7

The Mathematics of Adverse Events and a Brief Note on Pharmacoepidemiology

This chapter is not intended to be a reference on statistics, epidemiology, or the technical mathematical aspects of data analysis. Rather, it is meant to give a very elementary and selective overview of some of the “numbers” used in pharmacovigilance and to show why, in our view, they have not been useful yet in clinical medicine and pharmacovigilance.

When a new adverse event (AE) begins to be reported in association with a new product, the two fundamental questions raised in the eyes of the regulator and the manufacturer are about rates (Will it?) and causality (Can it?).

Suppose that spontaneous reports of liver injury with drug X start coming in at the safety department or health authority. First, what is the likely causality link between the liver problem and that suspect drug? Were the patients exposed to only the suspect drug or were they simultaneously taking other products, including over-the-counters (OTCs), “natural” products, and so forth? Was the time to onset short enough to be very suggestive or was it so long that suspicion is rather low? Was there significant alcohol consumption? Was the patient in perfect health or was he or she at high risk of developing viral hepatitis? According to these and other diagnostic criteria, the clinician will roughly assess causality: definite, probable, possible, or unlikely. When enough details are available in a case report and when the report is complete enough, these judgments are feasible and they matter. We then say these reports are valid and (it is hoped) of high quality.

The next question is the rate of occurrence of this reported AE; in other words, what is the probability of the next patient exposed to product X developing severe liver disease? One in 10, 1 in 100, 1 in 1000? It is obviously important to know.

Over the years, many attempts have been made to apply statistics and epidemiologic methods to case series of AEs, primarily with spontaneously reported AEs. The results have been largely disheartening.

It is necessary to differentiate between AEs received in clinical or epidemiologic trials and those received spontaneously or in a solicited manner. The use of statistics is well described and defined for data generated in formal clinical trials. The patient populations to some degree are under the control of the investigator or researcher. The methodology for efficacy and safety analysis is well described and largely agreed on. Placebo- and comparator-controlled trials give clear pictures of occurrence rates of AEs, and significance values and confidence intervals can be determined and used to draw conclusions (at least for the efficacy criteria since the studies are usually not of sufficient statistical power to make safety judgments). The data are usually very solid, because data integrity is good to excellent. In addition, the data collected are usually complete. As patients are seen by the investigator at periodic intervals and as the investigator and his or her staff question the patient on AEs, it is believed that few AEs are missed, especially serious or dramatic ones. Incidence rates calculated from these data are held to be believable and useful.

Spontaneous reports are a different situation entirely. The data are unsolicited in most cases and may come from consumers or healthcare professionals. Follow-up is variable, and source documents (e.g., laboratory reports, office and hospital records, autopsy reports) are not always obtained because of privacy issues, busy physicians or pharmacists unable to supply records from multiple sources, patients’ not wanting to disclose information, and so on. If no healthcare professional was involved, such as when a patient uses an OTC product, the data usually cannot be verified. Hence, the data integrity is variable and inconsistent.

There are multiple biases involved in spontaneous data reporting that can produce cases that do not truly represent the situation. Two phenomena that act on spontaneously reported data are worth examining: (1) the Weber effect and (2) secular effects, described below.

Weber Effect

Weber Effect

The Weber effect, also called the product life cycle effect, describes the phenomenon of increased voluntary reporting after the initial launch of a new drug. “Voluntary reporting of adverse events for a new drug within an established drug class does not proceed at a uniform rate and may be much higher in the first year or two of the drug’s introduction” (Weber, Advances in Inflammation Research, Raven Press, New York, 1984, pages 1–7). This means that for the period of time after launch (from 6 months to as long as 2 years), there will be a large number of spontaneously reported AEs/adverse drug reactions (ADRs) that taper down to steady-state levels after this effect is over. It is to be distinguished from secular effects. This phenomenon has been seen in multiple other situations since the original report. (Replication of the Weber effect using postmarketing adverse event reports voluntarily submitted to the United States Food and Drug Administration. Hartnell NR, Wilson JP. 2004;24(6):743–749.)

Secular Effects

Secular Effects

Drug safety officers live in dread of reports of celebrities or politicians using a particular product, especially if an AE is reported or if spectacular efficacy or harm is anecdotally reported. This phenomenon is also called temporal bias and reflects an increase in AE reporting for a drug or class of drugs after increased media attention, use of a medication by a celebrity, a warning from a health agency, and so on. There are many multipliers of this effect over the internet, blogs, and other social media. “Overall adverse drug reaction reporting rates can be increased several times by external factors such as a change in a reporting system or an increased level of publicity attending a given drug or adverse reaction” (Sachs and Bortnichak, Am J Med 1986;81[suppl 5B]:49).

Reporting Rates Versus Incidence Rates

Reporting Rates Versus Incidence Rates

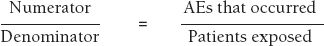

Perhaps the most difficult problem with spontaneous and stimulated reporting is incomplete data. Ideally, one would like to calculate incidence rates for a particular AE with a particular drug, where

However, the number of reports of an AE is always less than the true number of occurrences, because not all AEs are reported. It is estimated that in the United Kingdom only 10% of serious ADRs and 2–4% of nonserious ADRs that occur are reported (Rawlins, J R Coll Phys Lond 1995;29:41–49). In the United States, the FDA estimates that only 1% of serious suspected ADRs are reported (Scott, Rosenbaum, Waters, et al., R I Med J 1987;70:311–316). These figures are cited by the FDA in a continuing medical education article from the FDA entitled, “The Clinical Impact of Adverse Event Reporting” (October 1996) available on its website (Web Resource 7-1). In a study in Swedish hospitals, an underreporting rate of 86% for 10 selected diagnoses was found in one study (Underreporting of serious adverse drug reactions in Sweden. Bäckström, Mjörndal, Dahlqvist, Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety 2004;13(7):483–487).

The number of uncaptured AEs is therefore quite variable. This renders the numerator in the proportion quite suspect.

In addition, the denominator, patient exposure, is unknown. Although one can obtain prescription data and one can know how many tablets, capsules, or tubes were sold, it is hard to know how many people actually took the product in the manner and for the length of time prescribed. Should one count the patient who took one tablet once in the same way as someone who took three tablets a day for a month or a year?

Denominator data are reported in a number of ways including patients exposed, patient-time of exposure (number of patients times number of time units each patient took the drug such as patient-months or patient-years), tablets sold, kilograms sold, kilograms manufactured, prescriptions written or filled, and so on.

Nonetheless, by obtaining these data, crude estimates of reporting rates can be made. However, the numbers are often not terribly meaningful. The author recalls one widely used product for which 12 cardiac arrhythmia reports were received for what was calculated to be 9 billion (9,000,000,000) patient-years of exposure. This works out to 12/9,000,000,000 or a reporting rate of 0.0000000013 cardiac arrhythmia events/patient-years of exposure, which is not a meaningful number, particularly to a clinician who needs to make a decision on whether a particular patient should be given this drug. In fact, this number is so low that it is below the naturally occurring incidence of cardiac arrhythmias in the population, meaning marked underreporting of the AEs. Thus, one could argue that the drug in question actually prevents cardiac arrhythmias, which is clearly not the case.

The manufacturing data (kilograms manufactured) are available from the company producing the product, and the prescription information and the patient exposure data are obtained from various private companies that track such things (e.g., IMS Health Incorporated; see www.imshealth.com). Confounders include generic products in which the denominator is not included in the calculation but in which the company reporting on the branded drug receives and includes AEs (numerator cases) as well as counterfeit drugs where the denominator and numerator are compromised. Nonetheless, these data can be broken down by gender, age, and other demographic characteristics. Trends over time in usage can be observed.

In summary, as Dr. David Goldsmith has said, “the numerator is bad, the denominator is worse, and the ratio is meaningless.” Hence, one cannot calculate incidence rates for a particular AE based on spontaneous data, only reporting rates. Period.

However, the spontaneous data can be somewhat useful and new techniques looking at proportional reporting are under development. These include proportional reporting rate (PRR), gamma poisson shrinker (GPS), urn-model algorithm, reporting odds ratio (ROR), Bayesian confidence propagation neural network–information component (BCPNN-IC), and adjusted residual score (ARS). The PRR is described below.

Proportional Reporting Rate (PRR), Also Known As Disproportionality

There are various methods employed, and all more or less revolve around proportional reporting techniques. They look at the AEs for a particular drug and compare the same AEs for the remaining drugs in a database.

This basic PRR is simple and uses a 2 × 2 table:

| Drug of Interest | All Other Drugs | |

| AE of Interest | A | B |

| All other AEs | C | D |

PRR = [A/C]/[B/D]

For example:

| Drug X | All Other Drugs | |

| AE of Interest | 345 | 291 |

| All other AEs | 6901 | 14556 |

PRR = [234/6901]/[291/14556] = 2.5

In words, the proportion of a particular AE divided by all AEs seen with the drug of interest is divided by the proportion of this AE divided by all AEs seen with all the other drugs in the database (excluding the drug of interest). In the previous example, if 5% of all AEs seen with drug X are chest pain and 2% of all AEs seen with all the other drugs in the database (excluding drug X and its AEs), then the PRR is 5%/2% or 2.5. This means that there are (dis)proportionately more chest pain AEs with drug X compared with all the other drugs in the database, and this is noteworthy as a possible signal.

Since it is unusual that the PRR will be exactly 1.0, when the PRR is calculated for all AEs in the database, every PRR will either be below 1.0 or above 1.0. In theory, values below 1.0 would suggest a protective effect (the AE is less likely with drug X), and values above 1.0 would suggest an AE that is more likely due to drug X. Thus, one must be careful not to overinterpret the data, especially since there are more than 80,000 terms in MedDRA, and one could theoretically calculate some 80,000 PRRs. In practice, one sets a threshold above which the PRR is considered noteworthy, such as a value of 3.0. Any AE that has a PRR above 3.0 will be considered a signal and will be further examined. The higher the PRR, the greater the specificity but the lower the sensitivity. Alternatively, one might simply take the 10 or 20 highest PRRs and evaluate those regardless of how high the PRR is above 1.0.

There are other issues with using this score. When the database is small, problems can occur.

- For example, adding or subtracting one case can markedly alter the PRR results. For example, if there is one myocardial infarct (MI) in the four-patient database of drug X, this gives an incidence of 1/4 or 25%. Taking away the one case or adding one more MI would change the rate to 0% (0/3) or 40% (2/5). If the database had 1000/4000 cases, adding one or taking one away would have a negligible effect.

- Another problem may occur if the databases are inappropriate. It may not be appropriate to compare the incidence of a particular AE in the population treated with drug X against the incidence of that AE in the whole AE database. If the treatment for drug X is for, say, breast cancer, and is given only to elderly women, then comparing the incidence of an AE in the elderly female population versus the whole database in which elderly women are not predominant may give misleading results.

- Another problem may occur if drug X is frequently prescribed with drug Y and drug Y is known to produce a particular AE. Unless this is accounted for, it may appear in a simple PRR that drug X caused the AE when it probably was drug Y that did it.

- Similarly, certain common comorbid conditions or diseases may produce a high number of AEs that are due to the disease and not the drug.

- Finally, if the safety database used for the denominator of the PRR is small or has a high proportion of a particular type of patient or disease this may also produce flawed PRRs.

Various other statistical methods, or filters, may be added to this calculation to refine the technique to attempt to increase sensitivity. Some have adopted a rule of thumb that signals are worth pursuing if the PRR is more than 3.0, the chi-squared value is more than 4, and that there are at least three of the particular AE in question. Thus, if one has a sufficiently large database, the PRR could be programmed to run periodically (e.g., monthly or quarterly) using the filters as noted to generate possible signals. This method will be less useful if MedDRA coding is not crisp and correct. As always, the issue here is generating too many signals with too many false positives for the personnel available to review the signals. For a further discussion of this and other signaling matters, see Chapter 19.

Other Data Mining Methods

Other Data Mining Methods

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree