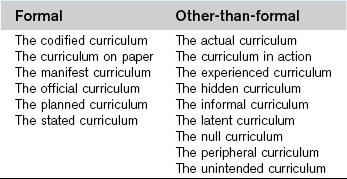

Chapter 7 Any attempt to penetrate and ultimately to exert an influence on the HC begins by dissecting the formal curriculum, and thus what is supposed to be going on, at least according to those in power. With this as our foundation, we then proceed to explore ‘what else might be happening.’ The space between the official and unofficial, the formal and the informal, the intended and the perceived, then becomes our primary workspace. In doing this work, it is important to remember that the HC is not a ‘thing’ that one finds, fixes and then puts aside. There always is a hidden counterpart to the formal and intended curriculum. Context always exerts an influence. There always are unseen, unrecognized and un- or underappreciated factors that influence social life, and there always are things that become so routine and taken for granted that they become invisible over time. Purposeful inquiry may uncover and intentionally address pieces of these influences, but no discovery is ever complete and no discovery is ever permanent. There is a constant cycling and recycling between the formal and other-than-formal aspects of social life. Furthermore, the HC system’s perspective requires us to acknowledge that any change in context and situation generates a new set of dynamics and thus new sets of influences which, in turn, help to construct new (overall) sets of relationships between the formal and hidden dimensions of social life. HC theory has deep conceptual roots within two academic disciplines: sociology and education. Philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey, for example, wrote on the importance of ‘collateral learning’ and the prevailing importance of indirect versus direct classroom instruction (Dewey 1938). For Dewey, the incidental learning that accompanies school and classroom life has an even more profound effect on learners than the formal or intended lesson plan. Dewey may not have used the term ‘hidden,’ but he clearly was concerned with the unintended, unnoticed and unconscious dimensions of learning. There also is a ‘hidden’ HC literature. There are many studies that draw upon the conceptual framework of HC theory without ever using key terms such as ‘hidden’ or ‘informal’. These articles will not be identified using keyword searches in databases such as PubMed or ISI Web of Science. One example is Campbell and colleagues’ examination of physician values regarding professionalism (largely quite positive and affirming) and the gulf that exists between these values and physician behaviours (Campbell et al 2007). The authors never reference the HC, but their article clearly highlights the difference that can exist between what physicians say and what they do and thus indirectly how students may be subjected to countervailing messages during their socialization into the physician’s role. In spite of a rather extensive literature on the HC, and in some cases because of this literature, there continues to be some confusion about what does, and does not, fall under the HC marquee. A few examples appear in Table 7.1, where they are roughly dichotomized into the formal (column one) and the other-than-formal (column two) dimensions of trainee and faculty learning. The formal curriculum is the stated and the intended curriculum. This is what the school or the teacher says is being taught. As you will note in Table 7.1, the formal curriculum has at least two dimensions. The first is that it is stated: be that in writing (course catalogue, website, course syllabus) or orally by a teacher. A second dimension is intentionality. What does the instructor intend to teach or convey to students?

The hidden curriculum

Relevance

Definitions and metaphors

Definitions