INTRODUCTION

The [first doctor] never asked me what I wanted. He did not mention my needs or treatment goals. He did not know—or seem to care—that my hope was to extend my quality time on this planet rather than merely linger. He did not care about the toll of the treatments on my body and my remaining days …

Thank goodness my [second doctor] was not like that specialist. Instead of ignoring my wishes and goals, my doctor was embracing them and keeping me as informed as possible. She’d discussed the diagnosis, prognosis, and possible treatments, and she’d asked me about how I wanted to proceed. Together, the two of us chose a treatment regimen that would slow tumor growth, while protecting what was precious to me: my quality of life. Too many other patients have doctors like that [first] specialist. A cancer-survivor friend told me that her oncologist once said, “I wish I could just treat the cancer; patients get in the way.” Another friend, with stage IV cancer, was advised by her oncologist to skip a three-hour car ride to visit her new granddaughter because she’d miss a chemo appointment— one that would do nothing to change the fatal nature of her advanced disease.

—Amy Berman, RN1

The gap between the way many patients wish healthcare decisions could be made and the way these decisions are actually made is tremendous. According to a 2014 survey conducted by the Altarum Institute, nearly all patients expect to be in control of medical decisions. Only 7% of adult, nonelderly patients wanted their physicians to be in the lead role.2 Despite this clear preference, the same survey found that the vast majority of patients let the doctor take charge of care decisions nonetheless.

Among the many complex factors that go into medical decision making, there is a widespread perception that the values of patients often get pushed to the bottom. Patient experience (a term that is increasingly replacing the more narrow term patient satisfaction) is a core component of delivering value-based care. As we have mentioned many times in this book, defining value as a ratio of physical outcomes to costs is too simplistic. At the end of the day, care that improves some health outcomes while ignoring a patient’s treatment goals or putting her through a miserable experience may not be worth it. And yet, meaningfully involving patients in our decisions is a goal that continues to frequently evade our profession.

There are surely many reasons for this, but Dr Alvan Feinstein, a Yale physician credited with helping to start the field of clinical epidemiology, hit the nail on the head when he pointed out the great irony of what clinicians often consider “hard” vs “soft” data: “A doctor’s observation of whether the patient has tenderness in a knee is regarded as objective and is therefore ‘harder’ than the patient’s report of the pain experienced when he walks.”3 These words may ring as true in 2014 as they did in the early 1960s when they were first articulated. In the clinical world, directly observed data continues to take precedence over more subjective, but equally important reports of patient experience.

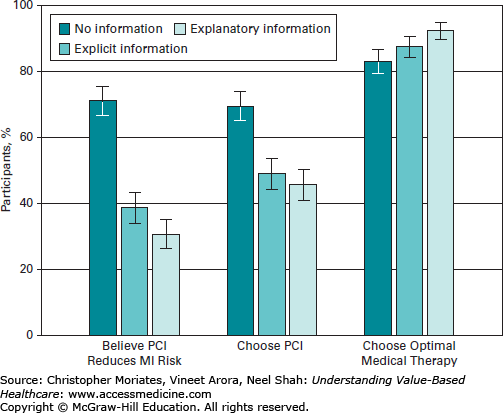

As online health information empowers patients to make informed choices, the paternalistic clinician-patient relationship that was once widely accepted is being increasingly called into question, and in many cases is falling away entirely toward a more collaborative relationship (Table 12-1). Clearly, the best care results when informed patients and knowledgeable clinicians work together and are on the same page. A recent study demonstrated that there is a significant difference between merely telling patients information explicitly, and actually explaining clinical reasoning. Many patients mistakenly believe that a procedure called percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) will prevent a myocardial infarction (MI or “heart attack”). Researchers at the Cleveland Clinic and the University of Michigan tested patients beliefs after they received “no information,” “explicit information” (simply told that PCI does not prevent MI), and “explanatory information” (detailed explanation of why PCI does not prevent MI).4 Perhaps, not surprisingly, patients who received explanatory information were significantly less likely to choose PCI and significantly more likely to instead choose a more optimal medical therapy for their care (Figure 12-1).

Patient-physician interactions

| Model for Patient-Physician Interaction | Physicians’ Role | Patients’ Role | Knowledge “Flow” | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paternalistic | Directive | Passive | One-way knowledge transfer (physician to patient) | Compliance of patient to physicians’ directive |

| Autonomous | Receptive | Directive | One-way knowledge transfer (patient to physician) | Compliance of physician to patients’ directive |

| Shared decision making | Informative | Informative | Two-way knowledge exchange | Equity in the decision making process |

| Collaborative decision making | Supportive | Proactive | Knowledge building that goes beyond clinical issues (Shared learning by exchanging information) | Optimal action plan to improve health |

Figure 12-1

Patient beliefs concerning percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and medication. (Reproduced, with permission, from Rothberg MB, Scherer L, Kashef MA, et al. The effect of information presentation on beliefs about the benefits of elective percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1623-1629. Copyright © 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.)

In this chapter, we describe efforts to enable better “shared decision making” and discuss what the rise of the empowered “e-patient” may mean for modern healthcare delivery. We briefly review the promise and pitfalls of consumer-directed health plans. Lastly, we examine emerging efforts to better measure and report patient experiences, both to inform value-based care and to create necessary accountability.

SHARED DECISION MAKING

The term “shared decision making” (SDM) has been used for decades, though not everyone who invokes this term is talking about the same thing. SDM was first introduced into the clinical lexicon by the 1982 President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research.5 As it turns out, since that time there have been at least 342 articles published on SDM, many of them using different definitions. Most notably, the concepts of patient values and options appeared in only half of the definitions. Dartmouth Professor Glyn Elwyn and his colleagues nicely sum up the modern intention of SDM thusly: “an approach where clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of making decisions, and where patients are supported to consider options, to achieve informed preferences.”6

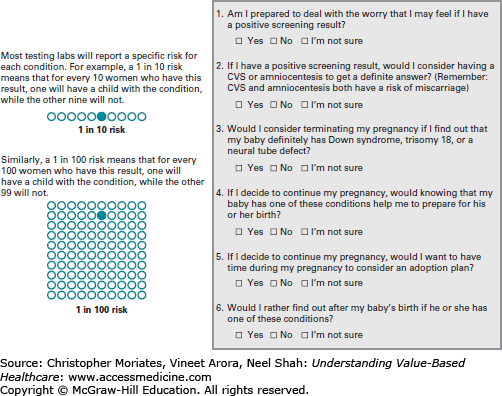

One way to promote SDM is through the use of tools called “decision aids,” which can be used by patients to communicate to clinicians about their preferences for treatment options. Decision aids come in many complementary formats, including by paper, web, or video.7 Some clinicians utilize multiple formats at once. A routine use of SDM is to guide expectant mothers on the use of prenatal screening tests that can uncover genetic problems such as Down syndrome before a baby is born. Some mothers would prefer to avoid testing since few interventions are available other than pregnancy termination. Other mothers absolutely feel that they need to know. And some are unsure whether they want to know or not. Complicating matters, the information from these tests (like all tests) can be equivocal or imprecise. The Dartmouth Center for Shared Decision Making helps guide patients through these and other challenging, “preference-sensitive” decisions (see Chapter 7) using an online video and companion booklet. The booklet contains a visual aid to help communicate risk and a questionnaire to help patients articulate their preferences (Figure 12-2). The Dartmouth Center maintains a large library of decision aids on over 30 topics.8 A 2009 Cochrane review of these types of decision aids concluded that decision aids can lead to improved knowledge, more accurate perceptions of risk, decisions more consistent with patients’ values, reduced internal conflict for patients, and fewer undecided patients.9

The design of the decision aid is critically important. Visual representations such as icon arrays and bar graphs seem to be most effective for conveying statistical information to patients.10 The type of statistics to include also requires careful thought—presenting absolute risk reductions is far better than reporting relative risk reductions, and some statistics such as “number needed to treat” seem to overly confuse patients and may undermine the utility of the decision aid.10

Studies of SDM interventions have demonstrated improved care, including greater patient satisfaction.11 A randomized controlled trial recently published in Health Affairs compared patients who received enhanced support (phone coaching with decision aids) during decision making for preference-sensitive decisions to those who did not. SDM resulted in lower overall medical costs, lower hospital admissions, and fewer preference-sensitive surgeries than patients who received usual care.12 The introduction of a decision aid for hip and knee osteoarthritis at Group Health Cooperative (a nonprofit health system in Seattle, Washington) was associated with lower costs (12%-21%), largely due to fewer patients opting to undergo surgery once they were fully informed about the trade-offs.13 Based on these and other emerging studies, it has been estimated that use of SDM for just 11 procedures nationwide could save $9 billion in 10 years.14

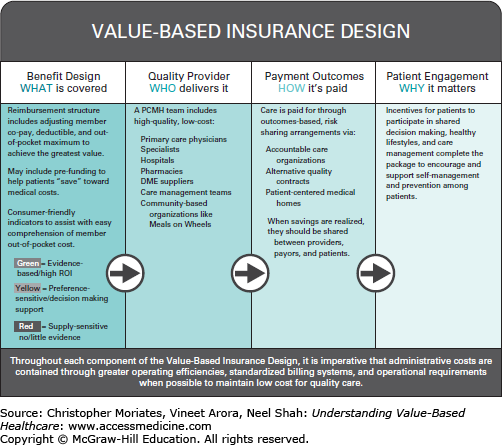

Given the promise of SDM to improve value, the Maine Health Management Coalition (a multi-stakeholder collaborative led by big employers and other large healthcare “purchasers”) has proposed placing healthcare services into three tiers according to a traffic stoplight scheme: “green” services are evidence-based with a high healthcare return on investment, “yellow” services are preference-sensitive and require decision support (perhaps in the form of an SDM tool), and “red” services are supply-sensitive with little or no evidence to support their use (Figure 12-3). Yellow services are actively paired with decision aids, often embedded directly into the electronic medical record or the clinician’s order-entry system, and integrated into value-based health insurance benefit designs. As a result, SDM is now a major component of an ambitious plan to reduce healthcare costs while improving value in the state of Maine.

Although purchasers and other stakeholders have great interest in SDM, clinicians are often concerned about the extra work it can involve. Few of us are clamoring for more to do. In fact, a systematic review demonstrated that the most common barrier to adoption of SDM was time constraints.15 Some decision aids are also obviously better than others—in the same study clinicians cited a lack of applicability due to characteristics of either the patient or the clinical situation. Despite the benefits to patients, these barriers are considerable and not easy to surmount. A 2010 Cochrane review found little evidence of effective ways to engage clinicians to adopt SDM and noted that further study of SDM is warranted.16

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) encourages greater use of SDM in healthcare. According to Section 3506 of the ACA, an independent entity to develop standards and certify patient decision aids will be funded. In addition, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation has been authorized to evaluate models of SDM on relevant outcomes.14 Furthermore, the ACA authorized the creation of the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), which enables funding of research related to SDM involving patient stakeholders as part of its patient-centered research priorities.17

HISTORY OF THE E-PATIENT MOVEMENT

While SDM represents one way to bridge the gap between patient preferences and clinical decisions, the rise of the e-patient movement represents a parallel trend toward greater patient involvement in decisions regarding care. Although it is often assumed that “e-patients” refer to patients who access healthcare information electronically, the term was originally coined by physician author Tom Ferguson in reference to patients who are “equipped, enabled, empowered and engaged in their health and health care decisions.”18 His initial efforts led to the formation of the Society of Participatory Medicine, which is a professional organization that many e-patients are affiliated with. In addition to the characteristics outlined by Ferguson, a recent study of e-patients identified two more qualities19:

Evaluating: Evaluating encompasses how e-patients find information, and critically assess the source of that information (ie, Web page vs healthcare professional), determining which sources are most trustworthy based on their assessment.

Equal:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree