Chapter 21 The role of pharmaceutical marketing

History of pharmaceutical marketing

There are not many accessible records of the types of marketing practised in the first known drugstore, which was opened by Arab pharmacists in Baghdad in 754, (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmaceutical_industry-cite_note-1) and the many more that were operating throughout the medieval Islamic world and eventually in medieval Europe. By the 19th century, many of the drug stores in Europe and North America had developed into larger pharmaceutical companies with large commercial functions. These companies produced a wide range of medicines and marketed them to doctors and pharmacists for use with their patients.

In the background, during the 19th century in the USA, there were the purveyors of tonics, salves and cure-alls, the travelling medicine shows. These salesmen specialized in selling sugared water or potions such as Hostetter’s Celebrated Stomach Bitters (with an alcoholic content of 44%, which undoubtedly contributed to its popularity). In the late 1800s, Joseph Myers, the first ‘snake oil’ marketer, from Pugnacity, Nebraska, visited some Indians harvesting their ‘medicine plant’, used as a tonic against venomous stings and bites. He took the plant, Echinacea purpurea, around the country and it turned out to be a powerful antidote to rattlesnake bites. However, most of this unregulated marketing was for ineffective and often dangerous ‘medicines’ (Figure 21.1).

The medical associations were unable to keep the doctors adequately informed about the vast array of new drugs. It fell, by default, upon the pharmaceutical industry to fill the knowledge gap. This rush of innovative medicines and promotion activity was named the ‘therapeutic jungle’ by Goodman and Gilman in their famous textbook (Goodman and Gilman, 1960). Studies in the 1950s revealed that physicians consistently rated pharmaceutical sales representatives as the most important source in learning about new drugs. The much valued ‘detail men’ enjoyed lengthy, in-depth discussions with physicians. They were seen as a valuable resource to the prescriber. This continued throughout the following decades.

A large increase in the number of drugs available necessitated appropriate education of physicians. Again, the industry gladly assumed this responsibility. In the USA, objections about the nature and quality of medical information that was being communicated using marketing tools (Podolsky and Greene, 2008) caused controversy in medical journals and Congress. The Kefauver–Harris Drug Control Act of 1962 imposed controls on the pharmaceutical industry that required that drug companies disclose to doctors the side effects of their products, allowed their products to be sold as generic drugs after having held the patent on them for a certain period of time, and obliged them to prove on demand that their products were, in fact, effective and safe. Senator Kefauver also focused attention on the form and content of general pharmaceutical marketing and the postgraduate pharmaceutical education of the nation’s physicians. A call from the American Medical Association (AMA) and the likes of Kefauver led to the establishment of formal Continued Medical Education (CME) programmes, to ensure physicians were kept objectively apprised of new development in medicines. Although the thrust of the change was to provide medical education to physicians from the medical community, the newly respectable CME process also attracted the interest and funding of the pharmaceutical industry. Over time the majority of CME around the world has been provided by the industry (Ferrer, 1975).

The marketing of medicines continued to grow strongly throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Marketing techniques, perceived as ‘excessive’ and ‘extravagant’, came to the attention of the committee chaired by Senator Edward Kennedy in the early 1990s. This resulted in increased regulation of industry’s marketing practices, much of it self-regulation (see Todd and Johnson, 1992); http://www.efpia.org/Content/Default.asp?PageID=296flags).

The size of pharmaceutical sales forces increased dramatically during the 1990s, as major pharmaceutical companies, following the dictum that ‘more is better’, bombarded doctors’ surgeries with its representatives. Seen as a competitive necessity, sales forces were increased to match or top the therapeutic competitor, increasing frequency of visits to physicians and widening coverage to all potential customers. This was also a period of great success in the discovery of many new ‘blockbuster’ products that addressed many unmet clinical needs. In many countries representatives were given targets to call on eight to 10 doctors per day, detailing three to four products in the same visit. In an average call on the doctor of less than 10 minutes, much of the information was delivered by rote with little time for interaction and assessment of the point of view of the customer. By the 2000s there was one representative for every six doctors. The time available for representatives to see an individual doctor plummeted and many practices refused to see representatives at all. With shorter time to spend with doctors, the calls were seen as less valuable to the physician. Information gathered in a 2004 survey by Harris Interactive and IMS Health (Nickum and Kelly, 2005) indicated that fewer than 40% of responding physicians felt the pharmaceutical industry was trustworthy. Often, they were inclined to mistrust promotion in general. They granted reps less time and many closed their doors completely, turning to alternative forms of promotion, such as e-detailing, peer-to-peer interaction, and the Internet.

Something had to give. Fewer ‘blockbusters’ were hitting the market, regulation was tightening its grip and the downturn in the global economy was putting pressure on public expenditure to cut costs. The size of the drug industry’s US sales force had declined by 10% to about 92 000 in 2009, from a peak of 102 000 in 2005 (Fierce Pharma, 2009). This picture was mirrored around the world’s pharmaceutical markets. ZS Associates, a sales strategy consulting firm, predicted another drop in the USA – this time of 20% – to as low as 70 000 by 2015. It is of interest, therefore, that the USA pharmaceutical giant Merck ran a pilot programme in 2008 under which regions cut sales staff by up to one-quarter and continued to deliver results similar to those in other, uncut regions. A critical cornerstone of the marketing of pharmaceuticals, the professional representative, is now under threat, at least in its former guise.

Product life cycle

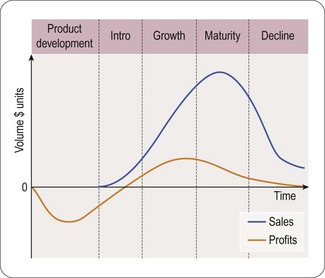

It is important to see the marketing process in the context of the complete product life cycle, from basic research to genericization at the end of the product patent. A typical product life cycle can be illustrated from discovery to decline as follows (William and McCarthy, 1997) (Figure 21.2).

The product’s life cycle period usually consists of five major steps or phases:

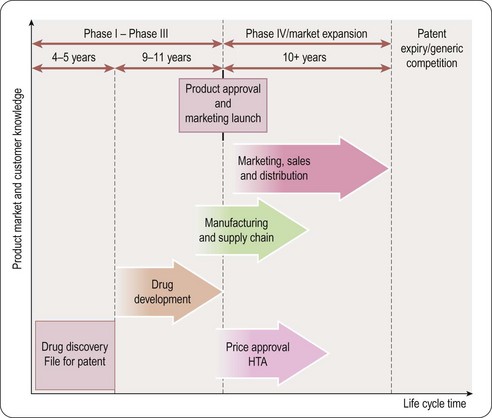

Pharmaceutical product life cycle (Figure 21.3)

As soon as a promising molecule is found, the company applies for patents (see Chapter 19). A patent gives the company intellectual property rights over the invention for around 20 years. This means that the company owns the idea and can legally stop other companies from profiting by copying it. Sales and profits will enable the manufacturer to reinvest in R&D:

• For a pharmaceutical product the majority of patent time could be over before the medicine even hits the market

• Once it is produced it takes some time for the medicine to build up sales and so achieve market share; in its early years the company needs to persuade doctors to prescribe and use the medicine

• Once the medicine has become established then it enters a period of maturity; this is the period when most profits are made

• Finally as the medicine loses patent protection, copies (generic products) enter the market at a lower cost; therefore, sales of the original medicine decline rapidly.

The duration and trend of product life cycles vary among different products and therapeutic classes. In an area of unmet clinical need, the entry of a new efficacious product can result in rapid uptake. Others, entering into a relatively mature market, will experience a slower uptake and more gradual growth later in the life cycle, especially if experience and further research results in newer indications for use (Grabowski et al., 2002).

Traditional Pharmaceutical marketing

Clinical studies

Pharmaceutical marketing depends on the results from clinical studies. These pre-marketing clinical trials are conducted in three phases before the product can be submitted to the medicines regulator for approval of its licence to be used to treat appropriate patients. The marketing planner or product manager will follow the development and results from these studies, interact with the R&D function and will develop plans accordingly. The three phases (described in detail in Chapter 17) are as follows.

Phase I trials are the first stage of testing in human subjects.

The product

Features, attributes, benefits, limitations (FABL)

• Early adopters/innovators: those who normally are quick to use a new product when it is available

• Majority: most fall into this category. There are the early majority and the late majority, defined by their relative speed of adoption. Some are already satisfied and have no need for a new product. Some wait for others to try first, preferring to wait until unforeseen problems arise and are resolved. Improved products (innovative therapies) may move this group to prescribe earlier

• Laggards/conservatives: this group is the slowest adopter, invariably waiting for others to gain the early experience. They wait for something compelling to occur, such as additional evidence to support the new product, or a new indication for which they do not currently have a suitable treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree