Chapter 10

The Impact of Multimorbidity on Quality and Safety of Health Care

Jose M. Valderas1,2,3,4, Ignacio Ricci-Cabello3, and Concepción Violán3,4

1Health Services and Policy Research Group, Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, UK

2LSE Health, London School of Economics and Political Science, UK

3Institut Universitari d’Investigació en Atenció Primària Jordi Gol (IDIAP Jordi Gol), Spain

4Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain

Overview

- Multimorbidity has the potential for resulting in poor quality of care and increased threats to patient safety. Multimorbidity has been associated with better quality of care as measured by the combination of condition-specific indicators but worse care when assessed from a patient-centred perspective

- No study has focused on the evaluation of patient safety in multimorbidity

- There is a need for conceptual clarity in future assessments and for the development of valid and reliable indicators of quality and safety in multimorbidity, including the recognition that quality of care for these patients requires more than delivering care that is consistent with the current disease-specific guidelines

- Clinicians should apply caution when delivering care for these patients in the absence of evidence for the benefits and harm of available management options

- Health systems should focus on enhancing primary care-centred coordination and continuity of care and designing incentives systems that reward appropriate care for these patients.

Introduction

The fact that a significant proportion of patients suffer from multimorbidity induces a tension between a healthcare model centred around the patient and health services that are organized around the diagnosis and management of individual health conditions. This tension has the potential for resulting in poor quality of care and threats to patient safety.

In this chapter, we review the key concepts for understanding the potentially detrimental effects of multimorbidity on quality and safety along with the opportunities for beneficial effects, the evidence for the impact of multimorbidity on quality and safety of care, how discrepancies between different studies can be reconciled and discuss the implications for providing care for multimorbid patients.

Key theoretical issues on the impact of multimorbidity on quality and safety of health care

Quality of care has been traditionally considered to be a characteristic of the process of healthcare delivery, as assessed in relation to standards. Ideally, there should be empirical evidence that care that adheres to such standards contributes to the delivery of efficient and effective health care. We will use the same approach for defining patient safety as a characteristic of the process of care delivery oriented towards the minimization of harm resulting from the interaction with the health system.

Multimorbidity might have potentially detrimental effects on quality and safety. People suffering from multiple health conditions are more likely to require an increased number of healthcare processes (Boyd et al., 2005), which will also trigger the involvement of an increased number of health professionals. This increased complexity in the delivery of care may threaten coordination, continuity and safety, thereby decreasing the likelihood of receiving care that meets high standards of quality and safety. Alternatively, it may be argued that the increased interaction with the health services might well result in increased opportunities for receiving effective care and also that the intrinsic high-risk profile of these patients might result in an increased patient safety awareness by the health professional involved.

There is no doubt that the quality and safety of patients with multimorbidity must take into account the evidence for the management of each individual condition. High quality and safe care for a patient with hypertension, osteoarthritis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease must be informed by best practice guidelines for each of high blood pressure, osteoarthritis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. But it is also important to stress here that it must also incorporate considerations about multimorbidity itself and its implications for management. We can hardly speak of safe high-quality care for this patient if the potentially antagonistic goals are not adequately addressed, interactions between the corresponding medications are not carefully examined (see Figure 10.1) and adequate coordination does not ensure smooth follow-up and monitoring of each of the conditions and the health status of the patient, including liaising with the corresponding specialists, while at the same time avoiding overexposing the patient to unnecessary health care and their potential or actual complications. And yet, as we will see, all these issues have been grossly overlooked, restricting evaluations in most cases to the specifics of care for each separate condition.

Figure 10.1 Little is known about safety of care in patients with multimorbidity, but iatrogenesis related to polypharmacy is an obvious area for concern.

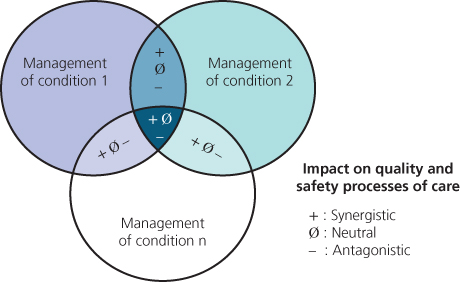

The management of concurrent health conditions may benefit from synergies when the conditions share a patho-physiological pathway. However, given any pair of conditions, their simultaneous management may be enhanced, impaired or simply not be affected, which can be termed as synergistic, antagonistic and neutral combinations (Valderas et al. 2009). This would separately apply to each specific management process (diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, etc.), and this may result in overall interactions between conditions that are not necessarily purely synergistic, antagonistic or neutral but rather mixed (see Figure 10.2). This is the reason why this approach to classifying interaction has been almost exclusively applied to a specific cluster of cardiovascular conditions, including coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and peripheral artery disease, where all the interactions are of the same nature.

Figure 10.2 Impact of multimorbidity on quality and safety.

Evidence for the impact of multimorbidity on the quality and safety of health care

Evidence on this issue is scarce. Just two studies have specifically studied the impact of multimorbidity on the quality of care, and no studies have focussed on the issue of patient safety in this highly vulnerable population, or at least it has not been addressed as a clearly distinct issue.

The most comprehensive study so far was conducted in the USA by Higashi et al. (2007) and included three large independent datasets. Researchers found that the overall quality of care, as measured using a database of several hundreds, mostly disease-specific indicators, increased with the number of comorbid conditions, and this relationship was maintained after controlling for the numbers of visits. In another study, multimorbidity was inversely associated with communication ratings. Ten groups of synergistic combinations of conditions were hypothesized, and the number of different groups in each patient showed a similar pattern of association with poor communication (Fung et al. 2008).

Although the picture that emerges is somewhat fuzzy because of the lack of a consistent approach and the somewhat contradictory results, it would appear that multimorbidity seems to be associated with worse quality of care when measured using a patient-centred approach. As for patient safety, the lack of evidence makes it impossible to draw any inference.

The main limitation of these studies is that they have failed to use indicators of quality of care (and patient safety) that are specific to the care of patients with multimorbidity. But the onus is not necessarily on these researchers. We simply lack well-validated and established indicators that are fit for this purpose. Out of the several hundreds of indicators used in the study by Higashi et al., none was specific for multimorbidity. The Quality and Outcomes Framework in the UK does not include at present any indicator specific for patients with multimorbidity, nor do the Quality Indicators used by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in the USA.

Implications for clinical practice

Clinical guidelines constitute the reference for the clinical management of patients, but, the applicability of current evidence-based guidelines to multimorbid patients is limited and can be problematic. This raises the fundamental question of whether not providing guidelines consistent care for people with multimorbidity represents poor quality care (an assumption made by all previous studies) or whether it actually reflects care that is sensitive to the particular needs of these patients (Box 10.1).

Box 10.1

Patients with multimorbidity have frequent contacts with multiple healthcare providers. Does this lead to better or worse care?

When is it appropriate for healthcare professionals to ignore the chronic disease treatment guidelines?

How can we define and measure improved outcomes in multimorbidity?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree