16 The small and large intestine

Surgical anatomy and physiology

Anatomy and function of the small intestine

Summary Box 16.1 Clinical assessment of a patient with gastrointestinal symptoms

• Gastrointestinal symptoms are very common

• Most symptoms are due to self-resolving illness

• Patient age is an important factor when considering the differential diagnoses

• Duration of symptoms is an important arbiter of the need for investigation

• Careful assessment of the nature and severity of symptoms is important and may indicate peritonitis, obstruction or severe inflammation

• Symptoms of self-resolving intestinal disorders that are managed conservatively are often indistinguishable from major problems

• Investigation usually involves endoscopy and imaging, as well as stool culture.

strong submucosa and comprises a single layer of columnar cells in a villiform structure that dramatically increases the absorptive surface area. Columnar glandular epithelium is interspersed with mucus-secreting cells, Paneth cells and amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation (APUD) cells derived from the neural crest. Between the inner layer of circular muscle and the outer longitudinal layer runs Auerbach’s myenteric plexus, which comprises vagal parasympathetic fibres and sympathetic fibres from the lesser and greater splanchnic nerves. This plexus controls orderly propulsive contractions of the muscular layers of the gut wall. The sympathetic nervous system mediates the sensation of visceral pain, and a submucosal plexus (Meissner’s plexus) of autonomic nerves innervates the glandular cells in the epithelium.

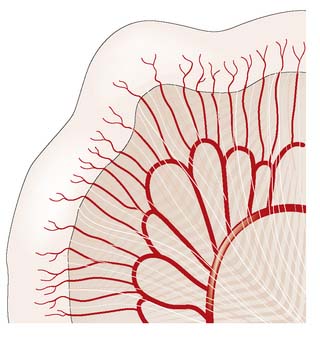

The small intestine is supplied by the superior mesenteric artery, which runs in the root of the small bowel mesentery, supplying the bowel by a series of arterial arcades (Fig. 16.1). These midgut vessels communicate with the coeliac axis through the pancreaticoduodenal arcade. The superior mesenteric supply also communicates with that of the inferior mesenteric artery by contributing to the colonic marginal artery through the left branch of the middle colic artery, which joins to the ascending branch of the left colic artery. Venous blood drains via the superior mesenteric vein to the portal vein. Lymphoid aggregates in the submucosa (Peyer’s patches) are more numerous in the ileum, and lymph drains to regional nodes in the root of the mesentery before passing to the cisterna chyli.

Anatomy and function of the large intestine and appendix

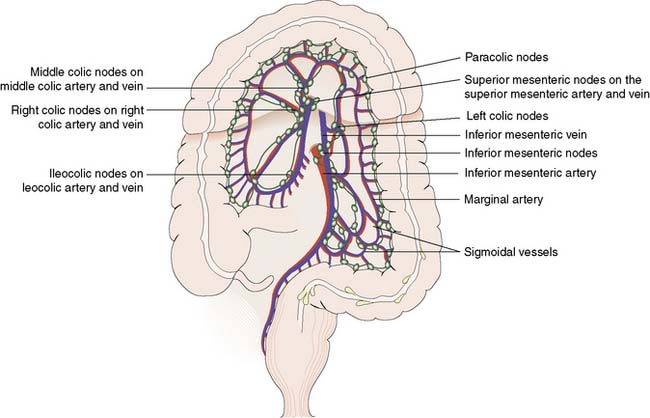

The inferior and superior mesenteric arteries supply the colon and anastomose via a marginal artery (Fig. 16.2) that allows collateral supply in the event of arterial occlusion, but at the splenic flexure this arterial communication may be tenuous. The superior rectal artery is the continuation of the inferior mesenteric artery, supplying the rectum and anastomosing with the middle and inferior rectal arteries (branches of the internal iliac arteries). The inferior mesenteric vein drains into the splenic vein. Lymph channels run along the course of the arterial supply, draining to epicolic and paracolic nodes close to the bowel wall, and to regional nodes at the origin of the superior and inferior mesenteric vessels (Fig. 16.2). Lymph from the rectum drains upwards to superior rectal and inferior mesenteric nodes, whereas anal canal lymph drains to inguinal nodes. Knowledge of the lymphatic drainage has considerable relevance to surgical lymphadenectomy performed as part of radical cancer clearance, as well as to radiotherapy for rectal and anal cancers.

Clinical assessment of the small and large intestine

Disorders of the appendix

Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis remains the most common acute abdominal emergency in childhood, adolescence and early adult life and is discussed in Chapter 12.

Appendiceal tumours

Adenocarcinoma of appendix

Summary Box 16.2 Tumours of the appendix

• Around 85% of all appendiceal tumours are carcinoids, the appendix being the most common site of carcinoid tumour in the gastrointestinal tract

• Carcinoid tumours are found in 0.5% of surgically removed appendices

• Size > 2 cm indicates increased risk of malignancy, but lymph node involvement is rare and metastases are extremely rare

• Appendix adenocarcinoma is rare and may be associated with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)

• Mucin-secreting cystadenoma, if ruptured, may lead to pseudomyxoma peritonei

• Pseudomyxoma peritonei is a rare, capricious condition that causes pressure symptoms on intestine and other intra-abdominal organs, and for which there is no curative therapy.

Inflammatory bowel disease

In view of the similarities in clinical presentation and in some aspects of management, it is useful to discuss Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis together (Table 16.1). Ulcerative colitis affects the colon and rectum exclusively, whereas Crohn’s disease may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract. Inflammation is restricted to the mucosa in ulcerative colitis but transmural inflammation is a hallmark of Crohn’s disease. There are also important implications for prognosis, as surgery for ulcerative colitis is curative, whereas Crohn’s disease frequently follows a relapsing course, despite medical or surgical intervention.

Table 16.1 Clinical features of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

| Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 5–7 per 100 000 and rising | 10 per 100 000 and static |

| Extent | May involve entire gastrointestinal tract | Limited to large bowel |

| Rectal involvement | Variable | Almost invariable |

| Disease continuity | Discontinuous (skip lesions) | Continuous |

| Depth of inflammation | Transmural | Mucosal |

| Macroscopic appearance of mucosa | Cobblestone, discrete deep ulcers and fissures | Multiple small ulcers, pseudopolyps |

| Histological features | Transmural inflammation, granulomas (50%) | Crypt abscesses, submocosal chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, crypt architectural distortion, goblet cell depletion, no granulomas |

| Presence of perianal disease | 75% of cases with large bowel disease; 25% of cases with small bowel disease | 25% of cases |

| Frequency of fistula | 10–20% of cases | Uncommon |

| Colorectal cancer risk | Elevated risk (relative risk = 2.5) in colonic disease | 25% risk over 30 years for pancolitis |

| Relationship with smoking | Increased risk, greater disease severity, increased risk of relapse and need for surgery | Protective, first attack may be preceded by smoking cessation within 6 months |

Crohn’s disease

Pathology

Macroscopically, Crohn’s disease produces a cobblestone appearance, in which oedematous islands of mucosa are separated by crevices or fissures; these can extend through all coats of the bowel wall. Serpiginous ulceration is common so that fibrosis may result in multiple strictures of varying length. Multiple areas of inflammation are common with intervening normal bowel (skip lesions, Fig. 16.3). Full-thickness involvement of the bowel wall leads to serosal inflammation, adhesion to neighbouring structures, and sinus or fistula formation. Microscopically, there are deep fissuring ulcers, oedema and inflammatory cell infiltrates with foci of lymphocytes and non-caseating granulomas in 50% of cases.

Clinical features

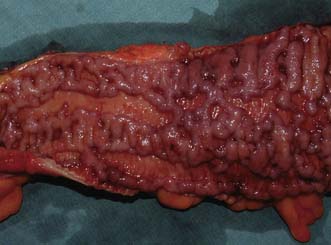

Examination may reveal malnutrition and there may be a palpable abdominal mass. There may be features of subacute intestinal obstruction, and this may be due to active disease, stricturing of ‘burnt-out’ disease, or adhesions from previous surgical intervention. Fistula formation occurs in 20% of patients with small and large bowel disease, but less in those with disease restricted to the large bowel. Fistulae may communicate with adjacent loops of bowel, other viscera (e.g. bladder, vagina) or the skin. External fistulae may result from surgical intervention and commonly involve the anterior abdominal wall or perineum (Fig. 16.4). Abscesses can result from chronic bowel perforation, but free perforation is relatively uncommon because the inflamed segment usually adheres to surrounding structures. Although less common than in ulcerative colitis, toxic dilatation can complicate colonic disease. Fulminant Crohn’s colitis is shown in Figure 16.5; deep ulcers and fibrosis with mucosal oedema and inflammation can be seen.

Investigations

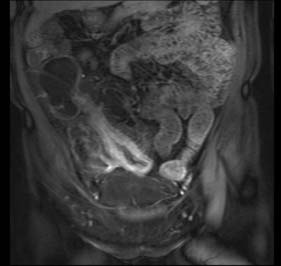

Assessment of nutritional status, including serial weight measurement, is essential. Anaemia may be due to: iron deficiency from chronic blood loss and rarely due to malabsorption; a normocytic anaemia of chronic disease; macrocytic anaemia from vitamin B12 or folate malabsorption. Elevated acute-phase proteins such as C-reactive protein are useful in monitoring disease, though not specific for diagnostic purposes. Until recently, the diagnosis was most frequently made on barium follow-through: typical features are shown in Figure 16.6 – rose-thorn ulcers, long irregular terminal ileal stricture at the site of previous ileocaecal resection. Active disease produces radiological evidence of thickening, luminal narrowing and separation of loops, and is often associated with mucosal ulceration, deep fissuring ulcers and cobblestone appearance. Skip lesions and fistula formation may be apparent. However, MRI enteroclysis (image enhanced by administering oral osmotically active agent – e.g. PEG) has progressively become the investigation of choice (Fig. 16.7), which also has the advantage of limiting radiation exposure. Rectal examination, proctoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy determine disease extent and biopsy of inflamed bowel is mandatory. Newer investigative techniques include video-capsule endoscopy (Fig. 16.8), enteroscopy, and CT colonography. Double-contrast barium enema still has a place for assessing disease extent and delineation of fistulae.

Management

Surgical management

1. Onset of complications of luminal disease: fulminant colitis, life-threatening haemorrhage, obstruction, abscess/sepsis, perforation, fistulation.

2. Acute or chronic failure of medical management to control symptoms/disease activity, failure to thrive, complications of medical therapy.

3. Treatment or prophylaxis of malignancy.

4. Perianal disease: abscess, fistula, anorectal stricture (EBM 16.1).

16.1 Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP; IBD Section, British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2004 Sep;53 Suppl 5:V1-16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1867788.

Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups. Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, Dunlop MG, Thomas HJ, Evans GD, Eaden JA, Rutter MD, Atkin WP, Saunders BP, Lucassen A, Jenkins P, Fairclough PD, Woodhouse CR; British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Coloproctology for Great Britain and Ireland. Gut. 2010 May;59(5):666-89. http://gut.bmj.com/content/59/5/666.long

Colonoscopic surveillance for prevention of colorectal cancer in people with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease or adenomas. NICE Guideline. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13415/53641/53641.pdf

Summary Box 16.3 Indications for surgery in Crohn’s disease

• Chronic subacute obstruction due to fibrotic strictures, adhesions or refractory disease

• Symptomatic disease unresponsive to, or poorly controlled by medical management

• Chronic relapsing disease on discontinuation of medical management and steroid dependency

• Complications of medical management (e.g. osteoporosis)

• Concerns about long-term immunosuppression, risk of malignancy and viral/atypical infections

• Onset of malignancy, including colorectal adenocarcinoma and small bowel lymphoma

• Rarely, control of debilitating extra-colonic manifestations such as iritis and sacroiliitis.

Ulcerative colitis

The annual incidence of ulcerative colitis is ∼︀10/100 000 population in Westernized countries but rare in developing countries. The aetiology is incompletely understood, but genetic, immunological and dietary factors all play a part. The disorder may affect any age group but peak incidence is in early adulthood. In the majority of cases, the disease is contiguous, affecting the rectum and extending proximally (see Table 16.1). In 5% of cases, it is segmental and the rectum is occasionally spared. There is substantial risk of colorectal adenocarcinoma in cases with pancolitis. Although ulcerative colitis is primarily a disease of the large bowel, systemic manifestations (iritis, polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, hepatitis, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum) can occur. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) affects 2–5% of cases of ulcerative colitis; it tends to indicate severe disease and predicts complications. Patients with PSC may develop liver failure and require liver transplantation.

Pathology

The characteristic feature of ulcerative colitis is inflammation restricted to the mucosa and submucosa of the large bowel. In severe episodes, there may be full-thickness involvement with inflammatory infiltrate. Abscesses develop at the base of the colonic crypts, which burst and coalesce to form crypt abscesses. These undermine the mucosa, resulting in ulceration (Fig. 16.9) and oedema of the intervening mucosa, which may form inflammatory pseudopolyps. Histologically, as well as ulceration and crypt abscesses, there is chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, crypt architectural distortion and goblet cell depletion, but granulomas are absent. The colon loses its haustrations and becomes thick and rigid. Stricturing is uncommon and its presence should raise the possibility of Crohn’s disease. There can be difficulty in distinguishing ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s colitis both pathologically and clinically, when the term ‘indeterminate colitis’ is used to denote uncertainty. There may even be migration from one disease entity to the other. There are important implications for surgical treatment, since ileo-anal pouch should be avoided in cases of Crohn’s colitis.

Investigations

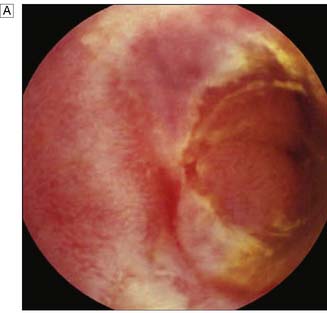

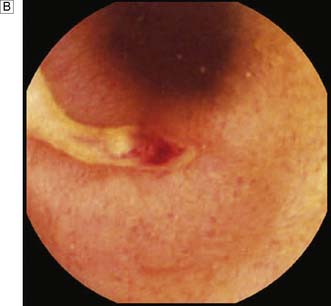

Expert colonoscopy is the mainstay of diagnosis and assessment of disease extent/severity. Endoscopic features of severe acute colitis are shown in Figure 16.10. Barium enema is infrequently used in modern inflammatory bowel disease practice and may risk perforation. Typical changes include loss of haustrations, fluffy granularity of the mucosa, and pseudopolyps. Undermining ulcers may create a double contour to the edge of the colon. Widening of the retrorectal space, due to perirectal inflammation and reduced distensibility of the rectum, is common. In longstanding colitis, the bowel may become short and featureless, resembling a smooth tube (lead-pipe colon). In an acute attack, plain films of the abdomen may reveal a dilated gas-filled colon in which pseudopolyps are evident. When toxic dilatation is suspected, daily plain X-rays are essential to monitor progress (Fig. 16.11). ‘Backwash ileitis’ may produce a dilated and featureless terminal ileum in which the mucosa appears granular. In the acute phase, it is essential to collect stool cultures to exclude supervening bacterial infection and especially C. difficile.

Management

Surgical management

Summary Box 16.4 Indications for surgery in ulcerative colitis

• Symptomatic disease unresponsive to, or poorly controlled by, medical management

• Chronic relapsing disease on discontinuation of medical management and steroid dependency

• Complications of medical management

• Concerns about long-term immunosuppression, risk of malignancy and viral/atypical infections

• Severe dysplasia on surveillance biopsies of colorectal epithelium

• Onset of colorectal adenocarcinoma

• Rarely, control of debilitating extra-colonic manifestations such as iritis and sacroiliitis.

Cancer surveillance in ulcerative colitis

Colorectal cancer risk in long-standing ulcerative colitis is a major factor contributing to surgical decision-making. Carcinoma is typically difficult to detect in colitis, is usually poorly differentiated and has a poor prognosis. Around 2% of all patients will develop cancer at 10 years, 8% at 20 years and 18% at 30 years. In pancolitis, the overall risk is around 25% after 30 years. Early age at first onset (< 15 years), pancolitis, a family history of colorectal cancer and associated PSC are strong cancer risk factors. Cancer surveillance is recommended in the long-term management of patients with chronic ulcerative colitis, and colonoscopy should be performed at 2-yearly intervals (see EBM 16.1). Random biopsies are taken at surveillance colonoscopy, since dysplasia indicates a high risk of cancer. Dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM) is a high-risk indicator of impending, or concurrent, cancer development. Cancer risk for patients with high-grade dysplasia or DALM is > 60% in the next 2 years and so restorative proctocolectomy is recommended. Patients with pancolitis may opt for prophylactic restorative proctocolectomy, especially when ulcerative colitis was diagnosed before the age of 15 years, rather than the uncertainty associated with life-long surveillance.

Disorders of the small intestine

Small bowel neoplasms

Small bowel tumours account for less than 5% of all gastrointestinal neoplasms.

Malignant tumours

Carcinoid tumour

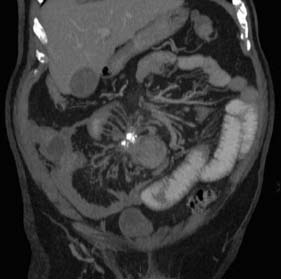

The small bowel is the second most common site for carcinoid tumour (after appendix). Metastasis to lymph nodes is common at presentation, and obstruction and bleeding are the usual modes of presentation. Abdominal CT typically reveals a small bowel mass lesion with prominent calcification (Fig. 16.12). There may be features of the carcinoid syndrome in the presence of liver metastasis. Tests for urinary 5-HIAA (hydroxy-indole-acetic acid) and blood levels of chromogranin A should be undertaken. The primary tumour should be resected where possible. Lesions are frequently multifocal and may require multiple resections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree