INTRODUCTION

An “acute abdomen” denotes any sudden, spontaneous, nontraumatic, severe abdominal pain, typically of less than 24 hours duration. The acute abdomen requires rapid and specific diagnosis as several etiologies demand urgent operative intervention. Because there is frequently a progressive underlying intra-abdominal disorder, undue delay in diagnosis and treatment may adversely affect outcome.

The approach to a patient with an acute abdomen must be orderly and thorough. An acute abdomen should be suspected even in a patient with only mild or atypical presentations. Increasingly, certain patient populations present with atypical complaints, including the immunocompromised, elderly and gastric bypass patients. The history and physical examination often suggest the probable cause, allow formation of a differential diagnosis, and guide the choice of initial diagnostic studies. The clinician must then decide if in-hospital observation is warranted, if additional tests are needed, if early operation is indicated, or if nonoperative treatment would be more suitable.

All clinicians should be familiar with the presenting pattern of the most common causes of an acute abdomen (Table 21–1) and their atypical presentations in certain patient populations. Moreover, they should be familiar with regional specific disease patterns. While the most common cause of abdominal pain in patients presenting to the emergency department is nonspecific discomfort, missing treatable causes of abdominal pain can be disastrous for the patient.

Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders

Liver, Spleen, and Biliary Tract Disorders

Pancreatic Disorders

Urinary Tract Disorders

Gynecologic Disorders

Vascular Disorders

Peritoneal Disorders

Retroperitoneal Disorders

|

HISTORY

History taking by an experienced physician is key to focusing the evaluation of a patient with an acute abdomen. Taking a patient history is an active process whereby a large number of diagnostic possibilities are considered in order to systematically eliminate less likely conditions.

Pain is the most common and predominant presenting feature of an acute abdomen. Careful consideration of the location, severity, mode of onset and progression, and the character of the pain will suggest a preliminary list of diagnoses.

The location of pain serves only as a rough guide to the diagnosis; “typical” descriptions are reported in only two-thirds of cases. This variability is due to atypical pain patterns, a shift of maximum intensity away from the primary site, or advanced or severe disease. In patients presenting with diffuse peritonitis, generalized pain may completely obscure the precipitating event. Fortunately, some general patterns do emerge that provide clues to diagnosis and narrow the differential of the acute abdomen. Pain confined to either upper quadrant may be evaluated by anatomic consideration of acute conditions affecting underlying organs.

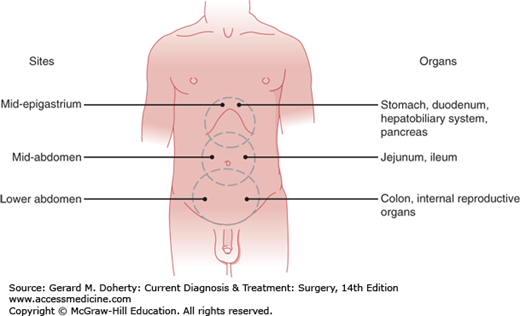

Because of the complex dual visceral and parietal sensory networks innervating the abdominal area, pain is not as precisely localized in the abdomen as in the extremities. Visceral sensation is mediated primarily by afferent C fibers located in the walls of hollow viscera and in the capsules of solid organs. Unlike cutaneous pain, visceral pain is elicited by distention, inflammation or ischemia stimulating the receptor neurons, or by direct involvement (eg, malignant infiltration) of sensory nerves. Visceral pain is a centrally perceived sensation, generally slow in onset, dull, poorly localized and protracted. The pain may be due to increased wall tension or luminal distention or forceful smooth muscle contraction (colic) producing diffuse, deep-seated pain. Visceral pain is most often felt in the midline because of the bilateral sensory supply to the spinal cord. Because different visceral structures are associated with different sensory levels in the spine (Table 21–2), visceral pain may be felt in the midepigastrium, periumbilical area, lower abdomen, or flank areas (Figure 21–1) depending on the organ involved.

| Structures | Nervous System Pathways | Sensory Level |

|---|---|---|

| Liver, spleen and central part of diaphragm | Phrenic nerve | C3-5 |

| Peripheral diaphragm, stomach, pancreas, gallbladder and small bowel | Celiac plexus and greater splanchnic nerve | T6-9 |

| Appendix, colon and pelvic viscera | Mesenteric plexus and lesser splanchnic nerve | T10-11 |

| Sigmoid colon, rectum, kidney, ureters and testes | Lowest splanchnic nerve | T11-L1 |

| Bladder and rectosigmoid | Hypogastric plexus | S2-4 |

In contrast, parietal pain is mediated by both C and A delta nerve fibers, the latter being responsible for the transmission of more acute, sharper, better localized pain sensation. Direct irritation of the somatically innervated parietal peritoneum by pus, bile, urine, or gastrointestinal secretions leads to a more precisely localized pain. Parietal pain is more easily localized than visceral pain because the somatic afferent fibers are directed to only one side of the nervous system. The cutaneous distribution of parietal pain corresponds to the T6-L1 areas. Abdominal parietal pain is conventionally described as occurring in one of the four abdominal quadrants or in the epigastric or central abdominal area.

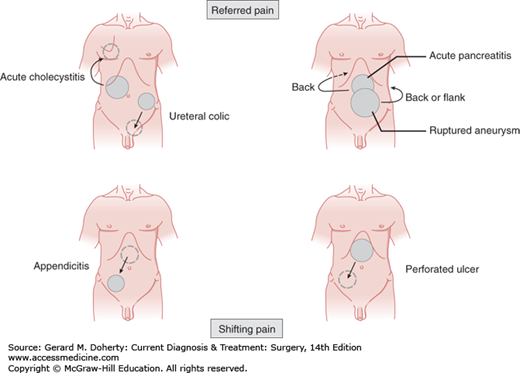

Abdominal pain may be referred or may shift to sites removed from the primarily affected organs (Figure 21–2). Referred pain denotes noxious (usually cutaneous) sensations perceived at a site distant from that of a strong primary stimulus. Distorted central perception of the site of pain is due to the confluence of afferent nerve fibers from disparate areas within the posterior horn of the spinal cord. For example, pain due to subdiaphragmatic irritation by air, peritoneal fluid, blood, or a mass lesion is referred to the shoulder via the C4-mediated (phrenic) nerve. Pain may also be referred to the shoulder from supradiaphragmatic lesions such as pleurisy or lower lobe pneumonia. Although more often perceived in the right scapular region, referred biliary pain may mimic angina pectoris if it is perceived in the anterior chest or left shoulder areas.

Spreading or shifting pain parallels the course of the underlying condition. The site of pain at onset should be distinguished from the site at presentation. The chronology of a patient’s pain may be as important as the location itself. Beginning classically in the epigastric or periumbilical region, the initial visceral pain of acute appendicitis shifts to become sharper parietal pain localized in the right lower quadrant when the overlying peritoneum becomes directly inflamed (Figure 21–2). With a perforated peptic ulcer, pain almost always begins in the epigastrium, but as leaked gastric contents track down the right paracolic gutter, pain may descend to the right lower quadrant.

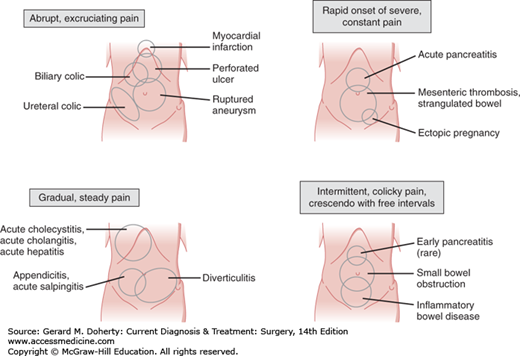

The mode of onset of pain reflects the nature and severity of the underlying process. Onset may be explosive (within seconds), rapidly progressive (within 1-2 hours), or gradual (over several hours). Unheralded, excruciating generalized pain suggests an intra-abdominal catastrophe such as a perforated viscus or rupture of an aneurysm, ectopic pregnancy, or abscess. Accompanying systemic signs (tachycardia, sweating, tachypnea, shock) soon supersede the abdominal disturbances and underscore the need for rapid resuscitation and laparotomy.

A less dramatic clinical picture is steady, mild pain becoming intensely centered in a well-defined area within 1-2 hours. Any of the above conditions may present in this manner, but this is more typical of acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, strangulated bowel, mesenteric infarction, renal or ureteral colic and proximal small bowel obstruction.

Finally, some patients initially have slight—at times only vague—abdominal discomfort that is fleetingly present diffusely throughout the abdomen. It may be unclear whether these patients even have an acute abdomen or whether the illness is likely to be a matter for medical rather than surgical attention. Associated gastrointestinal symptoms are infrequent at first, and systemic symptoms are absent. Eventually, the pain and abdominal findings become more pronounced, steady and are localized to a smaller area. This gradual onset pattern leading to a more localized pain may reflect a slowly developing condition or the body’s defensive efforts to cordon off an acute process. This broad category includes acute appendicitis (especially with the appendix in a retrocecal position), incarcerated hernias, distal small bowel and large bowel obstructions, uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease, walled-off (often malignant) visceral perforations, some genitourinary and gynecologic conditions, and milder forms of the rapid-onset group mentioned in the first paragraph.

The nature, severity and periodicity of pain provide useful clues to the underlying pathology (Figure 21–3). Pain may be continual or intermittent. Steady pain is more common and often indicates a process that will lead to peritoneal inflammation. It may be constant in severity or fluctuate, but it is always present. Sharp superficial constant pain due to peritoneal irritation is typical of perforated ulcer or a ruptured appendix, ovarian cyst, or ectopic pregnancy. Intermittent, crampy pain (colic) may occur for short or long periods but is punctuated by pain free intervals and is most characteristic of obstruction of a hollow viscus. The gripping, mounting pain of small bowel obstruction (and occasionally early pancreatitis) is usually intermittent, vague, deep-seated and crescendo at first but becomes sharper, unremitting and better localized. Unlike the disquieting but bearable pain associated with bowel obstruction, pain caused by lesions occluding smaller conduits (bile ducts, uterine tubes, ureters) rapidly becomes unbearably intense. The pain-free intervals reflect intermittent smooth muscle contractions. In the strict sense, the term “biliary colic” is a misnomer because biliary pain does not remit as bile ducts do not have peristaltic movements.

The quality of a patient’s pain leads to the use of certain descriptors to describe different types of pain and may be typical of certain pathologies. The “aching discomfort” of ulcer pain, the “stabbing, breathtaking” pain of acute pancreatitis and mesenteric infarction, the “gripping” pain of a bowel obstruction and the “tearing” pain of ruptured aortic aneurysm remain apt descriptions. Despite the use of such descriptive terms, the quality of visceral pain is not a reliable clue to its cause.

The intensity of a patient’s pain may relate to the severity of the insult. Agonizing pain denotes serious or advanced disease. Colicky pain is usually promptly alleviated by analgesics. Ischemic pain due to strangulated bowel or mesenteric thrombosis is only slightly assuaged even by narcotics. Nonspecific abdominal pain is usually mild, but mild pain may also be found with perforated ulcers that have become localized and in mild acute pancreatitis. An occasional patient will deny pain but complain of a vague feeling of abdominal fullness that feels as though it might be relieved by a bowel movement. This visceral sensation (gas stoppage sign) is due to reflex ileus induced by an inflammatory lesion walled off from the free peritoneal cavity, as in retrocecal appendicitis.

Past episodes of pain and factors that aggravate or relieve pain should be noted. Pain caused by localized peritonitis, especially when it affects upper abdominal organs, tends to be exacerbated by movement or deep breathing.

The location, character and severity of the pain in relation to its duration of onset and presence of systemic symptoms help to differentiate rapidly progressive surgical conditions (eg, intestinal ischemia) from more indolent or medical causes (eg, ruptured ovarian cyst) and allows formation of a differential diagnosis.

Anorexia, fever, nausea and vomiting, constipation/obstipation, or diarrhea, often accompany abdominal pain, but are nonspecific symptoms and have limited diagnostic value.

When sufficiently stimulated by secondary visceral afferent fibers, the medullary vomiting centers activate efferent fibers to induce reflex vomiting. Hence, pain in the acute surgical abdomen usually precedes vomiting, whereas the reverse holds true in medical conditions. Vomiting is a prominent symptom in upper gastrointestinal diseases such as Boerhaave syndrome, Mallory–Weiss syndrome, acute gastritis and acute pancreatitis. Severe, uncontrollable retching provides temporary pain relief in moderate attacks of pancreatitis. The absence of bile in the vomitus is a feature of pyloric stenosis or gastric outlet obstruction. Where associated findings suggest bowel obstruction, the onset and character of vomiting may indicate the level of the lesion. Recurrent vomiting of bile-stained fluid is typical of proximal small bowel obstruction. In distal small or large bowel obstruction, prolonged nausea precedes vomiting, which may become feculent in late cases. Although vomiting may present in either acute appendicitis or nonspecific abdominal pain, coexisting nausea and anorexia are more suggestive of the former condition.

Reflex ileus is often induced by visceral afferent fibers stimulating efferent fibers of the sympathetic autonomic nervous system (splanchnic nerves) to reduce intestinal peristalsis. Hence, paralytic ileus undermines the value of constipation in the differential diagnosis of an acute abdomen. Constipation itself is hardly an absolute indicator of intestinal obstruction. However, obstipation (the absence of passage of both stool and flatus) strongly suggests mechanical bowel obstruction if there is progressive painful abdominal distention or repeated vomiting.

Copious watery diarrhea is characteristic of gastroenteritis and other medical causes of an acute abdomen. Blood-stained diarrhea suggests ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, or bacillary or amebic dysentery. It is also found with ischemic colitis but often absent in intestinal infarction due to superior mesenteric artery occlusion.

Fever is a marker of inflammation and may be present in a variety of surgical conditions in the abdomen if they are allowed to progress. The sensitivity of this finding is low as the ability of many patient populations to mount a fever is compromised and for most diseases leading to acute abdomen fever is low grade or absent.

These are extremely helpful if present. Significant weight loss may suggest cancer or more chronic mesenteric ischemia. Jaundice suggests hepatobiliary disorders. Hematochezia or hematemesis may suggest a gastroduodenal lesion or Mallory–Weiss syndrome; melena a lower GI bleed or colonic ischemia and hematuria, ureteral colic, or cystitis. The passage of blood clots or necrotic mucosal debris may be the sole evidence of advanced intestinal ischemia.

A complete past medical history is crucial to identify both medical conditions related to the presentation of the acute abdomen as well as conditions of associated pulmonary, renal and cardiac systems that may mimic the acute abdomen in their presentation. Many chronic medical conditions complicate the patient’s presentation and increase their surgical risk. An assessment of the patient’s cardiovascular and pulmonary status should always be done before proceeding to the operating room. Liver disease should be noted as it increases risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, and in severe disease may be complicated by ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. In patients with vascular disease or atrial fibrillation mesenteric ischemia should be included in the differential. Inflammatory bowel disease can cause severe abdominal pain often treated medically but may be complicated by processes requiring more emergent intervention including intra-abdominal abscess, stricture, obstruction, or perforation.

A patient should also be asked about any history of recent trauma. Delayed splenic bleeding is one of the more common examples of traumatic injuries presenting in delayed fashion.

Any history of a previous abdominal, groin, vascular, or thoracic operation may be relevant to the current illness. Particular attention to the mode of operation (laparoscopic, open, endovascular) and any anatomic reconstructions may clarify aspects of the current complaint. If possible within the time constraints imposed by the urgency of the current problem, operative notes and pathology reports should be obtained and reviewed.