INTRODUCTION

Ms Avery Jones shuffles through the magazines in the waiting room, looking for one she has not yet read. She recently lamented to her grandson that these days she seems to spend more time sitting in medical offices than doing anything else. She is an 82-year-old woman who has lived most of her life as a committed elementary school teacher. She is now retired, widowed, and carries a long list of medical diagnoses, including congestive heart failure (CHF), atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), osteoporosis, arthritis, and chronic kidney disease. She regularly sees her primary care provider (PCP), her cardiologist, her pulmonologist, and a nephrologist. She is prescribed a total of 12 medications, some of which are taken twice per day. She has to pay a few hundred dollars out-of-pocket each month for her medications, which places a significant strain on her fixed retirement budget. Unbeknownst to her, some of her brand-name prescriptions have effective, cheaper generic alternatives readily available, which would save her more than a hundred dollars each month.

Today she is scheduled to get an echocardiogram that was ordered by her pulmonologist to assess her chronically worsening shortness of breath. As they place the ultrasound probe on her chest to start the echocardiogram, she realizes that this is the exact same test that she had undergone a few weeks ago, when it was ordered by her cardiologist to “check on her CHF.” It occurs to her now that she was never told the results of that test. Her multiple physicians use different electronic medical record systems (in fact, her pulmonologist still uses paper charts), and they never seem to know what tests the other has ordered. One time she asked her nephrologist why she needed to have blood work done when she had just had blood drawn a few days prior by her PCP, and she was told that it was “better to just have it done here again so that it is in our system.”

At her last cardiology appointment her cardiologist told her that she may need a pacemaker with an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (AICD). He warned that without it she could possibly “die from a sudden heart arrhythmia.” This worried her a great deal; however, when she mentioned this to her PCP he just shrugged and told her that she didn’t need this done because her “QRS is not yet wide.” She does not know what this means but her doctor seemed to be in a rush and so she didn’t ask him to clarify. She trusts both her PCP and her cardiologist dearly and is not sure what she is supposed to do.

Healthcare in the United States is fraught with complexity, fragmentation, inefficiency, unexplained variation, and waste. In order to navigate this complexity in ways that make care more affordable, safe, and convenient, patients and their caregivers will need to understand how to deliver and receive high-value care. This will require understanding the origins and root causes of our health system shortfalls, being able to recognize existing sources and types of waste, and learning new methods of delivering care. We have written this book for clinical caregivers and focus our attention on topics of direct relevance to those who provide clinical care.

High-value care typically refers to maximizing the “quality divided by cost” equation—or, in other words, producing the best health outcomes and patient experiences at the lowest cost (see Chapter 4).1-3 Despite the seemingly simple and, perhaps, cold appearance of this definition, it is important to realize that there are many intricacies to best capture health outcomes and costs in a way that truly matters to all players in the healthcare system, including, most importantly, our patients. While clinicians may innately focus on issues related to overuse such as the avoidance of unnecessary antibiotics, patients may view the creation of value solely in terms of an enriched experience in the way they receive care.4 It is vital that neither of these goalposts gets overlooked in our quest to improve the overall value of healthcare delivered in our country. This book will aim to explore healthcare value from many different perspectives, often grappling with real tensions between the many stakeholders in our system. Ultimately, however, our goal is to provide tools for clinicians to better deliver the best possible care at lower costs.

As bleakly illustrated by Ms Jones’ situation, the current healthcare system infrequently delivers on this promise. Ms Jones’ care demonstrates the all-too-common scenario of unnecessary and redundant tests, ordered by well-meaning but inadequately informed clinicians, working in disconnected systems that do not effectively communicate. The effect of these problems is care that is less convenient, safe, humanizing, and affordable for Ms Jones. As she sits in a darkened examination room, wearing a thin cotton gown, sacrificing her time to receive a test that she did not need, she can take little comfort in the fact that she is not alone: up to one-third of healthcare may not actually make patients healthier.5 And among Medicare patients, around half of echocardiograms, imaging stress tests, pulmonary function tests, and chest computed tomography scans are repeated within 3 years.6 By some estimates, more than 40% of services delivered to Medicare patients provide minimal clinical benefit, thus are considered low-value care.7

Ms Jones was also given conflicting recommendations without the knowledge or tools to make an appropriate decision. Her physician recommended an invasive treatment (an AICD) that may not actually benefit her. In fact, as many as 22% of AICDs—which are pacemakers that are implanted into the chest wall and have the ability to shock patients’ hearts directly if the machine senses specific dangerous heart rhythms—are inserted in circumstances that are counter to the recommendations of professional society guidelines.8

All of this waste and inefficiency in the current healthcare system is astounding, and hardly defensible.

As the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently pointed out5:

“If banking were like healthcare, automated teller machine (ATM) transactions would take not seconds but perhaps days or longer as a result of unavailable or misplaced records.

If home building was like healthcare, carpenters, electricians and plumbers each would work with different blueprints, with very little coordination.

If shopping was like healthcare, product prices would not be posted, and the price charged would vary widely within the same store, depending on the source of payment.

If automobile manufacturing was like healthcare, warranties for cars that require manufacturers to pay for defects would not exist. As a result, few factories would seek to monitor and improve production line performance and product quality.

If airline travel were like healthcare, each pilot would be free to design his or her own preflight safety check, or not to perform one at all.”

This book will outline the emerging concept of value in healthcare, delineate areas of current medical waste and unsustainable costs of care, and provide evolving tools and strategies to improve the medical care that is delivered in the United States.

A LOT OF BUCKS, NOT A LOT OF BANG: THE HEALTHCARE COST AND QUALITY CRISIS

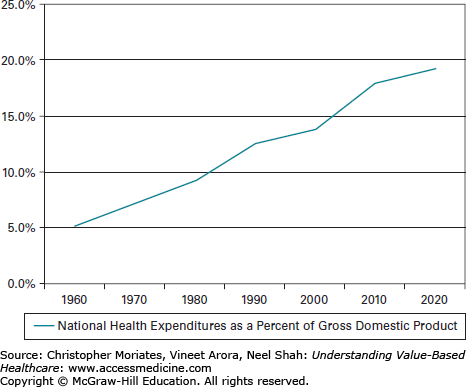

In the United States, healthcare costs have exploded over the last few decades. Approximately $2.5 to $3 trillion is spent annually in the United States on healthcare, equaling nearly 18% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2011 (Figure 1-1).9 The real issue is that despite spending more than anywhere else in the world, by a wide margin, our outcomes are actually subpar. The United States “ranks at or near the bottom in both prevalence and mortality for multiple diseases, risk factors, and injuries.”10

Figure 1-1.

National health expenditures as a percentage of gross domestic product. (Data from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary. National Health Expenditures. 2013. http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. Accessed July 14, 2013.)

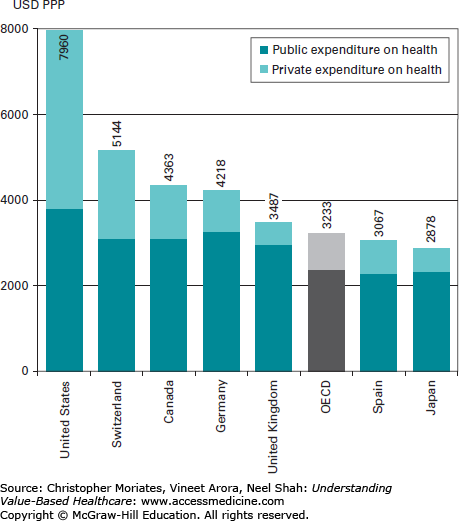

Perhaps the easiest and most relevant comparison is that to our closest neighboring country to the north. Total health spending per capita in the United States is 82% more than in Canada ($7960 vs $4363 per year, in 2009)11 (Figure 1-2), yet Americans are not any healthier. In 2000, the World Health Organization ranked the health systems of its 191 member states.12 Canada ranked 30th overall. The United States was 37th.

The Commonwealth Fund has created a health system scorecard that includes 42 performance indicators for comparing national spending rates with domestic and international quality benchmarks. In 2011, the US health system scored 66 out of 100.13 In school terms, this is a failing grade. Put bluntly, by most measures the United States is spending a lot of bucks on healthcare, but unfortunately not getting a lot of bang.

From a national health policy perspective, this is seen as a large opportunity for improvement in many ways, including how clinicians practice. For example, according to Stanford health services researcher Dr Arnold Milstein, if the average clinician in the United States practiced the way the best clinicians practice (in terms of health gained per dollar spent), our per capita spending might drop overnight by 15% to 30%.14

Although clinicians may increasingly recognize an ethical duty to address societal healthcare spending (see Chapter 6), arguments focused on the national GDP may not be the most compelling to those on the frontlines of everyday patient care. It is not that the statistics we just cited do not draw gasps of horror. They do. Clinicians understand that the exponentially growing trend lines with numbers in the trillions foretell a bleak national financial future. However, many walk away feeling uninformed about how to really change their individual practice. This may be due to the fact that healthcare providers do not go to medical or nursing or pharmacy school to treat the national GDP. They are instead appropriately passionate about treating the individual patients sitting in front of them. However, as discussed below, healthcare costs and wasteful spending do indeed affect individual patients. The financial harm to patients and their families can be substantial,15-17 and clinicians can take responsibility for helping alleviate this problem.18 Part of the challenge will be to reframe cost conversations that are typically abstracted to the population level within the clinician-patient relationship.

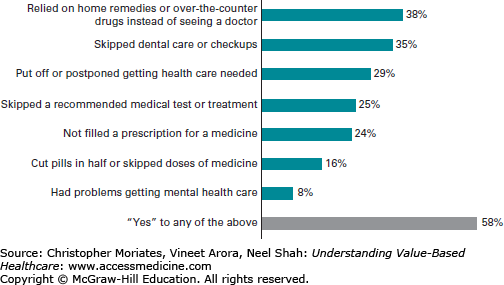

Lack of money to pay for medical bills and medications has consistently topped the list of financial concerns for Americans on the monthly Consumer Reports index survey.19 This has led approximately half of all patients to take steps to decrease their out-of-pocket costs, many of which could be dangerous (Figure 1-3).19,20

Medical bills are now a leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States,21,22 and increasingly medical insurance does not necessarily protect patients from the high costs of medical care. More Americans than ever before are now enrolled in high-deductible insurance plans (see Chapter 2). At the same time, many routine health services are arbitrarily expensive, meaning that seemingly simple decisions that physicians make about testing could directly lead to thousands of dollars in out-of-pocket costs.17,23 Even among Medicare-covered patients, the out-of-pocket costs can be astounding. In 2008, it was found that during the last five years of life, personal expenditures averaged $38,688 for individuals, and $51,030 for couples in which one spouse died.24 Incredibly, it isn’t only those unlucky enough to get sick that are suffering from high healthcare costs. Skyrocketing insurance premiums are too expensive for most Americans to afford (Chapter 2).25 In 2011, the annual premium for employer-sponsored family health coverage cost $15,073, a large burden even for middle-class families.26 This strain on household budgets can cause further erosion of personal health, and clearly leeches resources from other imperatives of daily living.

Since 2009, we have collected (via the Costs of Care Essay Contest, described in Chapter 5) more than 400 personal accounts from physicians, nurses, and patients from all over the United States that illustrate the financial and physical harms that result from the current healthcare system. These stories also present many high-yield opportunities for caregivers to improve the value of care delivery. Some of these first-person accounts are included throughout this book as “Story From the Frontlines,” to give voice to the many that are personally affected by the issues in this book, and to regularly remind all of us of the real-life high stakes at play.

HEALTHCARE WASTE

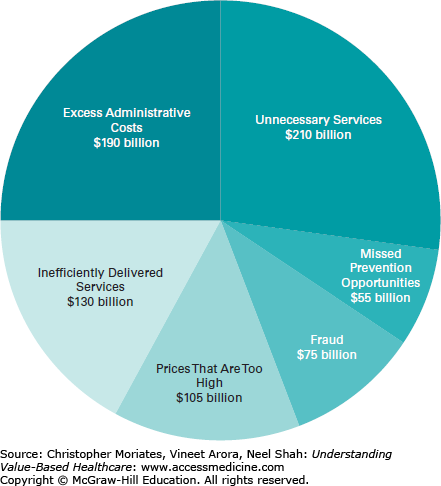

“In very large measure, improving care and reducing waste are one and the same thing,” said Dr Donald Berwick, founder of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and former administrator for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).27 A study by Dr Berwick and RAND policy analyst Dr Andrew Hackbarth estimated that approximately $476 to $992 billion is wasted in US healthcare annually.28 Around the same time, the IOM independently placed their own estimate squarely in the center of this range, at $750 to $765 billion.5,29 This waste represents up to more than 30 cents on every healthcare dollar spent. The effect on taxpayer funds is substantial, with at least $166 to $304 billion of Medicare and Medicaid spending squandered each year.28

Warren Buffett, the famous American businessman, investor and philanthropist, has likened healthcare costs to “a tapeworm eating at our economic body.”30 National healthcare expenditures, particularly those that are considered waste, divert major resources from other important domestic priorities, such as education, infrastructure (roads, railroads, and bridges), basic research, and other public goods. It drags down our global competitiveness in business, and thwarts social programs to support small businesses. Indeed, healthcare waste is detrimental at the individual, family, community, state, and national levels.5

There are multiple contributors to healthcare waste. Using the categories recognized by the IOM,5 these include

Unnecessary services (those that add to expenses without improving health)

Inefficient care due to systems errors and failures of coordination

Prices that are excessively high

Excessive administrative costs

Fraud

Missed prevention opportunities

As clinicians, when looking at the IOM pie chart of healthcare waste (Figure 1-4), our eye is most drawn to that upper right quadrant where the slice for “unnecessary services” resides. This is not only because, at $210 billion, unnecessary services comprise the biggest proportion of the pie, but also because this is the area that individual clinicians have the most direct control over every day that they care for patients. Whenever a physician places pen to a prescription pad (or enters an order into a computer system), she is liable to be contributing to the $210 billion spent each year on services that do not make patients any healthier. These are medications, tests, and procedures that are not evidence-based, go outside of guidelines, and, in a minority of cases, are known to cause net harm (eg, elective back surgery in certain situations), but are done anyways.

As discussed throughout this book, the problem of overuse has become pervasive in US healthcare.31,32 Recently, this culture of overuse has become a hot topic in the medical literature,33-35 and the popular press has begun to explain the problem of overtesting and overtreatment to the public.36-38

Let’s briefly consider the example of using a computed tomography angiography (CTA) scan to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE)—a potentially life-threatening blood clot in the lungs that can be difficult to diagnose from symptoms alone. The story of CTA scans and PEs demonstrates the complicated relationships between overuse, overdiagnosis, technology, and the lack of a sufficient evidence-base to guide decisions.

While some patients with PE dramatically suffer cardiovascular collapse and acute heart failure, others with ultimately clinically significant PEs may present with very vague complaints and lack clear objective findings on examination.39 In fact, the possibility of an underlying PE is discussed nearly daily on medicine and surgical hospital rounds. Despite this focus, there are many gaps that remain in our knowledge for appropriately diagnosing and treating PE. This has led to PE being called “a metaphor for medicine in the evidence-based medicine era.”40 At first glance this sounds like a compliment since most modern clinicians worship at the altar of “evidence-based medicine,” but Dr Vinay Prasad and his colleagues from Northwestern University and colleagues warn that they actually consider PE a metaphor “not because it represents a great success, but because it captures all the complexity of medicine in the evidence-based era.”40

For many years the incidence of PE was stable at about 62 cases per 100,000 population.41 Then in 1998, CTA became widely utilized for the diagnosis of PE. Over the next 8 years, the number of PEs diagnosed nearly doubled. However, despite these rapidly increasing number of PEs found and treated, the effect on mortality was very small. We were diagnosing and treating twice as many PEs, but we weren’t really saving many more lives. This pattern is consistent with overdiagnosis.41

It would be one thing if we simply weren’t making much of a difference, but in fact overdiagnosis frequently can lead to significant harms.42 As we began treating more patients for PEs with blood thinners, or anticoagulants, the rate of major bleeding complications increased rather dramatically—from 3.1 to 5.3 per 100,000.41

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree