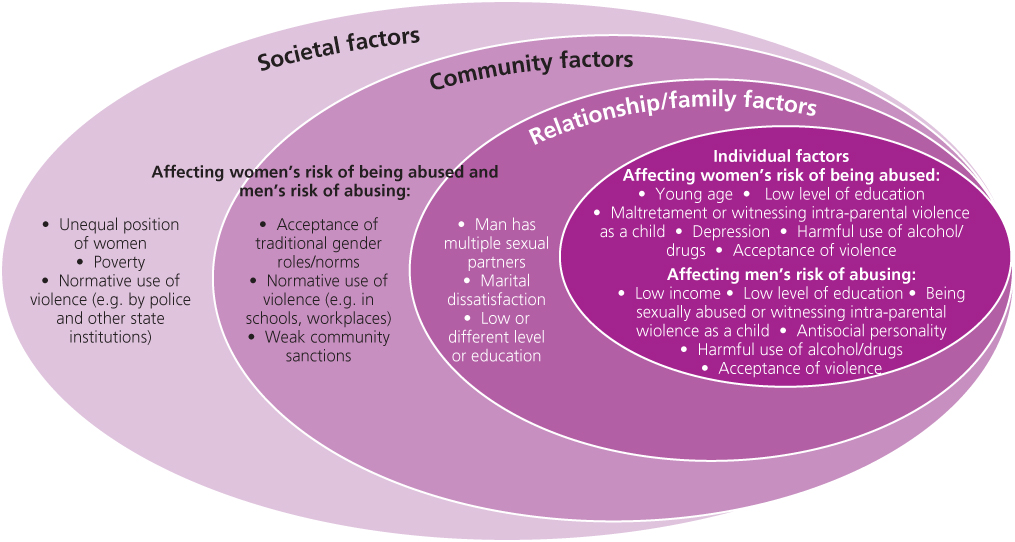

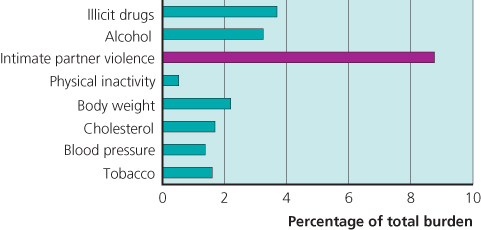

Chapter 1 This chapter outlines the epidemiology of gender-based violence in the UK and internationally in terms of prevalence, community vulnerability and health impact. It concludes with reflections on why it remains so hidden from doctors and other clinicians and the need for robust research on effective health care responses. In the UK, domestic violence is defined as any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between people aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members, regardless of gender or sexuality. This can encompass, but is not limited to, the following types of abuse: Sexual violence is a major component of domestic violence, often co-occurring with other forms of abuse, and includes sexual abuse from carers, strangers, acquaintances or friends. It is defined as any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comment or advance, attempt to traffic, or other act directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting. Gender-based violence is not confined to domestic and sexual violence. It includes: The World Health Organization (WHO) definition of gender-based violence explicitly includes its impact: ‘…[it] is likely to result in physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women…’ As discussed later in the chapter and elsewhere in this book, the health impacts are substantial and often persistent. Gender-based violence is best understood in terms of the ecological model presented in Figure 1.1, which highlights factors at all levels from the societal to the individual. Figure 1.1 Factors associated with violence against women. Source: WHO 2012 Understanding and addressing violence against women: overview. Reproduced by permission of the World Health Organization. Globally, men are more likely to die violently and prematurely as a result of armed conflict, suicide or violence perpetrated by strangers, whereas women are more likely to die at the hands of someone close to them, on whom they are often economically dependent. In much of the world, prevailing attitudes justify, tolerate or condone violence against women, often stemming from traditional beliefs about women’s subordination to men and men’s entitlement to use violence to control women. The Crime Survey for England and Wales (formally known as the British Crime Survey) is the most reliable source of community prevalence estimates of domestic violence and sexual violence in the UK. The 2011–12 survey reports lifetime partner abuse prevalence of 31% for women and 18% for men; 7 and 5% respectively had experienced abuse in the previous 12 months. The definition of partner abuse includes nonphysical abuse, threats, force, sexual assault or stalking. The Crime Survey for England and Wales also measures nonpartner domestic violence (termed ‘family abuse’), reporting a lifetime prevalence of 9 and 7% for women and men, respectively. The starkest gender difference in prevalence revealed by the Crime Survey for England and Wales is for sexual assault: 20 and 3% lifetime prevalence for women and men, respectively, although these figures include assaults by partners, ex-partners, family members or any other person. A more detailed examination of nature of physical abuse incidents recorded in 2001 also shows a greater gender asymmetry than the headline prevalence figures. Women, as compared to men, were more likely to sustain some form of physical or psychological injury as a result of the worst incident experienced since the age of 16 (75 vs 50% and 37 vs 10%, respectively), and more likely to experience severe injury such as broken bones (8 vs 2%) and severe bruising (21 vs 5%). Moreover, 89% of those reporting four or more incidents of domestic abuse were women. Data reported in 2010 showed that the majority of violent incidents against women are carried out by partners/ex-partners/family members (30%) or acquaintances (33%) rather than by strangers or as part of mugging incidents (24 and 19% respectively). In contrast, the majority of incidents against men are categorised as stranger victimisation or mugging (44 and 19%, respectively, vs 6% domestic and 32% acquaintance, mirroring the international data on murder discussed earlier). The Crime Survey for England and Wales module on sexual assault reported that 2.5% of women and 0.4% of men aged 16–59 had experienced a sexual assault (including attempts) in the previous 12 months. It also showed that 0.6% of women and 0.1% of men had been the victim of a serious sexual assault in the year prior to interview. It did not distinguish between sexual violence as part of domestic violence and that perpetrated by a friend or stranger. The WHO multicountry study conducted in 2000–03 estimated the extent of physical and sexual intimate partner violence against women in 15 sites across 10 countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, Japan, Namibia, Peru, Samoa, Serbia and Montenegro, Tanzania and Thailand). This study, involving 24 000 participants aged 14–59 years and using standardised survey methods, is the most robust comparison between countries conducted to date, although figures do not represent national prevalence rates as the samples were based in specific rural or urban settings. The reported lifetime prevalence of physical and/or sexual violence for ever-partnered women varied from 15 to 71%; 12-month prevalence rates varied from 4 to 54%. The percentage of ever-partnered women in the population who had experienced severe physical violence ranged from 4% in Japan (city) to 49% in Peru (province). The proportion of women reporting one or more acts of their partner’s controlling behaviour (including isolation from family and friends and having to seek permission before seeking medical treatment) ranged from 21 to 90%. These wide-ranging rates may reflect cultural differences in the normative level of control in intimate relationships. However, the finding that women across all sites who suffered physical or sexual partner violence were substantially more likely to experience severe controlling behaviours compared to nonabused women concurs with the view that coercive control is a defining feature of interpersonal violence, irrespective of culture. Moreover, the WHO study revealed consistent health consequences supporting their reference to impact in the definition of interpersonal violence. The WHO multicountry study also measured health status, in order to assess the extent to which physical and sexual violence were associated with adverse health outcomes. The survey focused on general health and disabling symptoms, and found significant associations between lifetime experiences of interpersonal violence and self-reported poor health and specific health problems in the previous 4 weeks: difficulty walking, difficulty with daily activities, pain, memory loss, dizziness and vaginal discharge. The increased risk varied by symptom, ranging from 50 to 80%. The first burden-of-disease analysis was conducted in Australia, reporting that interpersonal violence contributed 8% of the total disease burden in women aged 15–44 (3% in all women) and was the leading contributor to death, disability and illness for that age group, ahead of higher-profile risk factors such as diabetes, high blood pressure, smoking and obesity (see Figure 1.2). Figure 1.2 Top risk factors contributing to the disease burden in women aged 15–44 years in Victoria, Australia. Data from Vos et al. (2006). All studies of maternal mortality find that a substantial proportion of deaths result from assault by a partner. There are consistent findings of lower-birthweight babies for women who reported physical, sexual or emotional abuse during pregnancy. Other adverse pregnancy outcomes such as miscarriage and stillbirth may be associated with violence in pregnancy, although the associations are less consistent across studies. Gynaecological symptoms, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and urinary tract infections (UTIs) are increased two- to threefold in women experiencing domestic and/or sexual violence (see Chapters 16 and 17). Injuries vary from minor abrasions to life-threatening trauma. While there can be overlap between injuries resulting from interpersonal violence and injuries from other causes, the former are more than 20-fold more likely to involve trauma to the head, face and neck. Multiple facial injuries are suggestive of interpersonal violence rather than other causes. The most specific for interpersonal violence include zygomatic complex fractures, orbital blow-out fractures and perforated tympanic membrane. Blunt-force trauma to the forearms should also raise suspicion of interpersonal violence, suggesting defence wounds (see Chapters 12 and 13). Common presenting complaints and chronic physical conditions are more likely in women who have experienced domestic violence (Box 1.1). In one US study, women who experienced intimate-partner violence after controlling for potential confounders such as age, race, income and childhood exposure to intimate-partner violence, had an increased risk of a wide range of debilitating complaints (see Chapters 3, 7 and 11).

The Epidemiology of Gender-Based Violence

OVERVIEW

What are domestic violence and sexual violence and why are they gender-based?

Prevalence in the UK

Domestic violence internationally

Health impacts

Disease burden

Reproductive health problems

Injuries

Primary care

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine