17 The anorectum

Applied surgical anatomy

Anal musculature and innervation

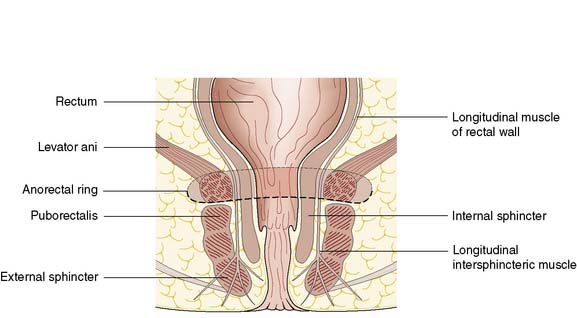

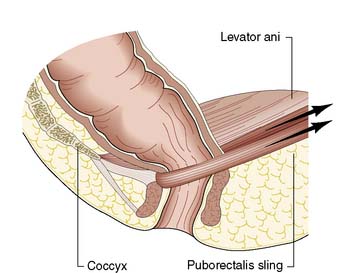

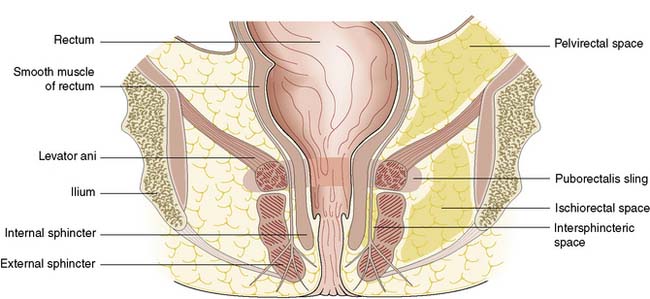

The anal canal is 3–4 cm long in males and slightly shorter in females. It consists of two concentric muscle layers known as the internal and external sphincters (Fig. 17.1). The internal sphincter is a condensation of the circular smooth muscle of the rectum and is a continuation of the circular muscle of the gastrointestinal tract. It is controlled by the autonomic nervous system with fibres from the pelvic sympathetic nerves, the lower lumbar ganglia and the pre-aortic/inferior mesenteric plexus. Parasympathetic fibres arise from the sacral plexus. The smooth muscle of the internal sphincter maintains tone and contributes to resting pressure within the anal canal, so playing an important role in maintaining continence. The longitudinal muscle of the gut ends at the anus as a series of fibrous bands that radiate to the perianal skin, and is of little consequence to perianal disease. The striated muscle of the external sphincter is under voluntary control, being innervated bilaterally by the internal pudendal nerves and the fourth branch of the sacral plexus. The circular muscle tube of the external sphincter blends with the lower part of the levator ani, known as the puborectalis sling (Fig. 17.2). The puborectalis fibres of the levator ani originate from the posterior aspect of the pubic symphysis and pass posteriorly to join the external sphincter. The levator ani muscles themselves are also important in maintaining the relationship of the anus and rectum during defaecation.

Anal canal epithelium

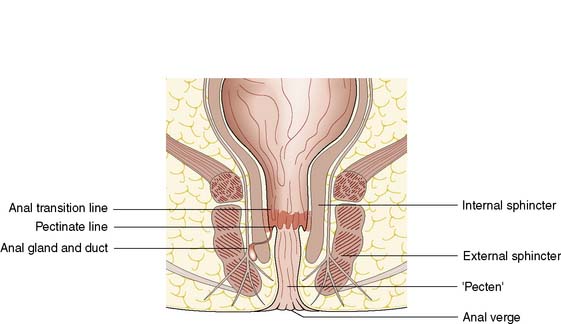

The cell type of the anal canal epithelium determines why certain diseases, such as tumours and viral infections, affect only particular levels of the canal. The epithelium of the anal canal is specialized and contains three distinct zones. The external zone (from dentate line to anal verge) is keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium. There is a short, modified, anal transitional zone of non-keratinized squamous epithelium, which lies immediately proximal to the dentate line, separated from the columnar epithelial of the anal canal but continuous with the rectal epithelium. The anal valves are crescentic mucosal folds that form a serrated or dentate line on the luminal aspect of the mid-anal canal (Fig. 17.3). The dentate line represents the line of fusion between the endoderm of the embryonic hindgut and the ectoderm of the anal pit. Thus, the epithelium is innervated by the autonomic nervous system and is insensate with respect to somatic sensation. The canal lining below the dentate line is innervated by the peripheral nervous system and so conditions affecting this region, such as abscess, anal fissure or tumour, result in anal pain.

There are 4–8 specialized anal glands located within the substance of the internal sphincter or in the space between the internal and external sphincters at the level of the mid-anal canal; these glands have ducts that open directly on to the dentate line (Fig. 17.4). They are involved in the aetiology of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano. The function of the anal glands is to secrete mucus, lubricating and protecting the delicate epithelium of the anal transition zone. The ducts from these glands open into the folds of mucosa at the dentate line. The relevance of these glands lies in the fact that they are the source of most perianal abscesses. When an anal gland duct becomes occluded, the obstructed gland may become infected with gut organisms such as coliforms, and anaerobic bacteria such as Bacteroides.

Anorectal disorders

Haemorrhoids

Clinical features

• First-degree piles are those that bleed, are visible on proctoscopy but do not prolapse

• Second-degree piles are those that prolapse during defaecation but reduce spontaneously

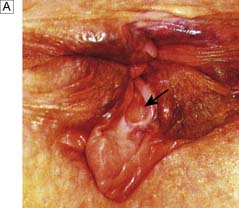

• Third-degree piles are prolapsed constantly but can be reduced manually (Fig. 17.5)

Management

Non-operative approaches

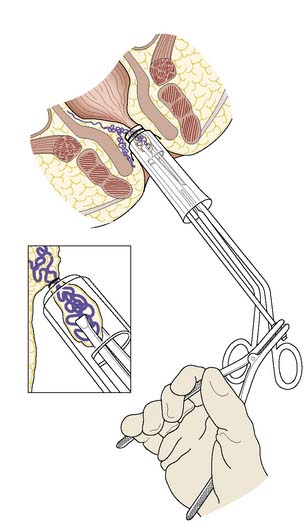

There are many non-operative approaches to the treatment of haemorrhoids, the aim of which is to cause fibrosis and shrinkage of the protruding haemorrhoidal cushion in order to prevent bleeding and prolapse. Current outpatient clinic treatment approaches include application of small rubber bands to strangulate the pile (using a special Barron’s bander); submucosal injection of sclerosant; and the application of heat by infrared photocoagulation. There is no strong evidence that any of these approaches is much better than doing nothing at all. In the long term, the symptoms of untreated piles tend to wax and wane, and the recurrence of symptoms after any of these procedures is much the same as without any treatment. However, of all the non-operative treatments, rubber band ligation (Fig. 17.6) may be the most effective in the short term. Where there is a significant cutaneous component to the piles, any of the outpatient treatments is likely to be painful because of the cutaneous nerve supply, and is also unlikely to succeed. In these circumstances, the decision should be to do nothing but reassure the patient, or to offer an operation.

Operative approaches

The principle of haemorrhoidectomy involves total removal of the haemorrhoidal mass and securing of haemostasis of the feeding vessel. The wound can be left open or can be closed, but there are rarely problems with healing or infection. In some cases, there are secondary haemorrhoids between the main right anterior, right posterior and left lateral positions, and these are also removed as part of the operation. Recently, a different surgical approach using a circular stapler has been developed, the stapled anopexy. This technique aims to divide the mucosa and haemorrhoidal cushions above the dentate line in order to transect the feeding vessels and hitch up the stretched supporting fibroelastic tissue, rather than removing the whole haemorrhoidal mass as in the standard haemorrhoidectomy. Stapled haemorrhoidectomy may have a place for the treatment of symptomatic first- and second-degree piles (EBM 17.1). With all surgical approaches to treating

17.1 Haemorrhoids

Summary Box 17.3 Haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoids are common and best treated conservatively.

• First-degree: visible in the lumen on proctoscopy but do not prolapse

• Second-degree: prolapse on defaecation but return spontaneously

• Third-degree: remain prolapsed but can be replaced digitally

• Fourth-degree: long-standing prolapse and cannot be replaced in the anal canal.

• First-degree: advice on avoiding constipation and straining

• Second-degree: conservative management, banding, injection sclerotherapy, haemorrhoidectomy

• Third-degree: if symptomatic, haemorrhoidectomy

• Fourth-degree: thrombosed piles are usually treated conservatively in the first instance; interval haemorrhoidectomy may not be required.

piles, it is important to consider that the haemorrhoidal cushions contribute to fine control of continence. Hence, an element of anal incontinence can be one of the long-term sequelae of any haemorrhoidectomy. Surgery should not be considered lightly.

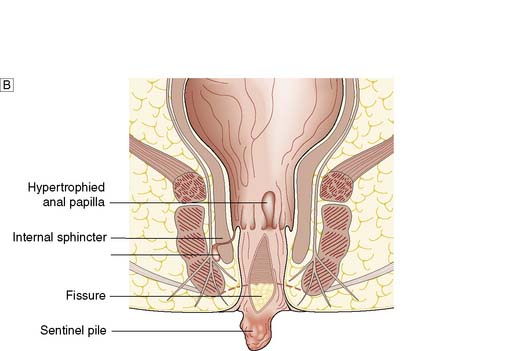

Fissure-in-ano

Fissure-in-ano is a common condition characterized by a linear anal ulcer, often with the internal sphincter visible in the base, affecting the anal canal below the dentate line from the anal transition zone to the anal verge (Fig. 17.7). There is often little in the way of granulation tissue in the ulcer base. Owing to failed attempts at healing, there may be a tag of skin at the lowermost extent of the fissure, known as a ‘sentinel pile’. At the proximal extent of the fissure there may be a hypertrophied anal papilla. Sometimes fissures will heal incompletely and mucosa will bridge the edges of the fissure. This results in a low perianal fistula and may present years later. Fissures are most frequently observed in the posterior midline of the anal canal, although anterior fissures may occur in women following childbirth; they are rarely seen in males.

Clinical features and diagnosis

The diagnosis should be suspected from the history alone and is confirmed by gently parting the superficial part of the anal sphincter with the gloved fingers to reveal the characteristic linear ulcer. There may be an associated ‘sentinel pile’, which consists of heaped-up skin at the lowermost extent of the linear ulcer (Fig. 17.7). It is often too painful to perform a digital rectal examination or a proctoscopy, and so this is best left until after treatment is instigated. However, it is important to complete clinical assessment with rigid sigmoidoscopy at a later date. A full history is important to exclude previous perianal surgery, perianal abscess, trauma during childbirth or symptoms consistent with Crohn’s disease.

Management

Until the relatively recent advent of chemical sphincterotomy as first-line treatment, surgery was the only option. Surgery still has a major role in the management of patients who have fissures resistant to medical treatment, or who have recurrence. Anal stretching has been abandoned, as it is associated with significant sphincter damage and the risk of incontinence (EBM 17.2). Lateral sphincterotomy is the most common operation for anal fissure and involves controlled division of the lower half of the internal sphincter at the lateral position (3 o’clock or 9 o’clock with the patient in the lithotomy position). There is a small but appreciable risk of late anal incontinence following lateral sphincterotomy. This is usually only to gas, but occasionally faecal incontinence to liquid or solid can occur, particularly in women who have had birth-related anal sphincter damage. In women, it may therefore be more appropriate to avoid further division of any sphincter muscle, and this can be achieved using an anal advancement flap or a rotation flap to cover the ulcerated base of the fissure and allow new, well-vascularized skin to heal the ulcer and reduce the associated anal spasm.