Chapter 2 The nature of disease and the purpose of therapy

Concepts of disease

The practice of medicine predates by thousands of years the science of medicine, and the application of ‘therapeutic’ procedures by professionals similarly predates any scientific understanding of how the human body works, or what happens when it goes wrong. As discussed in Chapter 1, the ancients defined disease not only in very different terms, but also on a quite different basis from what we would recognize today. The origin of disease and the measures needed to counter it were generally seen as manifestations of divine will and retribution, rather than of physical malfunction. The scientific revolution in medicine, which began in earnest during the 19th century and has been steadily accelerating since, has changed our concept of disease quite drastically, and continues to challenge it, raising new ethical problems and thorny discussions of principle. For the centuries of prescientific medicine, codes of practice based on honesty, integrity and professional relationships were quite sufficient: as therapeutic interventions were ineffective anyway, it mattered little to what situations they were applied. Now, quite suddenly, the language of disease has changed and interventions have become effective; not surprisingly, we have to revise our ideas about what constitutes disease, and how medical intervention should be used. In this chapter, we will try to define the scope and purpose of therapeutics in the context of modern biology. In reality, however, those in the science-based drug discovery business have to recognize the strong atavistic leanings of many healthcare professions1, whose roots go back much further than the age of science.

Therapeutic intervention, including the medical use of drugs, aims to prevent, cure or alleviate disease states. The question of exactly what we mean by disease, and how we distinguish disease from other kinds of human affliction and dysfunction, is of more than academic importance, because policy and practice with respect to healthcare provision depend on where we draw the line between what is an appropriate target for therapeutic intervention and what is not. The issue concerns not only doctors, who have to decide every day what kind of complaints warrant treatment, the patients who receive the treatment and all those involved in the healthcare business – including, of course, the pharmaceutical industry. Much has been written on the difficult question of how to define health and disease, and what demarcates a proper target for therapeutic intervention (Reznek, 1987; Caplan, 1993; Caplan et al., 2004); nevertheless, the waters remain distinctly murky.

What is health?

We also find health defined in functional terms, less idealistically than in the WHO’s formulation: ‘…health consists in our functioning in conformity with our natural design with respect to survival and reproduction, as determined by natural selection…’ (Caplan, 1993). Here the implication is that evolution has brought us to an optimal – or at least an acceptable – compromise with our environment, with the corollary that healthcare measures should properly be directed at restoring this level of functionality in individuals who have lost some important element of it. This has a fashionably ‘greenish’ tinge, and seems more realistic than the WHO’s chillingly utopian vision, but there are still difficulties in trying to use it as a guide to the proper application of therapeutics. Environments differ. A black-skinned person is at a disadvantage in sunless climates, where he may suffer from vitamin D deficiency, whereas a white-skinned person is liable to develop skin cancer in the tropics. The possession of a genetic abnormality of haemoglobin, known as sickle-cell trait, is advantageous in its heterozygous form in the tropics, as it confers resistance to malaria, whereas homozygous individuals suffer from a severe form of haemolytic anaemia (sickle-cell disease). Hyperactivity in children could have survival value in less developed societies, whereas in Western countries it disrupts families and compromises education. Obsessionality and compulsive behaviour are quite normal in early motherhood, and may serve a good biological purpose, but in other walks of life can be a severe handicap, warranting medical treatment.

Health cannot, therefore, be regarded as a definable state – a fixed point on the map, representing a destination that all are seeking to reach. Rather, it seems to be a continuum, through which we can move in either direction, becoming more or less well adapted for survival in our particular environment. Perhaps the best current definition is that given by Bircher (2005) who states that ‘health is a dynamic state of wellbeing characterized by physical, mental and social potential which satisfies the demands of life commensurate with age, culture and personal responsibility’. Although we could argue that the aim of healthcare measures is simply to improve our state of adaptation to our present environment, this is obviously too broad. Other factors than health – for example wealth, education, peace, and the avoidance of famine – are at least as important, but lie outside the domain of medicine. What actually demarcates the work of doctors and healthcare workers from that of other caring professionals – all of whom may contribute to health in different ways – is that the former focus on disease.

What is disease?

Consider the following definitions of disease:

• A condition which alters or interferes with the normal state of an organism and is usually characterized by the abnormal functioning of one or more of the host’s systems, parts or organs (Churchill’s Medical Dictionary, 1989).

• A morbid entity characterized usually by at least two of these criteria: recognized aetiologic agents, identifiable groups of signs and symptoms, or consistent anatomical alterations (elsewhere, ‘morbid’ is defined as diseased or pathologic) (Stedman’s Medical Dictionary, 1990).

• ‘Potential insufficient to satisfy the demands of life’ as outlined by Bircher (2005) in his definition of health above.

Harm and disvalue – the normative view

A definition of disease which tries to combine the concepts of biological malfunction and harm (or disvalue) was proposed by Caplan et al. (1981):

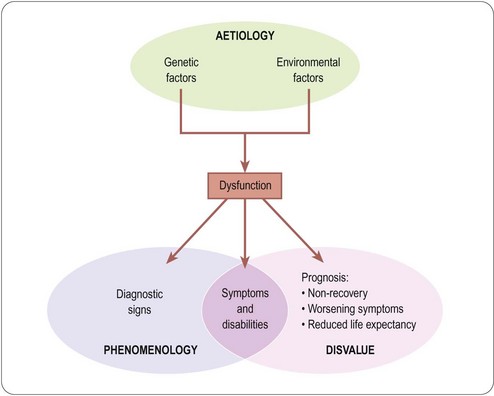

In conclusion, disease proves extremely difficult to define (Scully, 2004). The closest we can get at present to an operational definition of disease rests on a combination of three factors: phenomenology, aetiology and disvalue, as summarized in Figure 2.1.

Labelling human afflictions as diseases (i.e. ‘medicalizing’ them) has various beneficial and adverse consequences, both for the affected individuals and for healthcare providers. It is of particular relevance to the pharmaceutical industry, which stands to benefit from the labelling of borderline conditions as diseases meriting therapeutic intervention. Strong criticism has been levelled at the pharmaceutical industry for the way in which it uses its resources to promote the recognition of questionable disorders, such as female sexual dysfunction or social phobia, as diseases, and to elevate identified risk factors – asymptomatic in themselves but increasing the likelihood of disease occurring later – to the level of diseases in their own right. A pertinent polemic (Moynihan et al., 2004) starts with the sentence: ‘there’s a lot of money to be made from telling healthy people they’re sick’, and emphasizes the thin line that divides medical education from marketing (see Chapter 21).

The aims of therapeutics

Components of disvalue

The discussion so far leads us to the proposition that the proper aim of therapeutic intervention is to minimize the disvalue associated with disease. The concept of disvalue is, therefore, central, and we need to consider what comprises it. The disvalue experienced by a sick individual has two distinct components2 (Figure 2.1), namely present symptoms and disabilities (collectively termed morbidity), and future prognosis (namely the likelihood of increasing morbidity, or premature death). An individual who is suffering no abnormal symptoms or disabilities, and whose prognosis is that of an average individual of the same age, we call ‘healthy’. An individual with a bad cold or a sprained ankle has symptoms and disabilities, but probably has a normal prognosis. An individual with asymptomatic lung cancer or hypertension has no symptoms but a poor prognosis. Either case constitutes disease, and warrants therapeutic intervention. Very commonly, both components of disvalue are present and both need to be addressed with therapeutic measures – different measures may be needed to alleviate morbidity and to improve prognosis. Of course, such measures need not be confined to physical and pharmacological approaches.

Therapeutic intervention is not restricted to treatment or prevention of disease

It is obvious that departures from normality can bring benefit as well as disadvantage. Individuals with above-average IQs, physical fitness, ball-game skills, artistic talents, physical beauty or charming personalities have an advantage in life. Is it, then, a proper role of the healthcare system to try to enhance these qualities in the average person? Our instinct says not, because the average person cannot be said to be diseased or suffering. There may be value in being a talented footballer, but there is no harm in not being one. Indeed, the value of the special talent lies precisely in the fact that most of us do not possess it. Nevertheless, a magical drug that would turn anyone into a brilliant footballer would certainly sell extremely well; at least until footballing skills became so commonplace that they no longer had any value3.

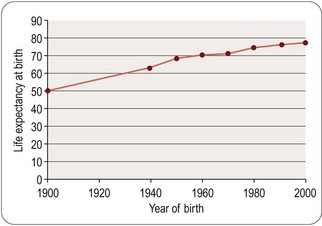

Football skills may be a fanciful example; longevity is another matter. The ‘normal’ human lifespan varies enormously in different countries, and in the West it has increased dramatically during our own lifetime (Figure 2.2). Is lifespan prolongation a legitimate therapeutic aim? Our instinct – and certainly medical tradition – suggests that delaying premature death from disease is one of the most important functions of healthcare, but we are very ambivalent when it comes to prolonging life in the aged. Our ambivalence stems from the fact that the aged are often irremediably infirm, not merely chronologically old. In the future we may understand better why humans become infirm, and hence more vulnerable to the environmental and genetic circumstances that cause them to become ill and die. And beyond that we may discover how to retard or prevent aging, so that the ‘normal’ lifespan will be much prolonged. Opinions will differ as to whether this will be the ultimate triumph of medical science or the ultimate social disaster4. A particular consequence of improved survival into old age is an increased incidence of dementia in the population. It is estimated that some 700 000 people in the UK have dementia and world wide prevalence is thought to be over 24 million. The likelihood of developing dementia becomes greater with age and 1.3% of people in the UK between 65 and 69 suffer from dementia, rising to 20% of those over 85. In the UK alone it has been forecast that the number of individuals with dementia could reach 1.7 million by 2051 (Nuffield Council on Bioethics, 2009).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree