(1)

Department of Histopathology and Cytology, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, UK

Abstract

In this chapter the anatomy and appearance of the normal cervix in histology and cytology specimens will be described with particular emphasis on glandular tissue.

Keywords

CervixEndocervixSquamocolumnar junctionSquamous metaplasiaTransformation zoneMetaplasiaStructure and Development

The cervix is a fibromuscular organ, 3–4 cm in length and approximately 2.5 cm in diameter, lined and covered on the outer aspect by epithelium. It forms the inferior part of the uterus and projects into the vagina. Anatomically it is divided into the portio vaginalis which is that part which projects into the vagina and the supravaginal portion. It is continuous above with the body of the uterus at the uterine isthmus where there is a fibromuscular junction, the internal os, separating the fibromuscular tissue of the cervix from the muscular tissue of the body of the uterus.

The passage between the uterine cavity and the vagina is via the endocervical canal, which is continuous with the endometrial cavity above at the level of the internal os and the vagina below at the external os. The portion of the cervix lying exterior to the external os and in continuity with the vagina is called the ectocervix. The endocervical canal is approximately 3 cm long, fusiform in shape, and flattened from front to back. It measures between 6 and 8 mm in width at the widest point but cyclical changes result in alterations in the dimensions of the canal, in tissue vascularity and in the quantity and biophysical characteristics of mucus secreted by endocervical cells [1, 2]. Mucus secretion with increased vascularity, congestion and stromal oedema predominate during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle and reach a peak at ovulation in order to provide an ideal environment for the passage of spermatozoa.

The cervix varies in size and shape depending on a woman’s age, parity and hormonal status. In nulliparous women it is barrel-shaped with a small circular external os but it changes shape and size during pregnancy and during delivery and labour, such that the multiparous cervix is larger than that found in nulliparous women and the external os appears as a wide, gaping transverse slit.

Cervical Epithelium

The cervix is covered by both stratified non-keratinising squamous epithelium and columnar mucin secreting epithelium and these two types of epithelium meet at the squamocolumnar junction.

Squamous Epithelium

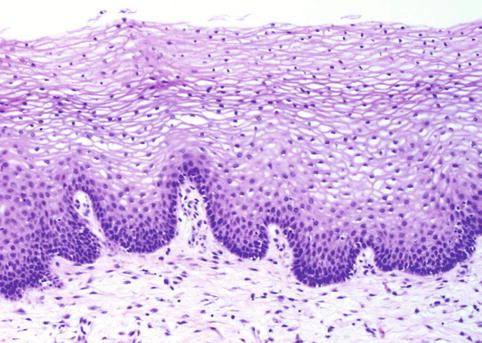

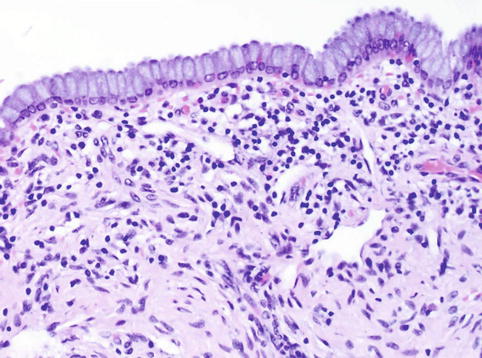

The ectocervix is covered by stratified non-keratinising glycogen-containing squamous epithelium. Histologically this epithelium is composed of a basal layer, a parabasal layer, an intermediate cell layer and a superficial cell layer (See Fig. 1.1). It is separated from the underlying cervical stroma by a basement membrane and the epithelial-stromal junction is usually linear but sometimes slightly undulating with short projections of stroma at regular intervals called stromal papillae.

Fig. 1.1

Normal squamous mucosa of the ectocervix

In haematoxylin and eosin stained histological sections basal layer epithelium consists of a single row of small cylindrical cells with relatively large ovoid nuclei and sparse eosinophilic cytoplasm. In normal cervical squamous epithelium the basal layer nuclei maintain a regular perpendicular orientation to the basement membrane. Growth and replacement of the squamous epithelium occurs from the basal layer and therefore nucleoli, numerous chromocentres and mitoses are identified in this layer.

The parabasal cell layer is composed of two or more layers of polyhedral cells with relatively large nuclei and distinct intercellular bridges. Mitoses may be found in this layer particularly in basal hyperplasia in response to chronic infection or trauma.

The intermediate cell layer is composed of polygonal cells with abundant glycogen rich, frequently vacuolated, cytoplasm and small nuclei.

The superficial cell layer is composed of similar cells to those in the intermediate cell layer except that the cells are flattened with even smaller nuclei and evident keratinisation.

Glycogenation of the intermediate and superficial layers is a sign of normal maturation under the influence of oestrogen. In the absence of oestrogen normal maturation does not occur and therefore after the menopause the squamous epithelium of the cervix does not mature beyond the parabasal layer and the epithelium is thin and atrophic.

Columnar Mucin Secreting Epithelium

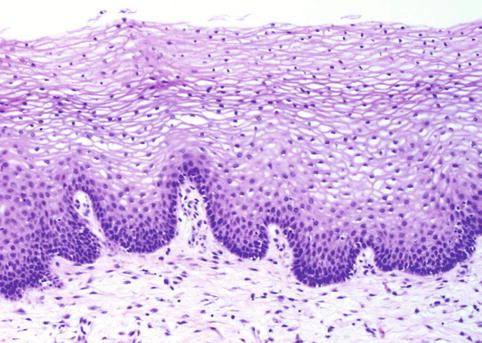

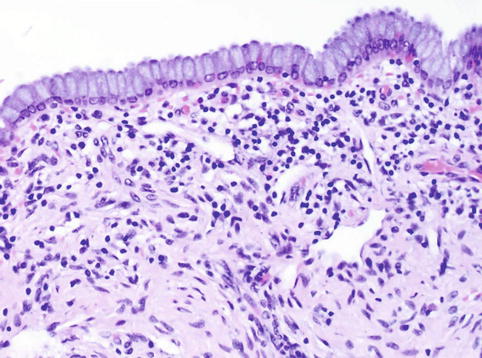

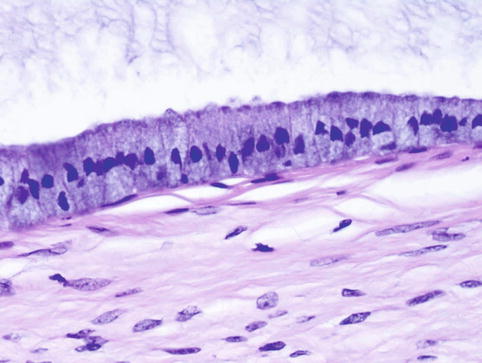

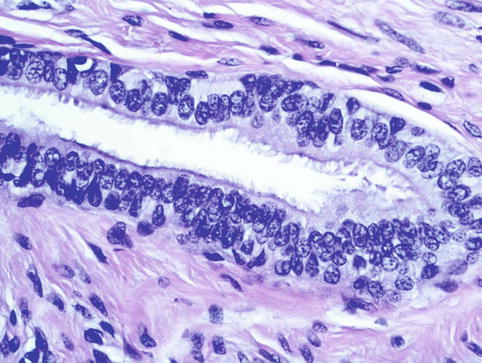

The endocervical canal is lined by columnar epithelium composed of a single layer of tall slender cells with abundant cytoplasm and basal situated round or ovoid nuclei (See Fig. 1.2). The nuclei are usually situated in the basal part of the cell but may lie suprabasally or in the middle of the cell during active mucus secretion (See Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.2

Normal columnar glandular mucosa of the endocervix

Fig. 1.3

Columnar epithelium of the endocervix with evidence of active secretion. Note the displaced nuclei and intracellular mucin accumulation

There are two types of columnar epithelial cell: non-ciliated secretory cells and ciliated cells.

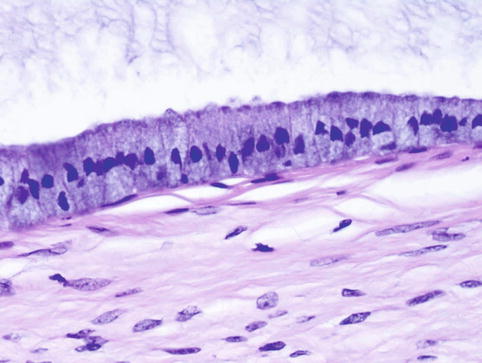

The secretory cells predominate in the columnar epithelium and utilise both apocrine and merocrine secretion to produce both acid and neutral mucin, although the relative amounts vary with the menstrual cycle [3]. The ciliated cells are covered with tiny kinocilia that beat rhythmically towards the cervical canal and vagina. The distribution of the ciliated cells is not uniform in that they are found in highest concentration in the upper endocervical canal close to the endometrial junction and rarely seen close to the squamocolumnar junction (See Fig. 1.4).

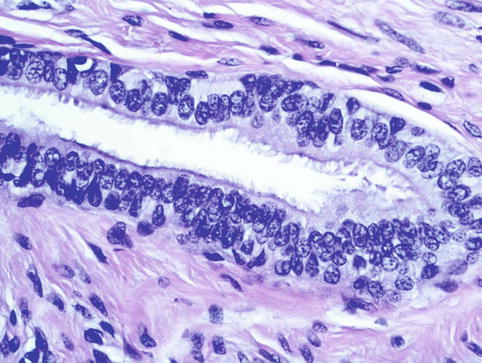

Fig. 1.4

Ciliated columnar cells lining an endocervical crypt in the upper endocervix

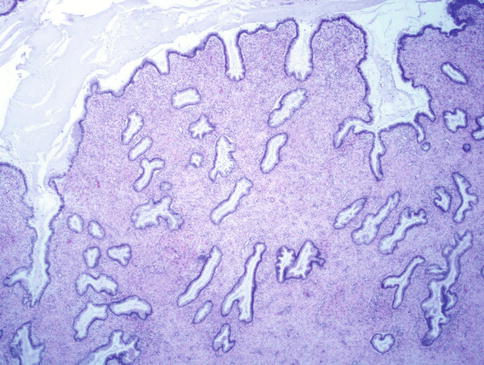

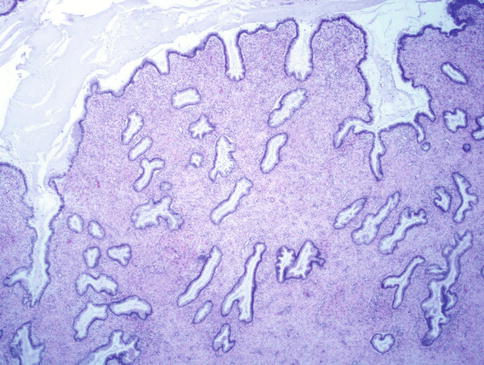

The columnar epithelium does not form a single layer of cells lining the endocervical canal. Histological (two-dimensional) examination suggests that the endocervical canal is formed of numerous glands lined by columnar epithelium but elegant three-dimensional reconstruction has shown that these apparent glands are in fact a manifestation of an extensive cleft like system whereby there are numerous complex infoldings of endocervical epithelium on stroma to form endocervical folds and crypts [4, 5]. The crypts may extend to a depth of nearly 8 mm from the surface of the endocervical canal and these architectural features may be valuable in the diagnosis of invasive neoplastic lesions of the endocervix (see Chap. 5) (See Fig. 1.5) [6, 7].

Fig. 1.5

Low power photomicrograph of the endocervix showing the complex crypt architecture

Squamocolumnar Junction

The location of the junction between the columnar epithelium of the endocervix and the squamous epithelium of the ectocervix in relation to the external os varies over a woman’s lifetime and is dependent on hormonal influences, oral contraceptive use and physiological conditions such as pregnancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree