One clinical challenge posed by gastrointestinal (GI) tract symptoms is to distinguish the so-called “functional” (nonpathologic) from the “organic” (structural or pathologic) disorders, since some patients have hyperawareness of normal GI functions that may cause a variety of symptoms.

Psychological factors play a role in some of these functional symptom complexes.

Vomiting before breakfast is virtually always functional; diarrhea that does not disturb sleep at night is unlikely to represent a serious disease.

Vomiting before breakfast is virtually always functional; diarrhea that does not disturb sleep at night is unlikely to represent a serious disease.

In evaluating diarrhea the presence of urgency, tenesmus, and fecal incontinence suggest lesions involving the distal sigmoid colon and rectum.

In evaluating diarrhea the presence of urgency, tenesmus, and fecal incontinence suggest lesions involving the distal sigmoid colon and rectum.

Large volume diarrhea without the above symptoms suggests a small bowel site of involvement.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a “functional” disorder, has a characteristic symptom pattern that distinguishes it from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In IBS bleeding from the GI tract is absent and the cramping pain that occurs is usually related to defecation.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a “functional” disorder, has a characteristic symptom pattern that distinguishes it from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In IBS bleeding from the GI tract is absent and the cramping pain that occurs is usually related to defecation.

Diarrhea is the major symptom but intermittent bouts of constipation occur as well.

The characteristic pattern of the diarrhea in IBS is four or five bowel movements in the morning, ending by noon.

The characteristic pattern of the diarrhea in IBS is four or five bowel movements in the morning, ending by noon.

Bleeding or nocturnal diarrhea necessitates a work up for IBD.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

IBD, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC), have some similarities and many distinctions. UC is limited to the colon; Crohn’s involves the small bowel, the colon, or both.

Crohn’s disease is characterized by abdominal pain and, when the colon is involved, by GI bleeding.

Crohn’s disease is characterized by abdominal pain and, when the colon is involved, by GI bleeding.

Ineffable fatigue is a particularly debilitating feature of moderate to severe Crohn’s disease.

Ineffable fatigue is a particularly debilitating feature of moderate to severe Crohn’s disease.

Bleeding is invariable in UC because it is a mucosal disease.

Bleeding is invariable in UC because it is a mucosal disease.

The inflammation in UC progresses contiguously from the rectosigmoid; the inflammation in Crohn’s disease involves the ileum and the right colon with many “skip” areas.

The inflammation in UC progresses contiguously from the rectosigmoid; the inflammation in Crohn’s disease involves the ileum and the right colon with many “skip” areas.

The inflammatory process in Crohn’s disease is transmural, frequently with granuloma formation, and a tendency to form fistulas. Small bowel involvement in Crohn’s disease is a frequent cause of intestinal obstruction.

The inflammatory process in Crohn’s disease is transmural, frequently with granuloma formation, and a tendency to form fistulas. Small bowel involvement in Crohn’s disease is a frequent cause of intestinal obstruction.

Small bowel involvement in UC is limited to “backwash” ileitis.

UC is cured by colectomy; surgical resection in Crohn’s disease usually results in the re-emergence of Crohn’s disease in the unresected previously normal bowel.

UC is cured by colectomy; surgical resection in Crohn’s disease usually results in the re-emergence of Crohn’s disease in the unresected previously normal bowel.

Pancolitis in long-standing UC is associated with a high incidence of carcinoma, a fact favoring colectomy. The risk of colon cancer is increased in Crohn’s disease, but much less so.

Extraintestinal manifestations are common in IBD. These presumably have an immunologic basis, and include arthritis; erythema nodosum; episcleritis and uveitis; and with Crohn’s disease, mucosal erosions.

Extraintestinal manifestations are common in IBD. These presumably have an immunologic basis, and include arthritis; erythema nodosum; episcleritis and uveitis; and with Crohn’s disease, mucosal erosions.

The systemic manifestations in Crohn’s disease (fever, fatigue, anemia, and elevated indicia of inflammation) respond well to antagonists of tumor necrosis factor.

The systemic manifestations in Crohn’s disease (fever, fatigue, anemia, and elevated indicia of inflammation) respond well to antagonists of tumor necrosis factor.

Long-standing inflammation in patients with Crohn’s disease may result in secondary amyloidosis (AA).

Long-standing inflammation in patients with Crohn’s disease may result in secondary amyloidosis (AA).

Crohn’s disease is occasionally misdiagnosed as Behcet’s disease in patients who present with fever, arthritis, iritis or episcleritis, and mucosal ulcerations.

Crohn’s disease is occasionally misdiagnosed as Behcet’s disease in patients who present with fever, arthritis, iritis or episcleritis, and mucosal ulcerations.

The bowel symptoms in patients with Crohn’s disease may appear well after the above mentioned manifestations thereby causing confusion. In patients from the United States, not of Middle Eastern descent, Crohn’s disease, and not Behcet’s disease, is the usual diagnosis.

The arthritis associated with IBD (enteropathic arthritis) may involve the hips, knees, and the small joints of the hand.

The arthritis associated with IBD (enteropathic arthritis) may involve the hips, knees, and the small joints of the hand.

Deformities and bony erosions are very uncommon. An immunologic basis is presumed and activity of the joint disease frequently occurs with flares of the bowel disease.

Sacroiliac or spinal involvement (spondyloarthropathy) also occurs with IBD and is frequently associated with the HLA-B27 histocompatibility antigen.

Sacroiliac or spinal involvement (spondyloarthropathy) also occurs with IBD and is frequently associated with the HLA-B27 histocompatibility antigen.

The spondyloarthropathy may antedate the onset of bowel disease by several years.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding from Peptic Ulcer Disease

Upper GI bleeding (rostral to the ligament of Trietz) is much more common than bleeding from a lower GI site. Peptic ulcer remains the most common cause of UGI bleeding followed in frequency by esophageal or gastric varices secondary to portal hypertension.

Upper GI bleeding (rostral to the ligament of Trietz) is much more common than bleeding from a lower GI site. Peptic ulcer remains the most common cause of UGI bleeding followed in frequency by esophageal or gastric varices secondary to portal hypertension.

The identification of Helicobacter pylori as an important cause of peptic ulcer disease and the development of effective strategies for eradicating the organism, along with the development of potent proton pump inhibitors, has decreased the prevalence of peptic ulcer and its complications. Nonetheless, peptic ulcer is still the most important source of upper GI bleeding.

Epigastric pain that wakes the patient at night is particularly characteristic of peptic ulcer since gastric acid secretion is at its peak at about 2 AM.

Epigastric pain that wakes the patient at night is particularly characteristic of peptic ulcer since gastric acid secretion is at its peak at about 2 AM.

Peptic ulcer never causes pain on awakening in the morning since gastric acid secretion is at its low point at this time.

Peptic ulcer never causes pain on awakening in the morning since gastric acid secretion is at its low point at this time.

Many patients who present with upper GI bleeding from peptic ulcer will have no symptoms of prior peptic disease.

Many patients who present with upper GI bleeding from peptic ulcer will have no symptoms of prior peptic disease.

The physical signs of acute perforation of a peptic ulcer are striking. In addition to the classic “board-like rigidity” pain at the top of the right shoulder and resonance over the liver are characteristic.

The physical signs of acute perforation of a peptic ulcer are striking. In addition to the classic “board-like rigidity” pain at the top of the right shoulder and resonance over the liver are characteristic.

Shoulder pain reflects diaphragmatic irritation and is felt in the distribution of C 3, 4, 5. Hyperresonance over the normally dull liver is particularly striking.

Elevation of the BUN relative to the creatinine level is a very useful indication of an upper GI bleeding site.

Elevation of the BUN relative to the creatinine level is a very useful indication of an upper GI bleeding site.

Two factors favor BUN elevation with an upper GI bleed. 1) Diminished blood volume and blood pressure cause renal arterial vasoconstriction and thus decrease renal blood flow more than creatinine clearance. Decreased renal blood flow preferentially diminishes urea clearance because of back diffusion of urea in the distal nephron, a process sensitive to blood flow. 2) The protein load in the small bowel from the digestion of intraluminal blood results in increased urea production. Coupled with the renal hemodynamic changes, an increase in the gut protein load raises the BUN relative to the creatinine.

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (Osler–Weber–Rendu Disease)

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is a rare but significant cause of GI bleeding. Inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and consisting of telangiectasias (small arteriovenous anastomoses) located principally on mucosal surfaces, the disease usually manifests as GI bleeding in early adult life.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is a rare but significant cause of GI bleeding. Inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and consisting of telangiectasias (small arteriovenous anastomoses) located principally on mucosal surfaces, the disease usually manifests as GI bleeding in early adult life.

Telangiectasias on the lips are often visible but frequently overlooked, particularly in anemic patients or those who have just experienced GI bleeding.

Telangiectasias on the lips are often visible but frequently overlooked, particularly in anemic patients or those who have just experienced GI bleeding.

They manifest as small red macules that may have a square or rectangular shape and may be slightly raised. It is not uncommon for these to appear clinically after transfusions have been administered (just in time for the attending to make the diagnosis on the morning following admission). Bleeding may be chronic and low grade or brisk. Iron deficiency anemia is commonly present.

Epistaxis, particularly in childhood, reflects the location of these lesions on the nasal mucosa, and provides an important historical clue to the diagnosis in patients presenting in adulthood with GI bleeding.

Epistaxis, particularly in childhood, reflects the location of these lesions on the nasal mucosa, and provides an important historical clue to the diagnosis in patients presenting in adulthood with GI bleeding.

Lesions may also occur in the lungs and if sufficiently large may result in a right to left shunt. Rarely lesions in the CNS may cause subarachnoid or brain hemorrhage or brain abscess (strategically placed A-V anastomoses which broach the blood–brain barrier).

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding with a “negative” colonoscopy is either from angiomas (angiodysplasia) or diverticular vessels, since it is frequently difficult to identify bleeding that originates from these sites by endoscopy.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding with a “negative” colonoscopy is either from angiomas (angiodysplasia) or diverticular vessels, since it is frequently difficult to identify bleeding that originates from these sites by endoscopy.

Diverticular bleeding may be heavy but usually stops on its own.

Malabsorption

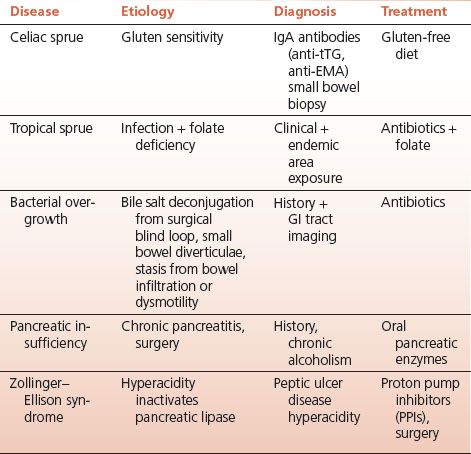

Malabsorption in adults may be caused by celiac sprue (nontropical sprue), bacterial overgrowth, tropical sprue, pancreatic enzyme deficiency, and certain infections (Table 11-1).

Steatorrhea, weight loss, diarrhea, and vitamin deficiencies are the major manifestations of malabsorption.

Steatorrhea, weight loss, diarrhea, and vitamin deficiencies are the major manifestations of malabsorption.

The diagnosis of malabsorption is confirmed by demonstrating fat in the stools, which are usually greasy, bulky, and foul smelling.

TABLE 11.1 Malabsorption

Vitamin deficiencies are characteristic manifestations of malabsorption: fat soluble vitamins are lost in fecal fat; mucosal abnormalities are the cause of folate and B12 malabsorption.

Vitamin deficiencies are characteristic manifestations of malabsorption: fat soluble vitamins are lost in fecal fat; mucosal abnormalities are the cause of folate and B12 malabsorption.

The associated clinical picture reflects the function of the deficient vitamin.

Severe vitamin D deficiency is associated with rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults. The alkaline phosphatase level (from osteoblasts) is always elevated and provides a useful guide to treatment with vitamin D.

Severe vitamin D deficiency is associated with rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults. The alkaline phosphatase level (from osteoblasts) is always elevated and provides a useful guide to treatment with vitamin D.

Normalization of the alkaline phosphatase reflects adequate treatment with vitamin D.

Celiac Disease

Celiac sprue (also known as celiac disease, gluten enteropathy, or nontropical sprue), caused by sensitivity to the wheat protein gluten, may be clinically manifest for the first time in adults of any age.

Celiac sprue (also known as celiac disease, gluten enteropathy, or nontropical sprue), caused by sensitivity to the wheat protein gluten, may be clinically manifest for the first time in adults of any age.

Although the manifestations of celiac disease may be subtle iron and folate deficiency are commonly present.

Although the manifestations of celiac disease may be subtle iron and folate deficiency are commonly present.

Iron and folate absorption are impaired in celiac disease since they are absorbed in the proximal small bowel, the region where the mucosal abnormality in sprue is the greatest.

Shorter than expected stature is a useful clue to the diagnosis of celiac disease in adulthood.

Shorter than expected stature is a useful clue to the diagnosis of celiac disease in adulthood.

Comparison of the height of the patient with that of the parents and siblings may serve as a reference point for short stature. Presumably, nutritional deficiency, even in the absence of characteristic symptoms of malabsorption, is the cause.

Celiac disease is diagnosed by serologic tests, small intestinal biopsy, and the response to a gluten-free diet.

Celiac disease is diagnosed by serologic tests, small intestinal biopsy, and the response to a gluten-free diet.

IgA antibodies directed at tissue transglutaminase (tTG-IgA) and endomysial antibodies (EMA-IgA) have high specificity and sensitivity for celiac sprue, the former being the currently preferred initial test.

IgA antibodies directed at tissue transglutaminase (tTG-IgA) and endomysial antibodies (EMA-IgA) have high specificity and sensitivity for celiac sprue, the former being the currently preferred initial test.

Small bowel biopsy is confirmatory showing a characteristic picture of flattened, atrophic villi and lymphocytic infiltration. The clinical manifestations and the histologic abnormalities are corrected on a gluten-free diet.

Intestinal lymphoma is an uncommon but troublesome complication of celiac sprue.

Intestinal lymphoma is an uncommon but troublesome complication of celiac sprue.

Celiac disease is associated with the unique (and rare) dermatologic disease known as dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) since it consists of crops of vesicles.

Celiac disease is associated with the unique (and rare) dermatologic disease known as dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) since it consists of crops of vesicles.

Most patients with DH have at least some evidence of celiac disease, but most patients with celiac disease do not have DH.

Many patients who do not have sprue report “sensitivity” to gluten.

Many patients who do not have sprue report “sensitivity” to gluten.

These patients feel better on gluten-free diets for reasons not understood. This “sensitivity” has been addressed by the food industry with a proliferation of gluten-free foods.

Tropical Sprue

Tropical sprue, in distinction to celiac disease (nontropical sprue), is a malabsorption syndrome endemic in tropical regions, and is probably caused by a combination of bacterial infection and vitamin deficiency, particularly that of folic acid.

Tropical sprue, in distinction to celiac disease (nontropical sprue), is a malabsorption syndrome endemic in tropical regions, and is probably caused by a combination of bacterial infection and vitamin deficiency, particularly that of folic acid.

Endemic in the tropics, particularly the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and southern India, nontropical sprue also affects visitors on prolonged stays in these regions. Onset is frequently with fever and diarrhea followed by chronic diarrhea and malabsorption.

Megaloblastic anemia is common in tropical sprue because of the folic acid deficiency and, occasionally, an associated B12 deficiency, the latter because folate deficiency affects the ileal mucosa and impairs B12 absorption.

Megaloblastic anemia is common in tropical sprue because of the folic acid deficiency and, occasionally, an associated B12 deficiency, the latter because folate deficiency affects the ileal mucosa and impairs B12 absorption.

Treatment entails a long course of antibiotics and folate.

Bacterial Overgrowth

Bacterial overgrowth in the small bowel may occur when motility is disturbed from autonomic neuropathy or an infiltrative process, when a blind loop is created surgically, in the presence of a large diverticulum in the duodenum or jejunum, or when a fistula connects the colon with the small intestine.

Bacterial overgrowth in the small bowel may occur when motility is disturbed from autonomic neuropathy or an infiltrative process, when a blind loop is created surgically, in the presence of a large diverticulum in the duodenum or jejunum, or when a fistula connects the colon with the small intestine.

Ordinarily, the small bowel contains only a fraction of the bacteria found in the colon; an increase in the small bowel population of bacteria affects the mucosa and alters the metabolism of bile salts.

Steatorrhea occurs with bacterial overgrowth because the bacteria deconjugate bile salts, thereby affecting the micelles that are essential for normal fat absorption.

Steatorrhea occurs with bacterial overgrowth because the bacteria deconjugate bile salts, thereby affecting the micelles that are essential for normal fat absorption.

Diarrhea complicates bacterial overgrowth since unconjugated bile acids irritate the colonic mucosa.

Diarrhea complicates bacterial overgrowth since unconjugated bile acids irritate the colonic mucosa.

B12 deficiency may occur with bacterial overgrowth since the bacteria compete with the host for cyanocobalamin; folate does not become deficient in overgrowth situations since the overgrown bacteria produce folate.

B12 deficiency may occur with bacterial overgrowth since the bacteria compete with the host for cyanocobalamin; folate does not become deficient in overgrowth situations since the overgrown bacteria produce folate.

Treatment entails surgical correction of the abnormality where possible; broad-spectrum antibiotics when the abnormality responsible for the overgrowth cannot be fixed as in diabetic neuropathy, scleroderma, or amyloid infiltration.

Pancreatic Insufficiency

Destruction of the pancreatic acinar tissue in chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, or inactivation of pancreatic lipase by hyperacidity in the presence of a gastrinoma, are the usual pancreatic causes of malabsorption.

Destruction of the pancreatic acinar tissue in chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, or inactivation of pancreatic lipase by hyperacidity in the presence of a gastrinoma, are the usual pancreatic causes of malabsorption.

Pancreatic enzymes supplied orally, and treatment of gastric hyperacidity, constitute treatment which is generally effective.

Infections and Malabsorption

Two infections may be associated with significant malabsorption: Whipple’s disease and giardiasis.

Two infections may be associated with significant malabsorption: Whipple’s disease and giardiasis.

Whipple’s disease, a widespread indolent infection with the gram-positive, PAS-positive, bacterium Tropheryma whipplei, infects the small intestine along with many other organs.

Whipple’s disease, a widespread indolent infection with the gram-positive, PAS-positive, bacterium Tropheryma whipplei, infects the small intestine along with many other organs.

Malabsorption occurs late in the course of the disease which has a predilection for middle-aged white men and is associated with arthritis as an early manifestation. Intestinal biopsy demonstrating scads of PAS-positive macrophages establishes the diagnosis.

Giardiasis, caused by the protozoal parasite Giardia lamblia, has a worldwide distribution and is spread by cysts that survive in cold water and by fecal–oral person-to-person transmission.

Giardiasis, caused by the protozoal parasite Giardia lamblia, has a worldwide distribution and is spread by cysts that survive in cold water and by fecal–oral person-to-person transmission.

Campers may be infected from cold water streams, and day care attendees from poor fecal hygiene. Water-borne epidemics also occur. The infection is not invasive but may cause an acute gastroenteritis; many cases are asymptomatic. In a minority of cases a prolonged chronic illness develops and in these cases malabsorption with weight loss may be prominent.

Zollinger–Ellison Syndrome (Gastrinoma)

Hyperacidity in the duodenum from gastric hypersecretion may inactivate pancreatic lipase giving rise to malabsorption.

Hyperacidity in the duodenum from gastric hypersecretion may inactivate pancreatic lipase giving rise to malabsorption.

THE PANCREAS

Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis has several causes: alcohol, gall stones, hypertriglyceridemia, many drugs, instrumentation of the biliary ducts, and congenital anatomic abnormalities of the pancreatic ducts.

Acute pancreatitis has several causes: alcohol, gall stones, hypertriglyceridemia, many drugs, instrumentation of the biliary ducts, and congenital anatomic abnormalities of the pancreatic ducts.

By far the most common causes are alcohol and gall stones. The common denominator of all the causes is autodigestion of the gland by the pancreatic enzymes which are released and activated by increased pressure in the obstructed pancreatic duct and by the cellular injury and duodenal inflammation induced by alcohol. The diagnosis is established by elevated plasma levels of amylase and lipase in the right clinical setting. The lipase level is more specific since amylase is produced by other tissues and amylase levels are elevated in other diseases as well as pancreatitis.

Epigastric pain radiating to the back with vomiting is the classic (and usual) presentation. Vomiting is almost invariable in all but the mildest of cases. Nothing by mouth is tolerated. Even sips of water cause reflex retching.

Epigastric pain radiating to the back with vomiting is the classic (and usual) presentation. Vomiting is almost invariable in all but the mildest of cases. Nothing by mouth is tolerated. Even sips of water cause reflex retching.

A common mistake in treating acute pancreatitis is feeding too quickly. Oral feeding stimulates pancreatic secretion which prolongs the inflammation. Once the pain subsides refeeding can begin.

It makes absolutely no sense to begin feeding patients with acute pancreatitis who still require narcotics for pain.

It makes absolutely no sense to begin feeding patients with acute pancreatitis who still require narcotics for pain.

In severe cases of pancreatitis extensive exudation in the abdomen occurs with local fat necrosis and the sequestration of large amounts of fluid.

In severe cases of pancreatitis extensive exudation in the abdomen occurs with local fat necrosis and the sequestration of large amounts of fluid.

The hematocrit may be very high (60%) due to hemoconcentration. Large amounts of fluid may be required early in the course of treatment to maintain the adequacy of the circulation.

Seepage of blood from the inflamed pancreas into the umbilicus or the flanks gives rise to Cullen’s and Grey–Turner’s signs respectively.

Seepage of blood from the inflamed pancreas into the umbilicus or the flanks gives rise to Cullen’s and Grey–Turner’s signs respectively.

Left-sided pleural effusion may also occur with pleuritis and atelectasis of the left lower lobe.

Left-sided pleural effusion may also occur with pleuritis and atelectasis of the left lower lobe.

Fat necrosis in acute pancreatitis may occur inside or outside the abdomen due to circulating pancreatic lipases; hydrolysis of triglycerides into free fatty acids then ensues, followed by saponification with calcium, resulting, in severe cases, in hypocalcemia.

Fat necrosis in acute pancreatitis may occur inside or outside the abdomen due to circulating pancreatic lipases; hydrolysis of triglycerides into free fatty acids then ensues, followed by saponification with calcium, resulting, in severe cases, in hypocalcemia.

The latter is a poor prognostic sign. It is no surprise that pancreatic inflammation may also impair insulin secretion giving rise to hyperglycemia.

Many years of heavy drinking usually precede the initial attack of pancreatitis. Recurrent bouts are the rule especially if the drinking continues.

Many years of heavy drinking usually precede the initial attack of pancreatitis. Recurrent bouts are the rule especially if the drinking continues.

In alcoholic pancreatitis damage to the pancreas is well established before the first acute attack occurs.

Stones in the biliary tract that obstruct the pancreatic duct are the other major cause of acute pancreatitis.

Stones in the biliary tract that obstruct the pancreatic duct are the other major cause of acute pancreatitis.

Passing a common duct stone may cause acute pancreatitis that varies in severity from mild to very severe. The amylase and lipase levels may be very high since the pancreas in these cases was normal prior to the passage of the stone. The enzyme elevations in this situation do not reflect the severity of the pancreatitis.

Hypertriglyceridemia is an uncommon but well recognized cause of acute pancreatitis. The triglyceride level is usually above 1,000 mg/dL in affected patients and the blood appears “milky” or lactescent.

Hypertriglyceridemia is an uncommon but well recognized cause of acute pancreatitis. The triglyceride level is usually above 1,000 mg/dL in affected patients and the blood appears “milky” or lactescent.

Lipemia retinalis is frequently noted on presentation in patients with triglyceride induced pancreatitis. Eruptive xanthomas may be present as well.

Lipemia retinalis is frequently noted on presentation in patients with triglyceride induced pancreatitis. Eruptive xanthomas may be present as well.

The blood in the vessels of the optic fundus looks like “cream of tomato” soup. Eruptive xanthomas are small yellow papules often with an erythematous base that may appear anywhere but are particularly common on the buttocks.

High triglyceride levels may obscure the diagnosis of pancreatitis by interfering with the amylase determination rendering it falsely low.

High triglyceride levels may obscure the diagnosis of pancreatitis by interfering with the amylase determination rendering it falsely low.

Lipase levels are probably not affected.

The elevated triglycerides usually reflect an impairment in lipoprotein lipase so that chylomicrons or chylomicrons plus very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) triglycerides are elevated (type I and type V in the Fredrickson classification of hyperlipidemias).

The elevated triglycerides usually reflect an impairment in lipoprotein lipase so that chylomicrons or chylomicrons plus very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) triglycerides are elevated (type I and type V in the Fredrickson classification of hyperlipidemias).

Frequently congenital, the defect in lipoprotein lipase may be induced by drugs such as alcohol or estrogen, or may occur de novo in pregnancy.

Hypertriglyceridemia is the most common cause of pancreatitis developing in pregnancy.

Hypertriglyceridemia is the most common cause of pancreatitis developing in pregnancy.

The high estrogen levels are the presumed cause.

Pancreatic divisum, a congenital anomaly in which the embryonic dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts fail to fuse, is an uncommon cause of acute and chronic pancreatitis.

Pancreatic divisum, a congenital anomaly in which the embryonic dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts fail to fuse, is an uncommon cause of acute and chronic pancreatitis.

Although most people with this anomaly are asymptomatic, in young patients without a history of alcoholism or gall stones the possibility of pancreatic divisum should be considered. Imaging the ducts establishes the diagnosis and sphincterotomy may be useful in treating recurrent attacks.

Drug-induced pancreatitis is a particular problem in HIV patients who take Bactrim for prophylaxis of pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) as well as antiviral agents.

Drug-induced pancreatitis is a particular problem in HIV patients who take Bactrim for prophylaxis of pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) as well as antiviral agents.

BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

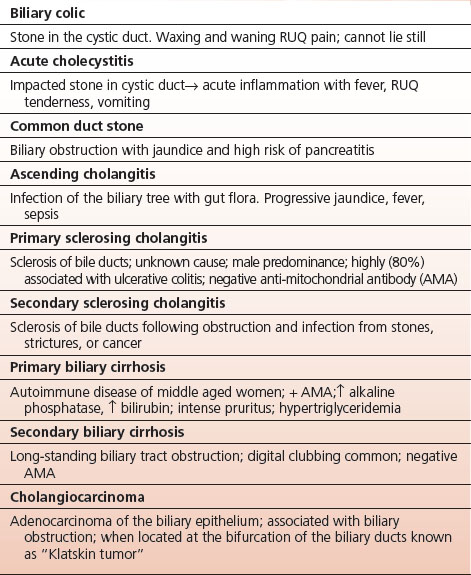

In addition to causing pancreatitis gall stones may cause biliary colic and acute cholecystitis (Table 11-2).

TABLE 11.2 Biliary Tract Diseases

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree