Key stages in the development of the Physicianship Program. This timeline identifies key events during the sixteen-year period in which McGill’s Physicianship Program was developed. It demonstrates how the focus of the program evolved: from professionalism to physicianship, and, most recently, toward the incorporation of identity formation. It shows how the scope of the program expanded progressively (initially confined to the first-year class and eventually including all four years of the MD program), and how the teaching strategies became more complex. It also notes some of the important developments occurring in parallel to those taking place within the undergraduate medical program. It is important to point out that this schema does not include all relevant developments; for example, the introduction of the White Coat Ceremony (in 2001), the Physicianship Portfolio (in 2005), and modules in interprofessionalism (in 2006).

The Faculty adopted the term “physicianship” in order to represent the synthesis of healing with professionalism. The construct of physicianship, as understood at McGill University, refers to the roles of the medical practitioner: the physician as a healer and professional. The healer is considered the primary role whereas professional status is conceived of as the way in which the medical profession has organized its structures and activities to deliver healing services. It is assumed that the two roles are enacted simultaneously; they can, nonetheless, be understood, analyzed, and taught separately.

The Physicianship Program has been described in considerable detail in the academic literature. A philosophical pedigree has been proposed.16 The process of curricular renewal and the role of faculty development in institutional change have been explored.17 Patient perspectives on a curriculum grounded in the concepts of the physician as healer and professional were examined and their contributions to program development were reported.18 The educational blueprint, including its impact on the admissions process, has been outlined.19 Strategies relating specifically to teaching whole-person care and healing have also been elaborated.20 The teaching of the healer role, particularly in relation to reflective and mindful practice, is a focus of Chapter 7.

Physicianship also involved changes to certain specific educational practices, for example, in relation to the skills of the clinical method. It led to new approaches to teaching observation skills,21 attentive listening,22 and clinical thinking.23 The program also served as an incentive for the development of novel tools useful in the assessment of professional behaviors, both among students (with the Professionalism Mini-Evaluation Exercise – the PMEX)24 and teachers (with the Professionalism Assessment of Clinical Teachers – the PACT).25 In addition, the program delved into attitudinal domains, areas that in pedagogical terms are ill defined. Most notably, it promoted a set of personal attributes and underlined the importance for physicians-to-be to acquire self-knowledge. The specific set of attributes is captured in a Venn diagram; this representational figure is reproduced in Chapter 1 (Figure 1.3). The diagram identifies the personal characteristics unique to the healer and to the professional as well as those that are common to both roles. It also includes a description of the behavioral concomitants for the various attributes.

The flagship course for the Physicianship Program has been a longitudinal four-year course called Physician Apprenticeship. It, too, was first rolled out in 2005. Its goals are to (1) assist students in their transition from layperson to physician; (2) guide them in becoming reflective and patient-centered; and (3) provide a safe environment where they are encouraged to discuss issues arising out of their educational experiences. The apprenticeship provides opportunities for discussing the cognitive base of physicianship in addition to practicing the medical interview within clinically relevant settings. Although teachers in the apprenticeship are invited to teach certain clinical knowledge and skills, their raison d’être was, and continues to be, personal mentorship.

The Physician Apprenticeship (PA) groups, which are formed in the students’ first year, consist of six students, two senior medical students, and a clinical teacher. Given the size of McGill’s medical classes (approximately 180 students), this means that each cohort has twenty apprenticeship groups. With the exception of the student co-leaders, who graduate halfway through the program, they remain a stable group for the duration of the four-year curriculum. They meet as a group five or six times per year. There are also occasional one-on-one meetings between teacher and student.

The teachers in the apprenticeship are all clinicians. They are selected based on their reputation for good teaching (e.g., recipients of teaching awards, peer recommendations, and nominations from the student body). The students are randomly assigned to their PA groups by the Dean’s office. There is no attempt to match teacher and student according to age, sex, or ethnicity or to align students’ career aspirations with teachers’ specialties.

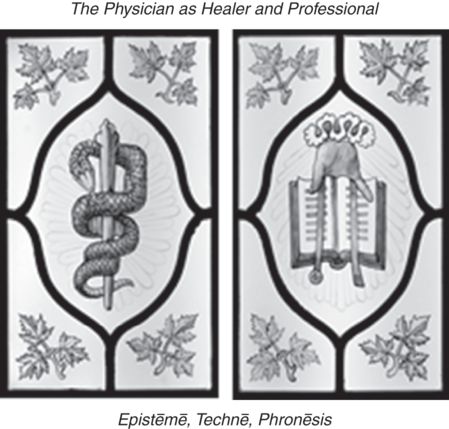

Based in the conviction that the teaching and learning of physicianship is inseparable from the transmission of values, the program emphasizes small-group discussions with prompts to stimulate personal reflections. It also aims to communicate its core values through symbols and rituals; this is illustrated in the following three design elements. First, the teachers in the Physician Apprenticeship are called Osler Fellows, named after Sir William Osler, important to the history of McGill, and a person who is universally recognized as the consummate and complete physician – a doctor to emulate. Second, to emphasize the healing mandate of medicine, the White Coat Ceremony is called Donning the Healer’s Habit. Third, the program adopted a logo to represent its conception of the philosophical fundaments and the ontogeny of medicine (Figure 15.2). The logo consists of two pictorial frames: one represents the healing function and the other represents scholarship. The catchphrase at the bottom of the logo’s pictorial frame is Epistēmē, Technē, Phronēsis. Those Greek words represent three different categories of intellectual thought, as per Aristotelian philosophy.

The logo of the Physicianship Program at McGill University. The frame on the left, the rod and serpent, originates from Greek mythology and is linked to Asklepios, the god of healing. The frame on the right, the “Heavenly Hand and Book,” dates to medieval times and is the traditional symbol of universities; the book represents learning and scholarship, while the hand symbolizes transcendent sources of wisdom. The maple leaves are a reminder to the fact that McGill University is a modern Canadian institution. The three Greek words at the base of the frames represent the aspirations of the Physicianship Program – that its practitioner will acquire universal knowledge from nomothetic sciences, become skillful in clinical methods, and aspire to practical medical wisdom.

Episteme is scientific reasoning; it emphasizes demonstration in logic and conclusions of a theoretical or abstract nature. In contrast, techne and phronesis both describe practical reasoning. The precise difference between these two modes of thinking is often debated. Suffice it to point out that the former is generally translated as craftsmanship and the latter as practical wisdom or prudent decision-making. Techne describes a process, the quintessence of which is in making or producing, during which there is the recognition of relevant generalizations (such as protocols or methods previously agreed upon by a community of practice). It culminates in an end or outcome that is external to the agent. For example, in the case of the navigator, the outcome might be a safe journey. Phronesis is a process with deliberation as its vital core. Combined with a disposition to act in a particular manner, deliberation culminates in a correct (good and right) course of action. In doing so, it contributes iteratively and inductively to the continued moral and intellectual development of the person; in contrast to techne, the end is internal to the agent. Techne can be taught and learned explicitly and is finely honed through experience; phronesis is acquired solely through experience and guided reflection.

The physicianship logo suggests that medicine is a fusion of theory and practice, with practice predominating. The incorporation of phronesis in the curricular blueprint acknowledges that medical education must attend to the development of identity. It also signifies the aspiration of the program, i.e., that its graduates will embark on the life-long process of acquiring clinical judgment and medical wisdom.

Specific elements of the Physicianship Program

So far, a general outline of the Physicianship Program has been provided. The reader, especially if engaged in an “on-the-ground” delivery of similar courses, may wish to be acquainted with more specific details. That is the purpose of this section.

We have found it critically important to meet with the students from the very beginning of medical school. Actually, physicianship is introduced on day one; students are offered a plenary session in which we outline the historical roots of the healing traditions and the professions. We define “healing,” “profession,” and “professionalism.” More recently, we have added the concepts of “identity,” “professional identity,” and “socialization” to that orientation session. Following the plenary, students are invited to a small group (sixteen students to a group) in which they have an opportunity to reflect on their personal motivations for medical practice and on their nascent professional identities (or “proto-professionalism”).26 Student feedback regarding these orientation sessions has been overwhelmingly positive; it helps them to set expectations – to calibrate their hopes and desires with the profession’s expectations. It is a motivational experience and it is reassuring for them to have the faculty speak of issues such as healing. This is followed a few months later by a session in which the focus is on the personal attributes of the healer and professional; the Venn diagram (Figure 1.3) serves as the organizing framework. The Venn diagram has become a sort of leitmotif for the program. Students are provided with vignettes that illustrate specific professional behaviors-in-action; they are asked to refer to the Venn diagram in analyzing the events and in suggesting corrective measures or appropriate responses. Over the years of conducting this session, we have found three aspects that are important for educational leaders to consider:

It is most effective to refer to contexts that are germane to students’ actual experiences; for example, it is better to discuss a hypothetical case of cheating in the classroom than an instance of disrespectful interpersonal interactions by team members during a hemodialysis treatment.

There is a tendency to focus on examples of unprofessional behaviors; it is wise to balance this with cases of exemplary behaviors (such as an illustration of a student initiative with the local indigenous population).

It is prudent to avoid stereotyping, such as, for example, overplaying the narrative of the arrogant surgeon in the operating room.

Recently, we have introduced a new module, with lecture and small group, on identity formation and socialization. Two sets of discussion prompts that we have found particularly useful are those that deal with “a first experience” (e.g., first time being with a dying patient; first time dissecting a cadaver) and those that invite reflections on perceived changes in one’s persona (e.g., an incident when one felt like a doctor or when one was treated as if they were a doctor). This session remains a work in progress.

In the second-year class, we introduce the social contract and discuss, again in small groups, reciprocal obligations and expectations of society and the medical profession. There are also interactive sessions on health advocacy. It is also at this juncture that the students gather to craft their class pledge. Each class creates its own pledge (an example of which can be found in Chapter 2). They read it aloud in front of their peers, faculty, family members, and loved ones at the White Coat Ceremony. This represents a public acknowledgement of a personal acceptance of professional values. Later on, the ceremony and its impact on personal meanings are explored in the context of meetings of the Physician Apprenticeship groups.

For the third-year class, the focus is on communication in teams. There is a preliminary whole-class interactive meeting followed by a conflict negotiation scenario, organized at the Simulation Center. Each student interacts with a standardized physician, resident, or nurse; the students are challenged to recognize personal and contextual factors that initiate and perpetuate conflictual situations. There are also panel discussions, with student, physician, and patient, where the healing function is discussed.

In their final year, the students revisit the social contract with a focus on self-regulation. The small groups use a variety of strategies such as debates and role-plays. In a separate meeting, they are prompted to consider how they will deal with the tensions inherent in the profession: altruism versus self-interest; respect for duty-hour regulation versus service; meeting professional obligations versus maintaining a healthy personal life; professional autonomy versus accountability. Students are also invited to consider how they will reunite the professional and healer functions of the physician.

The longitudinal Physician Apprenticeship has its own set of educational activities. These are summarized in Table 15.1.

| Year | Number of group meetings | Discussion topics | Learning activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 |

| |

| 2 | 6 |

|

|

| 3 | 5 |

|

|

| 4 | 3 |

|

|

* Student-generated issues have priority over all planned activities as agenda items for group discussions.

** The group meetings often take place in informal settings (e.g., restaurant or Osler Fellow’s home); in first year, it includes a dialogue triggered by reflections following the Commemorative Service for Donors of Bodies.

*** The purpose is to provide an opportunity for students to appreciate patients’ perspectives on illness; the patients are called My First-Year Patient; students conduct the home visits in pairs and they are expected to submit written reports based on these visits.

Many of the topics included in the curriculum for the students are mirrored in the faculty development program offered to the Osler Fellows. This targeted program, called the Osler Fellowship, prepares the teachers for their role as mentors. It is described in Table 15.2.

| Year | Number of workshops | Topics | Learning activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 |

|

|

| 2 | 2 |

|

|

| 3 | 2 |

|

|

| 4 | 2 |

|

|

Aspects of the program focused on personal transformation

As previously noted, a key objective of the Physician Apprenticeship is to assist students in their “transition from layperson to physician.” Initially, this aim was not described specifically using the term “identity.” Nonetheless, there was an implicit understanding that achieving this goal involved paying attention to the evolution in students’ personal growth and maturation. The program has consistently emphasized guided reflection, including reflections on self-knowledge. The Osler Fellows have reported that they are bearing witness to the changes in their mentees’ outlooks and evolving conceptions of who they are. In retrospect, identity formation might have provided a fruitful conceptual framework with which to organize educational activities and understand their impact. In the most recent iterations of the program, including core-learning modules and the Physician Apprenticeship, there has been a shift toward an explicit discussion and consideration of professional identity formation.

An undergraduate medical education program is replete with many opportunities for examining one’s personal growth. Medical practice, by virtue of its very nature (e.g., its complexity, inescapable ambiguities, limitations, high stakes, need for discernment), represents a potent context for character development. Important way-stations in maturation can include experiences with any or all of the following: sickness, misery, plight, vulnerability, end of life, death, cadavers, responsibility, abandonment, dignity, fear, hope, blame, uncertainty, disagreement, disappointment, privacy, power, privilege, prestige, pride, poetry, mystery, and majesty. It can be said that medical education is able to provide the conditions for personal development in an accelerated fashion. The implication here is that medical schools are not required to create artificial situations in order to promote identity transformation; their responsibility is to harness and channel the ample opportunities that exist for spontaneous and guided reflection.

With respect to this latter point, cadaver-dissection programs are particularly illustrative. I find it unfortunate that some schools are abandoning them. The first day in the anatomy laboratory is indelible in the memories of generations of physicians. The first few hours of anatomy teaching around the cadaver are invariably imbued with anxiety. That anxiety is often transformed later on, once students leave the laboratory and return home (often with a residual smell of formaldehyde on the hands and flickers of body parts in the mind’s eye), into a sense of awe and a feeling that they have crossed the threshold into a new world – the world of medicine. They exit the anatomy lab as different people than they had been going in. This transformative event, as many others that occur during medical school, should not be left unexamined. Ideally, the learning that begins in the anatomy lab should continue into small groups and a commemorative service for the donors of bodies. Some experts have even explored the effects of cadaver dissection on learners’ evolving conceptions of self by inviting students into a dialogue about their dreams. Psychiatrist Eric Marcus has analyzed medical students’ dreams; he has found that nightmares of cadavers are prominent.27 His outcome data suggest that dreams can reveal salient aspects of students’ identification with patients and doctors in unique and distinct phases of professionalization.

Medical teachers can use a variety of theoretical anchors in structuring their conversations with students about critical events such as cadaver dissection or the first contact with death. The concept of liminality may be useful. Liminality relates to the phases that a person traverses in rites of passage, in transitions from one state, position, or status to another.28,29 The three phases are separation, transition (or limen), and incorporation. The liminal phase is marked by intense demands on the emotional state and, if traversed successfully, culminates in the incorporation of new personae. The concept may be applicable to undergraduate medical education, particularly when students are faced with new and emotionally charged situations, such as finding themselves in the antechamber of a sickroom with a person at the end of life, in the birthing room, with a person undergoing a cardiac arrest, or at the White Coat Ceremony. It has guided the selection of events we consider ripe for conversations focused on the “self.” There is a focus on experiences, particularly “first-time” events that may include a transitional (liminal) phase and that have an inherent potential for the incorporation of new personae. Students frequently recount instances in which they catch themselves acting like a doctor, feeling like a doctor, thinking like a doctor, talking like a doctor, or seeing like a doctor. Discussion prompts intended to elicit such reflections are presented in Table 15.3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree