T

Tachycardia

Easily detected by counting the apical, carotid, or radial pulse rate, tachycardia is a heart rate greater than 100 beats/minute. The patient with tachycardia usually complains of palpitations or a “racing” heart. This common sign normally occurs in response to emotional or physical stress, such as excitement, exercise, pain, anxiety, and fever. It may also result from the use of stimulants, such as caffeine and tobacco. However, tachycardia may be an early sign of a lifethreatening disorder, such as cardiogenic, hypovolemic, or septic shock. It may also result from a cardiovascular, respiratory, or metabolic disorder or from the effects of certain drugs, tests, or treatments. (See What happens in tachycardia, page 644.)

If you detect tachycardia, first perform an electrocardiogram (ECG) to check for reduced cardiac output, which may initiate or result from tachycardia. Take the patient’s other vital signs and determine his level of consciousness (LOC). If the patient has increased or decreased blood pressure and is drowsy or confused, administer oxygen and begin cardiac monitoring. Insert an I.V. catheter for fluid, blood product, and drug administration, and gather emergency resuscitation equipment.

If you detect tachycardia, first perform an electrocardiogram (ECG) to check for reduced cardiac output, which may initiate or result from tachycardia. Take the patient’s other vital signs and determine his level of consciousness (LOC). If the patient has increased or decreased blood pressure and is drowsy or confused, administer oxygen and begin cardiac monitoring. Insert an I.V. catheter for fluid, blood product, and drug administration, and gather emergency resuscitation equipment.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient’s condition permits, take a focused history. Find out if he has had palpitations before. If so, how were they treated? Explore associated symptoms. Is the patient dizzy or short of breath? Is he weak or fatigued? Is he experiencing episodes of syncope or chest pain? Next, ask about a history of trauma, diabetes, or cardiac, pulmonary, or thyroid disorders. Also, obtain an alcohol and drug history, including prescription, over-the-counter, and illicit drugs.

Inspect the patient’s skin for pallor or cyanosis. Assess pulses, noting peripheral edema. Finally, auscultate the heart and lungs for abnormal sounds or rhythms.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Besides tachycardia, this syndrome causes crackles, rhonchi, dyspnea, tachypnea, nasal flaring, and grunting respirations. Other findings include cyanosis, anxiety, decreased LOC, and abnormal chest X-ray findings.

♦ Adrenocortical insufficiency. In this disorder, tachycardia is commonly accompanied by a weak pulse as well as progressive weakness and fatigue, which may become so severe that the patient requires bed rest. Other signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, altered bowel habits, weight loss, orthostatic hypotension, irritability, bronze skin, decreased libido, and syncope. Some patients report an enhanced sense of taste, smell, and hearing.

♦ Alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Tachycardia can occur with tachypnea, profuse diaphoresis, fever, insomnia, anorexia, and anxiety. The patient is characteristically anxious,

irritable, and prone to visual and tactile hallucinations.

irritable, and prone to visual and tactile hallucinations.

What happens in tachycardia

Tachycardia represents the heart’s effort to deliver more oxygen to body tissues by increasing the rate at which blood passes through the vessels. This sign can reflect overstimulation within the sinoatrial node, the atrium, the atrioventricular node, or the ventricles.

Because heart rate affects cardiac output (cardiac output = heart rate × stroke volume), tachycardia can lower cardiac output by reducing ventricular filling time and stroke volume (the output of each ventricle at every contraction). As cardiac output plummets, arterial pressure and peripheral perfusion decrease. Tachycardia further aggravates myocardial ischemia by increasing the heart’s demand for oxygen while reducing the duration of diastole—the period of greatest coronary blood flow.

♦ Anaphylactic shock. In life-threatening anaphylactic shock, tachycardia and hypotension develop within minutes after exposure to an allergen, such as penicillin or an insect sting. Typically, the patient is visibly anxious and has severe pruritus, perhaps with urticaria and a pounding headache. Other findings may include flushed and clammy skin, a cough, dyspnea, nausea, abdominal cramps, seizures, stridor, change or loss of voice associated with laryngeal edema, and urinary urgency and incontinence.

♦ Anemia. Tachycardia and bounding pulse are characteristic signs of anemia. Associated signs and symptoms include fatigue, pallor, dyspnea and, possibly, bleeding tendencies. Auscultation may reveal an atrial gallop, a systolic bruit over the carotid arteries, and crackles.

♦ Anxiety. A fight-or-flight response produces tachycardia, tachypnea, chest pain, nausea, and light-headedness. The symptoms dissipate as anxiety resolves.

♦ Aortic insufficiency. Accompanying tachycardia in this disorder are a “water-hammer” bounding pulse and a large, diffuse apical heave. Severe insufficiency also produces widened pulse pressure. Auscultation reveals a hallmark decrescendo, high-pitched, and blowing diastolic murmur that starts with the second heart sound and is heard best at the left sternal border of the second and third intercostal spaces. An atrial or ventricular gallop, an early systolic murmur, an Austin Flint murmur (apical diastolic rumble), or Duroziez’s sign (a murmur over the femoral artery during systole and diastole) may also be heard. Other findings include angina, dyspnea, palpitations, strong and abrupt carotid pulsations, pallor, and signs of heart failure, such as crackles and neck vein distention.

♦ Aortic stenosis. Typically, this valvular disorder causes tachycardia, an atrial gallop, and a weak, thready pulse. Its chief features, however, are exertional dyspnea, angina, dizziness, and syncope. Aortic stenosis also causes a harsh, crescendo-decrescendo systolic ejection murmur that’s loudest at the right sternal border of the second intercostal space. Other findings include palpitations, crackles, and fatigue.

♦ Cardiac arrhythmias. Tachycardia may occur with an irregular heart rhythm. The patient may be hypotensive and report dizziness, palpitations, weakness, and fatigue. Depending on his heart rate, he may also exhibit tachypnea, decreased LOC, and pale, cool, clammy skin.

♦ Cardiac contusion. The result of blunt chest trauma, a cardiac contusion may cause tachycardia, substernal pain, dyspnea, and palpitations. Assessment may detect sternal ecchymoses and a pericardial friction rub.

♦ Cardiac tamponade. In life-threatening cardiac tamponade, tachycardia is commonly accompanied by paradoxical pulse, dyspnea, and tachypnea. The patient is visibly anxious and restless and has cyanotic, clammy skin and distended jugular veins. He may develop muffled heart sounds, a pericardial friction rub, chest pain, hypotension, narrowed pulse pressure, and hepatomegaly.

♦ Cardiogenic shock. Although many features of cardiogenic shock appear in other types of shock, they’re usually more profound in this type. Accompanying tachycardia are a weak, thready pulse; narrowed pulse pressure; hypotension; tachypnea; cold, pale, clammy, and cyanotic skin; oliguria; restlessness; and altered LOC.

♦ Cholera. This infectious disease is marked by abrupt watery diarrhea and vomiting. Severe fluid and electrolyte loss leads to tachycardia, thirst, weakness, muscle cramps, decreased skin turgor, oliguria, and hypotension. Without treatment, death can occur within hours.

♦ Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Although clinical findings vary widely in this

disorder, tachycardia is a common sign. Other characteristic findings include cough, tachypnea, dyspnea, pursed-lip breathing, accessory muscle use, cyanosis, diminished breath sounds, rhonchi, crackles, and wheezing. Clubbing and barrel chest are usually late findings.

disorder, tachycardia is a common sign. Other characteristic findings include cough, tachypnea, dyspnea, pursed-lip breathing, accessory muscle use, cyanosis, diminished breath sounds, rhonchi, crackles, and wheezing. Clubbing and barrel chest are usually late findings.

♦ Diabetic ketoacidosis. This life-threatening disorder commonly produces tachycardia and a thready pulse. Its cardinal sign, however, is Kussmaul’s respirations—abnormally rapid, deep breathing. Other signs and symptoms of ketoacidosis include fruity breath odor, orthostatic hypotension, generalized weakness, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. The patient’s LOC may vary from lethargy to coma.

♦ Febrile illness. Fever can cause tachycardia. Related findings reflect the specific disorder.

♦ Heart failure. Especially common in leftsided heart failure, tachycardia may be accompanied by a ventricular gallop, fatigue, dyspnea (exertional and paroxysmal nocturnal), orthopnea, and leg edema. Eventually, the patient develops widespread signs and symptoms, such as palpitations, narrowed pulse pressure, hypotension, tachypnea, crackles, dependent edema, weight gain, slowed mental response, diaphoresis, pallor and, possibly, oliguria. Late signs include hemoptysis, cyanosis, marked hepatomegaly, and pitting edema.

♦ Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic nonketotic syndrome. A rapidly deteriorating LOC is commonly accompanied by tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnea, seizures, oliguria, and severe dehydration marked by poor skin turgor and dry mucous membranes.

♦ Hypertensive crisis. A life-threatening hypertensive crisis is characterized by tachycardia, tachypnea, diastolic blood pressure that exceeds 120 mm Hg, and systolic blood pressure that may exceed 200 mm Hg. Typically, the patient develops pulmonary edema with jugular vein distention, dyspnea, and pink, frothy sputum. Related findings include chest pain, severe headache, drowsiness, confusion, anxiety, tinnitus, epistaxis, muscle twitching, seizures, nausea and vomiting and, possibly, focal neurologic signs such as paresthesia.

♦ Hypoglycemia. A common sign of hypoglycemia, tachycardia is accompanied by hypothermia, nervousness, trembling, fatigue, malaise, weakness, headache, hunger, nausea, diaphoresis, and moist, clammy skin. Central nervous system effects include blurred or double vision, motor weakness, hemiplegia, seizures, and decreased LOC.

♦ Hyponatremia. Tachycardia is a rare effect of this electrolyte imbalance. Other findings include orthostatic hypotension, headache, muscle twitching and weakness, fatigue, oliguria or anuria, poor skin turgor, thirst, irritability, seizures, nausea and vomiting, and decreased LOC that may progress to coma. Severe hyponatremia may cause cyanosis and signs of vasomotor collapse such as thready pulse.

♦ Hypovolemia. Tachycardia may occur with this disorder along with hypotension, decreased skin turgor, sunken eyeballs, thirst, syncope, and dry skin and tongue.

♦ Hypovolemic shock. Mild tachycardia, an early sign of life-threatening hypovolemic shock, may be accompanied by tachypnea, restlessness, thirst, and pale, cool skin. As shock progresses, the patient’s skin becomes clammy and his pulse, increasingly rapid and thready. He may also develop hypotension, narrowed pulse pressure, oliguria, subnormal body temperature, and decreased LOC.

♦ Hypoxemia. Tachycardia may be accompanied by tachypnea, dyspnea, cyanosis, confusion, syncope, and incoordination.

♦ Myocardial infarction (MI). A life-threatening MI may cause tachycardia or bradycardia. Its classic symptom, however, is crushing substernal chest pain that may radiate to the left arm, jaw, neck, or shoulder. Auscultation may reveal an atrial gallop, a new murmur, and crackles. Other signs and symptoms include dyspnea, diaphoresis, nausea and vomiting, anxiety, restlessness, increased or decreased blood pressure, and pale, clammy skin.

♦ Neurogenic shock. Tachycardia or bradycardia may accompany tachypnea, apprehension, oliguria, variable body temperature, decreased LOC, and warm, dry skin.

♦ Orthostatic hypotension. Tachycardia accompanies the characteristic signs and symptoms of this condition, which include dizziness, syncope, pallor, blurred vision, diaphoresis, and nausea.

♦ Pheochromocytoma. Characterized by sustained or paroxysmal hypertension, this rare tumor may also cause tachycardia and palpitations. Other findings include headache, chest and abdominal pain, diaphoresis, paresthesia, tremors, nausea and vomiting, insomnia, extreme anxiety (possibly even panic), and pale or flushed, warm skin.

♦ Pneumothorax. Life-threatening pneumothorax causes tachycardia and other signs and symptoms of distress, such as severe dyspnea

and chest pain, tachypnea, and cyanosis. Related findings include dry cough, subcutaneous crepitation, absent or decreased breath sounds, cessation of normal chest movement on the affected side, and decreased vocal fremitus.

and chest pain, tachypnea, and cyanosis. Related findings include dry cough, subcutaneous crepitation, absent or decreased breath sounds, cessation of normal chest movement on the affected side, and decreased vocal fremitus.

Normal pediatric vital signs

This chart lists the normal resting respiratory rate, blood pressure, and pulse rate for girls and boys up to age 16.

Vital signs | Neonate | 2 years | 4 years | 6 years | 8 years | 10 years | 12 years | 14 years | 16 years |

Respiratory rate (breaths/minute) | |||||||||

Girls | 28 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 18 | 16 | |

Boys | 30 | 28 | 25 | 24 | 22 | 23 | 20 | 16 | 16 |

Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||||||

Girls | — | 98/60 | 98/60 | 98/64 | 104/68 | 110/72 | 114/74 | 118/76 | 120/78 |

Boys | — | 96/60 | 98/60 | 98/62 | 102/68 | 110/72 | 112/74 | 120/76 | 124/78 |

Pulse rate (beats/minute) | |||||||||

Girls | 130 | 110 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 85 | 80 |

Boys | 130 | 110 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 90 | 85 | 80 | 75 |

♦ Pulmonary embolism. In this disorder, tachycardia is usually preceded by sudden dyspnea, angina, or pleuritic chest pain. Common associated signs and symptoms include weak peripheral pulses, cyanosis, tachypnea, low-grade fever, restlessness, diaphoresis, and a dry cough or a cough producing blood-tinged sputum.

♦ Septic shock. Initially, septic shock produces chills, sudden fever, tachycardia, tachypnea and, possibly, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The patient’s skin is flushed, warm, and dry; his blood pressure is normal or slightly decreased. Eventually, he may display anxiety; restlessness; thirst; oliguria or anuria; cool, clammy, cyanotic skin; rapid, thready pulse; and severe hypotension. His LOC may decrease progressively, perhaps culminating in a coma.

♦ Thyrotoxicosis. Tachycardia is a classic feature of this thyroid disorder. Others include an enlarged thyroid gland, nervousness, heat intolerance, weight loss despite increased appetite, diaphoresis, diarrhea, tremors, palpitations, and sometimes exophthalmos.

Because thyrotoxicosis affects virtually every body system, its associated features are diverse and numerous. Some examples include full and bounding pulse, widened pulse pressure, dyspnea, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, altered bowel habits, hepatomegaly, and muscle weakness, fatigue, and atrophy. The patient’s skin is smooth, warm, and flushed; his hair is fine and soft and may gray prematurely or fall out. The female patient may have a reduced libido and oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea; the male patient may exhibit a reduced libido and gynecomastia.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Diagnostic tests. Cardiac catheterization and electrophysiologic studies may induce transient tachycardia.

♦ Drugs and alcohol. Various drugs affect the nervous system, circulatory system, or heart muscle, resulting in tachycardia. Examples of these include sympathomimetics; phenothiazines; anticholinergics such as atropine; thyroid drugs; vasodilators, such as hydralazine and nifedipine; acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as captopril; nitrates such as nitroglycerin; alpha-adrenergic blockers such as phentolamine; and beta-adrenergic bronchodilators such as albuterol. Excessive caffeine intake and alcohol intoxication may also cause tachycardia.

♦ Surgery and pacemakers. Cardiac surgery and pacemaker malfunction or wire irritation may cause tachycardia.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Continue to monitor the patient closely. Explain ordered diagnostic tests, such as a thyroid panel,

electrolyte and hemoglobin levels, hematocrit, pulmonary function studies, and 12-lead ECG. If appropriate, prepare him for an ambulatory ECG.

electrolyte and hemoglobin levels, hematocrit, pulmonary function studies, and 12-lead ECG. If appropriate, prepare him for an ambulatory ECG.

Teach the patient that tachycardia may recur. Explain that an antiarrhythmic and an internal defibrillator or ablation therapy may be indicated for symptomatic tachycardia.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

When assessing a child for tachycardia, be aware that normal heart rates for children are higher than those for adults. (See Normal pediatric vital signs.) Many of the adult causes described above may also cause tachycardia in children.

Tachypnea

A common sign of cardiopulmonary disorders, tachypnea is an abnormally fast respiratory rate—20 or more breaths/minute. Tachypnea may reflect the need to increase minute volume —the amount of air breathed each minute. Under these circumstances, it may be accompanied by an increase in tidal volume—the volume of air inhaled or exhaled per breath—resulting in hyperventilation. Tachypnea, however, may also reflect stiff lungs or overloaded ventilatory muscles, in which case tidal volume may actually be reduced.

Tachypnea may result from reduced arterial oxygen tension or arterial oxygen content, decreased perfusion, or increased oxygen demand. Increased oxygen demand may result from fever, exertion, anxiety, or pain. It may also occur as a compensatory response to metabolic acidosis or may result from pulmonary irritation, stretch receptor stimulation, or a neurologic disorder that upsets medullary respiratory control. Generally, the respiratory rate increases by 4 breaths/minute for every 1° F (0.5° C) increase in body temperature.

If you detect tachypnea, quickly evaluate the patient’s cardiopulmonary status; obtain vital signs including oxygen saturation; and check for cyanosis, chest pain, dyspnea, tachycardia, and hypotension. If the patient has paradoxical chest movement, suspect flail chest and immediately splint his chest with your hands or with sandbags. Then administer supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula or face mask and, if possible, place the patient in semi-Fowler’s position to help ease his breathing. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary if respiratory failure occurs. Also, insert an I.V. catheter for fluid and drug administration and begin cardiac monitoring.

If you detect tachypnea, quickly evaluate the patient’s cardiopulmonary status; obtain vital signs including oxygen saturation; and check for cyanosis, chest pain, dyspnea, tachycardia, and hypotension. If the patient has paradoxical chest movement, suspect flail chest and immediately splint his chest with your hands or with sandbags. Then administer supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula or face mask and, if possible, place the patient in semi-Fowler’s position to help ease his breathing. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary if respiratory failure occurs. Also, insert an I.V. catheter for fluid and drug administration and begin cardiac monitoring.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient’s condition permits, obtain a medical history. Find out when the tachypnea began. Did it follow activity? Has he had it before? Does the patient have a history of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or any other pulmonary or cardiac conditions? Then have him describe associated signs and symptoms, such as diaphoresis, chest pain, and recent weight loss. Is he anxious about anything or does he have a history of anxiety attacks? Note whether he takes any drugs for pain relief. If so, how effective are they?

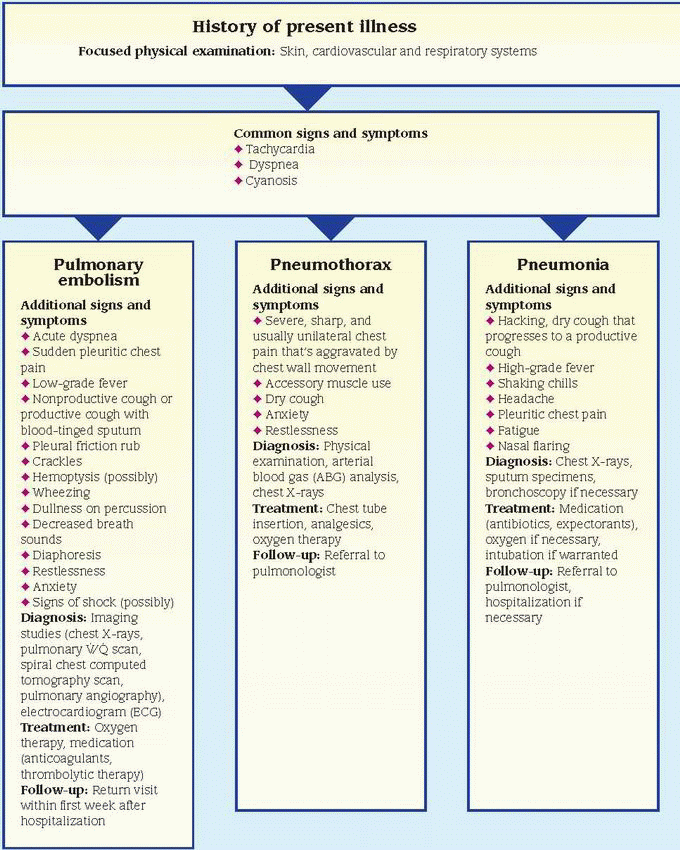

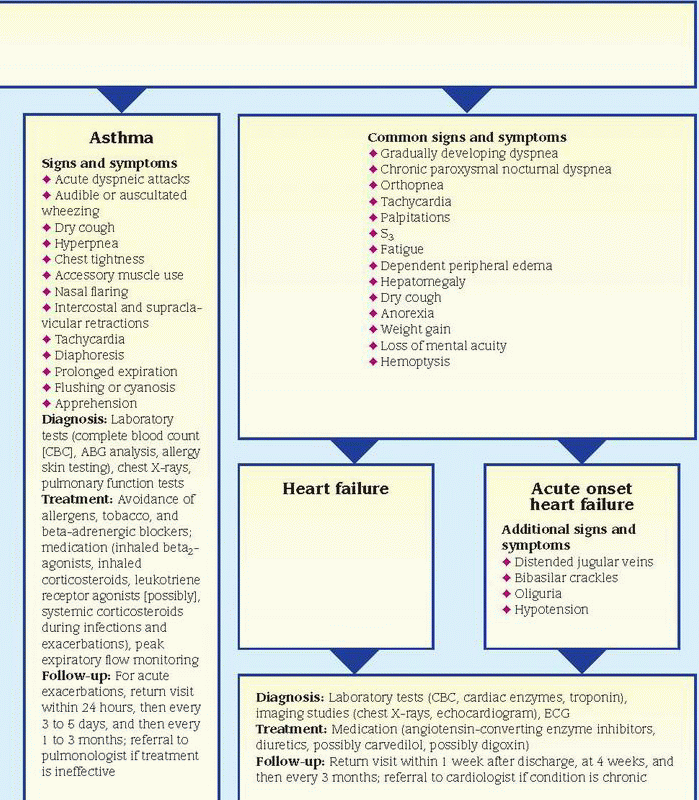

Begin the physical examination by taking the patient’s vital signs, including oxygen saturation, if you haven’t already done so, and observing his overall behavior. (See Differential diagnosis: Tachypnea, pages 648 and 649.) Does he seem restless, confused, or fatigued? Then auscultate the chest for abnormal heart and breath sounds. If the patient has a productive cough, record the color, amount, and consistency of sputum. Finally, check for jugular vein distention, and examine the skin for pallor, cyanosis, edema, and warmth or coolness.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Tachypnea and apprehension may be the earliest features of this life-threatening disorder. Tachypnea gradually worsens as fluid accumulates in the patient’s lungs, causing them to stiffen. It’s accompanied by accessory muscle use, grunting expirations, suprasternal and intercostal retractions, crackles, and rhonchi. Eventually, ARDS produces hypoxemia, resulting in tachycardia, dyspnea, cyanosis, respiratory failure, and shock.

♦ Alcohol withdrawal syndrome. A late sign in the acute phase of this syndrome, tachypnea typically accompanies anorexia, insomnia, tachycardia, fever, and diaphoresis. The patient may also experience anxiety, irritability, and bizarre visual or tactile hallucinations.

♦ Anaphylactic shock. In this life-threatening type of shock, tachypnea develops within minutes after exposure to an allergen, such as penicillin or insect venom. Accompanying signs and symptoms include anxiety, pounding headache, skin flushing, intense pruritus and, possibly, diffuse urticaria. The patient may exhibit widespread edema of the eyelids, lips, tongue, hands, feet, and genitalia. Other findings include cool, clammy skin; rapid, thready pulse; cough; dyspnea; stridor; and change or loss of voice associated with laryngeal edema.

♦ Anemia. Tachypnea may occur in this disorder, depending on the duration and severity of anemia. Associated signs and symptoms include fatigue, pallor, dyspnea, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, bounding pulse, an atrial gallop, and a systolic bruit over the carotid arteries.

♦ Anxiety. Tachypnea may occur during highanxiety states because of the “fight-or-flight” response. Associated signs and symptoms include tachycardia, restlessness, chest pain, nausea, and light-headedness, all of which dissipate as the anxiety state resolves.

♦ Aspiration of a foreign body. A life-threatening upper airway obstruction may result from aspiration of a foreign body. In a partial obstruction, the patient abruptly develops a paroxysmal dry cough with rapid, shallow respirations. Other signs and symptoms include dyspnea, gagging or choking, intercostal retractions, nasal flaring, cyanosis, decreased or absent breath sounds, hoarseness, and stridor or coarse wheezing. Typically, the patient appears frightened and distressed. A complete obstruction may rapidly cause asphyxia and death.

♦ Asthma. Tachypnea is common in lifethreatening asthma exacerbations, which commonly occur at night. These exacerbations usually begin with mild wheezing and a dry cough that progresses to mucus expectoration. Eventually, the patient becomes apprehensive and develops prolonged expirations, intercostal and supraclavicular retractions on inspiration, accessory muscle use, severe audible wheezing, rhonchi, flaring nostrils, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and flushing or cyanosis.

♦ Bronchiectasis. Although this disorder may produce tachypnea, its classic sign is a chronic productive cough that produces copious amounts of mucopurulent, foul-smelling sputum and, occasionally, hemoptysis. Related findings include coarse crackles on inspiration, exertional dyspnea, rhonchi, and halitosis. The patient may also exhibit fever, malaise, weight loss, fatigue, and weakness. Clubbing is a common late sign.

♦ Bronchitis (chronic). Mild tachypnea may occur in this form of COPD, but it isn’t typically a characteristic sign. Chronic bronchitis usually begins with a dry, hacking cough, which later produces copious amounts of sputum. Other characteristic findings include dyspnea, prolonged expirations, wheezing, scattered rhonchi, accessory muscle use, and cyanosis. Clubbing and barrel chest are late signs.

♦ Cardiac arrhythmias. Depending on the patient’s heart rate, tachypnea may occur along with hypotension, dizziness, palpitations, weakness, and fatigue. The patient’s level of consciousness (LOC) may be decreased.

♦ Cardiac tamponade. In life-threatening cardiac tamponade, tachypnea may accompany tachycardia, dyspnea, and paradoxical pulse. Related findings include muffled heart sounds, pericardial friction rub, chest pain, hypotension, narrowed pulse pressure, and hepatomegaly. The patient is noticeably anxious and restless. His skin is clammy and cyanotic, and his jugular veins are distended.

♦ Cardiogenic shock. Although many signs of cardiogenic shock appear in other types of shock, they’re usually more severe in this type. Besides tachypnea, the patient commonly displays cold, pale, clammy, cyanotic skin; hypotension; tachycardia; narrowed pulse pressure; a ventricular gallop; oliguria; decreased LOC; and jugular vein distention.

♦ Emphysema. This form of COPD commonly produces tachypnea accompanied by exertional dyspnea. It may also cause anorexia, malaise, peripheral cyanosis, pursed-lip breathing, accessory muscle use, and a chronic productive cough. Percussion yields a hyperresonant tone;

auscultation reveals wheezing, crackles, and diminished breath sounds. Clubbing and barrel chest are late signs.

auscultation reveals wheezing, crackles, and diminished breath sounds. Clubbing and barrel chest are late signs.

♦ Febrile illness. Fever can cause tachypnea, tachycardia, and other signs.

♦ Flail chest. Tachypnea usually appears early in this life-threatening disorder. Other findings include paradoxical chest wall movement, rib bruises and palpable fractures, localized chest pain, hypotension, and diminished breath sounds. The patient may also develop signs of respiratory distress, such as dyspnea and accessory muscle use.

♦ Head trauma. When trauma affects the brain stem, the patient may display central neurogenic hyperventilation, a form of tachypnea marked by rapid, even, and deep respirations. The tachypnea may be accompanied by other signs of life-threatening neurogenic dysfunction, such as coma, unequal and nonreactive pupils, seizures, hemiplegia, flaccidity, and hypoactive or absent deep tendon reflexes.

♦ Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic nonketotic syndrome. Rapidly deteriorating LOC occurs along with tachypnea, tachycardia, hypotension, seizures, oliguria, and signs of dehydration.

♦ Hypovolemic shock. An early sign of lifethreatening hypovolemic shock, tachypnea is accompanied by cool, pale skin; restlessness; thirst; and mild tachycardia. As shock progresses, the patient develops clammy skin and an increasingly rapid and thready pulse. Other findings include hypotension, narrowed pulse pressure, oliguria, subnormal body temperature, and decreased LOC.

♦ Hypoxia. Lack of oxygen from any cause increases the rate (and often the depth) of breathing. Associated symptoms are related to the cause of the hypoxia.

♦ Interstitial fibrosis. In this disorder, tachypnea develops gradually and may become severe. Associated features include exertional dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, a paroxysmal dry cough, crackles, late inspiratory wheezing, cyanosis, fatigue, and weight loss. Clubbing is a late sign.

♦ Lung abscess. In this type of abscess, tachypnea is usually paired with dyspnea and accentuated by fever. However, the chief sign is a productive cough with copious amounts of purulent, foul-smelling, usually bloody sputum. Other findings include chest pain, halitosis, diaphoresis, chills, fatigue, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, and clubbing.

♦ Lung, pleural, or mediastinal tumor. These types of tumors may cause tachypnea along with exertional dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, and pleuritic chest pain. Other effects include anorexia, weight loss, and fatigue.

♦ Mesothelioma (malignant). Commonly related to asbestos exposure, this pleural mass initially produces tachypnea and dyspnea on mild exertion. Other classic symptoms are persistent dull chest pain and aching shoulder pain that progresses to arm weakness and paresthesia. Later signs and symptoms include a cough, insomnia associated with pain, clubbing, and dullness over the malignant mesothelioma.

♦ Neurogenic shock. Tachypnea is characteristic in this life-threatening type of shock. It’s commonly accompanied by apprehension, bradycardia or tachycardia, oliguria, fluctuating body temperature, and decreased LOC that may progress to coma. The patient’s skin is warm, dry, and perhaps flushed. He may experience nausea and vomiting.

♦ Plague. The onset of the pneumonic form of this virulent bacterial infection is usually sudden and marked by chills, fever, headache, and myalgia. Pulmonary signs and symptoms include tachypnea, a productive cough, chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis, increasing respiratory distress, and cardiopulmonary insufficiency. The pneumonic form may be contracted by inhaling respiratory droplets from an infected person. It could also be contracted from aerosolization and inhalation of the organism in biological warfare.

♦ Pneumonia (bacterial). A common sign in this infection, tachypnea is usually preceded by a painful, hacking, dry cough that rapidly becomes productive. Other signs and symptoms quickly follow, including high fever, shaking chills, headache, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, tachycardia, grunting respirations, nasal flaring, and cyanosis. Auscultation reveals diminished breath sounds and fine crackles; percussion yields a dull tone.

♦ Pneumothorax. Tachypnea, a common sign of life-threatening pneumothorax, is typically accompanied by severe, sharp, and commonly unilateral chest pain that’s aggravated by chest movement. Associated signs and symptoms include dyspnea, tachycardia, accessory muscle use, asymmetrical chest expansion, a dry cough, cyanosis, anxiety, and restlessness. Examination of the affected lung reveals hyperresonance or tympany, subcutaneous crepitation, decreased vocal fremitus, and diminished or absent breath sounds. The patient with tension pneumothorax also develops a deviated trachea.

♦ Pulmonary edema. An early sign of this lifethreatening disorder, tachypnea is accompanied by exertional dyspnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and, later, orthopnea. Other features include a dry cough, crackles, tachycardia, and a ventricular gallop. In severe pulmonary edema, respirations become increasingly rapid and labored, tachycardia worsens, crackles become more diffuse, and. the cough produces frothy, bloody sputum. Signs of shock—such as hypotension, thready pulse, and cold, clammy skin—may also occur.

♦ Pulmonary embolism (acute). In pulmonary embolism, tachypnea occurs suddenly and is usually accompanied by dyspnea. The patient may complain of angina or pleuritic chest pain. Other characteristic findings include tachycardia, a dry or productive cough with blood-tinged sputum, low-grade fever, restlessness, and diaphoresis. Less common signs include massive hemoptysis, chest splinting, leg edema, and—with a large embolus—jugular vein distention and syncope. Other findings include pleural friction rub, crackles, diffuse wheezing, dullness on percussion, diminished breath sounds, and signs of shock, such as hypotension and a weak, rapid pulse.

♦ Pulmonary hypertension (primary). In this rare disorder, tachypnea is usually a late sign that’s accompanied by exertional dyspnea, general fatigue, weakness, and episodes of syncope. The patient may complain of angina on exertion, which may radiate to the neck. Other effects include a cough, hemoptysis, and hoarseness.

♦ Septic shock. Early in septic shock, the patient usually experiences tachypnea; sudden fever; chills; flushed, warm, yet dry skin; and possibly nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. He may also develop tachycardia and normal or slightly decreased blood pressure. As this lifethreatening type of shock progresses, the patient may display anxiety; restlessness; decreased LOC; hypotension; cool, clammy, and cyanotic skin; rapid, thready pulse; thirst; and oliguria that may progress to anuria.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Salicylates. Tachypnea may result from an overdose of these drugs.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs closely. Be sure to keep suction and emergency equipment nearby. Prepare to intubate the patient and to provide mechanical ventilation if necessary. Prepare the patient for diagnostic studies, such as arterial blood gas analysis, blood cultures, chest X-rays, pulmonary function tests, and an electrocardiogram.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

When assessing a child for tachypnea, be aware that the normal respiratory rate varies with the child’s age. (See Normal pediatric vital signs, pages 646 and 647.) If you detect tachypnea, first rule out the causes listed above. Then consider these pediatric causes: congenital heart defects, meningitis, metabolic acidosis, and cystic fibrosis. Keep in mind, however, that hunger and anxiety may also cause tachypnea.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Tachypnea may have a variety of causes in elderly patients, such as pneumonia, heart failure, COPD, anxiety, or failure to take cardiac and respiratory medications appropriately; mild increases in respiratory rate may be unnoticed.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Reassure the patient that slight increases in respiratory rate may be normal.

Taste abnormalities

There are several types of taste impairment. Ageusia is complete loss of taste; hypogeusia, partial loss of taste; and dysgeusia, a distorted sense of taste. In cacogeusia, food may taste unpleasant or even revolting.

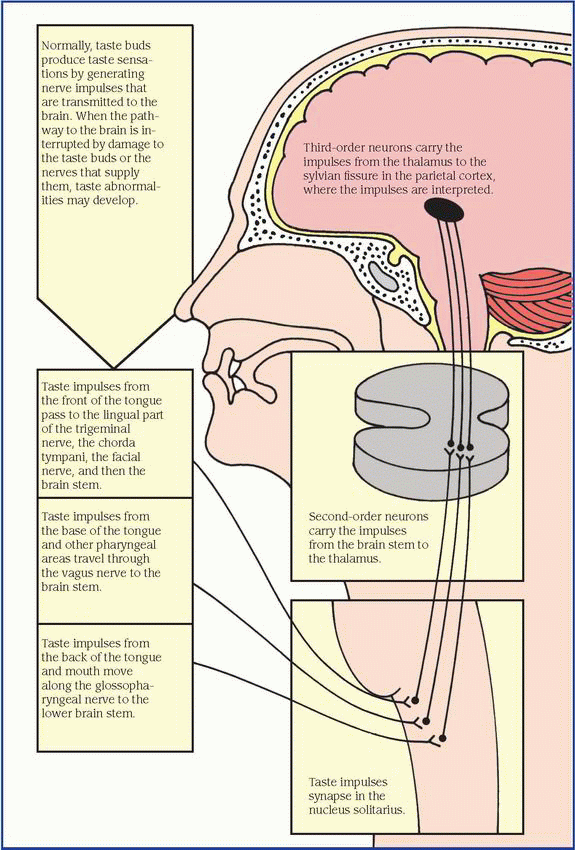

The sensory receptors for taste are the taste buds, which are concentrated over the tongue’s surface and scattered over the palate, pharynx, and larynx. These buds can differentiate among sweet, salty, sour, and bitter stimuli. More complex flavors are perceived by taste and olfactory receptors together. In fact, much of what people call taste is actually smell; food odors typically stimulate the olfactory system more strongly than food tastes stimulate the taste buds.

Any factor that interrupts transmission of taste stimuli to the brain may cause taste abnormalities. (See Tracing taste pathways to the brain.) Such factors include trauma, infection, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, neurologic and oral disorders, and drug effects. In addition, because tastes are most accurately perceived in a fluid medium, mouth dryness may interfere with taste.

Two major nonpathologic causes of impaired taste are aging, which normally reduces the number of taste buds, and heavy smoking (especially pipe smoking), which dries the tongue.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

After noting the patient’s age, find out when his taste abnormality began and then search for possible causes. Does the patient have a history of oral or other disorders? Has he recently had the flu or suffered head trauma? Does he smoke? Is he receiving radiation treatments? Is he currently taking any medications?

Next, thoroughly evaluate the patient’s sense of taste. Gently withdraw his tongue slightly with a gauze sponge. Then use a moistened applicator to place a few crystals of salt or sugar on one side of the tongue. Ask the patient to identify the taste sensation while his tongue is protruded. Repeat the test on the other side of the tongue. To test bitter taste sensation, apply a tiny amount of quinine to the base of the tongue. To test sour taste sensation, apply a tiny amount of dilute vinegar on the base of the tongue. Inspect the oral cavity for lesions, sores, and mucosal abnormalities. Observe the taste buds for any obvious abnormalities.

Finally, evaluate the patient’s sense of smell. Pinch one nostril and ask the patient to close his eyes and sniff through the open nostril to identify nonirritating odors, such as coffee, lime, and wintergreen. Repeat the test on the other nostril.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Basilar skull fracture. If the first cranial nerve is involved in this traumatic injury, the patient usually can’t detect aromatic flavors but can still correctly identify sweet, salty, sour, and bitter stimuli. Other findings include epistaxis, rhinorrhea, otorrhea, Battle’s sign, raccoon eyes, headache, nausea and vomiting, hearing and vision loss, and a decreased level of consciousness.

♦ Bell’s palsy. Taste loss involving the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is common in this disorder, as is hemifacial muscle weakness or paralysis. The affected side of the patient’s face sags and is masklike. Associated signs include drooling and tearing, diminished or absent corneal reflex, and difficulty blinking the affected eye.

♦ Common cold. Although impaired taste sense is a common complaint, it’s usually secondary to loss of smell. Other common features include rhinorrhea with nasal congestion, sore throat, headache, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, malaise, and a dry, hacking cough.

♦ Geographic tongue. Taste abnormalities occur along with many areas of loss and regrowth of filiform papillae. These areas are continually changing and produce a maplike appearance with denuded red patches surrounded by thick white borders.

♦ Influenza. After this viral infection, the patient may have hypogeusia, dysgeusia, or both. Typically, he also reports an impaired sense of smell.

♦ Oral cancer. About half of all oral tumors involve the tongue, especially the posterior portion and the lateral borders. These tumors may destroy or damage taste buds, resulting in impaired taste. The patient also has difficulty chewing and speaking and may develop halitosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree