Chapter 15 The Abdomen

A. The Abdominal Wall

“Here too their sisters dwell.

And they are three, the Gorgons, winged,

With hair of snakes, hateful to mortals.

Whom no man shall behold and draw again

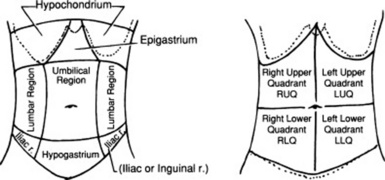

(1) Inspection

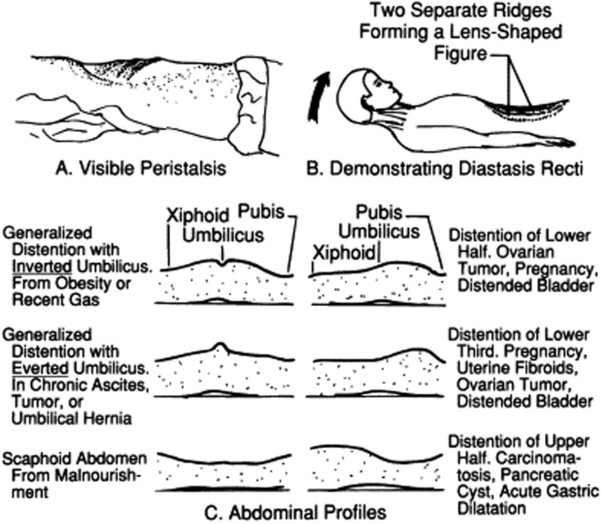

3 What are the most important contours on lateral inspection?

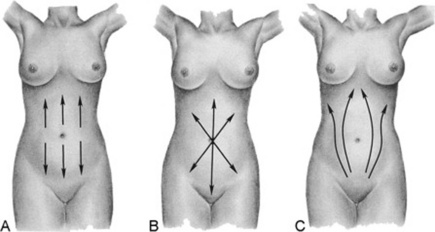

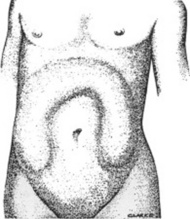

A Cupid’s bow profile is typical of acute pancreatitis, with the midpoint between the two bow branches coinciding with the umbilical retraction from localized peritonitis (Fig. 15-2).

A Cupid’s bow profile is typical of acute pancreatitis, with the midpoint between the two bow branches coinciding with the umbilical retraction from localized peritonitis (Fig. 15-2).

A discrete bulge in the epigastric area is seen in large pericardial effusions (Auenbrugger’s sign, from the name of the inventor of percussion). This lopsided protuberance should not be confused with a fat belly, which on lateral view appears instead as a convex arching of the abdominal contour, peaking at the umbilicus.

A discrete bulge in the epigastric area is seen in large pericardial effusions (Auenbrugger’s sign, from the name of the inventor of percussion). This lopsided protuberance should not be confused with a fat belly, which on lateral view appears instead as a convex arching of the abdominal contour, peaking at the umbilicus.

A localized bulge over the hypogastric area is typical of a distended urinary bladder (see Fig. 15-2).

A localized bulge over the hypogastric area is typical of a distended urinary bladder (see Fig. 15-2).

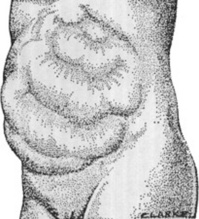

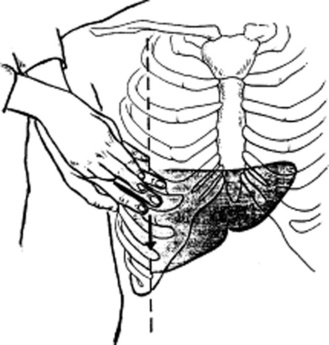

A bulge over the two upper quadrants is seen in hepatosplenomegaly (Fig. 15-3).

A bulge over the two upper quadrants is seen in hepatosplenomegaly (Fig. 15-3).

A “ladder” pattern of abdominal distention is typical of small bowel obstruction (large bowel obstruction produces instead an inverted-U pattern) (see Fig. 15-4). Visible peristaltic waves also can occur in intestinal obstruction, and when associated with abdominal distention and hyperactive bowel sounds, they argue favorably for the presence of the condition. Unfortunately, visible peristalsis is only present in 6% of patients, and decreased or absent bowel sounds are present in one quarter of cases. In fact, more than one third of intestinal obstructions do not even have abdominal distention.

A “ladder” pattern of abdominal distention is typical of small bowel obstruction (large bowel obstruction produces instead an inverted-U pattern) (see Fig. 15-4). Visible peristaltic waves also can occur in intestinal obstruction, and when associated with abdominal distention and hyperactive bowel sounds, they argue favorably for the presence of the condition. Unfortunately, visible peristalsis is only present in 6% of patients, and decreased or absent bowel sounds are present in one quarter of cases. In fact, more than one third of intestinal obstructions do not even have abdominal distention.

Figure 15-2 Lateral abdominal contours. A, Cupid’s bow of pancreatitis. B, Fat. C, Bladder distention.

(Adapted from Sapira J: The Art and Science of Bedside Diagnosis. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1990.)

Figure 15-3 The appearance of moderate distention of the large gut.

(From Silen W: Cope’s Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen, 19th ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996, with permission.)

II Evaluation of the Umbilicus

4 What are the major abnormalities of the umbilicus?

Appearance of the umbilicus can provide valuable information (Fig. 15-5). There are three possible abnormalities: (1) protuberances, (2) purplish discolorations, and (3) a shift along the vertical line.

5 What are the most common protuberances?

Primarily two: (1) an eversion of the umbilical scar and (2) the Sister Mary Joseph nodule.

7 What is Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule?

It is the most ominous of all umbilical protuberances, since it represents a metastatic node by an intra-abdominal malignancy (see Chapter 18, questions 45 and 46). It presents as a nontender, irregular, and often exfoliative protuberance, either completely replacing the umbilicus or being palpable through it. It should not be confused with an omphalith, which is another umbilical nodule, but due instead to poor personal hygiene, resulting in collection of sebum and keratin.

8 What is the significance of a purplish discoloration of the umbilicus?

It is a sign of subcutaneous intraperitoneal bleed, usually from acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis. A periumbilical ecchymosis is commonly referred to as Cullen’s sign, and it is often encountered in association with Grey Turner’s, a bilateral reddish/purplish discoloration of the flanks. Both are poorly sensitive and poorly specific markers of hemorrhagic pancreatitis (see below, questions 13 and 116).

III Abdominal Respiratory Motion

11 How should the abdominal wall behave during normal respiration?

It should be synchronized with the chest wall, so that both expand in inspiration and contract in exhalation. In respiratory muscle weakness (and impending respiratory failure), the two become instead asynchronous, with respiratory alternans and abdominal paradox (see Chapter 13, questions 52–59).

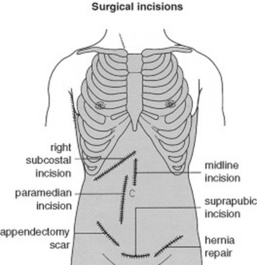

15 What about surgical scars?

Every surgical scar should be investigated and inquired about, since they can often be the telltale sign of old (and possibly current) pathology. Scars also should be reported in the patient’s record, by using a sketch to indicate their location in the four abdominal quadrants (Fig. 15-6).

V Abnormal Venous Patterns

17 How can you distinguish them?

By identifying their location and direction of blood flow (Fig. 15-8):

A superior vena cava obstruction creates a venous engorgement of the upper abdominal wall that has a downward flow.

A superior vena cava obstruction creates a venous engorgement of the upper abdominal wall that has a downward flow.

An inferior vena cava obstruction creates a venous engorgement of the lateral abdominal wall (flanks) that has an upward flow.

An inferior vena cava obstruction creates a venous engorgement of the lateral abdominal wall (flanks) that has an upward flow.

A portal system obstruction creates instead a periumbilical network of veins, with the most rostral draining upward and the most caudal draining downward.

A portal system obstruction creates instead a periumbilical network of veins, with the most rostral draining upward and the most caudal draining downward.

19 What is caput medusae?

It is the name given to the abnormal venous networks of portal hypertension. It is most commonly seen in cirrhotics whose umbilical vein has reopened (see Cruveilhier-Baumgarten murmur, disease, and syndrome, discussed in question 34). This presents with a tuft of veins radiating from the umbilicus as spikes of a wheel or a nest of snakes; hence, the name. Some of these engorged veins drain rostrally into the internal mammary, whereas others drain caudally into the inferior mammary.

29 What is the significance of an abdominal murmur/bruit?

It depends on its location. This may be either epigastric or right/left upper quadrant.

30 What is the significance of an epigastric murmur?

A systolic, medium- to low-pitched murmur over the epigastrium is not uncommon in healthy individuals. It occurs especially often in pregnancy, and, in fact, as many as one fifth of normal and thin women may have it, too (this frequency is a little lower in men). In contrast to a pathologic finding (like the murmur of renal artery stenosis, which tends to be louder outside the epigastrium [see below, questions 122 and 123]), a benign murmur is characteristically limited to the area between the xiphoid process and umbilicus. It usually originates from a normal celiac tripod.

31 What is the significance of a right or left upper quadrant murmur/bruit?

When over the right upper quadrant, it often indicates a hepatic tumor, typically a hepatoma but also a metastasis. It is due to tumoral neovascularization or extrinsic vascular compression by the cancer, but also can reflect hepatitis, cirrhosis, an arteriovenous malformation, or, occasionally, simple tricuspid regurgitation.

When over the right upper quadrant, it often indicates a hepatic tumor, typically a hepatoma but also a metastasis. It is due to tumoral neovascularization or extrinsic vascular compression by the cancer, but also can reflect hepatitis, cirrhosis, an arteriovenous malformation, or, occasionally, simple tricuspid regurgitation.

When over the left upper quadrant, it indicates instead cancer of the pancreas or a vascular anomaly of the spleen. Less frequent causes of a left (or right) upper quadrant murmur/bruit are aneurysmatic lesions of the abdominal aorta or of renal, celiac, and mesenteric vessels.

When over the left upper quadrant, it indicates instead cancer of the pancreas or a vascular anomaly of the spleen. Less frequent causes of a left (or right) upper quadrant murmur/bruit are aneurysmatic lesions of the abdominal aorta or of renal, celiac, and mesenteric vessels.

Finally, renal vascular disease of the right (or left) kidney also may produce a systolic murmur in the upper quadrants. Yet, these lesions are more commonly associated with a continuous murmur (i.e., a bruit). This can be heard, albeit less strongly, over the epigastrium, too.

Finally, renal vascular disease of the right (or left) kidney also may produce a systolic murmur in the upper quadrants. Yet, these lesions are more commonly associated with a continuous murmur (i.e., a bruit). This can be heard, albeit less strongly, over the epigastrium, too.

34 What are Cruveilhier-Baumgarten disease and Cruveilhier-Baumgarten syndrome?

The disease is a congenital patency of the umbilical vein, even though portal hypertension may be absent. Patients with this condition do not have ascites, but may have a small and atrophic liver—like the first patient described by Cruveilhier (see below, question 35).

The disease is a congenital patency of the umbilical vein, even though portal hypertension may be absent. Patients with this condition do not have ascites, but may have a small and atrophic liver—like the first patient described by Cruveilhier (see below, question 35).

The syndrome is instead typical of portal hypertension from cirrhosis and consists of either an acquired reopening of the umbilical vein or high flow in paraumbilical/anastomotic veins.

The syndrome is instead typical of portal hypertension from cirrhosis and consists of either an acquired reopening of the umbilical vein or high flow in paraumbilical/anastomotic veins.

IV Succussion Splash

37 What is a succussion splash?

It is the noise of shaking a body cavity with a large amount of air and water. Hippocrates was the first to describe it, probably in reference to a hydropneumothorax. Stressing its diagnostic value, he wrote: “You shall know that the chest contains water but not pus, if in applying the ear during a certain time on the side, you perceive a noise like that of boiling vinegar.” If elicited in the abdomen, it reflects instead an intestinal obstruction or a gastric dilation (see below, question 114). Although often detected by the unaided ear, it usually requires a stethoscope.

41 What is the difference between a light and a deep palpation?

In light palpation, the palm of the hand rests gently on the wall, while the fingers are pressed into the abdomen at a depth of 1 cm.

In light palpation, the palm of the hand rests gently on the wall, while the fingers are pressed into the abdomen at a depth of 1 cm.

Deep palpation is the same as light palpation, except that the examiner presses his or her fingers more deeply than 1 cm. This technique is usually carried out by reinforced palpation (i.e., by pushing on the fingers of the palpating hand with the fingers of the other hand [bimanual palpation]; Fig. 15-9).

Deep palpation is the same as light palpation, except that the examiner presses his or her fingers more deeply than 1 cm. This technique is usually carried out by reinforced palpation (i.e., by pushing on the fingers of the palpating hand with the fingers of the other hand [bimanual palpation]; Fig. 15-9).

42 How can one distinguish between an intra-abdominal and an intramural mass?

By palpating the mass while the patient is raising the head from the pillow. This tenses the abdominal wall muscles, thus pushing away an intra-abdominal mass but not an intra-mural mass (i.e., one localized in the abdominal wall). This technique also can be used to separate the abdominal wall from peritoneal tenderness (see below, questions 153–160).

Examples of Abnormalities Detectable On Palpation

B. Liver

“Zeus’ winged hound, an eagle red with blood,

Shall come a guest unbidden to your banquet.

All day long he will tear to rags your body,

feasting in a fury on the blackened liver.

Look for no end to this agony,

Until a God will freely suffer for you,

will take on Him your pain, and in your stead

Descend to where the sun is turned to darkness,

(1) Palpation of the Liver

46 Which edge can be palpated? How?

Only the lower edge is accessible, since the upper border is tucked deep into the rib cage and thus beyond the reach of the examiner’s fingers. To access the lower margin, ask the patient to lie supine, ideally with flexed hips and knees to better relax the abdominal wall (Fig. 15-10). To feel the edge, you can use one of three strategies, differing more in personal preference than value:

Cephalad approach: Place one hand on the patient’s abdomen, keeping the edge parallel to the rectus muscle and the fingers pointing toward the head. Place the other hand behind the patient’s back, to help support it. Then, while the patient is taking a deep breath, press the anterior hand downward and cephalad, so that the respiratory excursion of the diaphragm displaces the liver edge downward, bringing it into contact with the fingertips.

Cephalad approach: Place one hand on the patient’s abdomen, keeping the edge parallel to the rectus muscle and the fingers pointing toward the head. Place the other hand behind the patient’s back, to help support it. Then, while the patient is taking a deep breath, press the anterior hand downward and cephalad, so that the respiratory excursion of the diaphragm displaces the liver edge downward, bringing it into contact with the fingertips.

Transverse approach: Place your hand parallel to the costal margin (with fingers pointing toward the patient’s flank). This is probably not as good a maneuver as the other two, since it relies primarily on the hand’s margin, which is not as sensitive as the fingertips.

Transverse approach: Place your hand parallel to the costal margin (with fingers pointing toward the patient’s flank). This is probably not as good a maneuver as the other two, since it relies primarily on the hand’s margin, which is not as sensitive as the fingertips.

Hook technique: Point your fingers toward the patient’s feet, while trying to gently hook the liver with both hands.

Hook technique: Point your fingers toward the patient’s feet, while trying to gently hook the liver with both hands.

53 What is the hepatojugular reflux?

More of a cardiac than an abdominal maneuver. In fact, it is commonly used to unmask subclinical congestive heart failure (for its description and clinical significance, see Chapter 10, questions 106–114).

58 How can one best determine hepatic size by percussion?

Through direct or indirect percussion (Fig. 15-11). Both are carried out during quiet respiration. The direct technique consists of a light abdominal percussion by the index finger alone. Indirect percussion is instead the more traditional combination of plexor and pleximeter, as, respectively, the striking and stricken finger. The pleximeter (usually the middle finger of one hand) is applied to the abdominal wall only by its distal interphalangeal joint (to avoid dampening of vibrations); the middle finger of the other hand is then used as a plexor against the pleximeter, usually tapping along the right MCL. Even when performing indirect percussion, it is important that you tap lightly, making the note barely audible to only yourself. By doing so, you can more easily identify the hepatic area as a change in percussion note, from resonant (pulmonary parenchyma), to dull (liver), and to resonant again (air-filled bowel loops). Yet, even this may lead to inaccuracies. Vertical liver span is the distance between two resonant points along the MCL, detected during either quiet breathing, or at the same phase of respiration. Direct percussion performed by gastroenterologists has been found to be more accurate than indirect percussion, yet a normal range of liver span for this technique has not been determined. Thus, indirect percussion should still be the maneuver of choice.

60 What is the scratch test?

It is a combined auscultatory/percussive maneuver aimed at localizing the inferior hepatic border (Fig. 15-12). Place the stethoscope either beneath the xiphoid or over the liver, just above the costal margin of the MCL. Then administer “scratches” in a cephalad fashion, by moving the finger along the MCL—from the right lower quadrant toward the costal margin. The point at which the scratching sound intensifies indicates a change in underlying tissue, and thus the presence of the lower liver edge. A variation of the test is auscultatory percussion, in which the examining finger does not scratch the abdominal wall but gently percusses it (or flickers it).

63 In summary, what are the pros and cons of bedside assessment of liver size?

When compared with firm percussion, light percussion underestimates liver size, yet it is still closer to ultrasonic evaluation.

When compared with firm percussion, light percussion underestimates liver size, yet it is still closer to ultrasonic evaluation.

Measurements by direct and indirect percussion vary significantly.

Measurements by direct and indirect percussion vary significantly.

Palpability of the lower liver edge is a totally inaccurate marker of hepatomegaly.

Palpability of the lower liver edge is a totally inaccurate marker of hepatomegaly.

The scratch test needs further validation.

The scratch test needs further validation.

Liver span measured by physical exam does not correlate with the actual size of the liver.

Liver span measured by physical exam does not correlate with the actual size of the liver.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree