The Concept of Normalcy

Within Western medicine, physically ill people approach medical helpers in a manner much different from the psychologically ill. Physically ill people bring sick bodies to physicians; emotionally ill people bring sick souls to psychotherapists. Differences in these two forms of helping are visible even in the language; the person in need of medical help is always a “patient,” while the person in need of psychotherapy is often a “client.” Each form of helping has a particular way of approaching the person needing help. Medical patients are treated, taken care of, and made better by the doctor. Psychotherapy clients must be actively engaged in their healing.

–Carol Becker (b. 1942).

Most people think of themselves as “normal,” and investigators often want to enroll “normal” volunteers into a clinical trial. We assume we know what normal means, but in fact, the entire concept of normalcy is both vague and complex. This chapter explores various aspects of the concept of normality and attempts to clarify a number of issues that arise in the planning, conduct, and interpretation of clinical trials.

Once a more clear understanding of the concept of normalcy has been achieved, clinical research can focus on studying the phenomenon and its relationship to disease, medical treatments, and an individual’s quality of life. Protocol authors can use some concepts described in this chapter to better characterize and measure what is intended by the term normal in their inclusion criteria.

DEFINITIONS AND DESCRIPTIONS

Normalcy

The concept of “normal” has diverse definitions depending on the context and perspective(s) being used to consider the term. For example, the dictionary defines normal as “not deviating from an established norm or standard.” In biology, normal generally means “unaffected by any particular infection or experimental treatment.” Psychiatrists use normal to mean “free from mental disorders.” An operational definition is “the usual state of how one feels and acts physically, psychologically, socially, spiritually, and economically when one perceives himself to be not ill.” To this, we might add that others in society also consider the person not to be ill.

Another aspect of being normal is that the person is in his usual state of health or well-being, even if he has a major illness or even if he has many outward signs of chronic sickness with or without symptoms.

Normalcy is judged in relation to current or previous states of feeling and acting and also in relation to how a person views other so-called normal people. In extreme cases, people may change their frame of reference about what is normal about their situation because of an external crisis in their environment, such as war or famine or being in a concentration camp, or because of an internal personal crisis, such as diagnosis of or recovery from a serious illness.

Types of Normalcy

While the perspective of a person’s normalcy could be from the person himself or herself, the physician, friends, family, or others, only the first two are considered here because they are the ones that usually relate to a clinical trial.

In a trial setting, a patient usually is able to qualify as a “normal” volunteer even when one or more laboratory values or clinical signs lie outside the normal range for that analyte or sign. It is clear that the definition of normal does not require that every laboratory test and clinical sign be definitely within the normal range. If that were the definition of normal, there would be very few normal people in society. Therefore, the first broad definition of normalcy is in relation of the subject to others in that society.

A patient who is not a “normal volunteer” in a clinical trial but has a disease that is being treated in a clinical trial may characterize his reactions to a drug in terms of whether he feels “normal” (i.e., about the same as immediately prior to the treatment he is given in the trial) or he may be asked to compare his state of being while receiving treatment to that immediately prior to the last dose of drug taken, to his state a week before (or to another period).

A physician assesses a volunteer as normal if he passes all screening tests and is allowed to enroll in the trial. A physician who approaches and interviews a patient whom he knows may notice signs, symptoms, affect, or other clues that the patient is not in his normal (i.e., usual) state of health and, therefore, question the patient carefully about any adverse events that may be experienced. These two examples indicate two different definitions of normal. The first is to define normal in comparison to the population as a whole and the second is in terms of one’s own state of health, even if the person is not considered normal by the first definition.

Subnormalcy and Supernormalcy

The concepts of subnormal and supernormal are in comparison to a person’s own standards of being normal. It is not meant as a comparison of one’s self with a super athlete or to one’s self at a much earlier stage in one’s life.

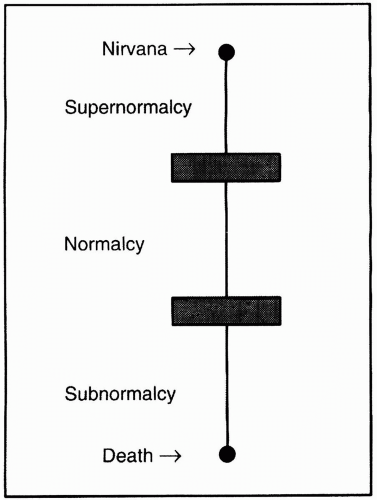

People often describe their own state as being either better or worse than it generally is at the present time. These states are referred to as “supernormal” and “subnormal.” Clearly, there is a gradient from being or feeling supernormal to normal to subnormal, but these concepts are more complex than a simple linear continuum would imply (Fig. 79.1).

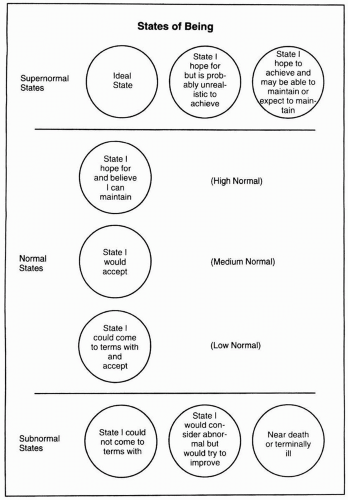

The states of supernormalcy, normalcy, and subnormalcy may be visualized as a circle (Fig. 79.2). These states overlap, and selected types are shown in Fig. 79.3. Illness is a subnormal state, and it may accompany either of the other states at the same time (i.e., one can feel emotionally “high” after receiving particularly important news, which may last for days or weeks, but at the same time, one may have a serious illness). The characteristics of supernormalcy vary greatly among individuals, but some of the more common characteristics are listed in Table 79.1. A few of the methods used to approach or attain supernormalcy are listed in Table 79.2.

An individual with bizarre behavior or obvious physical problems may sometimes be called “normal” by others because the term normal may be used to mean “normal for him or her.”

USING THE CONCEPT OF NORMALCY IN CLINICAL TRIALS

Tests for Normalcy

There is no standardized global test to determine whether or not a person is normal. Medical disciplines have focused on the study and treatment of disease, illness, problems, syndromes, and other abnormal states. Clinical trials usually are designed to evaluate prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of these abnormal states. The primary goal of medical intervention is to bring patients from a state considered abnormal toward a state that achieves or approaches normalcy.

A physician who assesses a patient may describe normalcy in objective and/or subjective terms (Fig. 79.4). For instance, abnormal heart sounds may be described as 1+, 2+, 3+, or 4+ abnormal. Laboratory values may be described in terms of any

arbitrary scale to illustrate the degree of abnormality. Subjective parameters such as a person’s affect may be described in Likert scale categories that indicate levels of abnormality (e.g., mildly abnormal, moderately abnormal, markedly abnormal).

arbitrary scale to illustrate the degree of abnormality. Subjective parameters such as a person’s affect may be described in Likert scale categories that indicate levels of abnormality (e.g., mildly abnormal, moderately abnormal, markedly abnormal).

Table 79.1 Characteristics often reported by people who view themselves as “supernormal” | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 79.2 Methods people use to move toward supernormalcya | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree