Chapter Thirty-Nine. The second stage of labour

Introduction

NICE (2007) advocates that the duration of the second stage (2nd stage) should be 2 h in primigravidae and 1 h in multiparous women. However, women can be unpredictable and may have a second stage that lasts only a few minutes (Downe 2004). Irrespective of how we analyse, divide and measure the 2nd stage of labour, much physical effort is usually provided by the mother over a comparatively short period. The physiological changes that occur in the 2nd stage are a continuation of the forces that have been occurring in the first stage of labour but there is now no impediment to descent of the fetus through the birth canal and to its birth.

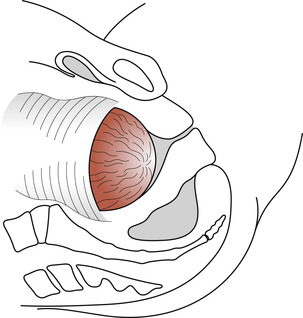

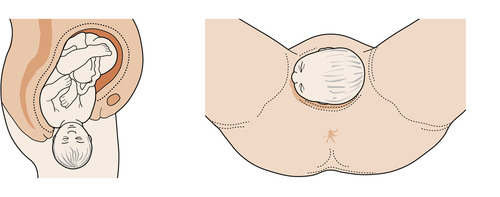

The 2nd stage of labour begins when the cervix is fully dilated (Fig. 39.1) and ends when the fetus is fully expelled from the birth canal. Both midwives and their medical colleagues have used this to base the management of the delivery of the baby according to a time regime. There have been challenges to the concept that the exact timing of the 2nd stage of labour is possible and progress rather than an estimated time limit is probably a more useful indicator of normality.

|

| Figure 39.1 The os uteri is fully dilated and the head enters the vagina. |

Physiology of the second stage of labour

Contractions

There is often a brief lull in uterine activity at the end of the first stage (the latent phase) before the contractions take on their expulsive nature. The character of the contractions changes from that of the first stage. They become longer and stronger but may be less frequent so that the woman and her baby can recover between each expulsive effort. There is continued contraction and retraction of the upper uterine segment (UUS). The fetus descends the birth canal and fetal axis pressure increases flexion and reduces the size of the presenting part.

The secondary powers

As pressure is exerted on the rectum and pelvic floor, a reflex occurs which the woman feels as a compelling urge to push (the active phase). The ‘Ferguson reflex’ has been further explored in Chapter 36. Normal bearing-down efforts made by a woman if left to her own devices occur for about 5–6 s several times during the contraction. Compaction of the fetus occurs during the contraction, and pressure on the fetal head may evoke vagal stimuli, causing a transient fall in fetal heart rate with a rapid recovery. Reduction in oxygen supply due to compression of the placenta will add to this effect. Recent studies suggest that spontaneous pushing will prolong the 2nd stage of labour but cause fewer fetal heart rate changes, higher arterial pH and less damage to the birth canal.

Descent of the fetus

As the fetus descends the birth canal it displaces the soft tissues contained in the pelvis. Anteriorly, the bladder is pushed up into the abdominal cavity, which results in stretching and thinning of the urethra. Posteriorly, the rectum becomes flattened in the sacral curve and any faecal matter will be expelled. The levator ani muscles of the pelvic floor thin out and are displaced laterally. The perineal body is stretched and thinned.

The fetal head now becomes visible at the vulva and advances with each contraction to recede slightly between contractions until crowning of the head occurs (the perineal phase). The head is born and the shoulders and body of the baby are born with the next contraction, accompanied by a gush of amniotic fluid. The 2nd stage culminates as soon as the baby is completely born.

Onset of the second stage

There is often no clear demarcation between the end of the first stage and the beginning of the 2nd stage. Several signs can be taken as indicative that the 2nd stage has begun but the midwife ought to have no difficulty in making the diagnosis. Downe (2003) outlines the presumptive signs of the onset of the 2nd stage of labour and differential diagnoses (Table 39.1). The appearance of several of the signs together may indicate that the 2nd stage of labour has begun but the midwife must use her skills to confirm this. It is sometimes necessary to confirm the absence of cervix by vaginal examination.

| Presumptive sign | Differential diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Expulsive uterine contractions | There may be an urge to push before full cervical dilatation if the rectum is full; this might be more a physiological response in some woman than a pathological response |

| Rupture of the forewaters | This may occur at any time in labour |

| Dilatation and gaping of the anus | Deep engagement of the presenting part and premature maternal pushing may be the cause |

| Anal cleft line | This is the purple-red line which is observed at the cleft of the buttock and climbs up the anal cleft as labour progresses; this requires further evidence |

| Rhomboid of Michaelis | A ‘dome-shaped curve’ is seen in the woman’s lower back. This is displacement of the sacrum and coccyx as the occiput progresses into the sacral curve. The woman throws her buttocks forward, arches her back and throws her arms back to grasp onto something. This is thought to be a physiological response to optimise the process of the fetus through the birth canal by lengthening and straightening the curve of Carus |

| Upper abdominal pressure and epidural analgesia | Women have reported to have upper abdominal pressure when the 2nd stage occurs. More evidence is required to substantiate this finding |

| Appearance of the presenting part | Usually conclusive. However, excessive moulding and caput succedaneum formation may protrude through the cervix prior to full dilatation as may a breech presentation |

| Show | This must be distinguished from bleeding due to premature separation of the placenta |

Duration of the second stage

The duration of the 2nd stage is difficult to predict and in multigravidae may last for as little as a few minutes whereas in primigravidae the process may take up to 2 h (Downe 2004, NICE 2007). There is no good evidence available to impose a time limit for this stage of labour and it is more relevant to base decisions on progress with evidence of adequate uterine contractions, descent and continuing good maternal and fetal well-being. However, NICE (2007) advocate referral of a primigravidae if she has not delivered within 2 h or 1 h for a multigravidae.

Two phases of the 2nd stage of labour can be described as in the first stage of labour: the latent and active phases. The latent phase begins at full dilatation of the cervix but the presenting part may not yet be visible at the pelvic outlet and the woman may not have an urge to bear down. As the fetal head descends due to the force of uterine contractions and stretches the tissues of the vagina and pelvic floor, it will become visible at the vaginal orifice. Once the fetal head is visible, pressure on the rectum will normally provide the reflex stimulus for maternal expulsive pushing and the active phase begins. Pressure of the fetus on the sacral nerves will result in the women experiencing pain from trauma to the tissue and sometimes leg cramp (Coad & Dunstall 2005).

Mechanisms of labour

The fetus is in effect a cylinder which has to negotiate the curved birth canal formed of the bony pelvis and soft tissues of the perineal body. There are two problems with being human and giving birth. One is the curve of the birth canal generated by the upright posture and walking on two legs (bipedalism) and the other is the large size of the baby’s head due to the size of the human brain. Even so, the brain is only one-quarter of the size it will grow to in the adult. Moulding of the skull in order to reduce the presenting diameters is described elsewhere and this section will concern itself with the passive movements that the fetus makes in response to the forces exerted on it by the birth canal.

Collectively, these movements are called the mechanisms of labour and the fetus is turned slightly to take advantage of the widest part of each plane of the pelvis. The reader will remember that the plane of the inlet is widest in the transverse while the outlet is widest in the anteroposterior diameter. Knowledge of mechanisms enables the midwife to use skills in order to facilitate birth with least trauma to mother and fetus. Therefore it is important to take a fetal doll and pelvis and practise these mechanisms until they can be visualised in relation to the unseen movements during the birth of the baby. It is helpful to silently run through these when observing deliveries. It may be life-saving to understand what is occurring inside the woman’s body so that external manoeuvres can be used to complete delivery.

Different mechanisms occur depending on the presentation and position of the fetus and there are principles common to all:

• Descent of the fetus takes place.

• The part of the fetus that leads and meets the resistance of the pelvic floor will rotate forwards to come to lie anteriorly under the symphysis pubis.

• Whatever part of the fetus emerges will pivot around the pubic bone.

The mechanism of a normal labour

There is a classical way of recalling the situation of a fetus at the commencement of the 2nd stage of labour. The terms are described in Chapter 37. The following is for a normal labour:

The movements

The movements involved in the normal mechanisms of labour are:

• Descent.

• Flexion.

• Internal rotation of the head.

• Crowning and extension of the head.

• Restitution.

• Internal rotation of the shoulders and external rotation of the head.

• Lateral flexion.

For illustrations of the movements see Figure 39.2, Figure 39.3, Figure 39.4, Figure 39.5, Figure 39.6, Figure 39.7 and Figure 39.8.

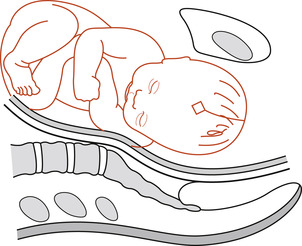

|

| Figure 39.2 Descent of a well-flexed head into the pelvis. The sagittal suture is in the transverse diameter of the pelvis. |

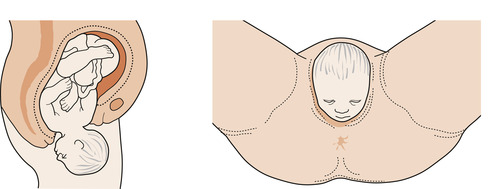

|

| Figure 39.3 Internal rotation. The sagittal suture is normally in the oblique diameter of the pelvis and as further descent occurs rotates into the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis. |

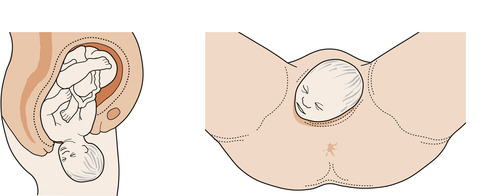

|

| Figure 39.4 Crowning and extension of the head. |

|

| Figure 39.5 Restitution of the head. |

|

| Figure 39.6 Internal rotation of the shoulders and external rotation of the head. |

|

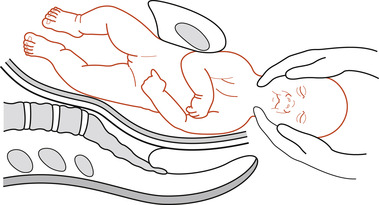

| Figure 39.7 Gentle downward traction is applied to deliver the anterior shoulder. |

|

| Figure 39.8 The posterior shoulder is delivered and then the trunk by lateral flexion. |

Descent (Fig. 39.2)

Descent of the fetal head into the pelvis may have occurred in the antenatal period so that the woman, especially a primigravida, begins labour with the head engaged. This usually indicates that vaginal delivery is likely. The sagittal suture is in the transverse diameter of the pelvis. There is continued descent during the first stage of labour and this is speeded up by maternal effort during the 2nd stage of labour.

Flexion (Fig. 39.2)

The attitude determines which diameter will present in labour. The fetal head is in an attitude of natural flexion. Flexion of the fetal head on the trunk is increased during labour because the skull is attached to the fetal spine nearer the occiput than the sinciput. Pressure transmitted from the fundus of the uterus down the fetal spine will force the occiput lower than the sinciput, increasing flexion and resulting in the conversion of the suboccipitofrontal diameter of 10 cm to the favourable suboccipitobregmatic diameter of 9.5 cm.

Internal rotation of the head (Fig. 39.3)

As the leading part is driven onto the pelvic floor, the resistance of the muscular diaphragm and its gutter shape, sloping downwards anteriorly, cause the occiput to rotate forwards in the pelvis  th of a circle (45°) to lie under the symphysis pubis; the anteroposterior diameter of the head now lies in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis, which is the largest diameter. This causes a slight twist on the neck of the fetus so that the head is no longer aligned with the shoulders.

th of a circle (45°) to lie under the symphysis pubis; the anteroposterior diameter of the head now lies in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis, which is the largest diameter. This causes a slight twist on the neck of the fetus so that the head is no longer aligned with the shoulders.

th of a circle (45°) to lie under the symphysis pubis; the anteroposterior diameter of the head now lies in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis, which is the largest diameter. This causes a slight twist on the neck of the fetus so that the head is no longer aligned with the shoulders.

th of a circle (45°) to lie under the symphysis pubis; the anteroposterior diameter of the head now lies in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis, which is the largest diameter. This causes a slight twist on the neck of the fetus so that the head is no longer aligned with the shoulders.Crowning and extension of the head (Fig. 39.4)

The occiput escapes from beneath the subpubic arch and the smallest possible diameters, which are the suboccipitobregmatic diameter of 9.5 cm and the biparietal diameter of 9.5 cm, distend the vaginal orifice. This is termed ‘crowning’ and the head no longer retracts in between contractions. The head is now born by extension as it pivots on the suboccipital region around the pubic bone. The sinciput, face and chin sweep the perineum. The widest diameter to distend the vagina is the suboccipitofrontal 10 cm as the sinciput is born.

Internal rotation of the shoulders and external rotation of the head (Fig. 39.6)

The anterior shoulder is the first to reach the pelvic floor and this now rotates forward to lie under the symphysis pubis. This movement is accompanied by external rotation of the head  th of a circle (45°) more in the direction of restitution. The occiput now lies laterally, turned towards the woman’s thigh.

th of a circle (45°) more in the direction of restitution. The occiput now lies laterally, turned towards the woman’s thigh.

th of a circle (45°) more in the direction of restitution. The occiput now lies laterally, turned towards the woman’s thigh.

th of a circle (45°) more in the direction of restitution. The occiput now lies laterally, turned towards the woman’s thigh.Physiological changes

Edwards (1995) outlines the physiological principles which should underlie the management of the 2nd stage of labour. These include:

• Fetal hormone secretion aimed at adaptation to independent life.

• The condition of mother and baby.

• The bearing-down reflex.

• Thinning of the perineum.

• Position of the mother.

Management

The 2nd stage of labour begins when the cervix is fully dilated and ends when the fetus is fully expelled from the birth canal. Midwives and medical colleagues have used this definition to base the management of the delivery of the baby according to a time regime. This suggests that the exact timing of the 2nd stage of labour is possible. This concept has been challenged and it is probable that progress rather than an estimated time limit is more useful as an indicator of normality (Enkin et al 2000). At the end of the day the question must be asked about stages and phases of labour as to whether they are physiological entities or human imagination. Before describing the physiology and management of the 2nd stage, the concepts need to be examined.

The second stage of labour: two or three phases?

Crawford (1983) believed that the division of labour into three stages and subdividing the stages into phases was contrary to the actual events of labour and that basing the management of labour on these concepts could lead to distress and hazard for mother and fetus. While he discussed the division of the first stage of labour into the latent and active phase, he stated that the ‘distinction between the first and second stages leads to the greatest trouble in clinical practice’. He believed that the difficulty occurs because there is a lack of clear definition as to when the 2nd stage begins. If it begins with expulsive efforts by the woman, then some women wish to bear down before the cervix is fully dilated and sometimes a woman will not bear down until the presenting part is distending the perineum. Sometimes, if the woman has had epidural analgesia, she may not have an urge to bear down at all.

Aderhold & Roberts (1991) examined the concept of phases in the 2nd stage of labour with an in-depth study of four nulliparous women. They describe the above concepts of two phases to the 2nd stage as follows:

The early phase from complete dilation until the presenting part becomes visible which lasts 10 to 30 min and generally occurs with mild or no urge to bear down. Then the period of active bearing

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

th of a circle towards the side from which it started.

th of a circle towards the side from which it started.