The Middle of the Interview: Clinician-Centered Interviewing: Introduction

Give each patient enough of your time. Sit down; listen; ask thoughtful questions; examine carefully. … Be appropriately critical of what you read or hear. … Follow the example set by William Osler: ‘Do the kind thing and do it first.’

Paul Beeson, MD

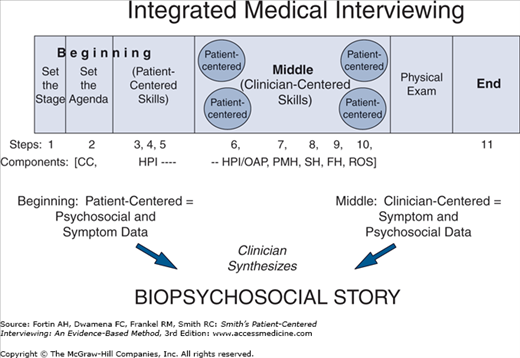

This chapter describes the steps involved in conducting the middle of the interview using clinician-centered interviewing skills. This part of the interview includes the latter part of the history of the present illness (HPI) and other active problems (OAP), continuing directly from the patient-centered HPI, and the past medical history (PMH), social history (SH), family history (FH), and review of systems (ROS).

Recall our progress to this point. During the beginning of the interview you used patient-centered interviewing skills to begin eliciting the HPI (Steps 1–5): you set the stage; obtained the chief concern and agenda; drew out the Symptom Story, Personal Context and Emotional Context; and made a transition to the middle of the interview, the point where we now find ourselves. There are five additional steps (Steps 6–10) in the middle of the interview, as shown in Figure 5-1. To illustrate each step, we will continue to follow Mrs. Jones.

Obtain a Chronological Description of the HPI/OAP—(Step 6)

Step 6 (Table 5-1) is the most important and most challenging part of the middle of the interview. The goal here is for you to develop and clarify the symptoms and secondary data that pertain to the patient’s symptom story. By the end of this step, you often will be able to make a disease diagnosis or, if not, you can greatly narrow the range of possible disease explanations for the symptom(s). This will guide what to most carefully look for during the physical examination and the subsequent laboratory evaluation, if any. The companion video available on the McGraw-Hill website (http://www.mhprofessional.com/patient-centered-interviewing) demonstrates what we will now describe. Module 8 in doc.com provides additional information about developing and clarifying the patient’s HPI.1

Step 6 – Obtain a Chronological Description of the HPI/OAP |

|

In almost all instances, you will have obtained a satisfactory overview of the HPI during Steps 2–4 but sometimes the patient’s description of the personal or emotional context of the symptom was urgent enough that you will not have gotten a good symptom description in Step 4. If this is the case, you can begin Step 6 by obtaining an overview of the major symptoms, when they began, and the most pressing current issue, using both open- and closed-ended skills. The problem usually, but not always, will concern physical symptoms.

Otherwise, as presented in Chapter 4, begin by converting each of the patient’s concerns to a standard symptom and further clarify it according to the seven descriptors (OPQQRST: onset and chronology, position and radiation, quality, quantification, related symptoms, setting, and transforming factors [aggravating/alleviating]). You will also need to know what other symptoms occurred before, during, or after the symptom under discussion.

As you talk with patients, you may begin to have ideas about what is causing the patient’s problems, and how the symptoms may be affecting physical functioning or activities of daily life. These ideas are known as “hypotheses” and the process of asking questions that make them more or less likely is called hypothesis testing. When you first learn how to interview patients, focus on first collecting as much data as you need to comprehensively describe the patient’s problem(s). Beginners often need to postpone hypothesis testing to a second interview after they have had time to read about the problems that have been described.2–4 As you become experienced and learn more about specific diseases and conditions, you will become faster, more efficient, and more accurate at gathering data and will learn to recognize patterns in the patient’s story that suggest certain diagnoses.5 Chest pain, for example, has well over 20 possible disease causes, such as, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, pericarditis, esophagitis, pneumonia, pleurisy, pulmonary embolus, costochondritis, and rib fracture. Each diagnosis has unique symptom and other diagnostic features and, often, different related symptom patterns. In the meantime, just ask the questions that will help you comprehensively describe the patient’s symptoms.

As a beginning interviewer, you can still test hypotheses during the interview but comprehensive questioning gives you data from which you can generate better and more hypotheses.2 Comprehensively question only in relevant areas, do not ask the same questions of every patient, and do not simply elicit all known symptoms from the entire ROS.2 As you acquire clinical experience and your knowledge base grows, hypothesis testing will become more prominent and comprehensive questioning will be less necessary. Nevertheless, even seasoned clinicians use comprehensive questioning in challenging cases when hypothesis testing is ineffective.2

Preclinical and beginning clinical students can generate a surprisingly relevant data base with the purely “descriptive” or comprehensive questioning approach. We will explore this in more depth next and then briefly consider how the more advanced clinical student integrates the hypothesis-testing approach.

Obtaining and Describing Data Without Interpreting It—for Preclinical and Beginning Clinical Students

For beginning students, Step 6 begins with two parts: A. Expand the description of symptoms already introduced by the patient and B. Inquire about symptoms not yet introduced that are located in the same body system.

Begin with the patient’s most important problem and identify all symptoms and secondary data starting from the onset of the concern. Group the concerns by common times of occurrence, translate each into a symptom, and then refine each symptom using the seven descriptors (see Chapter 4). At times, it is easier to first obtain the patient’s symptoms, and then fill in the secondary data (see Chapter 4). In either case, make use of repeated queries for temporal connections such as, “Then what?” or “What happened after that?” or “And then?” The patient sometimes will not introduce secondary data and so you must ask about prior treatment, procedures, diagnoses, and other secondary information. Alternatively, the patient may present a host of secondary data from which you must sift out the symptoms. For example, a patient might say, “This chest pain and shortness of breath occurred before my heart catheterization but after they found my cholesterol and blood sugar to be increased; that was when I was in the hospital last October for coughing up blood.” Here, the clinician must recognize the primary data (chest pain, shortness of breath, and hemoptysis) and not confuse them with the secondary data (heart catheterization, cholesterol, blood sugar, hospitalization).

Seek to understand the temporal (time) course of all data, using calendar dates and exact times when possible, and always for recent or acute problems. More remote problems often can be marked by weeks, months, or even years.

As you will see in the next vignette, the clinician uses closed-ended questions to elicit most information and offers periodic supportive remarks, maintaining a patient-centered atmosphere of warmth and understanding.

Clinician: | If it’s OK then, I’d like to shift gears and ask you some different types of questions about your headaches and colitis. I’ll be asking a lot more questions about specifics. |

Patient: | Sure, that’s what I came in for. |

Clinician: | I know the headache is the biggest problem now (chief concern). [The clinician will now elicit the seven descriptors of the symptom, recognizing that some were heard in Steps 3 and 4. If, however, the clinician somehow had not yet heard about the headache and other physical problems (because the patient expressed a pressing personal concern in the beginning of the interview), he would first obtain a detailed description in the patient’s own words.] |

Patient: | Yeah, it sure is. |

Clinician: | When exactly did it begin? [The interviewer wants to reaffirm the time frame of the headaches and uses a closed-ended question.] |

Patient: | Oh, just a few weeks after I got here. That’s about 4 months ago now, so the headaches have been about 3 months. [time of onset] |

Clinician: | How long does each headache last, the shortest and the longest they might last? |

Patient: | At least a couple hours. When they get bad, they’ll last up to 12 hours or so. [Further characterizing the onset and chronology by identifying the duration] |

Clinician: | What happens to the symptom during the time it’s there? |

Patient: | Well, it’s not so bad at first but it just keeps getting worse and then the nausea comes. [Time course of symptom] |

Clinician: | How many do you have in a week or a month? |

Patient: | I can have 2–3 a week when they’re bad. You know, every 2–3 days. [Symptom periodicity and frequency] |

Clinician: | How long have they been that often? |

Patient: | Since things got bad in the last month, especially the last couple of weeks. Before that they were only once or twice a week. [Total number can be calculated if important] |

Clinician: | You said the headache was in the right temple; can you point to it for me? [having gotten a good story of the onset and chronology, the interviewer shifts to understanding the position (location), referring to the patient’s description of the headache location in the beginning of the interview.] |

Patient: | (puts hand over much of right side of head) It’s all over here, sometimes larger than others. [Sounds more diffuse than specifically in one location] |

Clinician: | Is it always in the same spot? [The clinician is closed-endedly focusing away from the personal dimension and on the symptom itself, now getting the precise position] |

Patient: | Yes. |

Clinician: | Does it move any place else? [Another of what will be many closed-ended questions as the clinician continues to develop the seven descriptors of the symptom. Note that the clinician is introducing new topics and is also leading the conversation, appropriate for the middle of the interview.] |

Patient: | No, it stays right there. [No radiation] |

Clinician: | Does it feel like it’s inside your head or outside on the surface; you know, does it hurt to comb your hair or touch it? |

Patient: | No, it doesn’t hurt to touch it. It’s down inside I think. [A deep rather than superficial pain] |

Clinician: | Could you give me a description of what it feels like; such as aching, burning, or however you’d describe it. [It’s appropriate to give examples, if necessary, but provide more than one, with no particular emphasis, so as not to influence the patient.] |

Patient: | Oh, it’s more throbbing or pounding, like you feel each pulse beat. [Quality of the pain identified, and the patient offers no bizarre description] |

Clinician: | How do they begin, gradually or all of a sudden? |

Patient: | Oh, pretty much out of the blue. [Onset is sudden] |

Clinician: | Now I want to get an idea of how severe these headaches are. On a scale of one to ten, with one being no pain and ten being the worst pain you can imagine, like labor pains, what number would you give these headaches? |

Patient: | Well, they’re sometimes worse than having a baby! I’d give them a ten, especially when they get bad. And I’ve missed work a few days but not very often. [Quantifying the intensity and noting some disability] |

Clinician: | They sound pretty bad. You’ve really had a lot of trouble with this! [A respect statement. Empathic comments and behaviors are continued during the middle of the interview.] |

Patient: | You’re telling me! |

Clinician: | Do you know of anything that brings them on? [The clinician is not inquiring about the setting because she or he already knows that from the beginning of the interview] |

Patient: | Well, just what I’ve told you, getting upset. Once or twice it seemed like having some wine did it but I was stressed then too. [Perhaps another precipitant] |

Clinician: | Anything that worsens them once they’ve begun? |

Patient: | No, they’re bad enough already! Well, bright lights sure do, now that I think about it. [A transforming (aggravating) factor identified] |

Clinician: | They sure have been bad. What seems to help them once they occur? |

Patient: | Just lying down in a dark room, and an ice bag on my head. Well, the narcotic shot they gave me in the emergency room took it away too. [Another transforming (relieving) factor elicited. Also, secondary data, the narcotic and the emergency room visit, are introduced by the patient] |

Clinician: | What about the nausea? When did it start? [With a full description of the headache symptom, the clinician is moving now to better define a related symptom, staying with primary data for the moment. Notice that a nonpain symptom has fewer appropriate descriptors; for example, one usually does not try to identify location or radiation of nausea.] |

Patient: | I’ve had it for about 2 months now, just when the headaches are bad. |

Clinician: | Help me understand better what the nausea is like. [A focused open-ended request] |

Patient: | Like I’m sick to my stomach and could vomit if it got worse. [Quality of nausea] |

Clinician: | And how does it begin? [A closed-ended question, as many of the subsequent inquiries will be] |

Patient: | Oh, it just kind of gradually comes on after the pain has been there awhile. [Gradual Onset] |

Clinician: | How bad is it, how severe? |

Patient: | It’s minor compared to the pain. It’s never really been the problem the pain is. [Not very severe or disabling] |

Clinician: | How often does the nausea occur? |

Patient: | Just when the pain gets bad. I’ve probably had it each time with the headache in the last month; that’s when the pain has been worse. [Number of episodes identified] |

Clinician: | You said this began about a month after the pain, so that means the nausea has been there about 2 months? [Mrs. Jones has previously indicated the time of Onset] |

Patient: | Yeah, but it’s been worse in the last month. |

Clinician: | How long does the nausea last once it begins? |

Patient: | Oh, about a couple hours, when the headache finally goes away. [Duration of nausea and Transforming (relieving) factor] |

Clinician: | Anything else that relieves it? |

Patient: | Not that I know. I tried some antacid but it made me worse [Other Transforming (aggravating and relieving) factors explored. Secondary data also introduced (antacid)] |

Clinician: | And what’s the time between each episode? |

Patient: | Same as the headaches, you know, every of couple days. [Intervals identified. Chronology of symptom and setting also can be inferred from what Mrs. Jones has said already since the nausea is linked to headaches] |

Clinician: | Ever throw up with them? |

Patient: | Just once. That’s when I went to emergency [Related symptom] |

Clinician: | How much did you vomit? |

Patient: | Oh, just enough to soak a hankie. [The clinician has obtained pertinent descriptions of the nausea and now has discovered another symptom, vomiting, which would now be similarly explored. Complicated patients, unlike Mrs. Jones, can take considerable time in obtaining appropriate details of each symptom] |

Clinician/Patient: | [Not recounted here, the clinician and patient now develop details of the patient’s vomiting and cough. As you gain experience, you will recognize that the headache, nausea, and vomiting go together. This allows you to develop the symptoms simultaneously and avoid the repetition that is noted earlier.] |

Clinician: | It sounds like you went to emergency once when it was bad. What’s been the time course of the headaches and nausea; you know, better, worse, or about the same? |

Patient: | They are getting worse. They last longer and are more often in the last 2 weeks. [The overall course of the primary data is learned.] |

Clinician: | Have you seen anyone for them? [A good description of symptoms and their course to the present has been obtained, and the clinician is beginning to move away from symptoms to associated secondary data.] |

Patient: | Nobody, except the emergency room a week ago. I thought the aspirin would help. |

Clinician: | Have you taken anything else? |

Patient: | Nothing except that one shot; a narcotic of some sort I think. |

Clinician: | Did they do any tests on you in the emergency room? |

Patient: | Yeah, they did a blood count and a urine test. |

Clinician: | Any scans or any X-rays of your head? [Recent inquiry is aimed at understanding pertinent secondary data. Notice the repeated use of closed-ended questions to obtain a more precise description of the symptoms.] |

Patient: | No. |

B: Inquire About Symptoms Not Yet Introduced that Are Located in the Same Body System(s) (and General Health Symptoms)

Until this point, the interviewer has addressed symptoms (and related secondary data) volunteered by the patient but there often are other symptoms (“related symptoms” from Chapter 4) that have not been mentioned, which either by their presence or absence are pertinent to making a diagnosis; the absence of a symptom can be just as diagnostically important as its presence. The clinician thus needs to develop a more complete profile of the patient’s problem(s).

You can often assume that symptoms in the same system are related to the same underlying disease process. You know what the patient’s major concerns are and can therefore identify the body system likely involved if disease is present. At this point, from the ROS, ask the questions under the involved system heading; for example, a patient with urinary hesitancy and increased urinary frequency usually (but not always) has a disease in the urinary system and so you would use closed-ended questions to inquire about the symptoms under that heading in the ROS (dysuria, nocturia, urgency, hematuria, particulate matter in the urine, and so on until you comprehensively questioned about all possible symptoms under the urinary system heading of the ROS). At times, however, a symptom can suggest more than one system as a source of disease; for example, shoulder pain can indicate disease in the musculoskeletal system (rotator cuff injury), gastrointestinal system (cholecystitis) or the cardiopulmonary system (angina). In this case, you would inquire about all possible musculoskeletal, cardiopulmonary and gastrointestinal symptoms (joint swelling, hemoptysis, orthopnea, vomiting, diarrhea, and so on).

Questioning in this way often uncovers symptoms the patient may have forgotten or not thought important, and can at times provide crucial diagnostic information; for example, in the preceding patient with urinary concerns, discovering the periodic presence of particulate matter in the urine in association with bloody urine suggests renal calculi. Frequently, however, the patient will deny most symptoms on the list, this is also diagnostically important; for example, the absence of gross hematuria in this patient would weigh against renal calculi as well as some bladder or renal diseases.

Inquiring about symptoms of general health (see the review of systems) fills out the symptom profile. Ask about appetite, weight, general feeling of well being, pain, and fever in most patients, whatever system their symptoms reside in. Many diseases, especially more serious ones, exhibit one or more of these general symptoms. In our vignette, the clinician relies predominantly on closed-ended questions, and continues to intersperse supportive remarks.

Clinician: | Any other symptoms you might have had? [A focused, open-ended request, phrased as a question] |

Patient: | Well, nothing that I think of. |

Clinician: | Ever had problems with dizziness or lightheadedness? [Because the patient’s major symptom, headaches, is a neuropsychiatric system symptom, the clinician is beginning to closed endedly inquire about other possible neurological symptoms in the neuropsychiatric system as well as relevant neurological symptoms listed primarily in head, neck, eyes, ears, nose, throat.] |

Patient: | Not now. I used to get carsick as a kid and did a couple times then. |

Clinician: | Ever had a fainting spell? |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Stiff neck? |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Any problems with your vision? |

Patient: | No. I don’t even use glasses. |

Clinician: | Any double vision? |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Difficulty hearing? |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Ringing in your ears? |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Any change in your sense of taste or smell? |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Any face pain? |

Patient: | No. [The clinician would continue exploring all remaining symptoms in the above systems of the ROS: facial paralysis; difficulty swallowing or with speech; difficulty elevating the shoulders; muscle weakness or movement difficulty; extremity numbness, tingling, decreased sensation, or paralysis; the shakes or tremor; difficulty with balance or walking; and seizures.] |

Clinician: | Besides the nausea and vomiting once, have you had any other digestive problems? [A focused, open-ended question starts a new area of inquiry. The clinician will now obtain a complete profile of the patient’s other major symptom, nausea.] |

Patient: | There haven’t been any. |

Clinician: | [Even though the patient indicates none was present, the clinician would now use closed-ended questions to go through the symptoms in the Gastrointestinal System not already addressed: appetite, weight, heartburn, abdominal pain, vomiting blood (hematemesis), bloody or black stools, constipation or diarrhea, dark urine or jaundice, and rectal pain or excessive gas. The clinician then shifts to general symptoms.] |

Clinician: | You’ve told me a lot already about this, but how’ve you been feeling in general? [A focused open-ended question introduces a new area of inquiry, her general health. Information about appetite and weight will already have been obtained during the above inquiry about gastrointestinal symptoms] |

Patient: | Great, except all these things. |

Clinician: | You’ve sure been through a lot. Any problem with fevers? Chills? Night sweats? Change in appetite? [The clinician continues to make empathic comments and asks some closed-ended questions about general health.] |

Patient: | No. [Therefore, there is no problem with general health symptoms of fever, chills, appetite or weight. Not included here, the interviewer completes the general health questions from the Review of Systems.] |

With experience, you will base the extent of this review of systems upon clinical acumen, and it almost always can be considerably shortened; for example, an experienced clinician might be comfortable already with a diagnosis of migraine and inquire only about “Have you ever had a stroke? Head injury? Recent fevers?” For beginning students, however, systematically going through all the possibilities is the best way to learn them.

Interpreting Data While Obtaining It: Testing Hypotheses About the Possible Disease Meaning of Symptoms—for Clinical Students and Graduates

From the gathering/describing interview, you now have a complete profile and chronology of symptoms. But, you have not interpreted or grouped them in a way that points to specific diseases that could cause them. Just recounting symptoms usually does not identify a disease. Nor have you accounted for potentially significant symptoms in other systems. Inquiring about all symptoms outside the involved system is not feasible, would take too long, is intellectually unsound, and is boring.2

More advanced clinical students should therefore, after completing parts A and B of Step 6, add two additional parts: C—Ask about relevant symptoms outside the body system involved in the HPI, and D—Inquire about the presence or absence of relevant nonsymptom data (secondary data) not yet introduced by the patient, before concluding with the third part, understand the patient’s perspective.

Ask about symptoms outside the involved body system if they are pertinent to a diagnosis you are considering. For example, in a patient with advanced rheumatoid arthritis who is feeling fatigued, asking about gastrointestinal bleeding symptoms (“any black stools?”), while outside the musculoskeletal system, is still warranted if you suspect gastrointestinal bleeding due to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy is causing the fatigue. In patients with more than one problem, you will need to inquire in multiple systems during the HPI.

D: Inquire About the Presence or Absence of Relevant Nonsymptom Data (Secondary Data) Not Yet Introduced by the Patient

It is important to know about any medications taken to relieve the symptom, diagnoses given for the symptom in the past, prior treatments, and clinician visits or hospital stays for the symptom. This is especially true for complementary and alternative medicine treatments. Research shows that patients, as a rule, will not volunteer information about complementary and alternative treatments, therefore you must ask specifically and concretely about their use and do so in a nonjudgmental way.6 Also, asking relevant questions about possible etiological explanations for the diagnoses being entertained may help narrow the differential diagnosis. For example, if pulmonary embolism is a concern, ask about recent long car rides or air travel; if lung cancer is a hypothesis, ask about cigarette smoking.

How do you test hypotheses during the interview? Based on unique symptom(s) characteristics and secondary data suggesting one diagnosis over the others, and based on knowledge of what diseases are most common, you rank-order disease possibilities in your mind starting from the opening moments of the interview.2,5,7 Then, as noted earlier, seek additional diagnostic data (primary and secondary) to support the current best choice, almost always via extensive closed-ended questioning. If complete data have already been obtained descriptively, the new data will be largely outside the involved system. If not supported, another disease hypothesis becomes the best choice (“next best choice”) to explain the symptom(s) and you will similarly explore it. By following this process of testing multiple, ever-changing best hypotheses, you will eventually arrive at the best diagnostic possibility, the “current best hypothesis”—which is the best fit of our patient’s primary data (and secondary, if available) with a known disease.

It is not uncommon to start with one disease hypothesis (angina) and, based on symptom descriptors and associated symptoms, end with a quite different one (esophagitis). For example, because of substernal chest pain radiating into the arms, the student’s first hypothesis was angina. But, she or he knew esophagitis also was a possible cause of chest pain radiating to the arms and asked about descriptors and other symptoms associated with this diagnosis and they were present (precipitation of pain by coffee or recumbence, relief by belching and antacids, poor appetite) and other descriptors expected with angina were not present (no relationship of pain to exertion, no dyspnea or diaphoresis). When a hypothesis is well supported, it becomes a “diagnosis.” A diagnosis can often be made from the history alone (eg, angina) but sometimes additional data from the physical examination (eg, elevated jugular venous pressure for a diagnosis of congestive heart failure) or the laboratory (eg, low hemoglobin for a diagnosis of anemia) are needed before you can establish a diagnosis.2

The more knowledge and experience you gain the more facile and efficient you will become in formulating the diagnosis and knowing the proper questions to ask in real time rather than in a subsequent interview. Nevertheless, virtually all beginning clinical students will find themselves fully synthesizing the diagnosis only after the interview—when they have read about the problem, talked again with the patient to clarify issues they overlooked, and discussed the problem with faculty and more senior team members. Although this vast topic of clinical diagnostics8 is outside the scope of this text, and you will study this material extensively during your clinical years of training, the process of clinical problem solving is illustrated in Table 5-2. The table shows how a clinician tests hypotheses while obtaining the HPI.

Clinicians proceed, much as Sherlock Holmes,2 by first obtaining a few bits of presenting data (eg, nonradiating chest pain, fever, acute shortness of breath, and a swollen left leg in a 70-year-old man) with which to generate the current best hypothesis (eg, pulmonary embolus) and then ask specific questions (eg, whether the patient has had hemoptysis) that would further support or detract from this hypothesis.2,7,5 In this example, the clinician asks about hemoptysis, previously unmentioned by the patient, because her or his first hypothesis was pulmonary embolus and this symptom is pertinent to its diagnosis. Let us say that hemoptysis was not present but the clinician pursued the hypothesis further by inquiring if the leg swelling was recent or if there had been any long trips or immobility of the leg recently, common findings of some diagnostic value in pulmonary embolism. We’ll suppose that symptoms began following a 12-hour car ride just 3 days ago and the clinician became more confident of pulmonary embolus as a possible diagnosis. |

Even though the diagnosis may be likely, the interviewer tests alternative hypotheses—other diseases likely to be causing this patient’s chest pain. For example, the advanced student also would consider questions supporting myocardial infarction (substernal location of pain, crushing or squeezing pain, diaphoresis), pneumonia (productive cough, chills), rib fracture (injury), pericarditis (pain relieved by sitting up and leaning forward, and aggravated by lying supine), lung cancer (weight loss, cigarette or asbestos exposure), and a host of other possibilities as long as they reflected reasonable possible causes of the patient’s chest pain and other symptoms. Notice that none of these symptoms had been mentioned previously by the patient, that the clinician introduced them closed endedly, that if left to a simple comprehensive questioning/descriptive approach and subsequent routine inquiry many would have been completely dissociated from the HPI (a history of chest trauma is usually asked about in the PMH and cigarette use is asked about in the SH), and that some may never have arisen without such hypothesis-driven inquiry (relief of pain by sitting up is not a routine question). |

The clinician in this case would of course proceed to obtain a complete history and physical examination and appropriate laboratory and imaging data to clarify her or his hypotheses and, hopefully, establish a diagnosis. |

Clinician: | Ever had problems with swelling or pains in your joints? [The clinician has the hypothesis that vasculitis might be causing headache and knows that this diagnosis is sometimes associated with arthritis. She or he is thus using closed-ended questions to inquire about specific primary data outside the system involved to support this hypothesis.] |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Ever had any dancing or bright, shimmering lights in your vision for a few minutes before the headache starts? [The beginning clinical level clinician has learned that this symptom (scintillating scotomata) is of diagnostic value in migraine and is properly inquiring specifically about it as a way to build support for the hypothesis of migraine headaches.] |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Because these could be what we call vascular headaches, you know, like migraines, I want to ask you some specifics about that. Do you use birth control pills or other hormones? [The clinician is beginning to formulate diagnostic hypotheses about what has caused the headaches. She or he suspects migraine from the clinical story and her knowledge of headaches. Accordingly, it is appropriate to obtain additional supporting diagnostic data and, hence, the question about birth control pills, as these can cause migraine headaches in some women. In addition, because head injuries also can cause headaches, the clinician will ask about that as an alternative hypothesis. Indeed, any possible causes that have been entertained could be further addressed in this way; for example, if the clinician were suspicious of meningitis from the story, perhaps because of intermittent fever and stiff neck, additional questions to support or refute that hypothesis would be in order: any rashes, sick contacts or other exposure, and whatever else the clinician considered important in supporting a diagnosis of meningitis.] |

Patient: | Yeah, I’ve been on them for the last 6 years. [The clinician would pursue the type, doses, and experience with this later in the PMH.] |

Clinician: | Any family history of migraine? [Because this clinician knows that a positive family history supports the hypothesis of migraine, she or he includes these questions here rather than in the family history.] |

Patient: | One of my aunts had what they called sick headaches when she was young but they all cleared up when she got a lot older. |

Clinician: | By the way, have you ever had any head injuries? [The clinician is testing another non-migraine hypothesis for the headache.] |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Have you ever been unconscious for any reason? |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Any neck injuries or problems there? [Neck problems also can cause headaches and the clinician is exploring this hypothesis.] |

Patient: | Nope. |

By this point, you have elicited a detailed description of the patient’s symptom, performed a targeted ROS and, if you are a clinical student, sought symptoms in relevant body systems and obtained pertinent nonsymptom (secondary) data. Regardless of your clinical level, the patient’s history of present illness is not complete until you have a good understanding of the patient’s perspective on his or her illness. This is key to making an accurate diagnosis and being of the most help to the patient. Much of this information may have been elicited during Steps 3 and 4, particularly if you used indirect emotion-seeking skills in Step 4. The patient may also have related some of this data while answering your questions thus far in Step 6. Ask about each of the remaining areas now.

Ask, “How is this symptom affecting your life/work?,” “How has it impacted your family/spouse/coworkers?” [How an illness affects the patient and his or her family is important psychosocial information and it can have practical implications, eg, need for home services.]

Ask about the patient’s “explanatory model” of illness, “What do you believe is causing your (symptom)?” because it is critical to understanding how the symptom is affecting the patient and what is important to her or him;10 it can also give you an opportunity to correct misconceptions and address fears with an empathic response. It is useful to normalize this question by saying something like, “Many patients already have ideas about what’s causing their problems so I ask this question of everyone. It really helps me help them.” Occasionally, in eliciting a patient’s belief or attribution a patient will say, “You’re the clinician, you tell me!” Don’t get flustered by this response. Calmly explain, “I find that it helps to share each of our perspectives so that we can come up with the best treatment plan for you.” If the patient persists in saying that you’re the clinician and it’s your job, you can switch to a more clinician-centered interviewing style, having learned about a strong patient preference at the same time.

Another indirect emotion-seeking skill which, if not asked about in Step 4, should be elicited here is to understand the reason(s) why the patient came at this time: “What made you decide to see me today for this (symptom)?” This often provides a window on the patient’s personal life, important relationships and health beliefs (eg, a coworker with similar symptoms is recently told of a serious diagnosis, or a worried spouse insists that the patient seek care). Asking, “What else is going on in your life?” can uncover interpersonal crises or other sources of distress that can cause or amplify symptoms.11

In the case of Mrs. Jones, we learned in Step 3 and 4 that her headache is related to her work and a bit about the impact on her relationship with her husband. The student now asks several questions to learn more about her perspective:

Clinician: | You mentioned that troubles with your boss might be causing your headaches. How has all this affected you and your family’s lives? [Open-ended inquiry about the impact of the headaches on her and others’ lives. This question could have been asked in Step 4 (Chapter 3) as a way to “prime the pump” for personal context and as an indirect emotion-seeking skill if the patient had not spontaneously mentioned the personal context of her symptom story. Clinician-centered skills allow the clinician to take the lead like this to obtain necessary details about personal data.] |

Patient: | It’s been very disruptive. We were always quite happy and enjoyed things together. Even our love life has suffered. |

Clinician: | Say more about that. |

Patient: | For the past 3 months I just haven’t been in the mood much. We used to make love a few times a week, now it seems like once every few weeks, and now the kids seem to get on my nerves all the time too. Things need to get settled down. The job; not just the headaches. I’m not sure I’ll stay in this job if things don’t change. |

Clinician: | It’s been a difficult time. I do think we can help with the headaches, but I don’t know about your boss. [Interspersing a patient-centered intervention, here with naming and supporting statements, continues to be important. The student could pursue her sexual issues here, but there is also the opportunity to do so during the social history.] |

Patient: | He’s supposed to retire in 6 months. If the headache comes around, I can make it that long. |

Clinician: | I know you think the headaches are from your boss, but any other ideas about why you might be getting them? [The clinician is leading and shifting away from her boss and probing for any other beliefs about why she is ill.] |

Patient: | Well, I’m not really sure. At first I thought it was just because of my boss but they have lasted a long time now, are more frequent and are getting worse. |

Clinician: | Go on. |

Patient: | I know it sounds silly but the past couple of days I’ve been worried that I might have a brain tumor or something. |

Clinician: | I can appreciate why that thought would worry you. Thanks for sharing your concern. It really helps to know about it. We still have a lot of data to gather before coming to any conclusion but nothing you’ve told me so far makes me concerned about a brain tumor. I will keep your concern in mind and keep you as informed and up to date as possible. [The student offers respect and support.] |

Patient: | It’s a relief to know and it somehow feels less scary. |

Clinician: | Good. Any other thoughts about what might be causing the headaches? |

Patient: | Only punishment! I was raised with that always there. [Depending on the amount of time available, one could use patient-centered interviewing skills and explore this, allowing Mrs. Jones’ ideas to lead. On the other hand, it is not current and she is exhibiting no distress so that it also can comfortably be left until another time as the clinician does here. If it seemed relevant, the student could pursue any triggers for making the appointment now, but she or he seems to have gotten a good idea of her perspective on this illness.] |

Clinician: | That’s an important piece of information that I’ll want to come back to later or the next time I see you. Right now, I need to ask you some other questions about your colitis, cough, and your past health issues, if you feel finished talking about the headache. Anything else we need to cover, before we go on? [It continues to be important to note transitions, check if the patient is finished, and see if she or he has anything further to add to the topic at hand.] |

Patient: | That’s fine. You’ve covered everything, I think. [This evaluation by a beginning clinical level student shows how a novice interviewer first obtains data in the involved system to help develop hypotheses, then tests the hypotheses with selective questions designed to support or refute them, and wraps up with understanding her perspective. Not shown here because of space constraints, the interviewer now learns about the patient’s other active problems (OAP): her recent cough and her colitis. The write-up in Appendix D presents this information.] |

When the patient presents more than one concern, you will need to evaluate each one in much the same way. For example, Mrs. Jones also had colitis and a recent cough. These now could be systematically explored. If these are not currently active health problems, though, they can be explored instead as part of the PMH, in less depth. And when not contributing to current problems, as in Mrs. Jones’ situation, they are included in the PMH portion of the written report. When they are contributing to the patient’s current problems, they are included as OAP at the end of the HPI.

This is a lot to assimilate, and it will require much practice before you feel competent and confident interacting with patients. Review the demonstration video to get a better sense of the flow of the interview (see video at http://www.mhprofessional.com/patient-centered-interviewing). Once you learn the parts of the ROS and the symptom-defining skills in their clinical context, this process becomes quite reflexive. Typically, it does not take a seasoned clinician very long to obtain diagnostic and therapeutic information. With advancing skills and knowledge of diseases, you will learn which are the most pertinent questions and how to ask them efficiently rather than needing to ask all of them. In order to learn all the components of the interview, you will initially need to practice most of them in most encounters, which obviously will take time. (See the end of Chapter 7 for a discussion of how much time the interview will take for a beginning clinical student.)

Because you use predominantly closed-ended inquiry in the middle of the interview, two important issues must be raised: (1) Poorly conducted closed-ended inquiry can lead to considerable bias of the data. Table 5-3 lists important ways to avoid this. (2) Because you are in the middle of the interview and using clinician-centered skills, you can ask direct questions that insert new information into the conversation where necessary. This is especially helpful in testing hypotheses; for example, in a patient with a chronic cough, it is perfectly appropriate to introduce these thoughts: “Are you a cigarette smoker?,” “Have you lost weight?,” or “Have you ever been tested for TB?”

|