Chapter 9 THE EXOCRINE PANCREAS

Introduction

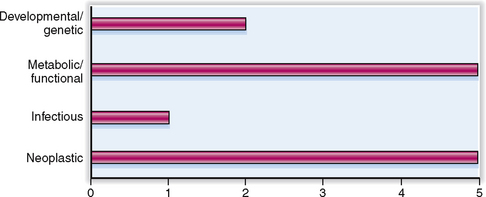

The relative clinical significance of various pancreatic diseases is presented in Figure 9-1. Diseases of the exocrine pancreas are not as common as other gastrointestinal diseases, but are nevertheless a significant clinical problem. Carcinoma of the pancreas is the sixth most common human cancer, and its incidence is increasing.

Normal and Structure and Function

ANATOMY AND HISTOLOGY

The pancreas is a solid retroperitoneal organ that has three main parts: head, body, and tail.

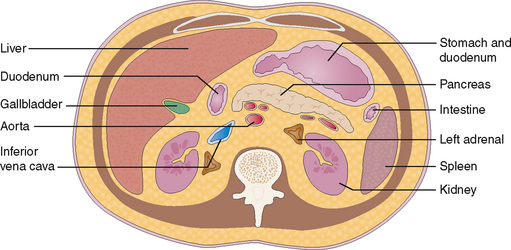

The normal pancreas measures approximately 15 cm and extends from the duodenum to the spleen. It is located in the retroperitoneum anterior to the aorta of the epigastrium and is fixed by fibrous tissue to the posterior abdominal wall. It is best visualized by computed tomography (CT, Fig. 9-2).

The exocrine pancreas drains into the duodenum.

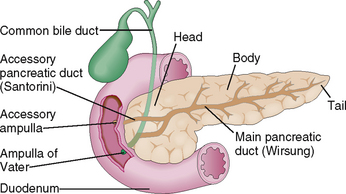

The pancreas is a mixed exocrine-endocrine gland that has three parts: head, body, and tail (Fig. 9-3). The digestive juices produced by the exocrine part of the pancreas drain into the duodenum through a system of ducts. Minor interlobular ducts originating from the intercalated ducts at the center of the acini fuse and ultimately form a major pancreatic duct (duct of Wirsung). Prior to entering into the duodenum, the duct of Wirsung fuses with the common bile duct forming an ampulla of Vater in 60% of cases. In the remaining 40% such a fusion does not occur, and many anatomic variants are present instead. Most people also have a separate accessory duct (the duct of Santorini), which branches from the main duct, entering the duodenum separately at its own ampulla. In many people such an ampulla does not exist, and the accessory duct ends blindly.

Anatomy and Physiology

Acinus Secretory unit of the exocrine pancreas. It is composed of several serous cells surrounding a lumen into which these cells secrete various digestive proenzymes.

Cholecystokinin Polypeptide stimulating the secretion of enzyme from the pancreatic acinar cells. It is produced, like secretin, by the endocrine cells of the duodenum.

Ductal cells Cuboidal cells lining the ducts of the pancreas. Serous cells secrete bicarbonates, whereas the mucous cells secrete mucus into the pancreatic juice.

Endopeptidases Group of pancreatic hydrolytic enzymes comprising trypsin, chymotrypsin, and elastase. These enzymes cleave polypeptides into smaller units (oligopeptides) composed of two to six amino acids. Approximately 70% of proteins in food are broken down by endopeptidases.

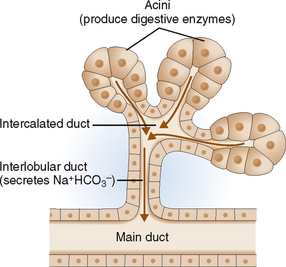

Intercalated duct Small duct that drains the acinar cell secretions into the larger pancreatic ducts.

Pancreas Major exocrine gland that also contains endocrine elements in the form of the islets of Langerhans. It is located retroperitoneally and extends from the duodenum to the spleen.

Pancreatic ducts The main pancreatic duct (duct of Wirsung) extends from the tail to the head of the pancreas. It joins the common bile duct prior to entering into the duodenum at the greater duodenal papilla (papilla of Vater). The accessory pancreatic duct (duct of Santorini) may be found in some people, bifurcating from the main duct and entering the duodenum at the lesser duodenal papilla.

Pancreatic enzymes Several digestive enzymes produced by the acinar cells of the pancreas. These enzymes act on lipids (lipase and phospholipase), proteins (trypsin, chymotrypsin, carboxypeptidase), carbohydrates (amylase), nucleic acids (deoxyribonuclease, ribonuclease), and elastic tissue (elastase), just to mention the most important ones.

Secretin Polypeptide hormone that stimulates pancreatic secretion of fluid rich in bicarbonate. It is produced by the endocrine cells in the duodenum.

Trypsin Pancreatic endopeptidase that cleaves proteins into oligopeptides composed of several amino acids. It is secreted by pancreatic acinar cells as trypsinogen, an inactive proenzyme that is activated in the intestine into trypsin through the action of enterokinases located in the intestinal brush border.

Zymogen granules Cytoplasmic granules containing proenzymes in acinar cells. These enzymes are excreted into the intercalated ducts and from there through the main pancreatic duct into the intestine.

Signs, Symptoms, and Laboratory Findings

Amylase test Normal serum levels of amylase are less than 140 IU/dL. Serum amylase is a sensitive marker of pancreatic diseases, especially if amylase is present in high concentration (>700 IU/dL). However, amylase is also produced by salivary glands and may be elevated in the serum in a number of other diseases, such as liver and intestinal diseases or renal failure. Amylase is excreted in the urine and may be detected in the urine in patients who have elevated serum amylase.

Cholecystokinin test Test used to detect chronic pancreatitis. Intravenous administration of cholecystokinin and secretin increases the volume of pancreatic secretion, which may be assessed by measuring the volume of juice in the duodenum and the concentration of bicarbonate and amylase. The test is technically difficult to perform. A peak bicarbonate concentration of less than 80 mEq/L is highly specific and suggestive of pancreatic insufficiency.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) Noninvasive radiologic technique based on the injection of contrast medium into the pancreatic and biliary ducts through a catheter introduced into the duodenal papilla of Vater. It is used to visualize the ductal abnormalities of the pancreas, including ductal fibrosis, obstruction, pancreatic stones, and tumors. The catheter introduced into the pancreatic duct may be used to obtain cytologic samples for microscopic diagnosis of cancer. Approximately 5% of all patients develop acute pancreatitis after this procedure.

Fecal fat content Test is based on collection of fecal material over 72 hours. Steatorrhea is defined as fecal fat content in excess of 7 g per 24 hours. The test is insensitive and becomes positive only if more than 90% of pancreatic acini are lost.

Lipase test Normal serum contains less than 130 IU/L lipase. Serum lipase is a sensitive marker of pancreatic disease. It is more sensitive and more specific for acute pancreatitis than amylase, especially after the first day of the onset of disease.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography Noninvasive radiologic technique used to visualize the pancreas and bile ducts, similar to ERCP.

Sweat test Test is based on measuring the concentration of sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) in sweat. The test is used to diagnose cystic fibrosis. On injection of pilocarpine the sweat of homozygous patients contains an increased concentration of Na+ and Cl− (>60 mEq/L). Sweat Cl− is a more sensitive test for cystic fibrosis than sweat Na+.

Trypsin test Normal serum contains 20 to 80 μg/L of trypsin. Serum trypsin elevation is a very sensitive test of pancreatic disease. It has, however, low specificity since trypsin may be elevated in serum in hepatobiliary, intestinal, and renal diseases. The serum trypsin is measured by a radioimmune assay, which makes it impractical for routine usage.

Pancreatic Diseases

Acute pancreatitis Acute inflammation of the pancreas related to intrapancreatic activation of pancreatic enzymes. It is characterized by autodigestion of the pancreas and adjacent tissues. The entry of activated pancreatic enzymes into the systemic circulation is typically associated with signs of shock.

Carcinoma of the pancreas Malignant tumor most often originating from the pancreatic ducts.

Chronic pancreatitis Chronic inflammation of the pancreas characterized by progressive fibrosis and calcification. Loss of pancreatic acini is accompanied by pancreatic insufficiency and malabsorption, whereas fibrosis usually causes persistent back pain.

Cystic fibrosis Autosomal recessive genetic disease related to the mutation of the gene encoding the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). The disease is characterized by abnormal secretion of pancreatic juices, as well as abnormal Cl− secretion in the mucus in the bronchi, hepatobiliary tract, and sweat. These patients are prone to infection and usually die in early adulthood due to repeated respiratory infections.

Histologically the exocrine pancreas consists of acini and ducts.

The secretory unit of the exocrine pancreas consists of acinar cells and excretory ducts (Fig. 9-4). The acinar cells are specialized protein-secreting cells arranged coronally around a centrally located intercalated duct. They are cuboidal and have abundant cytoplasm filled with zymogen granules. Zymogen granules contain proenzymes (zymogens) that are excreted into the ducts. The ductal cells are polarized and specialized for fluid and electron transport. These cells contribute bicarbonates, minerals, and water to the pancreatic juices. The ducts also contain scattered mucus-producing cells.

PHYSIOLOGY

Digestive enzymes are produced by the acinar cells.

Pancreatic acinar cells produce some 20 enzymes, which represent the primary digestive components of the pancreatic juice. These enzymes are proteins synthesized on the rough endoplasmic reticulum and packaged into membrane-bounded cytoplasmic granules. The contents of these granules are extruded into the intercalated ducts. Functionally these enzymes can be classified into several groups, most important of which are proteolytic, lipolytic, and amylolytic enzymes, and nucleases (Table 9-1).

| ENZYME CLASS | FUNCTION | TYPICAL ENZYMES |

| Proteolytic enzymes | Split peptide bonds of proteins forming oligopeptides and free amino acids | |

| Lipolytic enzymes | Hydrolyze the bonds between fatty acids and glycerol or cholesterol esters | |

| Amylolytic enzymes | Breakdown of starch | Amylase |

| Nucleases | Breakdown of DNA and RNA |

Nonenzymatic proteins secreted by acinar cells have regulatory functions but may also play a role in pancreatic diseases.

Trypsin inhibitor. It inactivates the prematurely activated trypsinogen. It is copackaged into granules together with trypsinogen, thus serving as an internal blocker of this proteolytic enzyme. Note that the activation of trypsinogen into trypsin occurs only in the small intestine under the influence of intestinal enterokinase.

Trypsin inhibitor. It inactivates the prematurely activated trypsinogen. It is copackaged into granules together with trypsinogen, thus serving as an internal blocker of this proteolytic enzyme. Note that the activation of trypsinogen into trypsin occurs only in the small intestine under the influence of intestinal enterokinase.

Protein GP2. It is linked to the inner surface of zymogen granules and is thought to prevent reflux of the extruded enzymes from the intercalated duct into the acinar cells.

Protein GP2. It is linked to the inner surface of zymogen granules and is thought to prevent reflux of the extruded enzymes from the intercalated duct into the acinar cells.

Lithostathine. The function of this protein is unknown, but it is thought that it may prevent the formation of pancreatic stones. However, both protein GP2 and lithostathine may form intraductal plugs in dehydrated persons and those with cystic fibrosis and chronic pancreatitis.

Lithostathine. The function of this protein is unknown, but it is thought that it may prevent the formation of pancreatic stones. However, both protein GP2 and lithostathine may form intraductal plugs in dehydrated persons and those with cystic fibrosis and chronic pancreatitis.

Pancreatitis-associated protein. This protein is found in low concentration under normal conditions, but it is present in high concentration in pancreatitis. It has been suggested that it has a bacteriostatic role, preventing infection and the formation of pancreatic abscesses.

Pancreatitis-associated protein. This protein is found in low concentration under normal conditions, but it is present in high concentration in pancreatitis. It has been suggested that it has a bacteriostatic role, preventing infection and the formation of pancreatic abscesses.

Pancreatic secretion is low during the fasting phase but increases 10-fold during the digestive phase.

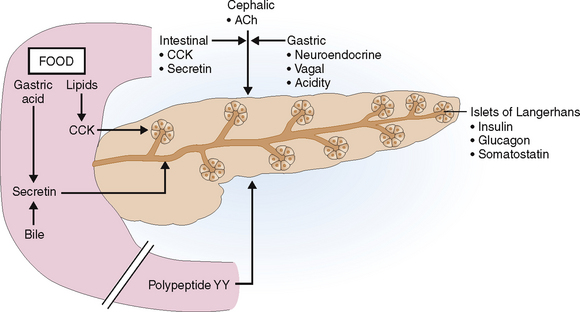

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is released from the duodenal neuroendocrine cells 10 to 30 minutes after ingestion of the food. The most potent stimulants for the release of CCK are lipids, but small peptones and amino acids in the food also stimulate these cells. The neuroendocrine cells of the duodenum that produce CCK-releasing factors may have a paracrine effect and also stimulate CCK release. Cholecystokinin stimulates the acinar cells to secrete pancreatic enzymes.

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is released from the duodenal neuroendocrine cells 10 to 30 minutes after ingestion of the food. The most potent stimulants for the release of CCK are lipids, but small peptones and amino acids in the food also stimulate these cells. The neuroendocrine cells of the duodenum that produce CCK-releasing factors may have a paracrine effect and also stimulate CCK release. Cholecystokinin stimulates the acinar cells to secrete pancreatic enzymes.

Secretin is released from the neuroendocrine cells in the small intestine mostly in response to intestinal acidification by the gastric contents admixed with the food. Bile acids and lipids also stimulate secretin release. Secretin stimulates release of bicarbonates in the pancreas. It appears that CCK and secretin act in concert because injection of pure secretin never has the same effect as a combined CCK-secretin stimulation or, for that matter, as food itself.

Secretin is released from the neuroendocrine cells in the small intestine mostly in response to intestinal acidification by the gastric contents admixed with the food. Bile acids and lipids also stimulate secretin release. Secretin stimulates release of bicarbonates in the pancreas. It appears that CCK and secretin act in concert because injection of pure secretin never has the same effect as a combined CCK-secretin stimulation or, for that matter, as food itself.

The digestive phase pancreatic secretion has three interval phases: cephalic, gastric, and intestinal.

Like other parts of the gastrointestinal tract the pancreatic digestive phase stimulated by food has three interval phases called cephalic, gastric, and intestinal (Fig. 9-5).

Cephalic phase. Mere exposure to food triggers the so-called cephalic phase, which is a reflex and most likely mediated by acetylcholine (ACh) released from the vagus nerve. It account for about 25% of the pancreatic secretion.

Cephalic phase. Mere exposure to food triggers the so-called cephalic phase, which is a reflex and most likely mediated by acetylcholine (ACh) released from the vagus nerve. It account for about 25% of the pancreatic secretion.

Gastric phase. Entry of food into the stomach starts the second phase. The pancreas is stimulated by polypeptide hormones released from the gastric neuroendocrine cells, vagal stimulation, and the changes in the pH in the contents that reach the duodenum. This phase accounts for 10% to 20% of the pancreatic secretion.

Gastric phase. Entry of food into the stomach starts the second phase. The pancreas is stimulated by polypeptide hormones released from the gastric neuroendocrine cells, vagal stimulation, and the changes in the pH in the contents that reach the duodenum. This phase accounts for 10% to 20% of the pancreatic secretion.

Intestinal phase. The third phase of stimulated pancreatic secretion begins with the entry of food into the duodenum. It provides 50% to 80% of the pancreatic secretion and is mediated mostly by CCK and secretin.

Intestinal phase. The third phase of stimulated pancreatic secretion begins with the entry of food into the duodenum. It provides 50% to 80% of the pancreatic secretion and is mediated mostly by CCK and secretin.

Clinical and Laboratory Evaluation of Pancreatic Diseases

FAMILY AND PERSONAL HISTORY

Family and person history may provide some clues about the nature of pancreatic diseases. Here we concentrate on acute pancreatitis as the prototype of pancreatic diseases. Later we will see that acute pancreatitis can progress to chronic pancreatitis. The risk factors for acute pancreatitis that may be discovered by careful history taken from the patient are listed in Table 9-2.

Table 9-2 Risk Factors for Acute Pancreatitis

| TYPE OF RISK FACTOR | SPECIFIC DISEASE/ASSOCIATION |

| Hereditary and metabolic diseases | |

| Social/nutritional factors | |

| Hepatobiliary diseases | |

| Infections | |

| Medical and surgical procedures | |

| Drugs | Thiazides, furosemide, valproic acid, azathioprine, corticosteroids, oral contraceptives, sulfonamides |

| External factors |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Shock, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and multiorgan failure

Shock, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and multiorgan failure

Weight loss with or without steatorrhea

Weight loss with or without steatorrhea

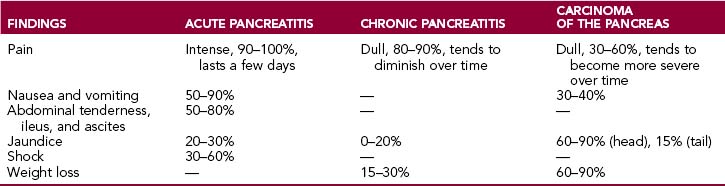

These symptoms may be present in both acute and chronic diseases of the pancreas, albeit in varying proportions (Table 9-3).

Epigastric pain is a feature of both acute and chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer.

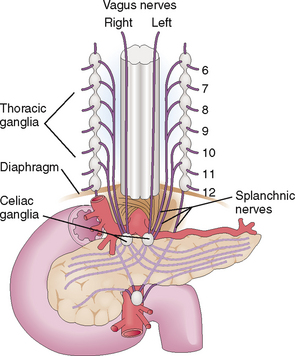

The pancreas has a rich innervation and contains numerous afferent nerve fibers that end in the celiac ganglia and the superior mesenteric ganglion (Fig. 9-6). Thus, many pancreatic diseases are accompanied by pain. However, the intensity, duration, and nature of the pain vary.

Acute pancreatitis is associated with pain in 80% to 90% of instances. It is intense, epigastric, and deep (“visceral”) and tends to radiate into the back. Often it is associated with “acute abdomen,” a term used if the patient is incapacitated by severe widespread abdominal pain, accompanied by nausea and vomiting, fever, and generalized tenderness to palpation. Such diffuse pain is a consequence of peritoneal irritation.

Acute pancreatitis is associated with pain in 80% to 90% of instances. It is intense, epigastric, and deep (“visceral”) and tends to radiate into the back. Often it is associated with “acute abdomen,” a term used if the patient is incapacitated by severe widespread abdominal pain, accompanied by nausea and vomiting, fever, and generalized tenderness to palpation. Such diffuse pain is a consequence of peritoneal irritation.

Chronic pancreatitis is accompanied by persistent nagging epigastric pain radiating into the back. Pain is often the most prominent symptom of disease, but its pattern, intensity, and frequency vary considerably. It may be mild or severe and intolerable. Sometimes it may be persistent, or it may last a few days, then stop for a day or two and then recur. The pain may be alleviated by bending forward and is aggravated by standing up. It may be worsened by intake of alcohol or food.

Chronic pancreatitis is accompanied by persistent nagging epigastric pain radiating into the back. Pain is often the most prominent symptom of disease, but its pattern, intensity, and frequency vary considerably. It may be mild or severe and intolerable. Sometimes it may be persistent, or it may last a few days, then stop for a day or two and then recur. The pain may be alleviated by bending forward and is aggravated by standing up. It may be worsened by intake of alcohol or food.

Pancreatic cancer is accompanied by pain in 60% to 80% of patients. It begins gradually and usually becomes more pronounced as the tumor spreads and invades the celiac plexus. Tumors of the tail and body are more likely to produce pain than tumors of the head of the pancreas.

Pancreatic cancer is accompanied by pain in 60% to 80% of patients. It begins gradually and usually becomes more pronounced as the tumor spreads and invades the celiac plexus. Tumors of the tail and body are more likely to produce pain than tumors of the head of the pancreas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree