Care is a team approach to caring for the “whole person,” and focuses on improving quality of life for patients and their families who are experiencing a life-threatening or life-limiting illness or injury. It facilitates comprehensive care for patients who are at any stage in the continuum of their illness, which may include curative, chronic management, and end of life. Palliative Care takes place in any care setting, and does not preclude interventions and therapies (such as hospitalization, IV antibiotics, IV fluids, High-Flow Therapy [Vapotherm], BiPAP, intubation, thoracentesis, paracentesis, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and CPR) that are consistent with the patient’s goals of care.

In contrast, Hospice is intended for patients who are at the end stage on the continuum of their illness. Hospice should be strongly considered if the patient has 6 months or less to live based on the expected natural course of their illness. Instead of using doctors’ offices, clinics, urgent cares, or ERs, patient care is provided at the patient’s home, nursing home, or “hospice house” and typically does not involve invasive therapies. The goal of Hospice is to allow a patient a natural death while minimizing suffering, so that patients may carry out those goals that are most important to them. If symptoms cannot be controlled at the home, patients may be admitted to the hospital under the General Inpatient Hospice Coverage for several days without having to revoke their Medicare Hospice benefit. Additionally, hospice provides bereavement follow-up for 13 months after the patient’s death. Hospice may be viewed as a subset of Palliative care.

DOMAINS OF PAIN

The domains of care for both Hospice and Palliative Care relate to the domains of pain as described by Cicely Saunders SW, RN, MD (considered the founder of the modern hospice movement), who focused on treating a patient’s “Total Pain.” Total Pain refers to Physical Pain, Emotional Pain, Social Pain, and Spiritual Pain.

• Physical pain (discussed in greater detail below and elsewhere in this manual) includes nociceptive, neuropathic, and mixed pain syndromes. Other aspects of physical suffering within this domain include dyspnea, nausea, dysphagia, fatigue, anorexia–cachexia, and delirium.

• Emotional pain includes symptoms such as anxiety and depression. Patients with a terminal illness often experience a predictable and normal grief reaction. Grief usually follows a typical progression: shock/disbelief, denial, anger, bargaining, guilt, depression, and finally, acceptance/hope. Some aspects of emotional pain should be normalized, and do not require “medical” treatment. For example, it is normal for a person to feel angry and sad when they have an incurable disease. However, when emotional pain interferes with meaningful activities, goals, spiritual discovery, and relationships medical intervention is warranted (see below).

• Social pain refers to barriers in a patient’s support network and infrastructure. Social pain can arise from damaged relationships, loss of cultural identity, language barriers, homelessness, loss of work, poverty, and loss of medical insurance are essential in maximizing therapeutic gain. Strategic use of family meetings, with involvement from clinical social workers and medical interpreters, can be very instrumental in recognizing and addressing social pain.

• Spiritual pain includes the disruption in one’s ability to find sources of strength, hope, joy, and sense of purpose. Spirituality does not necessarily equate with a belief in God or a specific religion. Spirituality can be any connection a patient experiences that brings peace, hope, joy, and sense of purpose. For example, a patient may define their spirituality through a love of nature, cooking, gardening, or being with family and friends. It is important to begin with taking a spiritual history taken from EPERC Fast Fact #019 (Table 22.5-1).

• The premise for diagnosing Total Pain is that each domain of pain: Physical, Emotional, Social, and Spiritual, impacts the other domains creating a harmful synergy. By the same token, improving pain symptoms in one domain has the potential to improve symptoms found in the other domains, thereby creating a beneficial synergy. For example, a patient dying of ovarian cancer who is estranged from her adult son (social pain) may experience a lower threshold of her physical, emotional, and spiritual pain. Assisting in healing the relationship with her son will relieve her social pain and allow her to experience a higher threshold for her physical, emotional, and spiritual pain symptoms.

Taking a Spiritual History |

S—spiritual belief system

• Do you have a formal religious affiliation? Can you describe this?

• Do you have a spiritual life that is important to you?

• What is your clearest sense of the meaning of your life at this time?

P—personal spirituality

• Describe the beliefs and practices of your religion that you personally accept.

• Describe those beliefs and practices that you do not accept or follow.

• In what ways is your spirituality/religion meaningful for you?

• How is your spirituality/religion important to you in daily life?

I—integration with a spiritual community

• Do you belong to any religious or spiritual groups or communities?

• How do you participate in this group/community? What is your role?

• What importance does this group have for you?

• In what ways is this group a source of support for you?

• What types of support and help does or could this group provide for you in dealing with health issues?

R—ritualized practices and restrictions

• What specific practices do you carry out as part of your religious and spiritual life (e.g. prayer, meditation, services, etc.)

• What lifestyle activities or practices do your religion encourage, discourage or forbid?

• What meaning do these practices and restrictions have for you? To what extent have you followed these guidelines?

I—implications for medical care

• Are there specific elements of medical care that your religion discourages or forbids? To what extent have you followed these guidelines?

• What aspects of your religion/spirituality would you like to keep in mind as I care for you?

• What knowledge or understanding would strengthen our relationship as physician and patient?

• Are there barriers to our relationship based upon religious or spiritual issues?

• Would you like to discuss religious or spiritual implications of health care?

T—terminal events planning

• Are there particular aspects of medical care that you wish to forgo or have withheld because of your religion/spirituality?

• Are there religious or spiritual practices or rituals that you would like to have available in the hospital or at home?

• Are there religious or spiritual practices that you wish to plan for at the time of death, or following death?

• From what sources do you draw strength in order to cope with this illness?

• For what in your life do you still feel gratitude even though ill?

• When you are afraid or in pain, how do you find comfort?

• As we plan for your medical care near the end of life, in what ways will your religion and spirituality influence your decisions?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree