11 The abdominal wall and hernia

Umbilicus

Developmental abnormalities

Persistent vitello-intestinal duct

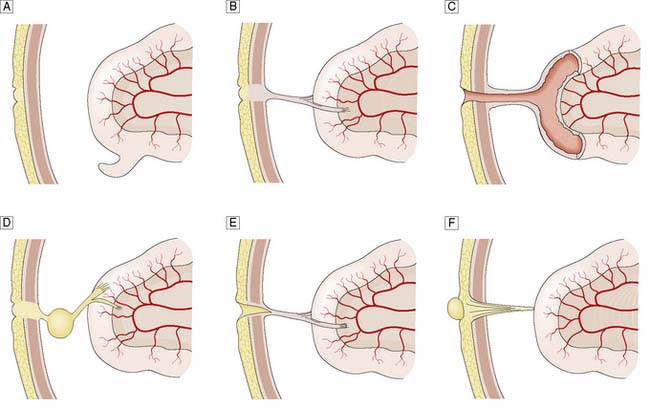

The vitello-intestinal duct runs in intrauterine life from the apex of the midgut loop to the yolk sac. It is normally obliterated long before birth, but part of it may persist as a Meckel’s diverticulum on the antimesenteric border of the ileum. Rarer abnormalities include persistence of a band attaching the umbilicus to a Meckel’s diverticulum or a loop of ileum; a patent communication (fistula) between the ileum and umbilicus; an encysted portion of the duct that does not connect with the ileum (enterocystoma); an umbilical sinus; and a persistent umbilical portion of the duct, which forms a polypoidal raspberry-like tumour of the umbilicus (enteroteratoma) (Fig. 11.1). Symptomatic remnants may have to be excised, although a broad-based Meckel’s diverticulum is usually left alone if found incidentally at laparotomy. Persisting bands can cause intestinal obstruction.

Abdominal hernia

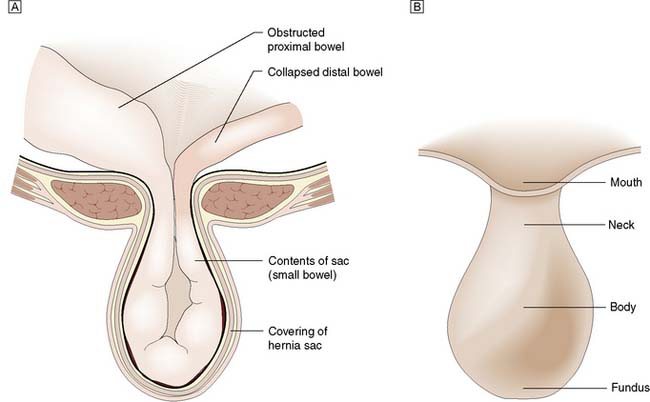

A hernia is an abnormal protrusion of a cavity’s contents, through a weakness in the wall of the cavity, taking with it all the linings of the cavity, although these may be markedly attenuated (Fig. 11.2). Hernias of the abdominal wall are common. Multiple factors contribute to the development of hernias. In essence, hernias can be considered design faults, either anatomical or through inherited collagen disorders, although these two factors work together in the majority of patients. Hernias may exploit natural openings such as the inguinal and femoral canals, umbilicus, obturator canal or oesophageal hiatus, or protrude through areas weakened by stretching (e.g. epigastric hernia) or surgical incision. In addition to these ‘weak’ anatomical areas, the collagen make up of the tissues, especially the Type I to III collagen ratio is also important. Type I imparts the strength to the tendon or fascia, Type III provides elastic recoil to the tissue. The Type I/III collagen ratio varies between individuals but is constant in all the fascia of a particular individual. Hernias can be considered as a disease of collagen metabolism.

The hernia is immediately invested by a peritoneal sac drawn from the lining of the abdominal wall (Fig. 11.2). The sac is covered in turn by those tissues that are stretched in front of it as the hernia enlarges (i.e. the coverings). The neck of the sac is the constriction formed by the orifice in the abdominal wall through which the hernia passes. A hernia may contain any intra-abdominal structure but most commonly contains omentum and/or small bowel. A hernia may involve only part of the circumference of the bowel (Richter’s hernia), a Meckel’s diverticulum (Littré’s hernia) or an incarcerated appendix (Amyand’s hernia). A sliding inguinal hernia is defined as one in which a viscus forms a portion of the wall of the hernia sac. Most commonly, the viscus involved is caecum, sigmoid colon or urinary bladder. In the early stages of a hernia, sometimes the hernial contents are pre-peritoneal fat only, such as a lipoma of the cord which can mimic an inguinal hernia.

Summary Box 11.1 Hernia

• A hernia is an abnormal protrusion of a cavity’s contents through a weakness in the wall of the cavity, but takes with it all the linings of the cavity

• Hernias of the abdominal wall are common and may exploit natural openings or weak areas caused by stretching or surgical incisions in association with a defect in collagen metabolism

• Abdominal hernias have a peritoneal sac, the neck of which is often unyielding and constitutes a potential source of compression of the hernial contents

• Hernia may be classified as reducible or irreducible, and the contents (e.g. bowel) may become obstructed or strangulated

• Strangulation denotes compromise of the blood supply of the contents and its development significantly increases morbidity and mortality. The low-pressure venous drainage is occluded first and then the arterial supply becomes occluded, with the development of gangrene.

Inguinal hernia

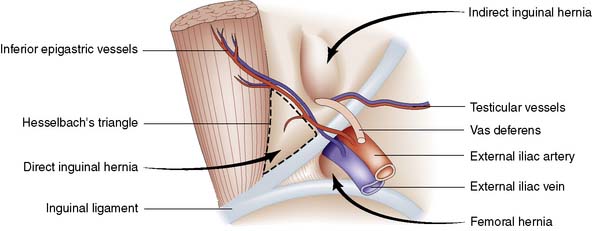

Groin hernias account for three-quarters of all abdominal wall hernias, and inguinal herniorrhaphy is one of the most frequently performed general surgical procedures. The most common types of groin hernia are indirect inguinal (60%), direct inguinal (25%) and femoral (15%) (Fig. 11.3). Most (85%) groin hernias occur in males. Inguinal hernias occur in 1–3% of all newborn males. The incidence in premature infants is 30 times that seen at term. In early life, an indirect inguinal hernia is by far the most common variety. After middle age, weakness of the abdominal musculature leads to an increasing incidence of direct inguinal hernias. Femoral hernias are relatively more common in females (possibly because of stretching of ligaments and widening of the femoral ring in pregnancy), but an indirect inguinal hernia is still the most common type of groin hernia in women.

Surgical anatomy

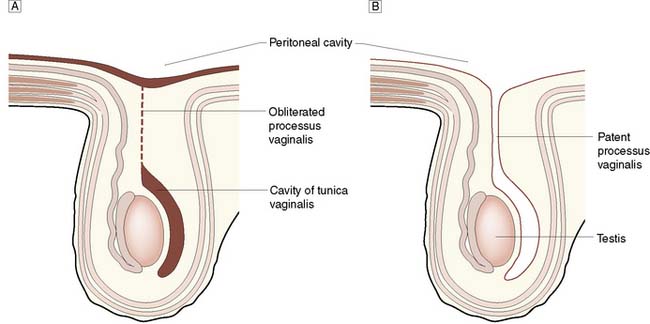

The inguinal canal is an oblique passage in the lower anterior abdominal wall, through which the spermatic cord passes to the testis in the male, or the round ligament to the labium majus in the female. The processus vaginalis traversing the canal is normally obliterated at birth, but persistence in whole or in part presents an anatomical predisposition to an indirect inguinal hernia (Fig. 11.4). The openings of the canal are formed by the internal and external rings. The internal (deep) inguinal ring is an opening in the transversalis fascia, which lies approximately 1 cm above the mid-inguinal point (midway between the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine). The internal inguinal ring is bounded medially by the inferior epigastric artery (Fig. 11.3). The inguinal canal ends at the external (superficial) inguinal ring, which is an opening in the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle just above and medial to the pubic tubercle. At birth, the internal and external rings lie on top of each other, so that the inguinal canal is short and straight; with growth, the two rings move apart so that the canal becomes longer and oblique.

Fig. 11.4 Processus vaginalis testis.

A Normal obliteration of processus vaginalis.B Persistence of patent processus.

Indirect inguinal hernia

Clinical features

The hernia forms a swelling in the inguinal canal, which may extend into the scrotum. It is often readily visible when the patient stands or is asked to cough. However, as the population becomes fatter, and patients tend to present earlier with symptoms or a small swelling, the diagnosis may not be so obvious on inspection of the groin. However, look for signs of asymmetry between the two groins. While bilateral inguinal hernias are not unusual, it is unusual for both hernias to be of similar size (Fig. 11.5). An inguinal hernia, which passes into the scrotum, passes above and medial to the pubic tubercle, in contrast to a femoral hernia, which bulges below and lateral to the tubercle (Fig. 11.6). Again, in more obese patients, such landmarks can be difficult to palpate with confidence. A cough impulse is normally palpable, and bowel sounds can often be heard within the hernia on auscultation. If there is no visible swelling, a cough impulse is sought with the patient standing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree