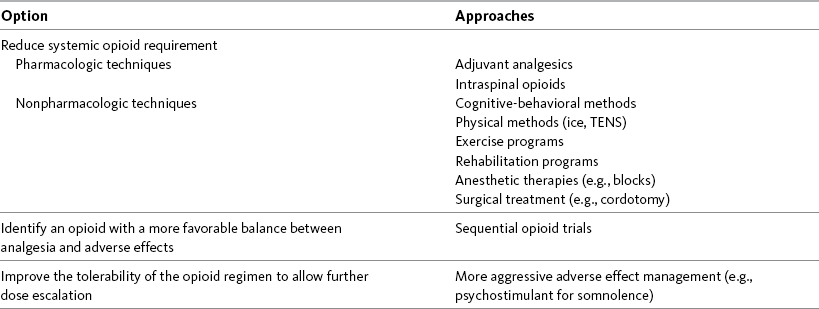

Chapter 18 WITH few exceptions, analgesia is dose-related rather than opioid-related. Thus unrelieved pain per se is not a sound reason for switching to another opioid. Other options for improving analgesia should be tried, such as increasing the opioid dose, providing a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) around the clock (ATC), or adding local anesthetic to epidural opioids. Adverse effects that are intolerable and unmanageable are more likely to be an appropriate reason to switch to another opioid (Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, 2009). Because of great interindividual variability, even opioids that bind to the same receptor site can produce adverse effects of different intensities in patients. The development of toxic effects from metabolite accumulation is a common reason for opioid rotation during long-term opioid therapy, and some recommend multiple switches if the first change in drug does not relieve symptoms (Hanks, Cherny, Fallon, 2004; Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, 2009) (see Table 18-1 for options when analgesia from opioids is limited by adverse effects). Although switching to another opioid is common and recommended under these circumstances, a Cochrane Collaboration Review concluded that randomized controlled research is lacking and the practice is based largely on anecdotal or observational and uncontrolled studies (Quigley, 2004). Table 18-1 Options When Analgesia from Opioids Is Limited by Adverse Effects TENS, Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 474, St. Louis, Mosby. Modified from Portenoy, R. K. (1998). Adjuvant analgesics in pain management. In D. Doyle, G. Hanks, & N. MacDonald (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative medicine, ed 2, New York, Oxford University Press. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. When switching an opioid-tolerant patient to an alternative opioid drug, it is wise to assume that cross-tolerance will be incomplete (Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, 2009). This means that a patient who has developed tolerance to one opioid analgesic may not be equally tolerant to another. In such cases, the starting dose of the new opioid must be reduced by at least 25% to 50% of the calculated equianalgesic dose to prevent overdosing (see Chapter 13, pp. 339-350, for the recommended approach when converting to methadone); otherwise, the full calculated equianalgesic dose of the new opioid could lead to effects such as sedation that would be greater than expected (Fine, Portenoy, the Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation, 2009; Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, 2009; Indelicato, Portenoy, 2002; Vadalouca, Moka, Argyra, et al., 2008). Even with this approach, some patients will experience underdosing and some will experience overdosing because of individual sensitivities. It is also best not to abruptly discontinue the present opioid and convert to the new opioid in one step. This could cause a significant overdose that precipitates undesirable adverse effects or an underdose that precipitates severe pain. Instead, it is best to make the transition with 50% of the current opioid dose combined with 50% of the projected dose for the new opioid for several days. From this starting point, gradual increases in the new opioid drug and decreases in the old drug can be made until the switch is complete. The higher the dose of the current opioid, the more important it is to make the transition using 50/50 dosing (see Box 18-1 for guidelines when switching from one opioid to another). The principles described above underscore the importance of careful dose selection and monitoring during opioid rotation (see Chapter 11 for more on cross-tolerance and the use of conversion charts, Box 14-6 on p. 393 for guidelines on switching from oral morphine to transdermal fentanyl, and Box 13-3 on p. 345 for guidelines on switching to methadone). It requires the clinician to have an understanding of opioid pharmacology and a commitment to tailoring the choice of opioid and dose to the patient’s individual characteristics and response (Shaheen, Walsh, Lahsheen, et al., 2009). An expert panel was convened for the purpose of establishing a new guideline for opioid rotation and recently proposed a two-step approach (Fine, Portenoy, the Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation, 2009). The approach presented in this chapter for calculating the dose of a new opioid can be conceptualized as the panel’s Step One, which directs the clinician to calculate the equianalgesic dose of the new opioid based on the equianalgesic table. Step Two suggests that the clinician perform a second assessment of the patient to evaluate the current pain severity (perhaps suggesting that the calculated dose be increased or decreased) and to develop a strategy for assessing and titrating the dose as well as determining the need for a breakthrough dose and calculating that dose (see Box 16-2 on p. 449). The specific steps of patient examples given in this chapter reflect the panel’s two-step approach (see Fine, Portenoy, the Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation, 2009). Following are several patient examples of conversions from one opioid to another, one route of administration to another, and combinations of both. The equianalgesic dose chart in Table 16-1 on pp. 444-446 is used for the necessary conversion calculations.

Switching to Another Opioid or Route of Administration

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine