Symptoms Related to the Ears, Nose, and Throat

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Common disorders of the upper respiratory tract are among the most frequent disorders dealt with by all health professionals. The runny or stuffy noses, earaches, and sore throats are universal afflictions dealt with by everyone. They may also be associated with a cough that is not the predominant symptom. Differential diagnosis of cough as the most significant symptom will be covered in more detail in the Chapter 8. These symptoms can occur alone or in combination, and carefully identifying the cause can allow prompt and effective treatment or referral to definitive care.

• RUNNY/STUFFY NOSE

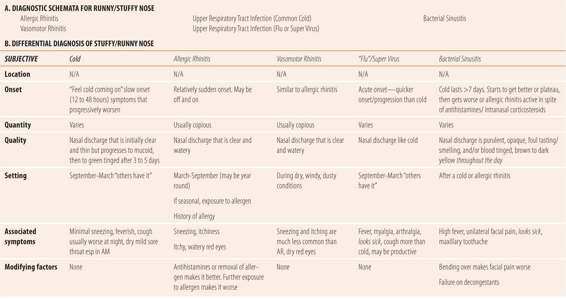

Two common viral infections, allergic rhinitis, vasomotor rhinitis, and bacterial sinusitis make up the most common among the vast number of diseases that present with the chief complaint of a runny or stuffy nose. Table 7.1 provides the diagnostic schemata and comparative presentations.

| TABLE 7.1 | Stuffy/Runny Nose |

Common Cold (Upper Respiratory Infection)

Caused by rhinoviruses or coronaviruses, the common cold represents over 60% of all disorders with nasal stuffiness or discharge as the primary complaint. Generally, the onset is slow with symptoms progressing over 12 to 36 hours and lasting 5 to 9 days. Nasal discharge is initially clear but progresses to mucoid and the amount varies over the course of the disease. Most patients will notice a green tinge to the mucous after 3 to 5 days, which is indicative of a viral not bacterial infection as previously thought. Sneezing is generally not a prominent feature. Patients may complain of a dry cough that is worse at night. There may also be a mild sore throat upon wakening in the morning. Both symptoms may be attributable to post-nasal drip. The sore throat often resolves after eating. Examination of the nose reveals pink to red (normal color), but swollen turbinates with a mucoid discharge. Most patients present with either no fever or only a low-grade fever.

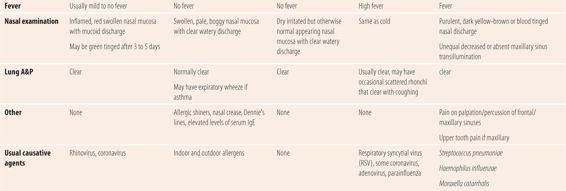

Many patients will present incorrectly saying they have “the flu”. They probably do not have true influenza, but a more symptomatic form of the common cold or upper respiratory infection (URI). True influenza is a much more severe seasonal respiratory disorder in which runny nose, sore throat, and earache are not the predominant symptoms. (See Table 7.2 for differences between URI and influenza.) This “super virus” is caused by respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, or coronaviruses and tends to present with a more acute and rapid onset, often with fever, myalgias, and arthralgias. Patients with these super virus infections tend to look sick. The cough may be productive and the sore throat may be more bothersome. Physical findings other than fever are similar to those of rhinovirus infections. This form of URI generally lasts several days longer than the common cold. The mucoid discharge also develops a green tinge over time. It is still a viral infection, and antibiotics have no effect on duration or severity of the illness. Like the common cold, it occurs predominantly in the late fall and winter months.

| TABLE 7.2 | Cold Versus Flu Symptoms |

Allergic Rhinitis

The signs and symptoms of allergic rhinitis (AR) are significantly different than with viral URIs. The nasal discharge is copious, clear, and watery. Sneezing is a prominent feature. Its onset is usually sudden, and it can wax and wane, depending on the exposure to the airborne allergen. Nasal congestion can be the most troublesome symptom. The nose and the palate of the throat may itch. Many patients will have red, itchy, and watery eyes (allergic conjunctivitis). Because the cause is often outdoor airborne allergens such as pollen, it occurs in most parts of the country beginning in spring and lasting until fall. Some patients have allergy symptoms year round, due to moderate winters, or they may have an allergy to one or more indoor allergens, such as house dust mites, cockroaches, or indoor molds. Many people are aware they have allergies or may have a history or a family of allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and/or asthma. Avoiding exposure to the allergen, if known, as well as taking an antihistamine will decrease the frequency and severity of the symptoms. Patients are afebrile, and on examination they generally have pale, boggy, swollen nasal turbinates with a clear watery discharge. In addition, if the allergic rhinitis is chronic or perennial they may have allergic shiners, dark areas on their face below the eyes, near the nose due to the vasodilation associated with the chronic nasal congestion, a nasal crease, and Dennie’s lines. In patients with allergic rhinitis, a careful history regarding asthma and its symptoms, including early morning cough or a family history of asthma, should be elicited since a significant percentage of patients have concurrent asthma. Auscultation of the lungs should be performed to determine whether or not the expiratory wheezing typical of asthma is present.

Vasomotor Rhinitis

In parts of the country where it can be dry and windy, patients appearing to have allergic rhinitis symptoms may have vasomotor rhinitis. Symptoms are similar to allergic rhinitis in terms of the nasal discharge, and can present with red irritated eyes without the discharge. Vasomotor rhinitis is an irritant rhinitis, not an immune-mediated disease such as allergic rhinitis. The primary way to distinguish it is by examining the nasal mucosa. In vasomotor rhinitis, the nasal mucosa is dry but the normal pink-red color, not pale. Also, patients will fail to respond to antihistamines and do not have allergic shiners, and other physical findings of AR.

Acute Bacterial Sinusitis

Bacterial sinusitis is uncommon. In patients with nasal symptoms for 14 or more days, only 0.2% to 2% of patients have bacterial sinusitis. Bacterial sinusitis is not directly communicable: that is, one does not catch it as one does the common cold. Rather, it is usually caused by bacteria that colonize the upper respiratory tract, most commonly Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. The bacterial infectious disease is a secondary event, which invariably follows an inciting event, usually either a viral URI or active allergic rhinitis. The typical clinical course is that the patient has a viral URI or an exacerbation of allergic rhinitis. The manifestations of this primary event start to get better after a week, but then symptoms suddenly worsen. Patients may complain of a headache centered near one eye. The pain is often worsened by bending over, and there is a purulent (opaque, dark yellow, or brown) nasal discharge throughout the day. Patients should be asked about the color of the discharge during the afternoon or after they have been awake and ambulatory for at least 6 hours. This is because most patients have opaque, yellowish brown discharge in the morning due to evaporation of moisture during the night. However, if this persists throughout the day, it is more consistent with true bacterial sinusitis. In addition, the nasal discharge may be described as bad smelling or foul tasting. The presence of a toothache may be a manifestation of a maxillary sinus infection. Some patients notice impaired smell and taste. Infrequently, cough, usually nonproductive and which worsens at night, occurs with acute bacterial sinusitis. Another factor that favors bacterial infection is the failure of a decongestant. However, this must be interpreted with caution since most patients who use decongestants continually will quickly notice that they do not work as well as they did initially. This is due to the development of tachyphylaxis due to downregulation of adrenergic receptors with continuous exposure. This necessitates larger dosage and/or more frequent use to get the efficacy similar to the initial dose. Objectively, patients may present with pain on palpation or percussion of the maxillary and frontal sinuses. Remember to palpate gently first, and percuss only if there is no pain on palpation. Patients may also have unequal, decreased, or absent transillumination of the maxillary sinus. Patients usually are febrile, but in the absence of fever, check to see what the patient has taken in the last 4 to 6 hours. Analgesics such as acetaminophen and NSAIDs, given for pain, are also antipyretics and may mask the fever.

Summary

The key in diagnosis of causes of a runny, stuffy nose is to distinguish allergic rhinitis and bacterial sinusitis from viral URIs because the former two are the maladies for which there are effective treatments.

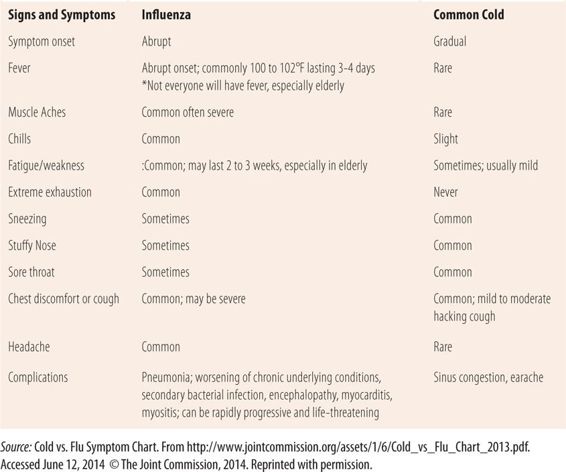

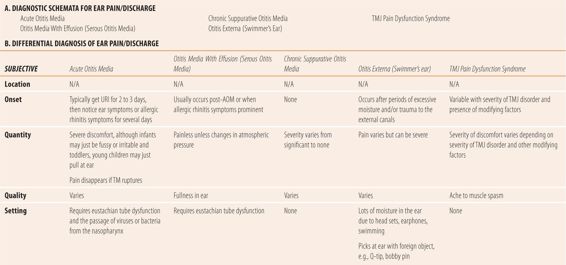

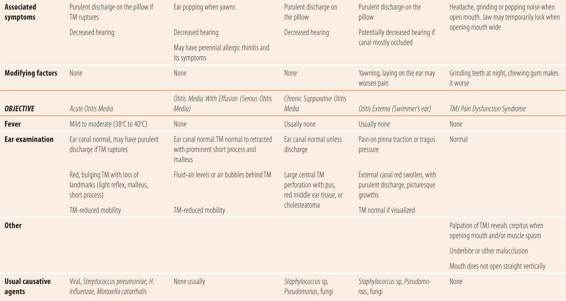

• EAR PAIN/DISCHARGE

There are multiple causes for ear pain or discomfort, purulent discharge from an ear, and even associated acute hearing loss including acute otitis media, serous otitis media (aka otitis media with effusion), otitis externa, chronic suppurative otitis media, and cerumen impaction. There are also some causes of ear pain that are not caused by ear problems. Examples of these include temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders (also called TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome and TMJ syndrome), dental disorders, and streptococcal pharyngitis. Table 7.3 provides the diagnostic schemata and the comparative presentations for the most common disorders related to the ear.

| TABLE 7.3 | Ear Pain/Discharge |

Acute Otitis Media

The development of middle ear infections requires the transit of colonizing bacteria or viruses from the nasopharynx or oropharynx, up into the eustachian tube followed by lack of normal patency or drainage from the tube. Several things are common causes of abnormal closure or dysfunction of the eustachian tube. These include any of the causes of swelling or enlargement of posterior pharyngeal lymphoid tissue, like a cold (viral URI) or upper respiratory manifestations of allergies. Roughly half are caused by respiratory viruses; the remaining are caused by the respiratory tract bacteria, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Acute otitis media (AOM) occurs mostly in children under 6 years of age who have relatively short straight eustachian tubes. By 6 years of age, the eustachian tube is considerably longer and is curved, making the retrograde transit of microorganisms more difficult. Bottle propping in infants and toddlers who are lying on their back promotes passage of the ingested fluid with bacteria into the middle ear. In most cases, the onset of AOM symptoms is preceded by a 2- to 3-day history of viral URI or allergic rhinitis. In children who have not yet developed significant verbal skills, the ear pain is manifested by pulling at the affected ear or generalized fussiness or irritability. AOM is usually accompanied by a fever and decreased hearing in the affected ear. The natural course of AOM leads to increasing pain and pressure, finally resulting in a pinpoint perforation in the tympanic membrane (TM) with immediate cessation of severe pain due to the release of pressure. Over two-thirds of the cases resolve spontaneously without sequelae. This is true of virtually all viral causes and many cases caused by Haemophilus and Moraxella. While the cases caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae are less likely to resolve spontaneously, many still do. In less than 1% of the cases due to more virulent organisms such as S. pneumoniae, the mastoid bone is invaded, causing mastoiditis.

Objectively, most patients have a fever. On otoscopic examination, the TM is usually red. If tympanometry or pneumatic otoscopy is done, the TM is nonmobile. It may be bulging, and a pinpoint perforation may be visible. Normal landmarks are not visible. There may be a purulent discharge coming from the pinpoint perforation, and/or it may be noticed on the floor of the external canal. If the TM ruptures during sleep, the discharge can stain the pillow and the patient awakens to find the ear pain much better or gone. Current guidelines recommend that for most children 2 or over, only analgesic/antipyretics be given for 48 hours. Almost 75% will resolve without antibiotic therapy. Even for those patients referred to a primary care provider for severe symptoms for antibiotic therapy (whether < 2 years old or not), OTC analgesics/antipyretic products are appropriate. However, follow-up visits are required to check for the potential development of otitis media with effusion.

Otitis Media With Effusion/Serous Otitis Media

The term otitis media with effusion (OME) more accurately reflects our knowledge of the inflammatory nature of the disease. Serous otitis media (SOM), an older but still frequently used term, reflected the belief (at the time) that there was only fluid behind the ear not caused by inflammation. It is now thought that there are two causes of OME: allergic rhinitis and post-AOM. In children who have had AOM, more than 60% will have some effusion remaining up to 8 weeks later. Like AOM, eustachian tube blockage/dysfunction is required for the development of OME. Usually OME resolves spontaneously without sequelae, but in some cases the inflammation creates bubbles of CO2 in the fluid, which diffuse out into the blood stream, creating a vacuum that pulls the TM back against the middle ear bones, causing them to touch each other. Untreated, this can eventually cause permanent hearing loss when the bones fuse. Generally, OME is painless unless there are changes in atmospheric pressure as occurs during takeoff and landing of an aircraft. Patients may notice a sensation of fullness, decreased hearing, and ear popping when yawning. Otoscopic examination reveals a nonmobile TM, possibly with the presence of an air fluid level or air bubbles behind the TM. The landmarks, particularly the malleus and its short process, become very prominent because the TM is retracted against the middle ear bones in more severe cases. The TM may be somewhat bluish in appearance. Treatment of severe OME with a retracted TM requires the placement of pressure equalization tubes (PE tubes) through the TM. The tubes function to equalize the pressure, relieving the retraction induced contact with the bones of the middle ear, while allowing the inflammation to run its course. OME does not require antibiotic therapy. The efficacy of decongestants or corticosteroids is controversial.

Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) differs considerably from AOM. First, it requires the presence of a large central perforation in the TM. The cause of this central perforation is unclear. Trauma, placement of PE tubes, high fever, and repeated episodes of AOM with perforation have all been identified as causes. Rather than respiratory tract bacteria, the pathogens come from the flora of the external canal with Staphylococcus species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa predominating as causative agents. Other gram-negative bacteria can also be involved. Bacteria migrate through the central perforation, often facilitated by water from swimming or showering. Once inside the middle ear, they infect tissue and with accompanying inflammation, cause a purulent discharge. If untreated, this process can destroy important middle ear tissue, and invade the mastoid and other bony structures of the cranium. In chronic cases, a whitish cyst made up of epithelial tissue called a cholesteatoma may form. This tissue can enlarge, become infected, and eventually destroy middle ear bones. The two major symptoms of CSOM are decreased hearing and a purulent discharge for >14 days. Pain is generally not a prominent feature except in more widespread disease. On otoscopic examination, there is a large central TM perforation with a purulent discharge. In long-standing disease, there may be a cholesteatoma seen as a whitish cyst in the middle ear. Patients with suspected CSOM should be referred to an otorhinolaryngologist, as soon as possible, for definitive treatment.

Otitis Externa (Swimmer’s Ear)

Otitis externa (OE) is an infection of the external ear canal. Trauma from cleaning ears with foreign objects, wearing earpieces chronically, and constant moisture from sweat (especially while wearing earphones), or frequent immersion of the head in water (swimming) are all predisposing factors. Common pathogens include normal external ear canal flora including Staphylococcus sp, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and multiple fungi. Patients generally have one or more predisposing factors and present with pain/discomfort and a purulent discharge. Hearing may or may not be affected depending on the amount of swelling and debris. Complete otoscopic examination may not be possible. However, to the extent that it is possible, usual findings include a red, swollen external canal with purulent material. With fungal infections, picturesque growths with colorful spores or hyphae may be seen. The TM is mobile on pneumatic ostoscopy, but swelling, debris, and especially pain in the external canal may prevent complete visualization of the TM. Since the canal is swollen and painful, the cardinal diagnostic finding is pain with a firm pull on the earlobe (pinna) or pressure on the tragus. Eliciting pain on pinna pull is generally diagnostic since patients with other ear disease will not experience any pain with this maneuver. In addition, there may be peri- or post-auricular lymphadenopathy. Finally, if you suspect OE, be careful during the otoscopic examination. That is gently pull the pinna and possibly use a small diameter disposable otoscope speculum.

Ear Pain With a Normal Otoscopic Examination

Occasionally, a patient complaining of ear pain will have a normal otoscopic examination. When that occurs, think of referred pain from a dental problem, pharyngitis, or TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome. Specific problems may include a tooth abscess or streptococcal pharyngitis. A normal otoscopic examination in this setting warrants a mouth and throat examination by applying pressure on each tooth with a tongue depressor to detect abscessed teeth. Also, palpation over the TMJ and observation of the mouth opening should be conducted.

TMJ Pain Dysfunction Syndrome

TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome can cause pain in the area of the ear due to muscle spasms caused by grinding the teeth (bruxism), or structural and/or functional abnormalities of the TMJ. Patients may complain of ear pain, headache, or tinnitus. These patients may admit to a grinding, clicking, popping, snapping sensation or noise when they open and close their mouth. Ask if they grind their teeth at night and how frequently they chew gum, as both are typical in TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome. A quick check for TMJ problems can be done when examining the peri- and post-auricular lymph nodes. Press gently against the TMJ (just in front of the ears) and have the patient open their mouth slowly. Any clicking, grinding, popping sensations palpated may indicate TMJ problems. Also, palpable muscle spasms may be felt over the joint, which is typical. Watch the opening of the mouth carefully. If it does not open smoothly straight up and down, there may be TMJ problems. Finally, check for dental malocclusions especially an underbite. Generally, patients with TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome will have multiple suspicious findings, e.g., an underbite, a history of chewing gum frequently, an irregular mouth opening, and the presence of grinding, clicking, popping over the TMJ on palpation. Patients suspected of TMJ problems should be initially referred to a dentist for further evaluation.

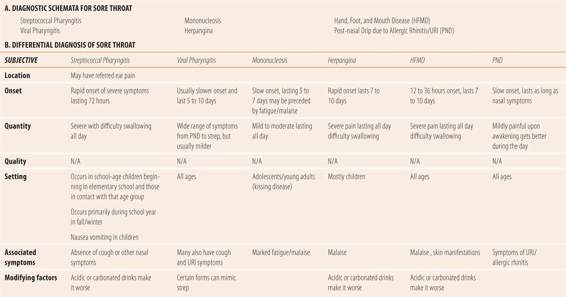

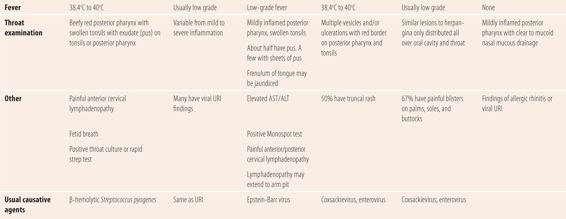

• SORE THROAT/HOARSENESS

There are multiple causes of sore throats, but most are due to either infections (bacterial or viral) or irritant/allergic disorders. The most common bacterial infectious cause of sore throat is Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A β-hemolytic strep or GABHS) also known as strep throat. Numerous other bacteria have been implicated as causes of sore throat, but are less common (including Fusobacterium necrophorum, Arcanobacterium haemolyticum, Group C and G streptococci, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, N. gonorrhoeae, and even Corynebacterium diphtheriae). There are many viral causes, but the most common are those associated with viral URIs, which create pharyngitis either directly or by post-nasal drip. Other viral causes of pharyngitis include influenza viruses, coxsackieviruses (including those that cause herpangina and hand, foot, and mouth disease), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is the cause of mononucleosis, and cytomegalovirus (CMV). Since primary HIV infections often cause a syndrome like mononucleosis, with pharyngitis as a common component, depending on their individual risk factors, patients should have this diagnosis considered. Another common cause of sore throat, usually by a post-nasal drip mechanism, is allergic rhinitis. Distinguishing between causes of hoarseness is also important. Viral laryngitis is a minor self-limiting disorder, whereas acute epiglottitis and carcinoma of the larynx can both be fatal if not diagnosed early and accurately. Table 7.4 provides the diagnostic schemata and comparative presentations of sore throat.

| TABLE 7.4 | Sore Throat |

Streptococcal Pharyngitis

Strep throat is caused by a Group A β-hemolytic strep (Streptococcus pyogenes). It represents between 10% and 30% of all patients reporting a sore throat as the primary or only symptom. It occurs most frequently in elementary school-age children (ages 5 to 11) and those in contact with them. Most cases occur during the school year, peaking during the winter months. Circumstances associated with crowding of people, like a closed classroom, facilitate transmission of the organism. Recently, due to the large number of children in organized daycare or preschool, the age of suspicion for strep throat is considerably lower than previously seen. Concern for an accurate diagnosis is based on the possibility of nonsuppurative (autoimmune) inflammatory sequelae, acute rheumatic fever, in untreated patients. Acute rheumatic fever occurs between 2 and 5 weeks after the sore throat and presents with fever, carditis, migratory polyarthritis, and/or chorea. The carditis can result in permanent valvular damage and risk for developing bacterial endocarditis. Due to careful attention to its diagnosis and prompt treatment, the incidence has been drastically reduced since the late 1940s to just one per 1 million population.

Subjectively, patients present with sudden onset of fever and severe sore throat, difficulty swallowing with pain worsened when swallowing acid liquids such as citrus juices and carbonated beverages. The pain is severe and constant throughout the day. Cough and nasal symptoms are uncommon. Malaise is common, but arthralgias and myalgias are not. Gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain may occur, but are more common in children. Generally, symptoms markedly improve by 72 hours after onset. Symptoms lasting longer than that should raise the suspicion of other causes such as viral pharyngitis and mononucleosis. A recent history of exposure to someone with a severe sore throat or diagnosed strep throat is common.

Objectively, examination of the throat and tonsils will reveal beefy red color, usually with purulent exudates and in many cases fetid (foul smelling) breath. Achieving complete visualization of the posterior pharynx and/or obtaining a culture or rapid strep test usually requires inducing the gag reflex with a tongue depressor. However, in a significant number of patients having them open their mouth wide, sticking their tongue out, and “panting like a dog” may preclude the need for a tongue depressor. Tonsillar tissue may be swollen. A marked fever (39°C to 40.5°C) is a significant feature. Painful anterior cervical adenopathy is typical. A small number of patients will have a skin rash comprised of fine red papules on the truck that spread to the extremities but not the palms and soles of the feet. Typically, it has a sandpaper-like feel and blanches upon pressure. This manifestation is called scarlet fever or scarlatina. The classic confirmation for diagnosis is considered to be the throat culture. However, due to the 48-hour delay in obtaining culture results and the need to start therapy as soon as possible, the Rapid Antigen Detection Test (RADT) for S. pyogenes is usually preferred. Results of these tests are available in minutes. Unfortunately, they have a relatively high rate of false-positive findings because as many as one-fourth of patients are carriers of β-hemolytic Streptococcus. There is also a significant number of false negatives, mostly a function of poor sampling technique. Therefore, practically speaking, the clinical diagnosis requires a combination of typical features plus bacteriologic confirmation to accurately make the diagnosis. More technically, to rule out the carrier state, a definitive diagnosis requires typical signs and symptoms, plus some confirmation of the presence of the organism in the pharynx by standard culture or an RADT, and a positive result of acute and convalescent serologic tests for GABHS (i.e., antistreptolysin O or ASO test). If one tonsillar pillar or the uvula is swollen and displaced and the patient has difficulty opening their mouth without pain, suspect the suppurative complication peritonsillar abscess, which requires immediate referral.

Viral Pharyngitis

Generally, viral pharyngitis presents with a wide range of symptoms and degrees of severity depending on the specific virus. Rhinovirus, adenovirus, coronavirus, herpes simplex, parainfluenza and RSV are common causes. Symptoms tend to have a slower onset, longer duration, and less pain than strep throat. Most patients with viral pharyngitis have additional symptoms such as nasal symptoms, cough, and conjunctivitis that are very uncommon in patients with strep throat. However, in some cases viral pharyngitis can mimic streptococcal pharyngitis in every aspect except the positive bacteriological findings.

Mononucleosis

Mononucleosis, caused by EBV, occurs most frequently in adolescents and young adults, hence its nickname the “kissing disease.” The onset of the sore throat is slow and it lasts 5 to 7 days with mild to moderate pain. In addition, most patients experience significant fatigue and malaise that may last for 4 to 8 weeks. Sometimes it is the primary presenting symptom. Since the incubation period is 4 to 6 weeks, few patients remember any potential exposures. Objectively, examination of the throat reveals redness usually not as severe as in strep throat. About half the patients will have purulent exudates, with some having profuse exudates that is continuous over the posterior pharynx and tonsils. Painful anterior and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy is common, with some patients having swollen, painful lymph nodes as remote from the throat as the underarms. Patients have a low-grade fever and 90% have mildly elevated AST and ALT levels. Jaundice develops in less than 5% of patients. All patients develop some degree of splenomegaly that may not be evident upon physical examination. A CBC reveals lymphocytosis with the presence of >10% atypical lymphocytes. A positive Monospot test and elevated EBV antibody levels are diagnostic for the disease. Unfortunately, neither may be positive during the first 2 weeks of the disease and may need to be repeated to confirm the diagnosis.

Herpangina/Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease

These two disorders are caused by viruses in the enterovirus group, which includes coxsackieviruses and others. Some sources actually consider them to be different manifestations along the same disease spectrum. Both diseases usually present with severe throat pain, malaise, and difficulty swallowing and symptoms last for 7 to 10 days. Herpangina has a rapid onset and occurs most frequently in children, whereas hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) has a slightly slower onset of 12 to 36 hours and occurs in patients of all ages. Objectively, both have dermatological manifestations in more than 50% of patients. In herpangina, a maculopapular, vesicular rash appears on the trunk. In HFMD, the vesicular lesions with erythematous borders typically occur on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, as well as the buttocks in some cases. In HFMD, the fever is generally low grade, where herpangina presents with temperatures of 38.4°C to 40°C. Examination of the throat reveals varying degrees of erythema with red vesicles that ulcerate and have a red border. In herpangina, lesions are limited to the posterior pharynx and tonsillar pillars, while in HFMD they occur all over the oral cavity including tongue and gingivae. Painful cervical lymphadenopathy is common in both disorders.

Pharyngitis Due to Post-Nasal Drip

Patients with both allergic rhinitis and viral URIs can have sore throats. However, they differ in several ways from other forms of pharyngitis. Rarely is sore throat the primary complaint. While the patient may awaken with the sore throat, it usually goes away after several hours. In contrast, with most other causes of pharyngitis the pain is constant throughout the day and night. Also, the sore throat when due to post nasal drip lasts only as long as the rhinitis does. Objectively, examination of the throat reveals drainage or discharge, often in two tracks, on the posterior pharynx. When present, this drainage is often of similar consistency and appearance as the nasal discharge. There may be some mild inflammation on the soft palate or posterior pharynx.

Loss of Voice/Hoarseness

Loss of voice or hoarseness at times accompanies sore throat or it can occur by itself. The most common cause of hoarseness is acute laryngitis. Respiratory viruses such as rhinovirus, adenovirus, and coronavirus are the most frequent cause. Allergies and voice strain due to overuse are other common causes. Smokers as well as patients with GERD may also experience the symptom. Onset of the hoarseness is slow and is accompanied by other symptoms of the causative disorder. Symptoms lasting longer than 2 weeks, especially in smokers, should be referred to an ENT specialist to look for more serious causes such as laryngeal carcinoma.

Croup, also known as viral laryngotracheobronchitis, is a disease of infants and young children in which the structures implicated in the name of the disorder become inflamed due to common respiratory viruses. Occurring mostly in the winter months, the hallmark signs are abrupt onset of a nocturnal cough that sounds like a seal barking along with inspiratory stridor and trouble breathing. Most cases are mild and require no treatment other than providing humidified air for the child to breath during attacks. This can be accomplished by taking the child into the bathroom, closing the door, and turning on the hot water in the shower to fill the room with steam. The warm moist air relieves the cough, stridor, and breathing difficulties. Severe difficulty breathing, continuous stridor at rest, retractions when breathing, early cyanosis, and lethargy are all signs of severe disease that may require immediate treatment and/or hospitalization. In short, if the steam does not work well, then the child needs to be taken to a facility for definitive care.

Finally, acute epiglottitis, while rare, deserves mention. The incidence has drastically decreased in countries where routine immunization of children against Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae has been implemented. These are/were the two most common causes of the disease, although many other bacterial (and even some viral and fungal) causes have been documented. However, the rate in adults has remained constant with the average occurrence at age 45 with a gender ratio of 3:1 for males to females. It is a life-threatening infectious disease, with a 7% mortality rate in adults. It typically presents with an acute onset of sore throat, and difficult or painful swallowing. The classic sign is the sudden loss of voice as opposed to the slow onset of hoarseness and laryngitis seen in viral conditions. Patients generally present with a high fever and in later stages may experience difficulty breathing and stridor. This is a medical emergency and may require tracheostomy to prevent asphyxia and death. Therefore, patients (especially older males) presenting with a severe sore throat and sudden loss of voice must be immediately referred.

• KEY REFERENCES

1. Slavin RG, Spector SL, Bernstein IL, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of sinusitis: a practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(6 suppl):S13-S47.

2. Anon JB. Upper respiratory infections. Am J Med. 2010;123(4 suppl):S16-S25.

3. Dykewicz MS, Hamilos DL. Rhinitis and sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 suppl):S103-115.

4. Neilan RE, Rolan PS. Otalgia. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94(5):961-971.

5. Ely JW, Hanson MR, Clark EC. Diagnosis of ear pain. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(5):621-628.

6. Coker TR, Chan LS, Newberry SJ, et al. Diagnosis, microbial epidemiology and antibiotic treatment of otitis media in children: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010;304(19):2161-2169.

7. Schafer P, Baugh RF. Acute otitis externa: an update. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:1055-61.

8. Wessels MR. Streptococcal pharyngitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(7):648-655.

9. Chan TV. The patient with sore throat. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94(5):923-943.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree