Chapter 1

The Past and the Present

Things are more like they are now than they ever were before.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

The future is like the present – only longer.

Goose Gossage

The Inaccuracy of Forecasting

Predicting the future is difficult. A historical look at forecasting over time suggests that we have continually tried to predict the future … and have continually failed to do so with any accuracy. Figure 1.1 indicates the four major challenges when trying to predict the future.

Predicting the future is quite difficult and forecasting accuracy generally is challenged by uncertainties around key assumptions. This text will highlight ways in which this uncertainty can be turned into a positive factor – informing decision makers about uncertainty to increase their awareness in their decision making. Forecasts always contain bias. Sometimes this is the result of data collection methodologies, sometimes it is contributed by the depth of conviction of key opinion leaders, and sometimes it is simply the result of a loud, vocalized stance. Bias is inevitable, but hidden bias is the bane of the forecaster … and contributes to sub-optimal decision making.

Figure 1.1 The challenges of forecasting

The balance between ‘too general’ and ‘too detailed’ is difficult to define a priori. An example of a ‘too general’ forecast is one that is a simple spreadsheet where patients are first multiplied by share and then by price per therapy to generate revenue. This is a valid forecast algorithm, but once more subtle questions are asked – such as, are there different patient segments, how is share constructed, and what is the compliance rate – the forecast loses its utility. At the other end of the spectrum are forecasts that are ‘too detailed.’ These forecasts tend to take the form of complex algorithms and multi-paged spreadsheets with many formulae. This also is a valid forecast algorithm, but the transparency and transferability of the forecast itself becomes quite low.

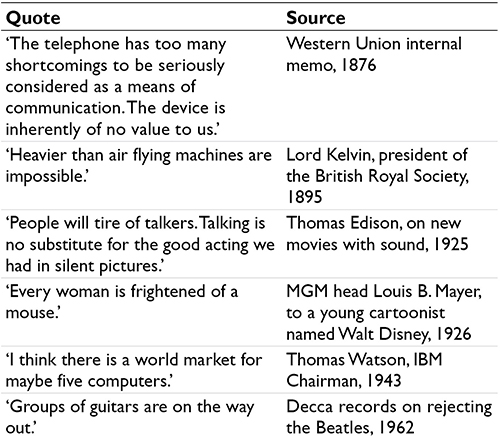

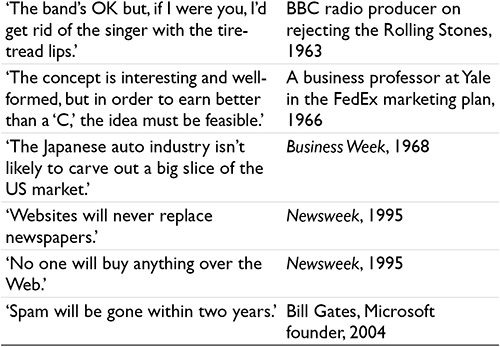

In this text we will address these four main challenges to forecasting. First, we will transform the uncertainty in forecasting into a perspective that enables more informed decisions. We will tackle bias head on, identifying the most prevalent sources of bias in pharmaceutical forecasting and suggesting methods for control of bias factors. The final challenge – balance between ‘too general’ and ‘too detailed’ – is a function of corporate culture and what is acceptable within an organization. This text will, however, examine the characteristics of each extreme and suggest approaches to balanced forecasting. Table 1.1 presents some forecasts by ‘thought leaders’ in their respective fields.

Table 1.1 Even the experts get it wrong sometimes

Sources: O’Boyle, J. (1999), Wrong!: The Biggest Mistakes and Miscalculations Ever Made by People Who Should Have Known Better, New York: Penguin Putnam, Inc.; Also, see http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Incorrect_predictions [accessed 15 December 2015].

A more subtle – and just as important – lesson is to reflect upon the pressures that must have existed on the forecaster in industries associated with the individuals who made these statements. If I am a forecaster for personal computers and the chairman of IBM has made a public statement that he believes the world market for computers is five, chances are that I will be affected by this statement in my view of the future. We will discuss the issue of bias in forecasting in each of the subsequent chapters.

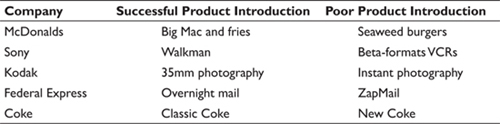

Are companies any better at forecasting than individual experts? The results in Table 1.2 suggest that companies also have a mixed record when it comes to forecasting. Table 1.2 presents some new products that have been introduced by large companies and categorizes the products as ‘leaders’ and ‘laggards’ with respect to their relative success in the global markets. These companies all have successful new product launches to their credit, but also introduced products to the market with limited success. It is reasonable to assume that the planning for the new products included forecasts that presumably justified the product launches. What went wrong? We will explore the answer to this question when we discuss new product forecasting in Chapter 3.

Table 1.2 The success of new product introductions

Forecasting in the Pharmaceutical Industry

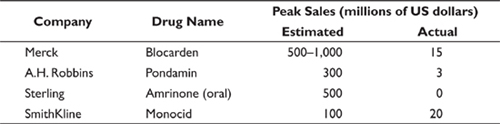

What about examples from the pharmaceutical industry? In 1985 there was an article published in Pharmaceutical Executive that examined the linkage between successful new product launches and a company’s stock price. The authors stated that ‘Projections of the sales of new drugs, especially of blockbuster drugs, have almost always been too high. Investors have been burned so many times with this game that it is difficult to understand why they continue to play it.’1 In support of this statement have a look at the data in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3 Blockbusters that went bust

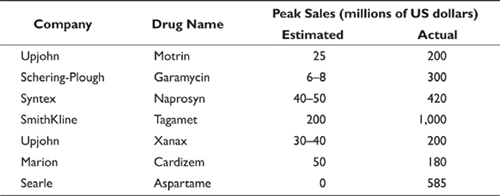

At the other end of the scale are products that achieved forecasts beyond their initial expectations (see Table 1.4). These examples are offered as evidence that some blockbuster drugs are not recognized as such when initially forecast.

The data in Tables 1.3 and 1.4 are those cited in the 1985 article in Pharmaceutical Executive

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree