19 The breast

Anatomy and physiology

Anatomy

The main route of lymphatic spread of breast cancer is to the axillary nodes, which are situated below the axillary vein. On average, there are 20 nodes in the axilla below the axillary vein (Fig. 19.1). These are separated into three levels by their relation to the pectoralis minor muscle. Nodes lateral to the pectoralis minor are considered level I, those beneath are classified as level II, and the nodes medial to pectoralis minor are level III. Level I nodes, which are nearest the breast, are usually affected first by breast cancer. In less than 5% of patients, levels II or III nodes are involved without level I nodes being affected. Lymph also drains to the internal mammary nodes. Occasionally, the main route of lymph drainage of a cancer is to the interpectoral nodes situated between the pectoralis major and minor muscles.

Evaluation of the patient with breast disease

Clinical examination

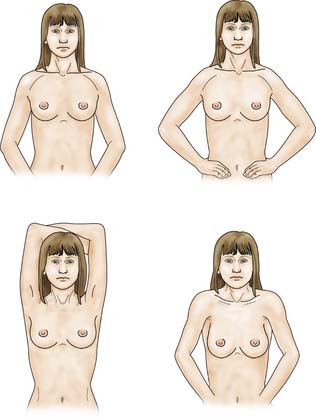

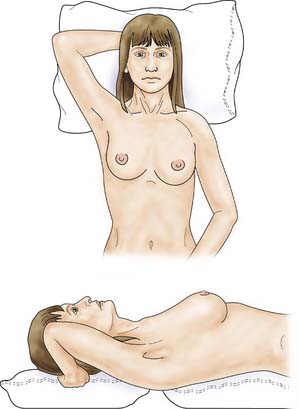

The patient is asked to undress to the waist and sit facing the examiner. Inspection should take place in good light with the patient’s arms by her side, above her head, and then pressing on her hips (Fig. 19.2). Skin dimpling or a change of contour is present in a high percentage of patients with breast cancer (Fig. 19.3). Breast palpation is performed with the patient lying flat with her arms above or under her head. All the breast tissue is examined, using the fingertips to detect any abnormality (Fig. 19.4). Any abnormal area is then examined in more detail, to determine the texture and outline of the mass. Deep fixation is assessed by asking the patient to tense the pectoralis major muscle; this is accomplished by asking her to press her hands on her hips. All palpable lesions should be measured with callipers and the size and site (using the clock) recorded in the hospital notes.

Fig. 19.3 Skin dimpling in the lower inner quadrant of the left breast associated with breast cancer.

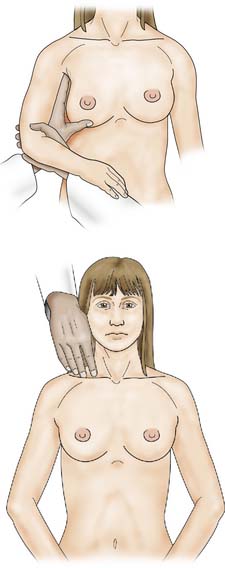

Assessment of regional nodes

Once the breast has been palpated, the nodal areas are checked (Fig. 19.5). Clinical assessment of axillary nodes is not always accurate. Palpable nodes can be identified in up to 30% of patients with no clinically significant breast disease, while up to 25% of patients with breast cancer who have no palpable nodes on examination will be found histologically to have metastatic disease in the axillary nodes. Ultrasound is better at assessing axillary nodes than clinical examination. The supraclavicular nodes are best examined from behind.

Imaging

Ultrasonography

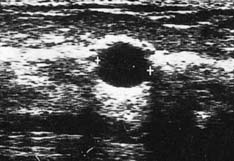

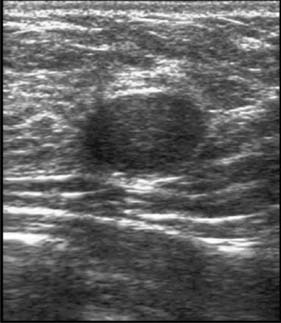

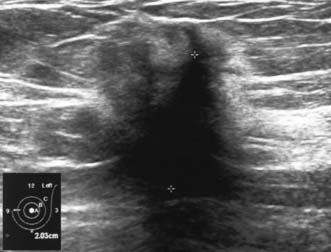

High-frequency waves are beamed through the breast and reflections are detected and turned into images. Cysts show up as transparent objects (Fig. 19.6) and other benign lesions tend to have well-demarcated edges (Fig. 19.7), whereas cancers usually have an indistinct outline and absorb sound, resulting in a posterior acoustic shadow (Fig. 19.8). Ultrasound is also used to assess axillary nodes in patients with breast cancer. Where nodes are enlarged or the cortex of the node thickened, fine needle aspiration cytology or core biopsy should be performed to establish whether nodal metastases are present.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

This is an accurate way of imaging the breast. It has a high sensitivity for breast cancer and may be of value in demonstrating the extent of both invasive and non-invasive disease. It is particularly useful in the conserved breast to determine whether a mammographic lesion at the site of previous surgery is due to scar or to recurrence. It is currently used as a screening tool for high-risk women between the ages of 35 and 50 (EBM 19.1). MRI is the optimum method of imaging breast implants and detecting implant leakage or rupture.

Fine needle cytology and biopsy

Core biopsy

Several cores are removed from a mass or an area of microcalcification by means of a cutting needle technique after injection of local anaesthetic (Fig. 19.9). A 14-gauge needle combined with a mechanical gun produces satisfactory samples and allows the procedure to be performed single-handed. Core biopsy can be performed using palpation to guide biopsy but is most successful when image guidance is employed (ultrasound for mass lesions, stereotactic biopsy for calcifications which are usually impalpable). Vacuum-assisted core biopsy devices allow several large cores to be removed without withdrawing the needle from the breast, and have some advantages when biopsying areas of indeterminate microcalcification detected on screening.

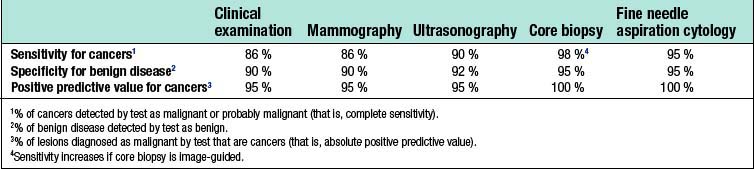

Accuracy of investigations

False-positive results occur with all diagnostic techniques. The sensitivity of clinical examination and mammography varies with age, and only two-thirds of cancers in women under 50 years of age are considered suspicious or definitely malignant on clinical examination or mammography (Table 19.1). Image-guided core biopsy is the most accurate and efficient of the various techniques used to diagnose breast masses.

Disorders of development

Most benign breast conditions occur during development, cyclical activity or involution, and are so common that they are best considered as aberrations rather than true disease (Table 19.2).

Table 19.2 Aberrations of normal breast development and involution

| Age (years) | Normal process | Aberration |

|---|---|---|

| < 25 | Breast development Stromal Lobular | Juvenile hypertrophy Fibroadenoma |

| 25–40 | Cyclical activity | Cyclical mastalgia Cyclical nodularity (diffuse or focal) |

| 30–55 | Involution | |

| Lobular | Palpable cysts | |

| Stromal | Sclerosing lesions | |

| Ductal | Duct ectasia |

Juvenile hypertrophy

Uncontrolled overgrowth of breast tissue occurs occasionally in adolescent girls, whose breast development initially begins normally at puberty and is followed by rapid breast growth. These changes are usually bilateral, but may be limited to one breast or part of one breast. This process is often referred to as virginal or juvenile hypertrophy (Fig. 19.10). However, it is not hypertrophy, as there is an increase in the amount of stromal tissue rather than in the number of lobules or ducts. This excessive growth is an aberration rather than a true disease, and presenting symptoms are large breasts and pain in the shoulders, neck and back or under the bra straps. Treatment is by reduction mammaplasty.

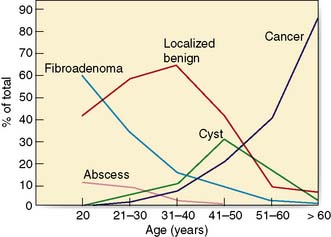

Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenomas are classified in most texts as benign tumours, but are best considered as aberrations of development rather than true neoplasms. The reasons are that fibroadenomas develop from a whole lobule rather than from a single cell, and show hormonal dependence similar to that of normal breast tissue, lactating during pregnancy and involuting in the perimenopausal period. Fibroadenomas are most commonly seen immediately following the period of breast development and growth in the 15–25-year age group (Fig. 19.11). They are usually well-circumscribed, firm, smooth, mobile lumps, and may be multiple or bilateral. Although a small number of fibroadenomas increase in size, most do not and over one-third become smaller or disappear within 2 years. Fibroadenomas have a characteristic appearance with easily visualized margins on ultrasound (Fig. 19.7). Large or giant fibroadenomas (> 5 cm) are infrequent but are more commonly seen in women from certain African countries. Occasionally, a fibroadenoma in an adolescent girl undergoes rapid growth, a condition called juvenile fibroadenoma (Fig. 19.12). Once a diagnosis of fibroadenoma has been established on core biopsy, options for management in lesions measuring less than 4 cm include reassurance with no follow up needed or excision; fibroadenomas over 4 cm in diameter should be excised to ensure that phyllodes tumours are not missed (see below). A carcinoma arising in a fibroadenoma is extremely rare. Patients with simple fibroadenomas are not at significantly increased risk of developing breast cancer.

Disorders of cyclical change

Nodularity

Lumpiness and nodularity in the breast can be diffuse or focal. Diffuse nodularity is normal, particularly premenstrually. In the past, women with lumpy breasts were regarded as having fibroadenosis or fibrocystic disease, but this diffuse nodularity is not associated with any underlying pathological abnormality and so these terms are inappropriate. Focal nodularity is a common cause for women seeking medical advice and is seen in women of all ages (Fig. 19.11). Patients with benign focal nodularity often report that the lump fluctuates in size in relation to the menstrual cycle. Breast cancer should be excluded by imaging +/- core biopsy in women with persistent localized asymmetric areas of nodularity, as breast cancer in younger women often presents as nodularity rather than a discrete mass.

Disorders of involution

Palpable breast cysts

Approximately 7% of women in developed countries develop a palpable breast cyst at some time in their life. Cysts constitute 15% of all discrete breast masses. They are distended, involuted lobules and are most frequently seen in the perimenopausal period (Fig. 19.11). Clinically, they are smooth discrete lumps that can be painful and are sometimes visible. Mammographically, they have characteristic haloes and are easily diagnosed by ultrasonography (see Fig. 19.6). Symptomatic palpable cysts are treated by aspiration and, provided the fluid is not blood-stained, it is discarded. Cysts that contain blood-stained fluid require excision to exclude an associated intracystic cancer. Such cancers are rare and are usually evident on ultrasound. Most cysts are asymptomatic and, following ultrasound assessment, do not need aspiration. All patients with cysts should have mammography, preferably before cyst aspiration, as between 1 and 3% will have a cancer, usually remote from the cyst, visible on mammography (Fig. 19.13). Patients with cysts have a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer, but the magnitude of this risk is not considered of clinical significance.

Duct ectasia

The major subareolar ducts dilate and shorten with age; when symptomatic, this is known as duct ectasia. By the age of 70, 40% of women have dilated ducts, some of whom present with nipple discharge or retraction. The discharge is usually cheesy and the retraction is classically slit-like (Fig. 19.14), which contrasts with breast cancer, in which the whole nipple is pulled in (Fig. 19.15). Surgery is indicated if the discharge is troublesome or if the patient wishes the nipple to be everted.

Benign neoplasms

Duct papillomas

These can be single or multiple. They are very common, and should be considered as aberrations rather than true neoplasms as they show minimal malignant potential. They can cause persistent and troublesome nipple discharge, which can be either frankly blood-stained (Fig. 19.16), or serous. Treatment comprises removal of the discharging duct (microdochectomy), which removes the papilloma (if this is the cause) and allows exclusion of an underlying neoplasm, seen in approximately 5% of women who present with a blood-stained nipple discharge.

Phyllodes tumours

Summary Box 19.1 Benign breast disease

• Is more common than breast cancer

• Can be difficult to differentiate from breast cancer

• Inappropriate treatment of benign conditions is associated with significant morbidity

• Occurs against the background of breast development (age < 25), cyclical activity (up to menopause) and involution (following the menopause)

• The only benign condition associated with a significant increased risk of subsequent breast cancer is atypical hyperplasia.

Breast infection

The principles of treating breast infection are:

• Give appropriate antibiotics early to reduce the incidence of abscess formation (Table 19.3)

• If an abscess is suspected, confirm pus is present by ultrasound or aspiration before embarking on surgical drainage

• Exclude breast cancer using imaging and core biopsy in an inflammatory lesion that is solid and that does not settle despite adequate antibiotic treatment.

Table 19.3 Antibiotics most appropriate for treating breast infections*

| Type of infection | No allergy to penicillin | Allergy to penicillin |

|---|---|---|

| Lactating and skin-associated | Flucloxacillin (500 mg 6-hourly) | Clarithromycin (500 mg 12-hourly) |

| Non-lactating | Co-amoxiclav (375 mg 8-hourly) | Combination of clarithromycin (500 mg 12-hourly) with metronidazole (200 mg 8-hourly) |

Lactating infection

Improvements in maternal and infant hygiene have reduced considerably the incidence of infection associated with breastfeeding. When infection does occur, it usually develops within the first 6 weeks of breastfeeding. Presenting features are pain, swelling, tenderness and a cracked nipple or skin abrasion. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism, although Staph. epidermidis and streptococci are occasionally implicated. Drainage of milk from the affected segment is reduced, with the resultant stagnant milk becoming infected. Early infection is treated with flucloxacillin or co-amoxiclav. An established abscess should be treated by recurrent aspiration, or by incision and drainage (Fig. 19.17). Women should be encouraged to breastfeed, as this promotes milk drainage from the affected segment. Rarely, milk flow needs to be stopped using cabergoline, a prolactin antagonist.

Non-lactating infection

Central (periareolar) infection

Treatment of periductal mastitis is with appropriate antibiotics (Table 19.3). Abscesses are managed by aspiration or incision and drainage. Infection is commonly recurrent because treatment does not remove the damaged subareolar duct(s). Following drainage of a non-lactating abscess, up to one-third of patients develop a mammary duct fistula. Recurrent episodes of peri-areolar infection require excision of the diseased duct(s) (total duct excision).

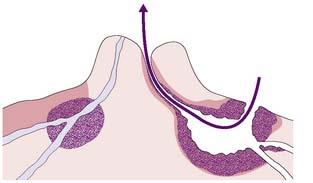

Mammary duct fistula

This is a communication between the skin – usually at the areolar margin – and a major subareolar duct (Fig. 19.18). Treatment is by excision of the fistula and diseased duct(s) under antibiotic cover.

Peripheral non-lactating abscesses

These are less common than periareolar abscesses and are sometimes associated with an underlying condition, such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, steroid treatment, granulomatous lobular mastitis or trauma. Infection associated with granulomatous lobular mastitis can be a particular problem, as there is a strong tendency for this condition to persist and recur despite surgery. Peripheral abscesses should be treated by recurrent aspiration with antibiotics (Table 19.3), or incision and drainage under local anaesthesia.

Summary Box 19.2 Breast infection

• Antibiotics should be given early to reduce abscess formation

• Hospital referral is indicated if infection does not settle rapidly on antibiotics

• If an abscess is suspected, this should be confirmed by ultrasound or aspiration

• If the lesion is solid on ultrasound or aspiration a core biopsy should be performed to exclude an underlying inflammatory carcinoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree