2 The therapeutic relationship in phytotherapy

The challenge of the therapeutic relationship

What is the ‘therapeutic relationship’?

The variety of relationship models in healthcare

Patient expectations: clarification and challenge

New perspectives on the placebo effect

Setting the context in which a therapeutic relationship can emerge: the importance of practitioner factors

Reflective practice: nurturing the ‘therapeutic attitude’

Evidence-based medicine and the therapeutic relationship

Phenomenology: the felt presence of the body in the moment

The relevance of the therapeutic relationship in phytotherapy: weaving the loose threads

The Challenge of the Therapeutic Relationship

Influence 1: The individual’s innate ‘self-healing’

Influence 2: Changes to thoughts, behaviours and activities (attitudinal, behavioural, nutritional, relating to exercise and lifestyle, etc.)

Influence 3: The therapeutic relationship between the person and carer/s

Both conventional and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioners may assume that, in the cases where it is deployed, the fourth type of influence is usually the most significant, but this is not necessarily (or even usually) the case. Practitioner hubris may ascribe healing to the intervention they have applied, when in truth it has played only a minor part, if any, in the process. Indeed, it may even have obstructed and slowed down achievement of the eventual positive outcome – or prevented it from ever occurring. Although it is self-evident that the animal organism is self-healing (e.g. a small wound will repair without any medical intervention), this fundamental – and most vital (I choose this word carefully) – capacity is often ignored or overlooked. Parsons’ (1951) observation on the relationship between self-healing and practitioner effects still rings true:

We can, however, take the practitioner out of the four proposed spheres of influence. All four can apply without a ‘healthcare professional’ being involved. The therapeutic relationship in ‘Influence 3’ may be created with a friend, family member, colleague, cleric, etc. Later in this chapter we will consider the practitioner qualities that help to facilitate the therapeutic relationship as described by the psychotherapist Carl Rogers. He came to realize that these qualities were not specific to healthcare practitioners (and that they can, in fact, occur in anybody in any field or role), and later promoted their application by non-medical practitioners such as teachers (Rogers & Freiberg 1994).

What is the ‘Therapeutic Relationship’?

• Negative: upset, fear, anxiety, uncertainty, confusion, helplessness, hopelessness, irritation, frustration, etc.

• Positive: hope, reassurance, comfort, enlightenment, insight, relief, empowerment, uplifted, focussed, etc.

A number of popular sayings and phrases attest to the potency of positive encounters:

We might readily accept this assertion in the context of psychological therapies, where no material remedies are given, yet the patient may nonetheless gain benefit. It could be argued that therapeutic results accrue in the psychotherapies because these approaches use prescribed systems of interviewing, framing and advice-giving that are constructed to constitute a formal ‘remedy’ and that these are missing from other healthcare approaches. That is to say that the psychological consultation is designed and intended to be therapeutic whereas that occurring in the non-psychotherapies is not. The particular format that the psychological consultation follows appears to be of little importance however, since, as Hyland (2005) observes: ‘meta-analyses lead to the conclusion that all psychotherapies are equally effective.’ Hyland contends that training in particular practitioner skills or techniques is less important than the practitioner’s ‘therapeutic attitude’ or ‘therapeutic intent’. The practitioner’s belief ‘in what they are doing’ combined with a warm and caring approach towards the patient are what matters. Hyland cites Rogers (1951) in describing some of the basics involved in the latter of these areas:

Although much of the literature pertaining to the therapeutic relationship derives from the field of psychotherapy, the concept does not apply in this field alone. The broad principles of the therapeutic relationship can be applied in any healthcare modality – indeed in any helping or caring interaction between people. Hyland (2005) presents one view which states that: ‘psychotherapy provides a context that promotes self-healing rather than treats disease, and should coexist with conventional medicine as a parallel but different kind of treatment …’. Yet is it really necessary to maintain this distinction between psychological and material therapies? McWhinney et al. (1997) have contended that:

At this stage, it is worth distinguishing between the concept of the therapeutic relationship and that of ‘therapeutic alliance’. Many authorities use the two terms interchangeably but we may consider the latter term as having to do with the specific work of creating a shared sense of positive collaboration between patient and practitioner. This concerns trust-building and other factors that bring the patient ‘onside’ with the practitioner and enable a course of treatment/therapy to take place. In this sense, the therapeutic alliance may be viewed primarily as a means of improving patient compliance with treatment, which is an especially relevant concern where there may be challenges to compliance such as in treating those who are alcohol dependent (Ernst et al. 2008). The therapeutic relationship can be conceptualized as being much broader than this and as being not just a means to ensuring compliance with the ‘active treatment’ but of potentially being an active treatment in itself. This newer, extended view of the possibilities of the therapeutic relationship is made possible to a great degree by the emerging field of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI), which connects psychology with physiology and offers a way of informing the mind–body question by measuring and correlating the biochemical changes that accompany psychological states. Janice Kiecolt-Glaser, one of the key researchers in this field, contends that: ‘The link between personal relationships and immune function is one of the most robust findings in PNI’ (Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2002) and she and her co-workers have studied the ‘pathways through which hostile or abrasive relationships affect physiological functioning and health’.

The therapeutic relationship, then, is a positive potential that exists when practitioner and patient interact with each other. Understanding it and knowing how to facilitate it is likely to result in benefits for both parties. A critical appreciation of the concept is necessary, however, e.g. Chew-Graham et al. (2004) have seen a problem in what they consider to be an inappropriate elevation of the practitioner–patient relationship such that practitioners may feel compelled to seek to: ‘maintain relationships with patients, even though they felt powerless to achieve useful clinical outcomes and felt forced to collude with illness behaviour that sustained incapacity’. This is the very opposite of a therapeutic relationship and the components and characteristics of the therapeutic approach must be appreciated in detail and in context in order to realize its potential in the consultation.

The Variety of Relationship Models in Healthcare

In discussing the scope of the therapeutic relationship, Agich (1983) refers to Szasz and Hollender’s (1956) classification of the three basic models of doctor–patient relationships:

1. Activity–passivity (the doctor actively does something to the patient, which they passively receive)

2. Guidance–cooperation (the doctor tells the patient what to do and the patient complies)

While the optimally conducive territory for developing the therapeutic relationship would seem to lie with the mutual participation model, Agich (1983) points out that there are times when other models are appropriate, indeed they may be essential, e.g. a coma patient requires application of the activity–passivity model. In fact we can imagine (if we extend the number and types of relationships involved in a particular situation) a scenario where all three models may be employed simultaneously: a practitioner called to a serious accident site may treat an unconscious patient using activity–passivity; direct others at the scene using guidance–cooperation and work with colleagues using mutual participation. The most effective practitioners may be those who are able to move between models as appropriate. We will come back to this notion of adaptability as a key feature distinguishing the practitioner who is better able to form therapeutic relationships later.

Agich (1983) cautions against making the error of seeing the therapeutic relationship as: ‘a free-standing relationship between autonomous individuals which abstracts from all social connections’. The autonomy of both practitioner and patient may be limited or constrained to some degree and the patient’s situation is impacted by numerous influences besides those that might be considered strictly ‘medical’ in nature. While many practitioners, especially in the CAM bracket, make broad claims to ‘treat the cause, not the disease’ and to ‘treat the whole person’ the difficulties inherent in getting to know a fraction of what constitutes the ‘whole person’, let alone getting to anything as singular as the ‘cause’ of a condition (particularly in complex cases), should not be trivialized. In order to gain the fullest possible view of the patient’s situation a holistic approach is essential, but in asserting this we may need to pause for a moment of clarification since the term ‘holistic’ has come to sound trite to many ears due to overuse, misapplication and ill-definition. Gordon’s (1982) take on the nature of holism in healthcare still ranks amongst the most concisely useful:

Looking outside of the narrowly ‘medical’ consultation zone requires a view of how health and medicine are situated within, and impacted by, sociocultural factors. To enable this expanded way of seeing and knowing the practitioner can look to a wide range of relevant fields of study (many of which tend to be overlooked or underexploited by healthcare practitioners of every stripe) such as that of the sociology of health and illness (see Nettleton 2006, for a solid introduction to this field). Part of the challenge of the therapeutic relationship is that it pushes the practitioner to continually develop and reframe their knowledge and skills as they seek to learn from the patient. To intentionally set up the consultation as a laboratory for personal and professional change and development in this manner constitutes a radical political act that may transgress and subvert both the general model that the practitioner was originally trained in and particular protocols that they may be expected to comply with.

The terms ‘healthcare practitioner’ and ‘political radical’ may strike us as antithetical. The dominant conventional medical services deliver the healthcare messages and practices sanctioned by the government and its departments – so that healthcare workers become agents of the state. This places limits on the autonomy of the practitioner. Medicine is an inherently conservative profession – both in its modern and traditional forms. Necessarily so, one might argue, since new approaches and techniques should only be added to the canon once they have been tried and tested. Yet conservatism may both mask and maintain useless or harmful attitudes and practices. It can be very hard for healthcare practitioners (whether conventional or CAM) to see beyond the edges of their own medicalized worldview – within this they live and breathe and have their professional being. Practitioners are restricted by their auto-medicalization, just as society at large is conditioned and constrained by notions of what is medically appropriate and acceptable. In his seminal critique of conventional medicine, Ivan Illich (1976) described the nature of the problem:

Since Illich’s attack, mainstream medicine has delved more deeply into the body as increasingly penetrating techniques and conceptualizations (e.g. the MRI-revealed body and the genomic body) have been developed. Ever greater reliance on technical means of understanding and reading the body undercuts attempts made elsewhere within medically-related fields (such as public health) to increase patient autonomy since the definitive answers to Illich’s questions (‘what constitutes sickness, who is or might become sick, and what shall be done’?) still rests with medical experts. We may query, by contrast, the extent to which CAM has been successful in proposing alternative ways of comprehending the body and to what extent it has promoted an ethos valuing greater personal empowerment to evolve. For medical doctor, columnist and noted CAM-critic, Ben Goldacre (2008), CAM is merely part of the problem, another group contributing to the ‘medicalisation of everyday life’:

General discussions about the role of CAM are flawed where they presuppose that CAM represents a coherent and organized alternative schema to mainstream medicine, i.e. that it is a discrete entity fit for comparison with its supposed antithesis. To proceed in such a way would be to make a category error. ‘CAM’ is essentially a definition of exclusion – which is to say that all healthcare practices outside of ‘conventional/mainstream’ medicine (i.e. the dominant model) are bracketed as ‘CAM’. Closer inspection reveals the heterogenous nature of the individual therapies constituting the notion of CAM, and differences between the agendas and messages of corporate interests (manufacturers of CAM remedies) and particular groups of practitioners. It may be more accurate to join Kelner and Wellman (2000) in viewing CAM as: ‘a complex and constantly changing social phenomenon which defies any arbitrary definition or classification’. How can we gauge the impact of such an amorphous entity on models in the consultation? Most texts that set out lists of the characteristics of CAM assert that a mutual participation model is used by its practitioners, e.g. Fulder (1996) provides eight ‘unique features of complementary medicine’, one of which is the ‘patient as partner’. What is the nature of this partnership though, and how can we know if it has been achieved? In suggesting answers, it may be helpful to return to Illich (1976), noting the distinction he draws between:

We can briefly note here that the gradual shift in medicine from paternalistic (heteronomous) to patient-centred (valuing patient autonomy) models that we will explore shortly, reflects what Taylor (2009) has described as a: ‘shift that has occurred … from a culture where beneficence is the dominant ethical principle to one in which autonomy is valued as highly’. (Note: Beneficence inclines to paternalism where attempts to benefit an individual are made against their will.)

In any case, CAM practitioners are not immune from the tendency to ‘mystify and expropriate’ – a potential pitfall for all healthcare professionals. We can suggest, nonetheless, that a key criterion in estimating a practitioner’s success in establishing healthy partnerships with patients has to do with the extent to which they are able to empower autonomy and minimize dependency on other-administered ‘maintenance and management’. CAM practitioners have an edge here, which may have less to do with the founding philosophies of their particular modality and more to do with the fact and implications of their ‘excludedness’, especially with regard to what Sharma (1994) has called the ‘institutional context’. The differing operating conditions for conventional and CAM practitioners significantly affect their respective capacities for professional autonomy, as Sharma explains:

While complementary therapists:

The logical conclusion of this line of argument, namely that the non-statutory nature of CAM therapies constitutes a strength (although one that may be offset by a number of weaknesses, such as a lack of accountability); adds a further critical dimension to the discussion of the regulation of CAM professions opened up in the previous chapter. Considerations in this territory relate not only to outcomes for patients but for practitioners themselves, as Moynihan and Smith (2002) make clear as they reflect on the extent of biomedicalization and its impacts on conventional practitioners:

It is worth noting that ‘trying to cope with increasing demand with inadequate resources’ constitutes a definition of the cause of professional burnout – a condition characterized by ‘exhaustion, cynicism and sense of inefficacy’ (Maslach 2003). Approaches that enhance patient autonomy are more sustainable for the practitioner and for national economies such that these two factors are likely to increasingly drive mainstream healthcare in the direction of a patient-centred model of practice and service provision.

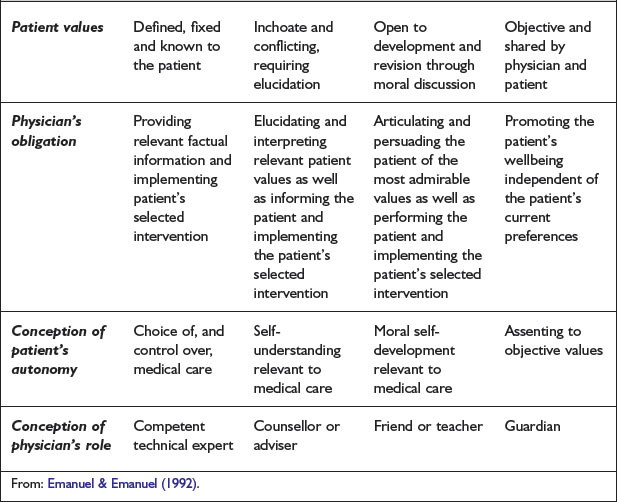

At this point, let us add to Szasz and Hollender’s (1956) three basic models of doctor–patient relationships by considering later contributions to this subject area in order to better appreciate its scope. In discussing the ‘struggle over the patient’s role in medical decision making’, Emanuel and Emanuel (1992) outlined four models of the physician–patient relationship:

1. Paternalistic (alternatively called the ‘priestly’ or ‘parental’ model): Here the practitioner determines what is best for the patient, with little explanation given to the patient and minimal patient involvement. The patient is expected to assent to the practitioner’s decisions.

2. Informative (also known as the scientific, engineering or consumer model): In this model, the practitioner aims to ‘provide the patient with all relevant information, for the patient to select the medical interventions he or she wants, and (then) to execute the selected intervention’. In this model, the practitioner is a provider of facts, which the patient interprets according to her values. There is ‘no role for the physician’s values, the physician’s understanding of the patient’s values, or his or her judgement of the worth of the patient’s values’.

3. Interpretive: In contrast to the informative model the practitioner’s aim is to ‘elucidate the patient’s values and what he or she actually wants, and to help the patient select the available … interventions that realize these values’. Information on the options is provided in conjunction with assistance based on appreciation of the patient’s values.

4. Deliberative: This model sees the patient’s health-related values as open to discussion, such that the practitioner is able to suggest ‘why certain health-related values are more worthy and should be aspired to … the physician aims at no more than moral persuasion; ultimately, coercion is avoided, and the patient must define his or her life and select the ordering of values to be espoused’.

A summary of these four concepts, with correlations including the view taken of the patient’s autonomy is provided in Table 2.1.

It is interesting to consider these models in the light of the evidence-based medicine (EBM) discussion, which we began in the previous chapter and will return to again below, particularly around the original definition of EBM as: ‘the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values’ (Sackett et al. 2000). In applying the four models to a hypothetical clinical case, Emanuel and Emanuel (1992) largely interpret ‘information’ and ‘facts’ as research so that their discussion focuses on the three territories of EBM, with difficulties in the patient–practitioner relationship occurring particularly when research and/or clinical expertise are emphasized to the detriment of due attention to patient values.

Each of the four models is problematic when viewed as representing a single and permanent way of being as a practitioner. Rather we can assert, as earlier, that the most effective practitioners are likely to be those who are able to move between these models as appropriate – frequently within the course of just one consultation. These are not models of practice, then, but caricatures of practitioner strategies that can be deployed and combined as a given situation requires. As Emanuel and Emanuel (1992) point out, even paternalistic behaviour can be appropriate in situations of medical emergencies.

In selecting which of the four models might generally be preferred as ‘the ideal physician–patient relationship’, Emanuel and Emanuel (1992) choose the deliberative model, rejecting allegations that it merely represents ‘a disguised form of paternalism’ – this reading is far from safe, however, since the model suggests that practitioners occupy a position of definitive moral and epistemological authority and little recognition of the role of uncertainty is made. The central issue of uncertainty, that lies within and between the practitioner’s and the patient’s views of how to proceed in a given situation, tends to be overlooked in discussions of ‘shared decision-making’ models such as the deliberative.

The types of autonomy afforded to the patient within Emanuel and Emanuel’s (1992) four models all stand in relation to various ways of negotiating conventional medical care but they are equally relevant in CAM practice. Any discussion of patient autonomy is incomplete of course without referencing ways in which people may care for their wellbeing independently of healthcare practitioners through self-care measures, and the degree to which autonomous healthcare is facilitated or hindered by socioeconomic, political and cultural influences. A full discussion of these factors is beyond the scope of this book but we will return to limited discussion of them at various points in the text.

Kaba and Sooriakumaran (2007) have proposed a time line for the evolution of the doctor–patient relationship beginning with ancient Egypt (c.4000–100 BCE) where the paternalistic priest–supplicant relationship is said to form the basis of the practitioner-relationship; through the Greek enlightenment (c.600–100 BCE) where it is proposed that the roots of the mutual-participation model lie; and on through medieval Europe and the inquisition (paternalism revived) and the French revolution (partial egalitarianism shifting emphasis from activity–passivity to the guidance–cooperation model) to the modern era, where the ‘emergence of psychology’, including psychoanalytical and psychosocial theories, has led to a refocusing on the patient as a person. The practitioner–patient relationship, they argue, has fluxed from one pole to the other, with a general trend of movement from a practitioner-centred to a patient-centred approach.

Mead and Bower (2000) have discussed the ambiguity concerning the meaning of ‘patient-centredness’ and have identified five ‘conceptual dimensions’ that they propose as constituting a model for it that distinguishes it from the biomedical model. These are:

1. Biopsychosocial perspective: ‘broadening the explanatory perspective on illness to include social and psychological factors’

2. The patient-as-person: ‘understanding the individual’s experience of illness … (and) as an idiosyncratic personality within his or her unique context’

3. Sharing power and responsibility: ‘concerned to encourage significantly greater patient involvement in care’

4. The therapeutic-alliance: ‘(which) has potential therapeutic benefit in and of itself’

5. The doctor-as-person: ‘emotions engendered in the doctor by particular patient presentations may be used as an aid to further management’.

This formulation represents a sort of ‘coming-out’ of conventional medics as sensitive, feeling people who are open to the subjective elements of the consultation – a vulnerable circumstance that Mead and Bower (2000) immediately defend by proposing ways in which patient-centeredness can be measured!

McWhinney (1996) contends that: ‘The essence of the patient-centred method is that the doctor attends to feelings, emotions and moods, as well as categorizing the patient’s illness’. It may seem extraordinary to those outside of medicine that such activity stands in need of emphasis – at least to those who have only had positive experiences of conventional medical care – don’t all ‘good’ practitioners do this? The ability and capacity for practitioners to work in a patient-centred way is influenced by their philosophy of practice and institutional context, as we have previously noted, so that healthier relationships with patients depend in large part on practitioner education and the operating conditions for practice – where either are narrow or constrained it will be difficult for patient-centred practice to emerge. The battle to end paternalism has a long way to go in conventional medicine (Coulter 1999: ‘Paternalism is endemic in the NHS’) and as CAM therapies gradually enter the mainstream, each modality will need to guard against being subsumed into the still predominantly paternalistic ethos of its culture.

Patient Expectations: Clarification and Challenge

The fit between the patient’s expectations and the practitioner’s comprehension of them is frequently a poor one. Britten (2004) has pointed out the dangers that lie in this territory: ‘Inappropriate assessments of patients’ expectations can result in actions deemed unnecessary by the doctor and unwanted by the patient’. There is no reason to suspect that the situation is necessarily any different in CAM consultations. False perceptions of patient’s expectations may lead to a sense of pressure to meet these expectations on the part of the practitioner – even when they consider them unfounded or inappropriate. Britten (2004) cites studies that suggest that: ‘… pressure from patients may be stronger in the doctor’s mind than in the patient’s mind. Doctors may be making inappropriate decisions for the sake of maintaining relationships with patients without checking whether their assumptions about patients’ preferences are correct’. Therapeutic practitioners need to be on guard against this type of misunderstanding and adopt the strategy of repeatedly asking questions to clarify patients’ expectations, desires and wishes. Asking such clarifying questions can move both practitioner and patient out of their comfort zones and occasionally, this type of question may lead to profound moments of insight that can catalyse reflection and change. The potential for such crucial episodes to have negative outcomes is diminished when questions are phrased non-judgementally. An example:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree