FIGURE 45-1 Picture of a typical implantable loop recorder. Note the size relative to the finger. (Image used with permission of Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota.)

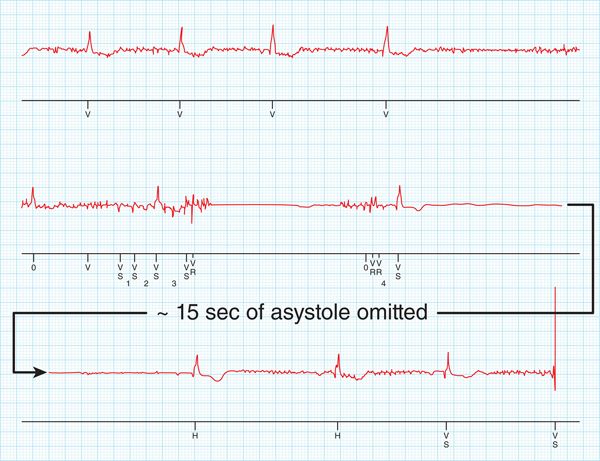

FIGURE 45-2 Ventricular bigeminy associated with “dizzy” spell, presumably due to a slow net heart rate.

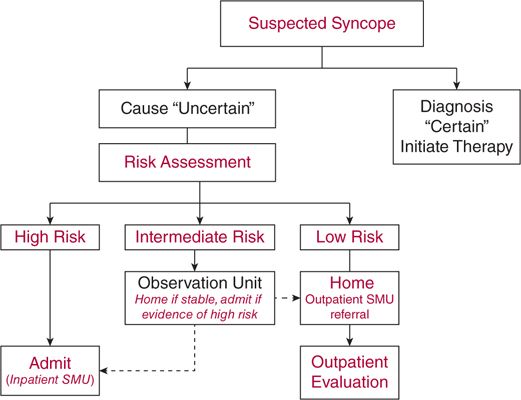

Approximately 6 weeks later, the patient slumped to the floor while sweeping out his garage. His wife called 911, and he was brought to the emergency department. His ILR was interrogated, and a diagnosis of symptomatic bradycardia was established (Figure 45-3). Based on this finding a pacemaker was indicated. During the subsequent year he has not suffered any further syncope episodes. However, ablation of ventricular ectopy has been scheduled given his persistent ventricular bigeminy and “dizzy” spells.

FIGURE 45-3 Prolonged asystolic pause recorded by ILR in conjunction with the patient’s abrupt collapse.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Syncope (“faint”) is a brief, self-limited period (usually less than 1-2 minutes) in which loss of consciousness occurs a result of transient cerebral hypoperfusion. There are many possible causes. The percentage of patients who report having experienced a faint varies from 15% to 25% in Western countries.1,2 Syncope accounts for 1% of all visits to emergency departments or urgent care clinics in Europe and around 1% to 6% of such visits in the United States.1–3

CAUSES

Vasovagal and orthostatic faints are the most common forms of syncope across all age groups.1,4–6 In younger patients without any structural heart disease, neurally mediated reflex faints, particularly vasovagal syncope or situational faints (eg, postmicturition syncope, cough syncope), account for the vast majority. In older patients, carotid sinus syndrome (CSS) becomes of increasing importance and has been reported to account for up to 20% of syncope in this group.1,4 Older patients are also more likely to experience orthostatic syncope.4

Cardiac causes of syncope include structural heart disease (ie, coronary artery disease, valvular disease, cardiomyopathies, consequences of hypertension) and arrhythmias. Increased mortality risk is a concern in these patients1,5; however, the primary mortality “driver” is the severity of the underlying heart disease rather than the syncope itself.1 In the absence of overt structural disease, the possibility of a so-called channelopathy (eg, long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, catecholaminergic paroxysmal VT) should not be overlooked.1 In addition, occasionally premature coronary artery disease may trigger an arrhythmia in individuals who are seemingly healthy.

ESTABLISHING THE BASIS FOR SYNCOPE AND RISK STRATIFICATION

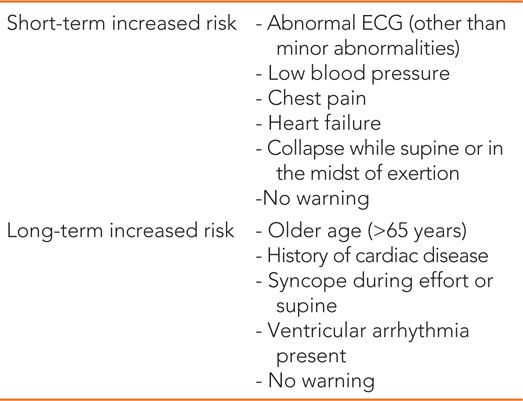

The urgency of establishing the basis of syncope is determined by assessment of the patient’s short-term and long-term potential morbidity and mortality risk. This “risk assessment” step has received considerable attention recently.1–6,11 Its importance relates in part to potential for sudden unexpected death in such patients, but also (and perhaps more commonly) to susceptibility for syncope to recur in affected individuals and result in falls with injury and economic and life-style disruption. Table 45-1 provides a list of clinical findings (derived from multiple reports) that trigger concern regarding high risk of early (<1 month) syncope recurrence.

TABLE 45-1 Clinical Observations Suggesting Increased Risk in Syncope/Collapse Patients

Longer-term risk of syncope recurrence (ie, <1 year) is more difficult to predict. However, a few studies have attempted to address this issue.1,6 Table 45-1 summarizes a number of clinical observations that should raise concern regarding increased risk of syncope recurrence over the next year.

DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGY AND SPECIFIC CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Figure 45-4 summarizes a basic strategy for the initial clinical evaluation and disposition of syncope/collapse patients. The initial evaluation requires a careful medical history (including accounts from witnesses) followed by risk assessment or risk stratification. The availability of a syncope clini or syncope management unit is of value in order to enhance efficiency of patient care by avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations and diminishing the number of “diagnostic” tests being ordered, while increasing diagnostic yield.

FIGURE 45-4 Management strategy for patients presenting to emergency departments or clinics with transient loss of consciousness and presumed syncope.

A preprepared history form may facilitate the recording of a complete story. The provider should try to obtain the answers for the following key questions as part of the history taking:

• Is loss of consciousness attributable to true syncope versus other causes of real or seemingly real loss of consciousness, including accidental falls?

• Is heart disease present?

• Are there important clinical features in the history that suggest the diagnosis? (eg, premonitory symptoms in vasovagal fainters)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree