FIGURE 2.1 Example of a computerized prescriber order entry (CPOE) system.

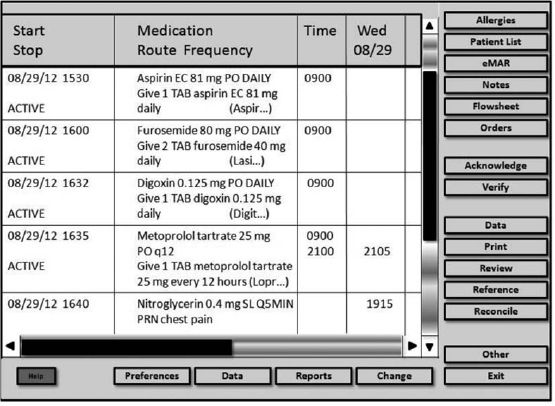

In addition to maintaining the patient’s permanent record, inpatient systems may record medications as they are administered to the patient, thereby maintaining an interactive patient eMAR. Figure 2.3 presents a screenshot of a sample eMAR. In the outpatient setting, similar technologies can facilitate sharing of patient and electronic transfers of medication prescription requests. For example, prescription requests, along with supportive data, may be transferred electronically to a pharmacy. Limitations to implementation of such software in healthcare institutions tend to include cost, workflow support, training, and organizational factors.5 Paper-based records should offer the same data recorded as the electronic medical record.

Patients are permitted to receive copies of their medical records, but the procedures for this must be set forth by the healthcare institution in accordance with state and federal law. Typically, patients can review their medical record in the medical records department of the institution or receive results of laboratory and diagnostic testing from their physician.3

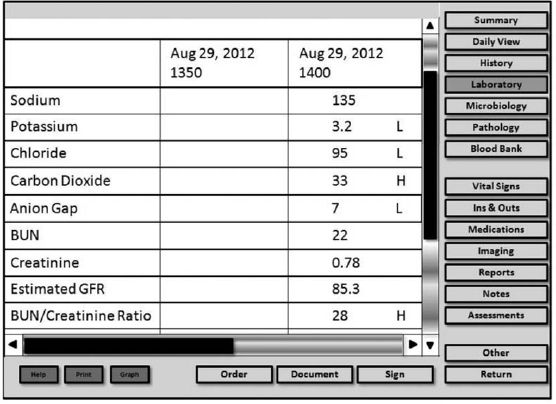

FIGURE 2.2 Example of laboratory data stored in an electronic system.

Pharmacists can follow a number of steps to prevent improper disclosure of medical information, thereby preventing legal consequences and fines:

• Providers should keep clipboards and folders containing patient information with them at all times and/or in a secure area (e.g., in a locked file in the pharmacy department).

• Providers should follow the institution’s policies for retaining and discarding health information. This may involve storage of information in locked cabinets and shredding materials when they are no longer needed.

• Providers should sign off of the computer system when they are finished using it. Applications with patient information should never be left open, even if the provider just gets up for a minute to answer a phone or to use the restroom.

FIGURE 2.3 Example of an electronic medication administration record (eMAR).

SYSTEMATIC APPROACH TO DATA COLLECTION

Considering the often large amount of data available in the patient’s medical record, pharmacists must use a systematic approach to review patient data. This process involves reviewing pertinent and timely components of the patient’s medical record, the MAR, and other relevant data, and then compiling this data. Data may be transcribed onto a written or electronic data collection form and can be used by the pharmacist to maintain an accurate, consistent, and organized view of the patient for the purposes of developing a focused pharmacy-related assessment and plan of care.

Data are often streamlined to make it easier to provide pharmaceutical care to the patient; however, the data must be comprehensive enough to ensure that the pharmacist maintains a complete understanding of the patient. Data may be focused on a single visit in the outpatient or urgent care setting or on a single day or visit during an inpatient hospital stay and then updated daily. A systematic data collection process can help the pharmacist stay organized from patient to patient, day to day.

Data collection methods may vary between pharmacists or clinical sites; however, they share the common goal of allowing a consistent review of a single patient or multiple patients at once. This approach usually involves the use of a paper-based or electronic form that has enough space to include all of the relevant material that the pharmacist may need to collect. These forms are often developed or tailored to meet the needs of a specific pharmacist with a designated set of patient care responsibilities and may be formatted to mirror the order in which the pharmacist will either collect or interpret the data.

The benefits of a systematic approach are numerous. First, it allows the pharmacist to routinely organize information pertinent to the pharmaceutical care of the patient in a consistent manner. Second, systematic data collection allows the pharmacist to maintain a process during which potential drug-related problems may be evaluated. Third, this approach allows for ease of patient care “pass-off” should the pharmacist transfer care of a patient to another pharmacist. Additionally, the pharmacist’s collected data may become a resource for reporting on patient care during rounds, facilitating discussion with other healthcare practitioners, or documenting clinical interventions.

Initiating the Systematic Approach to Data Collection

A primary goal of systematically collecting data from the patient record should be to keep the process simple yet relevant and comprehensive enough for a pharmacist’s needs. A key in this process is not to overcollect data because it is available, but to be sure that there is a use and a reason for each type of data being collected. Because this may become a routine activity as a part of patient care, efficiency and consistency in collection of data become important. For example, a pharmacist may have many patients under his or her immediate care and may need to review data on each of these patients.

Timing of patient data collection usually follows a three-point approach: a preencounter assessment, a mid-encounter assessment, and a postencounter assessment. Regardless of the setting, the role of the pharmacist in the preencounter assessment is often to gather data relevant to the care of the patient for a given task (e.g., clinic visit, patient care rounds), and this is typically conducted prior to meeting with the patient or provider team. Data can then be updated or augmented during the mid-assessment encounter with the patient based on additional findings or the patient interview. Finally, monitoring and follow-up of new or changed data should occur, and the data collection form updated accordingly in the postencounter assessment.

Types of Systematic Data Collection Forms

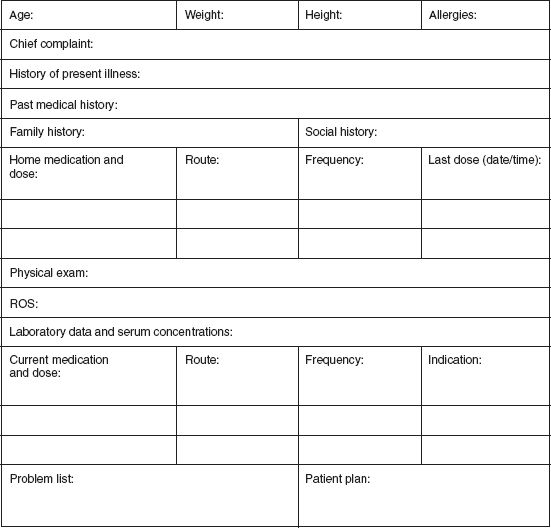

As discussed previously, data collection forms are often individualized to a given pharmacist or role in a clinical setting. An example of a data collection form is shown in Figure 2.4; however, this form serves only as a starting point to demonstrate that forms may be customized and include space for data. Individual forms will be tailored to meet the needs of the practitioner and will vary based on the practitioner or situation. Data on the form that is not within the scope of practice for the pharmacist to obtain may be collected from the medical record, as described previously. Data collection forms are heavily influenced by the manner in which the pharmacist is likely to assess the patient; therefore, the format and data vary based on the type of practice setting or provider service. Several factors may play a guiding role in the decision to use a particular type of data collection form, including the clinical setting (e.g., inpatient or outpatient), the role of the patient care team (e.g., primary team or consult service), or the specific task presented to the pharmacist (e.g., assessment of a focused problem or a generalized workup of the patient). Regardless of the nuances among data collection forms, applying a systematic method of data collection from a patient’s medical record is key to ensuring consistency in the approach, assessment, and plan for each patient.

FIGURE 2.4 Sample pharmacist data collection form.

PHARMACY-RELATED COMPONENTS OF THE PATIENT MEDICAL RECORD

A critical skill for the efficient pharmacist is to review the data with several key pharmacy-related aspects in mind; this will permit concise data collection while providing the pharmacist with adequate information to develop recommendations to optimize pharmacotherapy. Depending upon the patient care responsibilities of the individual pharmacist, the pertinent pharmacy-related components of a patient’s chart may vary. For example, an infectious diseases clinical pharmacist may dive right into the chart to seek out antibiotic orders and laboratory data for serum drug concentrations and renal function assessments, whereas a cardiology pharmacy specialist may initially search for blood pressure values from the physical examination in order to assess the effectiveness of a patient’s antihypertensive drug regimen. Regardless of specialty or focus, several general pharmacy-related components are contained within each portion of the medical record.

Medical History

The medical history (H&P) is a key area for identifying drug-related problems, which will be discussed at length in the final section of this chapter. Thus, the majority of information contained within the H&P is valuable in developing an assessment and plan for interventions to optimize pharmacotherapy. The pharmacist may find data lacking in some areas, which will require clarification via additional patient interviewing. For example, a patient’s chart may indicate an allergy to penicillin, but the specific reaction not be identified. The pharmacist can then question the patient to obtain and document this important piece of information. Similarly, components of the medication history may not be complete. For example, the H&P may note a medication list without doses or frequency of administration. The pharmacist can question the patient and even contact the patient’s pharmacy to obtain this information for documentation in the chart and on the pharmacist’s data collection form.

Additionally, physical findings may be germane to assessing the patient’s response to medications that are either missing or not documented in the chart. These require the pharmacist to perform the appropriate assessment technique to obtain and document the finding. For example, the physical examination of a patient who presents to the hospital with nausea and vomiting resulting from phenytoin toxicity should note the presence or absence of nystagmus, a finding associated with supratherapeutic serum concentrations of the drug. If this information is not found in the medical record, the pharmacist should perform the appropriate assessment (in this case, the H test to assess for nystagmus) and document the finding accordingly.

Throughout the H&P, the pharmacist can identify pertinent positive and negative components that are key to the development of an assessment and plan. This becomes especially important when gathering data from the HPI, ROS, and PE. The importance of pertinent positives can be easily rationalized, while pertinent negatives are not so obvious. For example, if the family history of a 39-year-old man presenting to the emergency department with a myocardial infarction indicates no family history of coronary artery disease, it is a pertinent negative fact to note on the data collection form, because it might be expected that someone in the patient’s family would have preexisting cardiac disease. Another example would be a patient presenting with pneumonia who has no shortness of breath (SOB). The pharmacist should document “no SOB” in the ROS of this patient, because it is a pertinent finding for this patient. A large majority of the H&P is relevant to the pharmacist’s data collection.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Test Results

In the lab section, pharmacists can focus on a number of pharmacy-related data points, including labs reflecting effects of disease states and medications on organ systems (e.g., serum creatinine, liver function tests, CBC, urinalysis), serum drug concentrations (e.g., vancomycin, phenytoin, digoxin), and cultures. Again, pertinent negative values are important to document, because some patients may have some unexpectedly normal labs (e.g., normal liver function tests in a patient with a history of liver disease). Diagnostic test results become important for the pharmacist to gather in order to understand the status of the patient’s various healthcare needs. Again, normal results of diagnostic tests can be just as valuable as abnormal results (e.g., normal electrocardiogram in a patient with chest pain) and thus should be recorded by the pharmacist on the data collection form.

Clinical and Treatment Notes

As discussed previously, these areas contain a large amount of information. Many pieces of data here can be considered key pharmacy-related components, including:

• Updates to problem lists, including new or changed diagnoses

• Daily updates regarding the patient’s ROS and PE, including daily vital signs, ins and outs, etc.

• Nursing notes, including updated vital signs, ins and outs, pain scores, reasons for refused or delayed medication administration, intravenous line site status, daily body weights, etc.

• Input from specialists regarding the status of various problems on the patient’s list

• Prescriber rationale for changing a medication regimen, dosage, and/or duration

• MAR/eMAR, including confirmation that scheduled medications were administered, timing of medications (e.g., vancomycin, and aminoglycosides), timing of as needed medication administration (e.g., analgesics, antipyretics, sliding scale insulin), or fingerstick blood glucose results

NAVIGATING CHOPPY WATERS: WHAT TO DO IF INFORMATION IS MISSING AND/OR MISPLACED

One of the greatest challenges in gathering information from a patient’s chart is actually locating all of the required data. It is critical to collect all pertinent information from the medical record in order to create a thorough and complete assessment, problem list, and plan for an individual patient. It can be frustrating to search the chart for a piece of information and not find it where it should likely be. Several issues can arise when navigating the choppy waters of the medical record.

Missing Details

Details are often missed during the documentation of the PMH. For example, a patient who is HIV positive should have the year of diagnosis and the most recent viral load and CD4 T-cell counts listed. The chart of a patient with diabetes, for example, should have the type of diabetes documented (i.e., type 1 or type 2) as well as any associated complications (e.g., diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy). If these clarifying details are missing, they can often be located in other areas of the chart, including H&Ps from previous admissions or visits, previous lab studies, and even from interviewing the patient.

Information in the Wrong Location on the Chart

Information may be located in the wrong section of the chart. This most commonly seems to occur with the review of systems and the physical exam. It is important to remember that the ROS is not the PE; inexperienced practitioners may inadvertently document a physical finding in the ROS section, or vice versa. For example, shortness of breath may be documented in the pulmonary part of the PE, when it should be located in the respiratory system part of the ROS, because it is a symptom subjectively perceived and reported by the patient. This occasionally occurs with FH and SH; inexperienced providers may place information regarding marital status in the FH section, for example. When navigating a patient’s chart, the reader must be aware of the potential for misclassification of data and ensure that the data are properly placed on the data collection sheet.

Conflicting Information

Conflicting information may become an issue when multiple practitioners perform H&Ps on the same patient. For example, the PE performed by the medical student may note that the patient’s breath sounds are clear to auscultation bilaterally, whereas the resident physician has documented rales and rhonchi in the left lower lobe of the lung. Clarification of conflicting information may require reviewing further information in the chart in addition to speaking with the team of practitioners taking care of the patient. Additionally, the pharmacist may interview the patient and perform a physical assessment of the patient to determine a resolution for the conflicting information.

Locating All of the Information

Occasionally, it may be difficult to obtain a patient’s inpatient paper chart because it is being used by another practitioner or because it is sent with the patient when he or she leaves the medical floor for diagnostic testing (e.g., x-ray) or procedures (e.g., surgery). When this occurs, information gathering can begin with using the electronic medical record system to gather laboratory and dictated information. Any information that cannot be obtained in this manner can then be followed up on when the paper chart becomes available. Additionally, there may be a high demand for computer terminals on nursing floors or in a cramped ambulatory care clinic setting. Again, patience is key; it may be best to start with a review of the paper medical chart first and then review the electronic medical information once a computer becomes available. Alternatively, finding a separate, secure location with additional terminals, including a different medical floor or a medical library, will permit review of electronic information in a timely manner. It may also be helpful to perform reviews of medical records at “off hours” on the patient care floor, such as very early or late times of the day or during resident physicians’ mandatory conferences, because the demand for charts and computers is often lower at these times. Once gathered on a data collection sheet, the pharmacist can synthesize all of the key pieces of information in the medical chart to develop a comprehensive healthcare needs list.

SYNTHESIZING PATIENT INFORMATION: DEVELOPING A PROBLEM LIST

Once a patient’s information is gathered from all of the necessary sources, the pharmacist can create a comprehensive list of pharmacy-related healthcare needs that encompasses a patient’s disease states, drug-related problems, and/or preventive measures. This problem list should be prioritized, with the most clinically significant issues listed first. For example, a male smoker presenting to the emergency department complaining of shortness of breath who is diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) should have pharmacy-related problems associated with “CAP” listed as the number one healthcare need on his list, while smoking cessation will be lower in priority on the list. Creation of this list can be challenging; however, with an organized systematic approach, it can be done efficiently and effectively.

Disease States

Often referred to as medical problems, the disease states a patient has should be included in the healthcare needs list. These are often derived from acute diagnoses, as in the case of a patient in the hospital setting, and from the PMH. Practitioners such as physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners are the primary caregivers who diagnose and document these disease states in the medical record. Examples of disease states include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, otitis media, and CAP.

Drug-Related Problems

Drug-related problems (DRPs) are events or issues surrounding drug therapy that actually or may potentially interfere with a patient’s ability to receive an optimal therapeutic outcome.6 DRPs are separate entities from a patient’s specific disease state. In practice, the pharmacist can help determine the presence of actual or potential DRPs. Any observed DRPs should be added to the patient’s healthcare needs list and ultimately serve as the foundation for the pharmacist’s assessment of the patient. Each DRP can be considered as an overall problem, but may be expanded as specific problems are considered. Several DRPs have been described:6–10

• Indication lacking a drug. Each diagnosis or indication should be reviewed to determine the presence or absence of appropriate drug therapy, including synergistic or prophylactic drug therapy. Indications that need drug therapy, yet are lacking in any or complete therapy, should be evaluated further. An example of this DRP includes a patient with a history of coronary artery disease and hyperlipidemia who does not have any medications prescribed for hyperlipidemia. This DRP may also be observed in a patient with generalized anxiety disorder who has not received an antianxiety medication (e.g., a selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor, benzodiazepine, etc.).

• Indication with incorrect drug. Each diagnosis or indication should be reviewed to determine if the therapy associated with it is effective or correct, not only with the drug itself, but also with the route of administration. Often, this DRP warrants reevaluation as a disease progresses, patient tolerance increases, or efficacy is not observed. An example of this type of DRP would be a patient treated with intravenous vancomycin for Clostridium difficile colitis. The route of administration for vancomycin for this indication should be oral, because the intravenous route is ineffective.

• Wrong dosage. This DRP incorporates a drug dose that may be too high or too low. Both instances can alter the efficacy and safety of a therapeutic agent and requires evaluation. Additionally, dose frequency and duration should be evaluated. For example, a patient who is HIV positive and who receives atazanavir 200 mg daily as a component of her antiretroviral drug regimen would have this DRP on her problem list, because this dose of atazanavir is too low.

• Inappropriately receiving drug. This DRP may alternately be described as the patient having problems with compliance or adherence to a particular medication or regimen. However, this DRP may also pertain to patient misunderstanding about how a specific drug should be taken or lack of availability of the agent, perhaps due to manufacturing availability issues or patient financial issues. An example of this DRP would be a patient who misses 2 weeks of his treatment regimen for hepatitis C infection due to not receiving it in the mail from his mail order pharmacy.

• Adverse reaction to a drug. Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) should be assessed. If an offending agent is found, it may be discontinued. For example, if a patient receiving ampicillin on the inpatient floor breaks out into a rash following treatment initiation, she may be experiencing an ADR and should be appropriately evaluated.

• Drug interaction. Drug therapy should be evaluated as a whole for each patient, and the presence of potential or actual interactions with drug therapy should be considered and evaluated. This is especially important to assess when a patient is on medications with a high propensity for drug interactions, as in the case of a patient receiving rifampin for treatment of tuberculosis.

• Drug lacking indication. All drugs should be directly connected to a particular indication. If an indication is not present or is no longer present for a specific drug, the patient may need to be weaned off the agent or discontinue it. For example, a patient receiving hydrochlorothiazide who does not have hypertension on his problem list and who denies having high blood pressure should have this DRP documented on his problem list.

DRPs can vary in nature and often arise from the disease states present on the patient’s problem list. It is easy to become overwhelmed when trying to identify all of the DRPs for an individual patient. Thus, following an organized, stepwise process is key to ensuring that all DRPs are identified and prioritized properly.9 This organized approach is summarized in Table 2.4. Step 4 in Table 2.4 permits the pharmacist to quickly recognize if a DRP exists with a particular medication. If the answer to any of the first four questions is “no” or if the answer to the last question is “yes,” further investigation to identify DRPs is necessary. Once all DRPs are identified, they can be prioritized and merged into the problem list with the patient’s disease states.10

For example, consider the following patient encounter. An otherwise healthy patient arrives at the clinic after completing a trial of lifestyle changes for his recent diagnosis of hypertension. At this current visit, the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated, and, along with the prescribing practitioner, the pharmacist agrees to help develop a medication plan for this patient. The pharmacist reviews all necessary data, including the patient’s medical history, allergies, and contraindications, current hypertension guidelines, and appropriate drug information, and suggests to the prescriber that she initiate an antihypertensive medication at an appropriate starting dose and frequency. The pharmacist documents the patient’s DRP as “indication lacking drug.” Note that this is different from the physician-diagnosed medical problem, which would be “hypertension.” At follow-up visits with this patient, the pharmacist will likely assess the patient for additional potential DRPs, including potential nonadherence, drug interactions, and the presence of adverse drug reactions. If any of these were observed at the follow-up visit, the pharmacist could work with the prescribing practitioner to prioritize existing DRPs and create a plan for each problem.

TABLE 2.4 Steps to Recognizing DRPs

1. Know what the DRPs are. It may be helpful to keep a list in front of you until you feel more comfortable with them.

2. Gather patient data from the H&P and notes. Use an organized data collection sheet for recording all information required, including a draft of the patient’s problem list.

3. Isolate each problem on the problem list and identify the medications being administered for each problem. Creating a table like that shown below may be helpful:

| Problem List (in descending order of priority) | Medications Patient Is Receiving for Each Problem (drug, dose, route of administration, frequency) |

A drug information resource may assist with this step.

4. Screen each medication on the patient’s list with the following questions:

• Is it the right drug for the indication?

• Is it the right dose?

• Is the drug working?

• Is the patient taking the drug appropriately?

• Is the drug causing ADRs or drug interactions?

If the answer to any of the first four questions is “no,” or if the answer to the last question is “yes,” further investigation to identify DRPs is necessary.

5. Once all the DRPs are identified, they can be integrated into the overall problem list prioritized in order of most clinically significant to least clinically significant.

Source: Kane MP, Briceland LL, Hamilton RA. Solving drug-related problems. US Pharm. 1995;20:55–74.