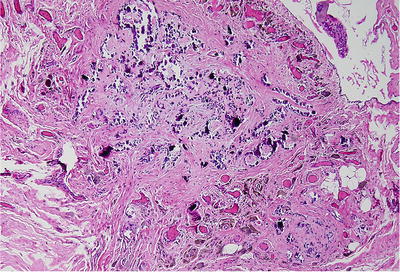

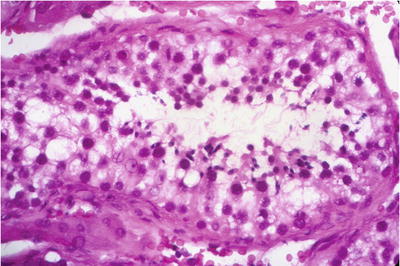

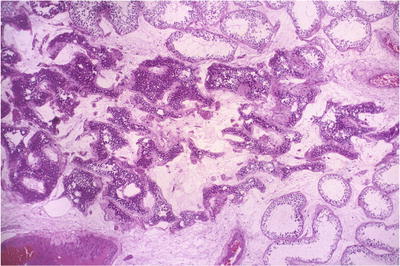

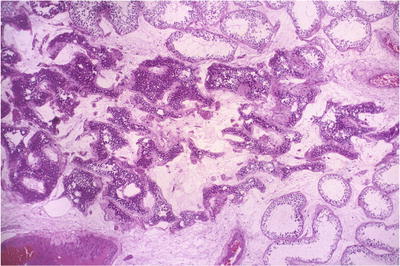

Fig. 39.1.

Cryptorchid testis in 13- year-old boy. Tubules have no germ cells and show aspermatogenesis. Right side of field has a Sertoli cell nodule.

The histologic appearance of cryptorchid testis varies with age, testicular position, and prior hormonal therapy. Human chorionic gonadotropin- or gonadotropin-releasing hormone [GnRH] is sometimes used as a hormonal means to bring the testis into the scrotum

♦

The prepubertal testis often shows a Sertoli cell nodule (Pick’s adenoma) comprised of a circumscribed collection of small tubules lined by fetal-type Sertoli cells; the testis usually contains germ cells but in decreased numbers. Following puberty, changes become more pronounced and include tunica propria thickening; reduced tubular diameter, tubular sclerosis, and interstitial fibrosis; and more prominent Leydig cell clusters

Anorchidism

Clinical

♦

This rare condition is due to the absence of both testes. It can only be distinguished clinically from cryptorchidism

♦

Unilateral anorchidism (vanishing testis syndrome) occurs in 1 in 5,000 males; bilateral testes are absent in 1 in 20,000 males. The gonad may disappear due to many causes, including intrinsic gonadal disorder, infection, trauma, torsion, infarction, or atrophy resulting from the overproduction of androgens

Macroscopic

♦

All that remains may be epididymis, vas, or a “fibrous nubbin.” If a vas deferens is identified, then an ipsilateral testis had to exist during gestation

Microscopic (Fig. 39.2)

♦

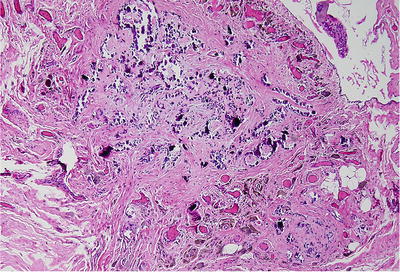

Fig. 39.2.

Congenital anorchia caused by in utero infarction. All that remains is a zone of dense fibrous tissue with dystrophic calcifications and siderophages.

The fibrous nubbin consists of dense collagen, siderophages, and dystrophic calcification

Polyorchidi sm

Clinical

♦

This is the very unusual (<80 reported cases) presence of more than two testes. Patients present with a scrotal mass that may be confused with a testicular tumor

Macroscopic

♦

The extra testis may have its own epididymis and a vas deferens that joins the other vas distally, or the testis may share a common epididymis with another testis

Microscopic

♦

The spermatogenic function of a supernumerary testis varies: the testis may be normal or have hypospermatogenesi s

Adrenal Cortical Rest

Clinical

♦

This clinically insignificant finding, identified in 4–15% of individuals, is usually an incidental finding

Macroscopic

♦

Encapsulated nodules of adrenal cortical tissue measuring a few millimeters are found in the spermatic cord, epididymis, rete testis, or tunica albuginea, and rarely within testis

Microscopic

♦

Adrenocortical tissue typically exhibits usual zonation of the adrenal tissue seen in normal cortex. Adrenal medullary tissue is not present

Splenic–Gonadal Fusion

Clinical

♦

Patients present with a scrotal or inguinal mass consisting of fused spleen and testis. It occurs in two forms: continuous fusion has a cord connecting the spleen to the fused splenic tissue/testis and discontinuous fusion has no cord. Approximately one-third of patients with the continuous form have severe congenital defects of the extremities. Enlargement occurs in conditions associated with splenomegaly

Macroscopic

♦

The splenic tissue is attached to the testicle, typically a discrete mass as large as 12 cm. In the continuous type, small aggregates of splenic tissue may be found along the length of the cord, or the entire cord may be composed of splenic tissue. Grossly, the tissue is normal spleen

Microscopic

♦

Histologic appearance is that of normal spleen and testis

Acquired Abnormalities

Testicular Torsion and Infarct

Clinical

♦

Torsion is twisting of the spermatic cord, usually within the tunica vaginalis. The twisting obstructs veins, and the testis becomes hemorrhagic. Eventually, the arterial flow is interrupted and infarction occurs. Predisposing conditions include absence of scrotal ligaments, shortened attachment of peritoneal ligaments, incomplete descent, and testicular atrophy. Torsion mostly occurs in children and young adults who present with marked testicular pain. It may develop after physical activity

♦

Prompt intervention is necessary to prevent infarction. Detorsion should be performed within 6–8 h of torsion to prevent the loss of the testis. Infarction is almost certain if torsion is not corrected within 24 h. Detorsion may be attempted manually, but it may require surgical intervention (orchidopexy)

♦

The diagnosis is usually evident by history and exam, but Doppler studies or nuclear-based perfusion scans may be useful to show decreased blood flow in torsion (vs. increased blood flow in epididymitis/inflammatory conditions)

Macroscopic

♦

Gross examination reveals a swollen, blood-filled testis

♦

Up to 6 h after torsion, the testis shows venous congestion and interstitial hemorrhage. At 9 h, neutrophils marginate from the capillaries, and severe interstitial hemorrhage is present. After 1–2 days, hemorrhagic infarction develops. Vasculopathy (the blood vessel damage) with hemorrhage and necrosis is a manifestation of intermittent torsion and can clinically mimic a neoplasm or be mistaken for primary vasculitis

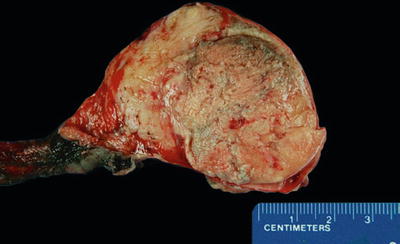

Fig. 39.3.

Infarct of the testis in a 75-year-old man with testicular trauma. Orchiectomy 4 weeks later shows shadow outlines of tubules. Inset (left) has necrotic cell debris filling tubular lumen.

Varicocele

Clinical

♦

Varicocele is thought to be the result of insufficient venous valves. It results from abnormal dilatation and tortuosity to the veins of the pampiniform plexus of spermatic cord. Varicocele primarily involves the left side (90% of cases) or may be bilateral (10%). It is associated with infertility, and a number of hypotheses have been posited regarding this association, including endocrinologic insufficiency, venous stasis, resulting in a buildup of toxic metabolites and decreased oxygenation, and increased temperature due to blood flow

♦

Ligation of the left spermatic vein may correct varicocele and fertility. Fertility returns in up to 55% of patients undergoing ligation

Macroscopic

♦

Rarely seen by pathologists; the lesion consists of tortuous and dilated veins of the pampiniform plexus

♦

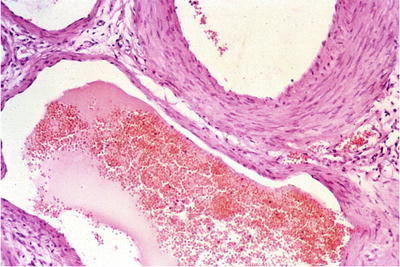

Multiple channels of dilated spermatic vein are often surrounded by fibrosis. Testicular biopsy shows hypospermatogenesis (see below) with germ cell sloughing and Leydig cell hyperplasia. Histologic changes may revert to normal after spermatic vein ligation

Fig. 39.4.

Varicocele shows dilated venous channels.

Infections and Inflammatory Conditions of Testis and Epididymis

Viral Orchiepididymitis

Clinical

♦

Mumps is the most common viral etiology of orchiepididymitis. Next in frequency are Coxsackie B, influenza, EBV, echovirus, adenovirus, varicella, vaccinia, rubella, and dengue. HIV may involve the testis and is characterized by a lymphocytic infiltrate

♦

Usually, viral orchitis occurs as a complication of up to 35% of adult mumps. It is infrequent in children. Men with unilateral involvement usually maintain fertility. However, it is bilateral in 25% of cases, and this bilateral involvement often leads to infertility. Testicular involvement typically becomes evident in 4–6 days after parotid involvement

Macroscopic

♦

The testis appears normal at the early stage, but if involvement is severe, atrophic changes develop

Microscopic

♦

Changes are multifocal and characterized by lymphocytic infiltrates of the interstitium and intratubular accumulations of macrophages with lesser numbers of neutrophils. There is loss of germ cells; ultimately, tubular sclerosis and interstitial fibrosis develop

Bacterial Orchiepididymitis

Clinical

♦

In younger men, acute and chronic bacterial orchitis is most often attributable to Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea, representing common causes of male infertility (see below). In older men, Escherichia coli from associated urinary tract infection is the most common etiologic agent. Other responsible agents seeding from other sites via the lymphatics or the blood are Klebsiella sp., Streptococci, Staphylococci, Pneumococci, Salmonella enteritidis, and Actinomyces israelii

♦

Brucellosis involves the testis and epididymis in 20% of all cases. Brucellosis is characterized by a testicular mass with constitutional symptoms (undulating fever, malaise, headache, and sweats). Complications include an abscess with involvement of the scrotum and scrotal sinus formation

Fig. 39.5.

The testis of a 14-year-old boy with severe acute and chronic orchiepididymitis. There is testicular swelling with a pale, yellow cut surface caused by a purulent exudate.

Microscopic

♦

Polymorphonuclear leukocyte inflammatory infiltrates involving interstitium and seminiferous tubules, progressing to abscess. Brucellosis causes an infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes with occasional granulomas

Granulomatous Orchiepididymitis

Mycobacterial Orchiepididymitis

Clinical

♦

Testicular involvement by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is always secondary to infection elsewhere in the body. In adults, tuberculous orchitis typically occurs as a descending infection from other genitourinary sites. Renal tuberculosis results in bladder and prostatic involvement, with subsequent spread to the epididymis and testis. Most patients are adults. In children, involvement usually occurs by hematogenous spread from the lung. Patients may have constitutional symptoms but usually present with only testicular swelling and pain

♦

The testis may be enlarged with multiple soft, nodular, white caseating granulomas that typically are a few millimeters in size or may coalesce. Fistulae may extend to the scrotum

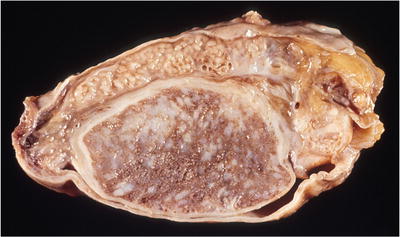

Fig. 39.6.

Tuberculous orchitis and epididymitis. Both organs are expanded by numerous yellow nodules.

Microscopic

♦

Necrotizing and nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammation is present. Granulomas contain histiocytes, giant cells, and lymphocytes in a fibrotic stroma that surrounds necrotic material. The inflammatory process is destructive of testicular parenchyma

Fungal Orchiepididymitis

Clinical

♦

Rarely, fungal infections involving the genitourinary tract may occur in immunocompromised patients. Fungal organisms that can cause orchitis include Blastomyces hominis, Coccidioides immitis, Histoplasma capsulatum, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes

Macroscopic

♦

Necrotic granulomas and abscesses are present

Microscopic

♦

Histologic features are identical to those of fungal infections occurring elsewhere. Necrotizing and nonnecrotizing granulomas and neutrophilic microabscesses are present. Organisms may be identified using special stains, such as methenamine silver or periodic acid-Schiff stain s

Syphilitic Orchiepididymitis

Clinical

♦

Congenital and acquired forms occur. In congenital syphilis, testicular enlargement is present at birth. In the acquired form, the testes are involved in tertiary syphilis

Macroscopic

♦

In infants, the testes are enlarged; over time, the testes become fibrotic and small. In adults, the testes are soft, yellow, and necrotic. Gummas may be present

Microscopic

♦

Testes involved by congenital syphilis exhibit interstitial inflammation with abundant plasma cells. Arteries show obliterative endarteritis and destructive inflammation; over time, the testes become fibrotic

Acquired (or tertiary) syphilis has two histologic patterns: interstitial orchitis and gummatous orchitis. Interstitial orchitis is identical to that seen in congenital syphilis and ultimately leads to small fibrotic testes. Gummatous orchitis is characterized by coagulative necrosis with a peripheral zone of fibrous tissue containing lymphocytes, plasma cells, and occasional giant cells. Both gummas and interstitial orchitis may occur in the same testis. Spirochetes may be seen with special silver stains (Warthin–Starry, Dieterle)

Leprosy

Clinical

♦

Leprosy is a very rare cause of infertility in the USA but more frequent in other parts of the world. The testes are involved because the low temperature within the scrotum facilitates the growth of bacilli

Macroscopic

♦

The gross appearance of testes is dependent on the stage of infection. In early stage, they may look normal, but in later stages, testes are small and fibrotic

Microscopic

♦

Three phases of testicular leprosy:

Early phase: a vascular phase characterized by lepra cells containing numerous organisms within blood vessel walls and testicular interstitium

This is followed by an interstitial phase with obliterative endarteritis, interstitial fibrosis, and lepra cells

Finally, there is obliterative phase characterized by a loss of testicular parenchyma and replacement by fibrous tissue

Sarcoidosis

Clinical

♦

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease of unknown cause and involves the genitourinary system in 0.2% of all cases. Only a few cases involving the testes have been reported, and these tend to be unilateral

Macroscopic

♦

Small nodules may be present

Microscopic

♦

Nonnecrotizing granulomas are present, identical to sarcoid granulomas, and histologically, one must exclude a granulomatous reaction due to seminoma, mycobacterial infection, or idiopathic granulomatous orchitis

Malakoplakia

Clinical

♦

This unusual form of bacterial infection most commonly affects the bladder in middle-aged women. However, in men, the testes are involved in 12% of cases of genitourinary malakoplakia. Patients have a defect in the capacity of their mononuclear cells to kill phagocytized bacteria. Inflammation is histiocytic and forms masses. Infection is due to coliform bacteria such as E. coli (most common), Proteus vulgaris, Klebsiella pneumonia, and others

Macroscopic

♦

The testes are enlarged, with yellow, soft parenchyma

Microscopic

♦

There are aggregates of histiocytes with abundant, foamy, slightly granular cytoplasm. Some of the histiocytes contain Michaelis–Gutmann bodies, which are intracytoplasmic calcific concretions with a target-like appearance. These cause tubular destruction

I diopathic Granulomatous Orchitis

Clinical

♦

Clinically and pathologically, this is a granulomatous inflammatory disorder of older males. Hypotheses for etiology include infection or autoimmune orchitis. The lesion presents as a unilateral tender testicular mass mimicking a tumor. Rare cases have been bilateral; 66% of patients who have symptoms have a urinary tract infection

Macroscopic

♦

The testis is enlarged and nodular, with white to yellow homogeneous parenchyma and areas of necrosis. Grossly, it resembles lymphoma, a leukemic infiltrate, or malakoplakia

♦

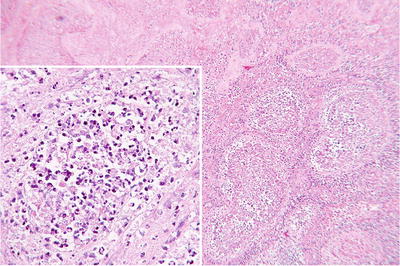

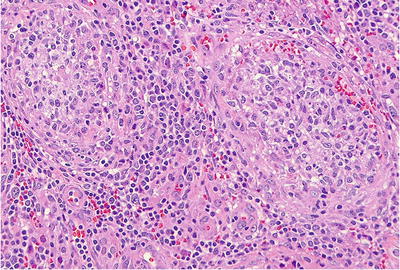

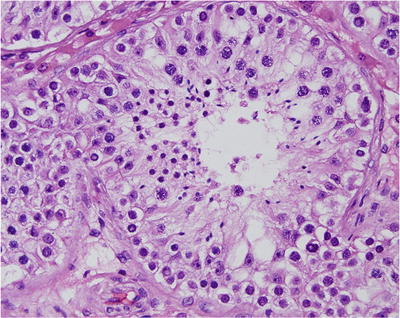

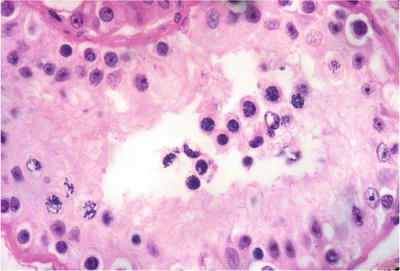

Inflammation may primarily involve tubules (tubular orchitis) or interstitium (interstitial orchitis). In tubular orchitis, inflammatory cells (plasma cells and lymphocytes) ring seminiferous tubules, and there is a loss of germ cells: epithelioid histiocytes with or without giant cells populate the tubules; inflammation is associated with vascular thrombosis and vasculitis. In interstitial orchitis, inflammation is interstitial. In both forms, a loss of tubules and fibrosis occurs as a result of inflammation

Fig. 39.7.

Idiopathic granulomatous orchitis with collections of epithelioid histiocytes filling seminiferous tubules and a chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the interstitium.

Infertility

♦

In men who are azoospermic (no sperm) or oligospermic (decreased sperm), open testicular biopsy has been the standard method to assess spermatogenesis. However, fine-needle aspiration cytology, a less invasive method, has been shown to correlate with biopsy in 94% of cases, its only limitation being that tubular basement membrane status is not assessed (Meng et al. 2001). By either approach, the pathologist can recognize six diagnostic patterns:

Normal or nearly normal

Hypospermatogenesis

Aspermatogenesis

Early maturation arrest

Late maturation arrest

Tubular hyalinization (evaluable in biopsy only)

Normal or Nearly Normal

♦

This pattern is due to excurrent duct obstruction (blockage of ducts leading away from the testis)

Clinical

♦

Approximately 10% of biopsied infertile patients have normal histology. Patients have azoospermia, normal-sized testes, and normal spermatogenesis on a testicular biopsy. Sperm motility may be impaired. Obstruction can be the result of congenital atresia of the vas deferens or epididymis, cystic fibrosis, or acquired by infection or surgical ligation (vasectomy)

Young syndrome is a lesion at the junction of the head and body of the epididymis in which the ductus epididymidis is blocked by thick fluid. Patients also have sinusitis and bronchiectasis as in children with cystic fibrosis

Macroscopic

♦

No alterations are seen

♦

Spermatogenesis is normal for many years following obstruction. The epididymis has the ability to store and phagocytize sperm and sperm products at a rate that matches sperm production

Testicular biopsy shows active spermatogenesis. After vasovasostomy (reversal of vasectomy), there may be some germinal cell disorganization and sloughing, variable amounts of tunica propria thickening, and occasional interstitial fibrosis. Vasitis nodosa may be seen

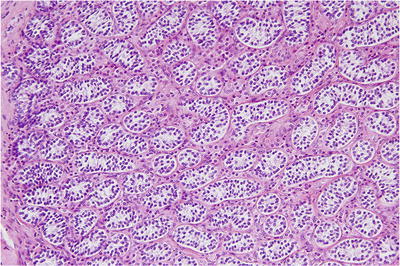

Fig. 39.8.

Normal testis. Tubular profile shows spermatogonia at the periphery with maturation progression toward the lumen of primary spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa.

Hypospermatogenesis

Clinical

♦

This is the second most common cause of testicular infertility. Patients are potent and have normal secondary sexual characteristics but are oligospermic. Germ cells and developing forms are present in normal proportions, but overall numbers are decreased

It is usually idiopathic but can be related to partial androgen receptor unresponsiveness (Reifenstein syndrome), the aftereffect of cryptorchidism in formerly cryptorchid patients after orchidopexy, or exposure to toxins, excess heat, varicocele, or hormonal dysfunction including hypothyroidism

Macroscopic

♦

No alterations are evident

♦

There is an overall thinning of the germinal epithelium with proportional hypoplasia of spermatogonia, primary spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa (sperm with tail). There may be diffuse Leydig cell hyperplasia

Fig. 39.9.

Hypospermatogenesis . Primary spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa can be found but in reduced numbers. Courtesy of Dr. W. M. Murphy, Gainesville, FL.

Aspermatogenesis

♦

This is most often the result of the Sertoli cell-only syndrome (absence/aplasia of germ cells). The condition is usually idiopathic or secondary to prior chemotherapy or radiation treatment. Estrogen excess may be an additional cause

Clinical

Patients are potent, with normal secondary sexual characteristics, but azoospermic. Follicle-stimulating hormone levels are always high as a result of the absence of spermatogenesis

Macroscopic

♦

No alterations are usually present, although occasionally, the testes are smaller than normal

♦

Seminiferous tubules show a moderate decrease in diameter and are devoid of germ cells. Only Sertoli cells remain. In a few cases , some tubules show spermatogenesis, so the diagnosis is germ cell aplasia with focal spermatogenesis

♦

This pattern also prevails in the following entities:

Androgen insensitivity (testicular feminization) syndrome: a phenotypic female but genetic male with normal or elevated testosterone levels. Testes are present in the abdomen, inguinal canal, or labia majora and are removed after puberty to prevent tumors. The size of the testes varies. In most cases, tubules have Sertoli cells only (Fig. 39.11)

Cryptorchid testes may present with this pattern, although early maturation arrest is more common

In hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, this pattern occurs with greatly increased numbers of Sertoli cells

♦

Mixed atrophy: a variant in which some testicular lobules have aspermatogenesis with Sertoli cells only, while others have normal tubules w ith spermatogenesis

Fig. 39.10.

Sertoli cell-only syndrome . The tubule is lined entirely by uniform, columnar Sertoli cells. Germ cells are absent.

Fig. 39.11.

Androgen insensitivity (testicular feminization) syndrome . Seminiferous tubules contain only small, fetal-type Sertoli cells, surrounded by Leydig cells. In one-third of patients, spermatogonia are present.

Early Maturation Arrest

Clinical

♦

Also called premeiotic or “complete” maturation arrest; this is the most common cause of testicular infertility. Patients are potent, with normal secondary sexual characteristics, but they are oligospermic or azoospermic. The cause is usually idiopathic, but cryptorchidism, alcoholism, exposure to toxins, and postpubertal gonadotropin deficiency can result in a similar pattern. In adulthood, cryptorchid testes most often show this pattern but may also show aspermatogenesis

Macroscopic

♦

No alterations are evident

♦

Spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes are present but no spermatids or spermatozoa (sperm with tail). Biopsy shows <17 spermatogonia per tubular profile

Fig. 39.12.

Early maturation arrest . Only spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes are seen, some with mitotic figures (lower left). The lumen is devoid of spermatids or spermatozoa. Courtesy of Dr. W. M. Murphy, Gainesville, FL.

Late Maturation Arrest

Clinical

♦

In some patients with oligospermia or azoospermia, this pattern is seen, also called postmeiotic or “incomplete” maturation arrest

Macroscopic

♦

No alterations are evident

Microscopic

♦

There are primary spermatocytes and spermatids but absent or markedly decreased spermatozoa (sperm wit h tail )

Tubular Hyalinization (Evaluable in Biopsy Only)

Clinical

♦

Klinefelter syndrome and other karyotypic abnormalities cause dysgenetic hyalinization. It is the result of an abnormal number of X chromosomes, commonly with genotype of 47, XXY and primary gonadal insufficiency. Approximately 1 in 1,000 newborns is affected. Males have a eunuchoid phenotype with tall stature, incomplete virilization (poorly developed secondary sex characteristics), and gynecomastia and may have mental retardation; phenotypic and testicular changes become evident at puberty. They have an increased incidence of breast cancer and extragonadal germ cell tumors of the mediastinum

Macroscopic

♦

The testes are usually small and firm (<2.5 cm in greatest dimension)

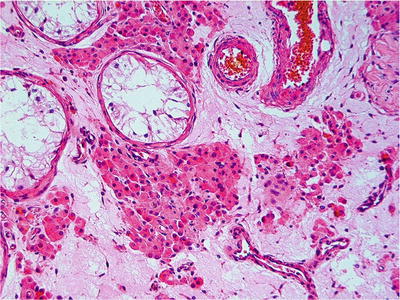

♦

The t estes show progressive failure of spermatogenesis with a loss of germ cells and Sertoli cells. The tunica of tubules thickens, and eventually all that remains are hyalinized empty tubules lacking elastic fibers. Leydig cell clusters become more prominent. It is debatable whether this represents Leydig cell hyperplasia or prominence of Leydig cells as a result of testicular volume loss

♦

Other causes of tubular hyalinization:

Hormonal deficit and hypopituitarism of pre- or postpubertal onset

Estrogen excess (endogenous, from cirrhosis or estrogen-producing tumor of adrenal, exogenous causes, as prostate cancer therapy)

Androgen excess, either endogenous from adrenogenital syndrome or an androgen-producing tumor or exogenous

Glucocorticoid excess, either endogenous from Cushing syndrome or exogenous from steroid therapy

Hypothyroidism

Ischemia due to torsion or to severe atherosclerosis

♦

Postobstructive change results in a mosaic of normal and hyalinized tubules. This is usually secondary to varicocele of pampiniform plexus or disorders involving dilatation of the rete testis. It follows infection (mumps or Coxsackie B orchitis) and can be due to physical and chemical agents (lead, carbon disulfide, radiation, chemothera py, or Addison’s disease)

Fig. 39.13.

Tubular hyalinization with Leydig cell prominence, a pattern seen in Klinefelter syndrome and postpubertal cryptorchid testes.

Neoplasms of the Testis (See Table 39.1 )

Table 39.1.

Differential Diagnosis of Germ Cell Tumors

Correct diagnosis→: Findings that rule out ↓: | Seminoma | Embryonal carcinoma | Yolk sac tumor | Sertoli cell tumor | Lymphoma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Seminoma | Few lymphocytes or granulomas; form glands or papillae; CD30+, SOX2+, CD117 mostly−, D2-40− | More variable nuclei, focal microcysts lined by flat cells, hyaline globules, bandlike basement membrane deposits; more than just borderline elevation of serum AFP; CK AE1/3+, AFP+, OCT3/4−, GPC3+ | Usually forms tubules; can have clear cells but smaller nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli; no GCNIS; inhibin+/−, OCT3/4−, PLAP− | Both may have intertubular growth; lack square nuclei; may have plasmacytoid chromatin; no GCNIS; often bilateral; usually CD20+, CD45+, OCT3/4− | |

Embryonal carcinoma | May have focal necrosis, but has squared-off nuclei, often clear cytoplasm, fibrovascular septa, with lymphocytes, CD30–, CK AE1/3–, SOX2–, CD117+, D2-40 (podoplanin)+ | Focal microcysts lined by flat cells, hyaline globules, bandlike basement membrane deposits, OCT3/4– | |||

Yolk sac tumor | Microcystic pattern has edema in spaces, but cysts are lined by cytologic seminoma cells (not flat cells); AFP–, CK AE1/3–, OCT3/4+ | ||||

Sertoli cell tumor | Squared-off nuclei, usually no tubules, inhibin–, OCT3/4+ | ||||

Lymphoma | Intertubular pattern exists but has square nuclei, fibrovascular septa; possibly granulomas, lacks plasmacytoid chromatin; unilateral; CD20–, CD45–, OCT3/4+ |

Gross Processing of an Orchiectomy Specimen

♦

Because the testicular tunica albuginea is impermeable to fixative, placing it directly into fixative will cause autolysis. Instead, the testis should be at least bisected prior to fixation. Even in normal testis, fixation artifact can create areas that resemble tumor (Fig. 39.14)

Fig. 39.14.

Incomplete fixation resulting in pseudohyperchromasia of the central portion of a benign testicular specimen.

♦

A margin section of spermatic cord should be taken before the tumor is sampled to avoid contamination of the margin by artifactual tumor implantation. About one block should be submitted per centimeter of the greatest dimension of tumor, plus one section to include the testicular hilum. This is because extratesticular extension is present in 16% of cases and occurs at the hilum in 91% of these

Germ Cell Tumors

Cell of Origin

♦

The precursor of postpubertal invasive germ cell tumors is germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS). Differentiated forms of intratubular germ cell tumors are also seen, most commonly intratubular seminoma or intratubular embryonal carcinoma (in 24% of cases with embryonal carcinoma)

♦

It is hypothesized that seminomas arise from GCNIS and that many nonseminomas develop from seminoma, but nonseminomatous germ cell tumors too can arise from GCNIS

♦

GCNIS does not give rise to the spermatocytic seminoma or to the pediatric forms of yolk sac tumor or teratoma

♦

Seminoma cells and GCNIS are identical morphologically and share many other features, including karyotypic abnormalities, high DNA content, ultrastructure, and immunohistochemical profile

Risk of Germ Cell Tumors

♦

Germ cell tumors comprise 95% of testicular tumors. Certain conditions increase the risk of germ cell tumors in men:

Cryptorchidism (about 4×), history of a prior testicular tumor, first-degree relative with a germ cell tumor, gonadal dysgenesis, and androgen insensitivity syndrome. Patients with history of cryptorchidism may get 1–3 biopsies bilaterally at age 18 for early detection of GCNIS

Ancillary Stains

♦

See Table 39.2

Table 39.2.

Immunohistochemical Pro files of Testicular Germ Cell Tumors

Tumor | OCT3/4 a | CD117 (c–kit) | CK b | hCG c | Vimentin | PLAP | SALL4 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Seminoma, GCNIS | + | +e | −/+ | ± | + | + | + |

Spermatocytic seminoma | − | +e | −/+ | – | – | – | ± |

Embryonal carcinoma | + | − | + | – | – | + | + |

Yolk sac tumor | − | − | + | – | + | + | + |

Teratoma | − | − | + | – | + | ± | ± |

Choriocarcinoma | − | − | + | + | – | ± | − |

Staging

♦

The TNM staging system for testicular germ cell tumors is shown at the end of the chapter. Vascular invasion or tunica vaginalis invasion is required to raise the stage from T1 to T2. Do not overcall vascular invasion; tumor cells must be attached to a vessel wall or closely conform to its shape rather than having a “floating” intraluminal pattern that represents implantation artifact

♦

The hilum should be sampled in all orchiectomies with tumor

Treatment

♦

Seminoma

Clinical stage I tumors and nonbulky stage II tumors may be treated by radical orchiectomy and radiation to ipsilateral para-aortic and pelvic lymph nodes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree