The Medical Interview: Introduction

The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.

Sir William Osler, circa 1900

The position of clinician is one of privilege. Patients entrust clinicians with the most intimate details of their lives, and society rewards them with prestige, job stability, and a decent standard of living. With this privilege comes responsibility. Patients expect support, understanding, explanation, relief from their symptoms and/or cure of their ailments, and society expects clinicians to act in the best interest of their patients, subordinating their own self-interest.1

Modern medicine was built on the foundations of the biological sciences to improve the diagnosis and treatment of human suffering. The resulting biomedical model focused narrowly on the pathophysiology of disease caused by anatomic, biochemical, and/or neurophysiologic deviations from the norm. Within this framework the clinician’s task was to focus on identifying, describing, and determining the cause of diseases and then preventing, managing, and/or curing them. This focus led to the discovery and management of many genetic, infectious, and other medical diseases. However, scholarship over the past three decades has underscored some critical limitations of the biomedical model. For example, the model did not address symptoms that are caused by factors other than disease or abnormalities in anatomical, biological, and/or neurophysiologic states. The model also largely ignored the social, psychological, and behavioral dimensions of illness.2,3 Indeed, some medical professionals believed that “mental illness is a myth,” and some argued that it was not appropriate for medical professionals to attend to psychosocial issues—a stance that perpetuated the suffering of many patients and the healthcare professionals whom they sought for help.4

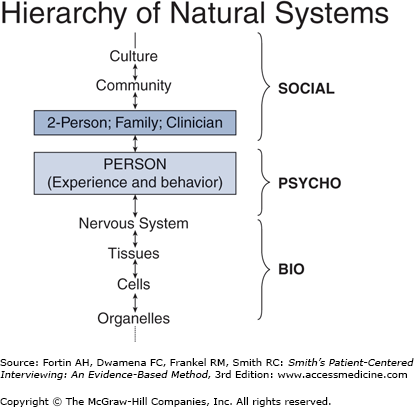

By the latter part of the twentieth century, it had become clear that the biomedical model was “no longer adequate for the scientific tasks and social responsibilities” of medicine.4 The human condition was noted to be too complex to be fully described and explained by the biomedical model alone. Engel proposed a biopsychosocial model to better explain how the symptoms and course of one patient with a particular disease can be completely different from those of another individual with the same disease.4,5 The biopsychosocial model explicitly acknowledges the interdependence of patients’ biological (disease), psychological, and social characteristics, making it consistent with general system theory (Fig. 1-1).

According to general system theory, disturbances in a system at one level have implications for other levels in the hierarchy of natural systems. A person is part of a hierarchy of systems that ranges from the smallest organelle to the largest community and culture and can be profoundly affected by changes in any of these systems. Unlike the biomedical model, the biopsychosocial model makes clear that the patient’s relationships (including the clinician–patient relationship) can be as important to the illness experience as the patient’s disease. It also explains why a person with no discernible pathology or significant aberration in physiology can experience debilitating symptoms and physical illness in the absence of disease.

Disease implies a disruption in normal biologic function. Disease is objective: you can see disease processes under a microscope and in abnormal laboratory or imaging tests. Illness is subjective: people feel a sense of “dis-ease”; they identify themselves as sick; they behave in accordance with the way they feel, which is different from how they act when they feel healthy. In many cases, they seek medical care. A patient can have disease without illness, as in an individual with hypertension who does not experience any symptoms; and illness without disease, as in an individual with hypochondria who is convinced that the slight and transient discomfort in her or his abdomen is due to cancer, not peristalsis.

Most patients who seek medical care have both disease and illness, in varying degrees. Some stoic patients can have serious disease but exhibit little illness behavior, while other more demonstrative patients may have little biologic disease yet be incapacitated. These are important distinctions relevant to daily clinical work, since patients come to clinicians with their illness experiences seeking relief of symptoms, and clinicians were traditionally taught to find and treat diseases. The distinctions between curing and healing now become clearer: we cure diseases with medications, surgery, and biotechnology; we heal illnesses mainly through our words and the therapeutic relationships we establish with our patients. To be most effective as clinicians we must be able to combine both curing and healing to benefit our patients.

Medical interviewing is the process of gathering and sharing information in the context of a trustworthy relationship that takes into account both disease, if present, and illness. Even in this age of medical advances, the medical interview remains the single most effective diagnostic tool, contributing to the correct diagnosis more often than physical examination or laboratory tests. Doctors and other healthcare professionals conduct over 100,000 interviews during their careers making the interview, by far, the most frequently performed medical procedure. Even a small improvement in your skills will have significant long-term benefits for you and your patients. The medical interview is what makes the clinician. Through your interviewing skill you will establish relationships with your patients that are meaningful, intimate, and caring. Your patients will tell you secrets they share with no one else. You will have a window on the world of human suffering and resilience and will develop respect for your patients’ courage and humanity. You will feel honored and privileged to be a healing presence in your patients’ lives.

This book describes an 11-step, evidence-based interviewing method used to obtain a complete biopsychosocial story that describes the person’s illness experience as well as her or his disease state and will guide you in ways to educate the patient and help change health-related behaviors. The patient’s story can include pertinent personal features of the patient, the effectiveness of the clinician–patient relationship, the family, the community, and the patient’s spirituality or lack thereof (Table 1-1).4,5

Step 1 Set the stage for the interview | |

1. | Welcome the patient |

2. | Use the patient’s name |

3. | Introduce self and identify specific role (student nurse/student doctor/resident/fellow) |

4. | Ensure patient readiness and privacy |

5. | Remove barriers to communication |

6. | Ensure comfort and put the patient at ease |

Step 2 Elicit chief concern and set agenda | |

7. | Indicate time available |

8. | Forecast what you would like to have happen during the interview |

9. | Obtain list of all issues patient wants to discuss; specific symptoms, requests, expectations, understanding |

10. | Summarize and finalize the agenda; negotiate specifics if too many agenda items |

Step 3 Begin the interview with nonfocusing skills that help the patient to express her/himself | |

11. | Start with open-ended request/question |

12. | Use nonfocusing open-ended skills |

13. | Obtain additional data from nonverbal sources: nonverbal cues, physical characteristics, accoutrements, environment, self |

Step 4 Use focusing skills to elicit three things: symptom story, personal context and emotional context | |

14. | Elicit symptom story

|

15. | Elicit personal context

|

16. | Elicit emotional context

|

17. | Respond to Feelings/Emotions

|

18. | Expand the story

|

Step 5 Transition to middle of the interview | |

19. | Brief summary |

20. | Check accuracy |

21. | Indicate that both content and style of inquiry will change if the patient is ready

|

Step 6 Obtain a chronological description of HPI/OAP | |

Step 7 Past medical history | |

Step 8 Social history | |

Step 9 Family history | |

Step 10 Review of systems | |

(Physical examination) | |

Step 11 End of the interview | |

The History of Patient-Centered Interviewing

Clinicians who were trained in the last century under the biomedical model were taught to interview patients using only clinician-centered

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree