Overview

Nearly one-fifth of all workers in the industrialized world are over 50 and the number of younger workers entering the labour force each year is declining

Increasing the economic contribution of older workers could ameliorate the looming pensions deficits and promote better health

Many countries have now enacted legislation to ban age discrimination in employment

There is a degree of physical and mental decline with age, but this is highly variable and a degree of compensation can occur

Initiatives to encourage employers to engage older workers are in place in many countries; adaptation of workplaces and working practices is the key

Introduction

All industrialized nations are currently experiencing dynamic changes to both their population structures and their workforces. Already nearly one-fifth of all workers in the industrialized world are over 50. By 2030, half the UK population will be aged over 50, and one-third over 60. At the same time the ageing of the population structure will have significantly reduced the number of younger workers entering the labour force each year. This alongside growing age discrimination legislation in European countries will require employers to address the needs of retaining its older workers in suitable occupations.

Demographics and Policy Initiatives

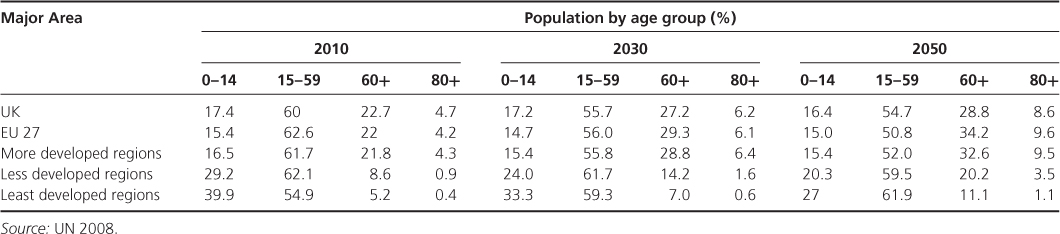

The next decade will thus see a rapid shift towards increased elderly dependency ratios in most industrialized countries. The EU-25 Elderly Dependency Ratio is set to double as the working-age population (15–64 years) decreases by 48 million between now and 2050, and the EU-25 will change from having four to only two persons of working age for each citizen aged 65 and above (European Commission, 2006). In 2010 the working age population comprised 70% of Europe’s population, with older and younger dependents equal in size, and representing a total dependency ratio of 46:100 workers. From 2010 to 2050, the total dependency will increase to 73:100 workers (Table 18.1). There is thus a widespread assumption that the structural ageing of the European population will lead to a demographic deficit, whereby the population of working age is insufficient to support the increasing proportion of older dependents.

Table 18.1 Distribution of the population of major areas by broad age groups, 2010, 2030 and 2050 (medium variant)

It is now accepted by most OECD governments that some remedial measures will be needed. These measures may be approached by altering the age composition of the population through encouraging changes in fertility and migration rates to increase the proportion of young people, and by increasing the productivity of the population by encouraging higher labour force participation rates and extending working lives by altering entry and exit ages. Increasing the economic contribution of older workers is an important measure for industrialized countries to consider. This is particularly the case in those European countries where early retirement rates are high.

Encouraging longer working lives:

- reduces pension longevity for the individual and societies

- has the potential to tackle issues emerging from the demographic deficit, through the retention of experience and skills held by older workers

- should in the longer term reduce national public health bills by increasing the wellbeing of its older population through continued usefulness and mental and physical activity in later years.

There is now general acceptance that future cohorts of older men and women, with higher levels of education, skills and training, will be able to maintain high levels of productivity given supportive and conducive working environments (Harper, 2010).

Lengthening Working Lives

Although there is a general acceptance that, faced with population ageing, longer working lives must be encouraged (OECD 2006) there are also concerns. These include:

- the relationship of life expectancy to healthy life expectancy

- the changing physical and mental capacity of individuals as they age

- the need to adapt working practices and environments for older workers

- the need to provide specialist training for older workers.

The Relationship of Life Expectancy to Healthy Life Expectancy

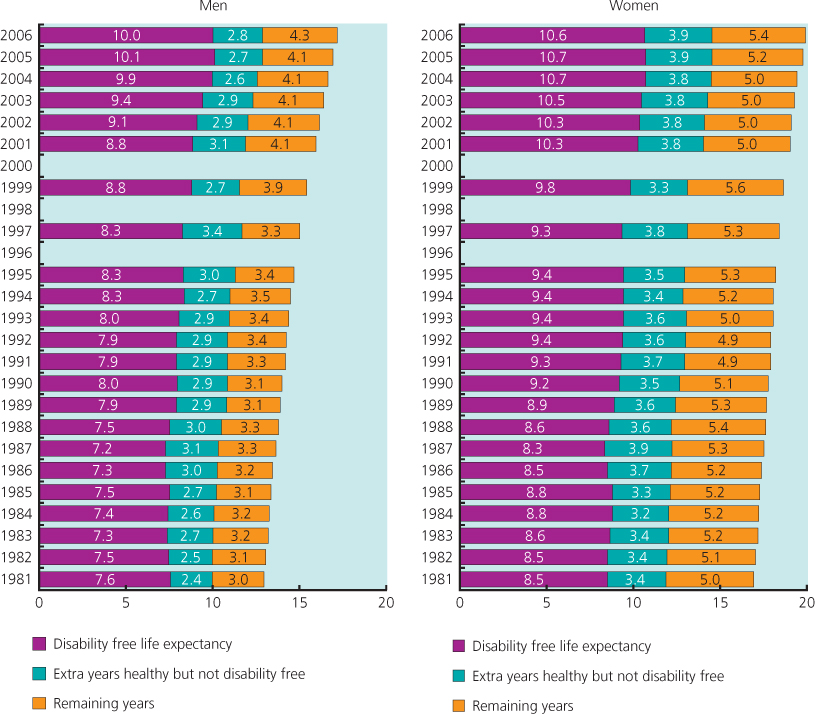

There is considerable debate over whether healthy or disability-free life expectancy has kept pace with life expectancy. Whereas some predictions for Europe and the United States forecast that both men and women in their early 70s can expect to live well into their 80s, enjoying most of those years disability free (Manton et al. 2006), historical data for the UK suggests that for both men and women the increases in ‘healthy life expectancy’ (HLE), and ‘disability-free life expectancy’ (DFLE) in particular, have not kept pace with total gains in life expectancy. This is important, as both of these measures provide an indication of the length of time an individual remains ‘healthy’ and are thus more closely aligned with an individual’s ability to work later in life, and in turn the ability to defer reliance on the state pension to an older age (Figure 18.1 and Table 18.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree