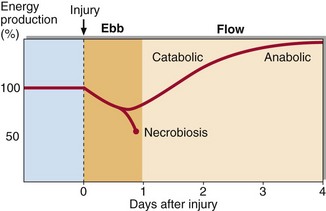

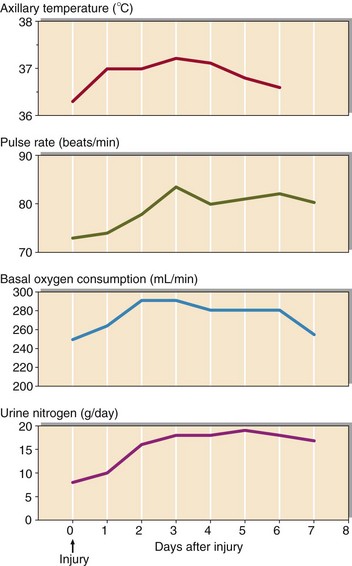

55 The problems faced by the traumatized individual are listed in Table 55.1. The metabolic response to injury (Fig 55.1) can be thought of as a protective physiological response designed to keep the individual alive until healing processes repair the damage that has been done. It is mediated by a complex series of neuroendocrine and cellular processes, all of which contribute to the overall goal – survival. The metabolic response to injury becomes clinically important only when the degree of injury is severe. Fig 55.1 The changes in body temperature, pulse rate, oxygen consumption and urinary nitrogen excretion which accompany injury. The metabolic response to injury has two phases, the ebb and the flow (Fig 55.2). The ebb phase is usually short and may correspond to clinical shock, resulting from reduced tissue perfusion. The physiological changes that occur here are designed to restore adequate vascular volume and maintain essential tissue perfusion. The severity of the ebb phase determines clinical outcome. If the ebb phase is mild or moderate, patients will have an uncomplicated transition to the flow phase. However, if severe, patients may develop the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). The features of this are shown in Table 55.2. This is a complex pathophysiological state involving a vast array of inflammatory mediators and hormonal regulators, but the underlying mechanisms have yet to be clarified. No therapeutic strategies have been found to be helpful, perhaps because of our incomplete understanding of the SIRS. However, a proportion of patients will recover with intensive life support, including ventilation and dialysis.

The metabolic response to injury

The phases of the metabolic response to injury

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine