The Beginning of the Interview: Patient-Centered Interviewing: Introduction

You just don’t luck into things as much as you’d like to think you do. You build step by step whether it’s friendships or opportunities.

Barbara Bush

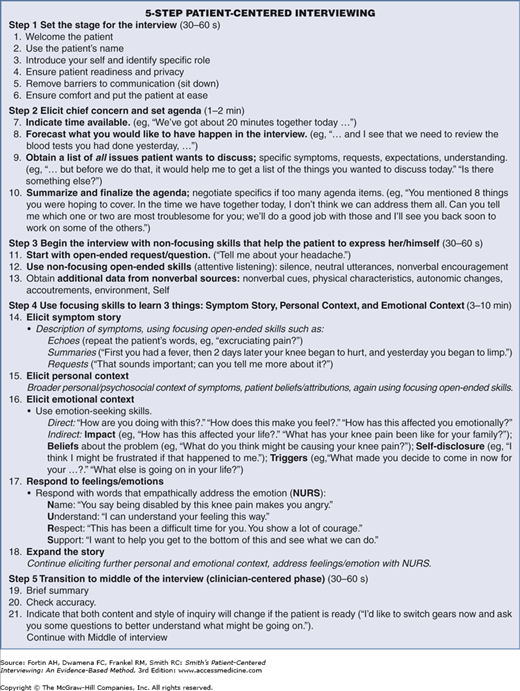

This chapter describes a user-friendly step-by-step method for the beginning of the medical interview that has been effective in many hands during the last 20 years.1–8 Your first task is to master the 5 steps and 21 substeps shown in Figure 3-1. We urge you to learn these thoroughly; to the point that they become reflexive—this is easily accomplished by studying, and then practicing them. Even though this may seem like a lot to learn, just as you learn the intricacies of cardiac physiology, this is your major task in mastering the medical interview. Using these steps and substeps will make you a more scientific and more humanistic physician—and your patients will benefit (see Appendix B for a detailed humanistic and scientific rationale for being patient-centered). To assist you, we also have developed a video that demonstrates the same skills described here: http://www.mhprofessional.com/patient-centered-interviewing (see Preface).

When first learning these steps, use them in the order presented, primarily as a learning tool. As you become more skilled, you can vary the steps and substeps to experiment as well as to adapt to specific occasions and needs. You may find that some substeps can be omitted and, in other instances, you may want to change the ordering. The steps and substeps are simply a pathway to lead you through the interview; use them flexibly to individualize and enhance your own style and the patient’s individuality.

The five steps in the beginning of the interview establish the clinician–patient relationship and encourage the patient to express what is most important to her or him. Throughout this book, an ongoing interview with “Mrs. Joanne Jones” will illustrate each step; this and other examples are derived from real patients and situations; we have changed all names and identifying information to protect the confidentiality of our patients.

Let’s first talk about some preparatory skills: setting the stage (Step 1) and determining the agenda (including the chief concern/complaint) for the interview (Step 2). These steps prepare both you and the patient for the patient-centered interviewing skills you will use in Steps 3 and 4, which is where the data-gathering and relationship-building skills you learned in Chapter 2 will be incorporated.

Setting the Stage for the Interview (Step 1)

The skills in Step 1 are simple, but often overlooked9–11 courtesies that ensure a patient-centered atmosphere. Table 3-1 lists these substeps in their usual order of use at the first meeting with a patient; appropriate adjustments are made when the patient is already known to the interviewer. These skills establish or reaffirm participants’ identities, put both the interviewer and the patient at ease, and ensure that the setting is appropriate for the interview. These preparatory steps should take no more than 30–60 seconds.

|

Maintain patient safety and hygiene by first washing your hands. Try to shake hands with the patient, but be sensitive to nonverbal cues and cultural norms that indicate that the patient may not be open to this behavior.9 For example, in Islamic culture and among some religious Jews shaking hands in a cross gender situation is viewed as culturally inappropriate. When it is not possible to shake hands, for example with very ill patients, a friendly pat on the hand or arm is equally beneficial to the relationship. You can develop some important initial nonverbal impressions about the patient from the handshake; for example, a hearty handshake suggesting a confident person, a cold sweaty palm suggesting anxiety, and the feeble handshake of someone very ill. Remember that the patient is also reading your nonverbal cues.9,12–14 Smiling; having a friendly, personable, polite and respectful demeanor; being attentive and calm; making eye contact; and making the patient feel like a priority will enhance the relationship with the patient. Alternatively, fidgeting, frequently glancing at your watch or mobile device, avoiding eye contact, or looking distracted may be interpreted negatively by the patient.

Patients are divided on how they want to be addressed.9,15 Some patients want their first name to be used when they are greeted; but others prefer either their last name or both their first and last names. We recommend that you use formal terms of address, Mr., Miss, Ms., Mrs., (using Ms. if you do not know a woman’s marital status) and the patient’s last name in your initial greeting. It is easier to go from more formal to less formal terms of address than the reverse. After formally greeting the patient, you can ask how she or he prefers to be addressed and use the preferred title/name the next time you mention her or his name. If the patient has an unusual name, you may need to ask how to pronounce it. It is sometimes useful as a way of creating a welcoming atmosphere to ask if a non-English name, for example, Rakesh, Ming, Ganady, Kwesi, has a translation into English and what it means.

When introducing yourself, be sure to match identity terms to avoid suggesting an unequal relationship.15 As with patients, use both your first and last names initially. You should not say, for example, “Hi George, I’m Dr. Smith” or “Welcome Mr. Brown, I’m Betty.” Occasionally at the beginning but more often after some time, a relationship on first-name basis may develop. After you introduce yourself, mention your official role, for example, “medical student” or “nursing student.” Medical students can use the term ‘student doctor’ or ‘student physician’ after they pass USMLE Step 1.16 However, it is not appropriate to use a professional label like “doctor,” “nurse,” “nurse practitioner” or “physician assistant” when you have not been certified to do so.

It is very common for students, particularly preclinical students, to feel uncomfortable in their first patient interviews. You may feel like an imposter, that you are intruding or being voyeuristic, or that you are not playing a meaningful role in the patient’s care. Remember that every clinician learned to interview through the generosity of patients. Patients often are quite happy to help a young clinician learn as long as you politely ask, express thanks, and understand why some patients may feel too ill to participate in this way. As a clinical student however, you are an important and legitimate member of the medical team, so you should not apologize or otherwise devalue yourself (“I’m just a student, thanks for letting me talk to you.”). The annals of medicine are replete with stories of students’ contributions to care, as they are with stories of patients deferring to students’ opinions; for example, when the resident or faculty makes a recommendation directly to the patient, the patient may say, “I’ll have to ask Ms. Burns [the student] first.” To respect patient autonomy, your supervisor should ensure that the patient has no reservations about being interviewed or cared for by a student.16

Substeps 1, 2, and 3 of Step 1 can be combined in a single statement like “Mr. George Brown? Hello, I’m Mark Burns. I’m the medical (or nurse practitioner, PA) student on the team that will be looking after you. How do you prefer to be called?”

Initially, especially in hospital settings and with very ill patients, determine if the time is convenient for the interview. Sometimes it is necessary to postpone the interview; for example, until after the patient has eaten dinner or relatives have departed; or until the vomiting from recent chemotherapy has abated. Severe pain, severe nausea, need for a medication, and a soiled bed, for example, are physical problems that must be addressed before an interview is appropriate. It is also important to monitor the patient’s circumstances for nonphysical, potentially interfering problems; for example, a patient may have lost her or his car keys in the waiting room, just received a disturbing telephone call, or be worried that the baby sitter will have to leave before she or he gets home. With all patients, it is important to determine if there are pressing needs that might require a brief delay in the interview; for example, to use the bathroom, get a drink of water. These courtesies not only help the patient directly but enhance patients’ acceptance of you as a caring professional. Once ready, some actions that will improve the patient’s readiness and privacy are shutting the door, pulling a curtain around the hospital bed or respectfully excusing a curious laboratory technician.

You may have to ask permission to turn off a noisy air conditioner or TV set, or make efforts requiring more insight such as recognizing that the patient hears best out of one ear or that she or he needs to be able to directly see the interviewer’s mouth in order to speech-read. If there is any question, you can ask the patient whether she or he can hear you well. Strategies for addressing specific communication problems are outlined in Chapter 7. Patients experience that you have spent more time with them if you sit, so do so whenever possible. Communication is optimal if you and the patient are at the same eye level.17 If you are both sitting, orienting the chairs at approximately a 90-degree angle is optimal for communication (see doc.com Module 1418). Attention to the nonverbal aspects of communication is important and is covered in more detail in Chapter 8, Section “Nonverbal Dimensions of the Relationship”. And remember, it is just as important to turn the TV you asked permission to turn off, back on!

Exam-room computing can be a potential barrier to the clinician–patient relationship.19,20 If you plan to use a computer during the interview, be sure that it is placed in a location where you can simultaneously enter and share the information with the patient. Explain to the patient that you will be taking some notes or entering information into the computer and inquire whether this is okay.21 Write or enter information in the medical chart or computer only intermittently, and not until the patient has finished speaking. When writing or entering information, pause frequently and make eye contact with the patient. We suggest that you focus on the patient and not the computer during the beginning of the interview. See Chapter 7, Section “Taking Notes and Using Computers” for more details.

Determine if anything at the immediate time is interfering with the patient’s comfort. Questions like, “Is that a comfortable chair for you?” or “Is the light bothering your eyes?” or “Can I raise the head of the bed for you?” are essential. Continue to monitor the patient’s comfort as the interview proceeds. Your task is to put the patient at ease, as much as you can. Attention to these potential barriers helps the patient and allows his/her subsequent full attention and also shows your caring and concern.

Usually there are no such interfering problems to address; nevertheless, it may be beneficial to engage in a little social conversation to put the patient at ease. You may be ready to start the interview but the patient sometimes is not and still does not know much about you. This brief conversation should have a patient focus such as, “I hope you got your car parked OK with all the construction going on around here.” With an inpatient, you can inquire about their care, get well cards the patient has received, or the food; whatever is appropriate to the patient’s situation can be briefly discussed. This allows the patient to get more comfortable with you. Hopefully, you have now established friendly atmosphere.

Obtaining the Agenda (Chief Concern/Complaint and Other Active Problems) (Step 2)

In Step 2, you will focus on the patient and setting the agenda for the interview. This fosters the patient-centered interaction to follow (Steps 3 and 4) because it orients and empowers the patient and ensures that her or his concerns are properly prioritized and addressed. Some clinicians unwittingly preclude agenda setting by saying “What brings you in today?” or “How are you doing?” Patients interpret these phrases as an invitation to tell the story of the first concern on their list, rather than generating a list of concerns. This often leads clinicians to miss important information and fail to meet patients’ expectations.22–26 Setting an agenda usually takes little time, improves efficiency, empowers patients,27 and yields increased data. However, it is not necessarily easy and serious pitfalls can arise if it is conducted improperly. The following four substeps, summarized in Table 3-2, usually are performed in the order given. It generally takes no more than 1–2 minutes, but can take longer if the patient has many concerns.

|

Setting limits is difficult for many clinicians, so do not be surprised if this substep feels uncomfortable at first. Begin by indicating how much time is available for the interaction. This orients the patient by letting her/him know whether s/he has 10 minutes or 60 minutes and helps her/him gauge what and how much to say.28 One common pitfall is to use the word “only,” as in “We only have 20 minutes today,” which has a negative connotation. Rather say, “We’ve got about 20 minutes together today.” Some clinicians find it easier to use phrases like “short,” “medium,” or “long” to alert the patient about the amount of time you have scheduled for the visit. There will be occasional times when you have to make exceptions and extend the visit, for example, if a patient has gotten bad news and is having difficulty coming to grips with its impact, or where you may be concerned about a patient’s physical or emotional safety.

Tell the patient what you need to do during the interview to make sure the patient is properly cared for. For example, with a new patient, you may need to ask many routine questions or perform a physical examination; with a returning patient, you may need to discuss the results of a recent cholesterol test.

Most importantly, you must obtain a list of all issues your patient wants to discuss to ensure that the most important concerns are addressed during the encounter and to minimize the chance of an important concern being raised at the end of the conversation when time has run out.28,29 This substep is usually combined with the first two substeps in one sentence, for example, “We’ve got about 40 minutes together today and I need to ask a lot of questions and do an examination but let’s start by making a list of all the things you want to discuss.” Notice the use of the words “we” and “together” that help to establish a partnership with the patient.

You may need to help the patient enumerate all problems. Possible patient agenda items include, but are not limited to symptoms, requests (prescription for a sleeping pill), expectations (get sick leave), and understanding about the purpose of the interaction (perform an exercise stress test). Obtaining a complete list may require some persistence.24 Often, the patient will try to give details of the first problem. When that happens, you must respectfully interrupt and refocus the patient on setting the agenda. This can be difficult to do. It helps to hold up your fingers prominently, using them to count the problems identified. For example, while holding up one finger to signify the first problem given, you might say “Sorry to interrupt, that’s important and we’ll get back to the leg pain in a moment, but first I need to know if there is a second problem you’d like to talk about. I want to be certain we get a list of all your concerns.” You may have to do this several times, asking questions like, “Is there something else?,”30 “What else?,” “How did you hope I could help?,” or “What would a good result from this visit today look like?” In the outpatient setting it is unusual for patients to have just one concern;29,31 one study found that diabetic patients had on average three concerns they wanted to share with their clinician, the third being the most important from their perspective. Importantly, 70% of these patients never got to share their most important concern.32

Only if the patient raises a highly charged emotional issue while setting the agenda should you postpone agenda-setting and encourage further discussion at that point (eg, if the patient is acutely distraught about a recent death in the family or a recent diagnosis of cancer in himself). In most situations, however, you can set the agenda and briefly delay addressing the emotional issue. Careful agenda-setting prevents patients’ common complaint that they didn’t get to talk about all their concerns, as well as the common clinician complaint that the patient voiced her or his most serious concern at the end of the appointment.28

This substep allows you to prioritize the list and, if it is too long for the time available, to empower the patient to decide what will be addressed and what will be deferred to the next visit: “You mentioned eight concerns you wanted to cover. I don’t think we’ll have time to address them all in the time we have together today. Please choose the one or two that are most troublesome to you today, and we’ll focus on those together. I’ll see you back soon to work on the others.” Of course, if one of the items is medically concerning (eg, blood in the stool), you need to address it even if it would not be chosen by the patient.

Note how mentioning the time available at the beginning of Step 2 allows you to refer back to it without it being off-putting to the patient. You and the patient are aligned against the allotted time, instead of you and the time being aligned against the patient.

Usually, however, it is possible to cover all the patient’s concerns, in which case these are simply summarized. This also is a good point to determine, if not already known, which concern is most important. This identifies the chief concern (“chief concern” is preferred over “chief complaint” because “complaint” has a pejorative connotation).

We now begin to follow Mrs. Joanne Jones through her initial visit by providing a continuous transcript for each step; some areas are shortened later as noted for space considerations.

Clinician: | (Enters examining room and shakes hands). Ms. Joanne Jones? Welcome to the clinic. I’m Michael White, the medical student who will be working with you along with Dr. Black. How would you like me to address you? [Student uses his and her full names, welcomes the patient, and identifies his role in her care.] |

Patient: | Mrs. Jones is fine. |

Clinician: | Okay Mrs. Jones, I’ll be getting much of the information about you and will be in close contact with you about our findings and your subsequent care. |

Patient: | I wasn’t sure who I was going to see. This is my first time here. |

Clinician: | If it’s OK with you, I’ll close this door so we can hear each other better and have some privacy. [The student now ensures readiness for the interview and establishes as much privacy as possible.] |

Patient: | Sure, that’s fine. |

Clinician: | Anything I can help with before we get started? |

Patient: | Well, they didn’t give my registration card back to me. I don’t want to lose it. |

Clinician: | We’ll give that back when we’re finished today. They always keep them. Is there something else? |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Would you like to sit in that chair? It’s more comfortable than the examining table. [The student has addressed this barrier to communication, establishes equal eye level, ensures comfort and puts the patient at ease.] |

Patient: | Sure. Thanks. (She moves.) |

Clinician: | Well, I’m glad to see you made it despite the snow. I thought spring was here last week. |

Patient: | I guess not. My kids have been home the last 2 days. I’m ready to get them back to school! I’m getting spoiled with them both in school. |

Clinician: | People have had all kinds of trouble getting in here for their appointments since the snow. It’s no fun. |

Patient: | You’re telling me. I don’t even ski! [The student has set the stage, a light conversation has occurred, and the patient is joking.] |

Clinician: | (laughs) Well, we’ve got about 40 minutes today and I know I’ve got a lot of questions to ask and that we need to do a physical exam. Before we get started, though, I like to get a list of the things you wanted to address today. You know, so we’re sure everything gets covered. [Student gives his agenda in one statement. Doing this first models the more difficult task to follow: obtaining the patient’s agenda] |

Patient: | It’s these headaches. They start behind my eye and then I get sick to my stomach so I can’t even work. My boss is really getting upset with me. He thinks that I don’t have anything wrong with me and says he’s going to report me. Well, he’s not really my boss, but rather is … (student interrupts) |

Clinician: | That sounds difficult and really important. Before we get into the details, though, I’d like to find out if there are some other problems you’d like to look at today, so we can be certain to cover everything you want to. We’ll get back to the headache and your boss after that. Your headache and your boss—that’s two things (holding up two fingers). Is there something else you wanted to address today? |

Patient: | Well, I wanted to find out about this cold that doesn’t seem to go away. I’ve been coughing for 3 weeks. |

Clinician: | (Holding up three fingers now): OK, cough; what other concerns do you have? |

Patient: | Well, I did want to find out if I need any medicine for my colitis. That’s doing ok now but I’ve had real trouble in the past. It started bothering me back in 1999 and I’ve had trouble off and on. I used to take cortisone and … (student interrupts); [Notice that the student has now interrupted the patient twice in order to complete the list of concerns. This is necessary, done respectfully, to complete the agenda in a timely way.] |

Clinician: | (Holding up five fingers): So, there are two more problems we can look into, the colitis and the medications. We’ll get back to all these soon; they’re all important. To make sure we get all your questions covered, though, is there something else? |

Patient: | No. The headache is the main thing. |

Clinician: | So, we want to cover the headaches and the problem they cause at work, cough, colitis, and the medications for the colitis. Is that right? [It is here that the patient and student would negotiate what to cover at this visit if the student determined that the patient had raised too many issues to cover on this day.] |

Patient: | That’s about it. |

Clinician: | And do I understand correctly that the headache is the worst problem? [Mrs. Jones’ headache is her most bothersome concern, what we earlier defined as the chief concern.] |

Patient: | Yes. |

Opening the History of Present Illness (Step 3)

Having set the stage (Step 1) and obtained the agenda (Step 2), we now use the patient-centered skills learned in the last chapter to begin to elicit the history of the present illness (HPI). As reviewed in Chapter 1, the HPI is the most important component of the interview because it reflects the patient’s current problem in its psychosocial and biomedical totality. The HPI begins at the beginning of the interview (patient-centered part) and continues into the middle of the interview (clinician-centered part), where relevant details are clarified using clinician-centered interviewing skills.

Step 3, summarized in Table 3-3, consists of asking one open-ended question (or making one open-ended request) and then allowing the patient to talk. It establishes an easy flow of talk from the patient, conveys that the clinician is attentively listening, and gives a feel for “what the patient is like.” Ordinarily, Step 3 lasts no more than 30–60 seconds as the interviewer listens attentively, using the following substeps.

|

When first learning the medical interview, some students are so nervous or preoccupied with what they should say next that they miss important information from the patient’s opening statement. Step 3 gives you the opportunity to take a deep breath, relax and listen to the patient. It starts with an open-ended beginning request or question, for example, “So headaches are the big problem, tell me more.” Avoid saying, “Tell me a little bit about the headache,” because you do not want to hear a little bit about the symptom, you want to encourage a chronological narrative. Sometimes, especially with reticent or disorganized patients, it is helpful to be clear about your desire: “Tell me all about the headache, starting at the beginning and bringing me up to now.” Sometimes an open-ended beginning question is not necessary; having completed the agenda, especially if there is only one or a few related items, many patients continue spontaneously.

Following the open-ended beginning question, allow the patient to talk freely for 30–60 seconds or so to get the gist of her or his primary concern. Encourage a continued free flow of information using the nonfocusing open-ended skills described in Chapter 2. Silence, nonverbal gestures (eye contact, attentive behavior, hand gestures), and neutral utterances (Uh-huh, Mmm) encourage the patient to continue speaking. Listen carefully to the patient’s opening statement for clues to the patient’s story. Continue to use nonfocusing open-ended skills for as long as the patient is giving you information that helps you learn about the patient’s symptom story or its personal or emotional context.

Many clinicians are reluctant to use nonfocusing skills in the beginning of the interview because of fears that patients will go on incessantly, and that nothing will get accomplished. Research shows that when patients are given all the time they need to complete their initial statement, in nearly 80% of the cases it lasts 2 minutes or less; in the minority of instances where it went longer, physicians agreed that the patients used that time well.33

Although uncommon, patients sometimes do not talk freely. If this occurs, and five seconds or so of silence does not lead the patient to resume talking, you can use the focusing open-ended skills (echoing, request, summary) to promote a free flow of information. If focusing open-ended skills are not effective, you can also use closed-ended questions about the patient’s problem to get a dialogue going.

Although you are verbally quiet during the brief Step 3, you should be very mentally active, thinking about what the information means. Observe the patient for nonverbal cues, reviewed in Chapter 7; for example, depressed facial expressions, arms folded across the chest, toes tapping nervously. Observe also for clues in the following areas that will give additional information about the patient:34,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree