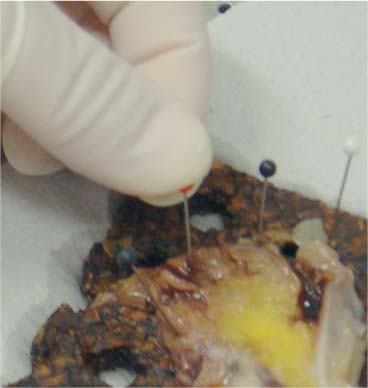

6 Technical Considerations Proper orientation and cut-up of the surgical specimen is essential in obtaining representative large sections. In the ideal situation, the rectal amputates (Fig. 6.1) or other colorectal resection preparations are first cleaned and filled with fixative, closed by sutures or clips at both ends, and then immersed in the proper amount of fixative in a container larger than the specimen. This procedure offers optimal fixation of the tissue, both in the inner and outer layers of the intestine. If the fixation is carried out only by immersing the specimen in a small amount of formalin, autolytic changes takes place that disturb the microscopic evaluation. This may also be prevented if the specimen is opened longitudinally on its front side. Cutting through the lesions or distorting them by forcing the specimen into an inappropriately small container should be avoided as it may substantially influence the macroscopic and subgross appearance of the lesion, sometimes making correlation of the large-section image with the original endoscopic image impossible. Close inspection of the specimen, especially of the frontal (Fig. 6.2) and the mesorectal (Fig. 6.3) surfaces, helps the pathologist in planning the dissection. Macroscopically seen tumor tissue on these surfaces has to be histologically documented, one of the advantages of large sections. Clinical information about the position of the tumor within the specimen is also helpful as it directs the attention of the pathologist to the most important part of the specimen. We recommend serial sectioning of the specimen perpendicular to the longitudinal axis (demonstrated in Figs. 6.4–6.7). The slices must be 3- to 5-mm thick to allow proper dehydration and further laboratory processing. This thickness is relatively easy to achieve if the specimen is properly fixed and if a sharp instrument with a disposable blade is used. Cutting up the specimen without prior fixation may reduce laboratory turnover time for this type of preparation, but it requires substantial experience. Fig. 6.1 A rectal amputation specimen closed by sutures at the distal end and by clips at the proximal end, filled with fixative. This procedure assures proper preservation of the histologic details. Fig. 6.2 The ventral, partly peritonealized, anatomic surface of the rectal specimen. The presence of peritoneum on this surface guides the pathologist in proper orientation of the specimen. Fig. 6.3 The mesorectal surface of the specimen shown in Fig. 6.2. This surface is artificial, produced by surgery. Proper visualization of this surface in the large section is essential for evaluation of the result and quality of the surgical intervention. Fig. 6.4 Fig. 6.5 Figs. 6.4–6.6 Serial slicing of the specimen perpendicular to the longitudinal axis. A knife with a very sharp disposable blade is needed for producing evenly thick 3–5-mm slices. Fig. 6.7 The serial slicing of the specimen illustrated in the previous figures provides an accurate, ordered display of all grossly detectable lesions within the specimen. A thorough naked-eye examination of the sections, especially of the cut surfaces, is essential in choosing the proper slice for embedding. The pathologist should find the slice with the deepest level of invasion. Additional slices with abnormalities not seen in the slice with the deepest invasion are also selected for embedding. The slices should be palpated since palpation and macroscopic examination of the pericolic-perirectal fatty tissue are necessary in order to find all the lymph nodes. The selected tissue slices are stretched on a cork plate and pinned, with the surface to be cut facing down (Figs. 6.8–6.11). The slices are immersed in dishes containing standard formalin solution for tissue fixation (Fig. 6.11). If the specimen was already properly fixed before slicing, the fixation time of the slice is reduced to 2–5 h. If the specimen was sliced unfixed, the fixation time for the slice is 12–24 h. By fixing the tissue when it is stretched, a fairly flat surface can be achieved. Thorough fixation of the slices is essential in this technique. Microwave treatment can considerably reduce the time necessary for optimal fixation. After fixation, the slices are removed from the cork plate and placed into special-sized containers in an automatic tissue processor (Figs. 6.12 and 6.13). Before processing, slices that are already fixed can be trimmed to obtain the ideal thickness of 3–4 mm throughout the entire slice. Formation of large paraffin blocks for embedding of the slices is demonstrated in Figures 6.14–6.19. The size of the block can be slightly modified depending on the size of the tissue slice. Sectioning of the large blocks is carried out using a special macrotome (Figs. 6.20 and 6.21). The most important factor in obtaining large histologic sections of proper quality is a skillful and experienced technician (Figs. 6.22–6.26).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree