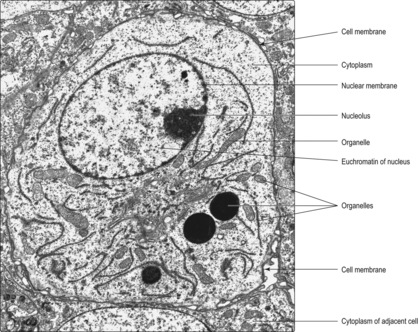

Cell membrane

The cell membrane is semi-permeable and allows inward and outward passage of selected substances. It also forms an essential barrier to the exterior and a boundary for the internal structure of the cell. It may be involved in attachments to adjacent cells (see below) and in recognition and communication within and outside the cell. Within, it may communicate with its cytoplasm and some signals may pass to the nucleus. Outside, it may communicate with other ‘self’ cells, both normal and abnormal (e.g. tumour cells or virally infected cells). Many cells interact, via their cell membrane, with microbes, and various molecules foreign to the body and a variety of cellular activities are stimulated or inhibited as a result.

Nucleus and nucleolus

The nucleus contains the vast majority of the DNA of the cell. The DNA is the hereditary material that has the genetic code expressed in a double strand of DNA in each chromosome. (Chromosomes contain proteins as well as DNA.) The number of chromosomes in a typical cell is species specific (humans have 46). Human chromosomes comprise 22 homologous pairs and a pair of sex chromosomes (two X chromosomes in females and an X and a Y chromosome in males). One of each pair of chromosomes is derived from the mother’s oocyte and the other from the father’s spermatozoon (see, respectively,

Chapters 16 and

15). The nucleus may also contain the structural and molecular mechanisms for the synthesis of RNA in one or more nucleoli.

The nucleus is enclosed by a nuclear membrane which is formed by two plasma membranes. In places, the nuclear membrane is perforated by pores which allow transport of material to and from the nucleus. The outer nuclear membrane is continuous in places with some membranes in the cytoplasm, and molecules (e.g. proteins and RNA) travel between nucleus and cytoplasm by this route.

The appearance of nuclei varies in relation to their function. Individual chromosomes are not apparent in cells unless the cell is dividing. The nuclear material, comprising DNA, proteins and RNA, is known as chromatin and two types are described, euchromatin and heterochromatin. Euchromatin appears less dense than heterochromatin (

Figs 2.1 and

2.2). The DNA molecules in euchromatin are uncoiled and are being used as coding for RNA synthesis which, in turn, directs protein synthesis in the cytoplasm. A large amount of euchromatin in a nucleus (

Fig. 2.1) indicates that a wide variety of RNA molecules are being made (and types of protein produced as a result). In contrast, in heterochromatin the DNA molecules are coiled and condensed and appear dense. The DNA in heterochromatin is mostly inactive, i.e. not directing the synthesis of RNA.

One or more nucleoli also appear as densely stained regions in the nuclei of cells actively synthesising proteins: their position may appear central or peripheral (

Fig. 2.1). RNA molecules synthesised in the nucleolus leave the nucleus, via pores in the nuclear membrane, and are involved in organising protein synthesis in the cytoplasm.