Surgical Treatment of Crohn’s Disease

Fabrizio Michelassi

Govind Nandakumar

Mukta V. Katdare

Alessandro Fichera

Roger D. Hurst

Introduction

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract that can result in strictures, inflammatory masses, fistulas, abscesses, hemorrhage, and cancer. It may affect any region of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus, and often involves multiple areas simultaneously. Crohn, Ginsberg, and Oppenheimer first identified the disorder as a unique clinical entity in 1932. Although the cause of Crohn’s disease remains unknown, the prevailing theory is that, in patients with a genetic predisposition, exposure to particular environmental stimuli triggers an altered immune response, resulting in inflammation and ulceration of intestinal tissues.

The histopathology of Crohn’s disease is characterized by transmural inflammation with multiple lymphoid aggregates in a thickened submucosa. The earliest gross manifestation of Crohn’s disease is the development of small mucosal ulcerations, called aphthous ulcers, that eventually progress to larger ulcerations. These mucosal ulcerations can penetrate through the submucosa to form intramural channels that have the potential to bore deeply into the bowel wall and create sinuses, abscesses, or fistulas.

It is estimated that the incidence of Crohn’s disease in the United States is <4 new cases per year for every 100,000 persons, and the prevalence is between 80 and 150 cases per 100,000 persons. Crohn’s disease can affect patients of all ages, but the peak incidence occurs between the second and the third decades. In the United States, the incidence of Crohn’s disease is highest among whites, low among African Americans, and lowest among Hispanics and Asians. Crohn’s disease is three to four times more common in the ethnic Jewish population, and it appears slightly more predominant in women than in men.

Curative treatment for Crohn’s disease does not exist. Current medical therapy is often effective abating the progression of the disease, but even with the newer medical treatment, complications often occur that require surgical intervention. Modern principles of surgical management dictate that intestinal resections be limited, without wide margins of normal tissue. This is supported by the evidence that recurrence of Crohn’s disease is unaffected by the presence of macroscopically involved bowel at the anastomotic line, as demonstrated by the long-term results obtained with stricturoplasty or when microscopic involvement is present at the resection margin. Greater understanding of the clinical course of Crohn’s disease has led to a more conservative strategy, with surgery reserved for the treatment of complications of the disease, and bowel-sparing approaches advocated.

General Clinical Aspects

Crohn’s disease is commonly categorized according to the affected intestinal site. Approximately 40% of patients have distal ileal disease with or without involvement of the right colon. Proximal small-bowel disease without colonic involvement is observed in 30% of patients, whereas isolated colonic involvement without small-bowel disease occurs in <25% of patients. Involvement of the anorectal region, the perianal region, or both, without proximal small or large bowel is found in only 5% of patients.

Crohn’s disease may also be categorized by its clinical manifestations and grouped into one of three general entities: stricturing, perforating, or inflammatory disease. These are not truly distinct forms of the disease, but rather are terms that are used to describe the predominant gross pathologic manifestation. Stricturing Crohn’s disease results in the development of fibrotic scar tissue that constricts the intestinal lumen and may result in a partial or complete obstruction. These fibrostenotic scars are not reversible with medical therapy; therefore, once they become symptomatic, surgical intervention is required. Perforating Crohn’s disease is caused by deep mucosal ulcerations that can develop into sinus tracts, fistulas, and abscesses. The inflammatory pattern of Crohn’s disease is characterized by mucosal ulceration and bowel-wall thickening that may lead to an adynamic segment of intestine and luminal narrowing, causing obstructive symptoms in the small intestine and diarrhea in the colon.

The onset of symptoms is often insidious, with most patients presenting with complaints of intermittent abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and fever. Patients may also experience symptoms related to complications of the disease, including abdominal masses, pneumaturia, or perianal pain and swelling. The particular signs, symptoms, and complications of Crohn’s disease exhibited by a patient depend greatly on the affected sites. There is no specific laboratory test that is diagnostic for Crohn’s disease and the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease still relies heavily on the history and physical examination and it is confirmed by appropriate imaging and histopathologic examination.

Imaging

Small-Bowel Radiography

Upper intestinal contrast studies, either small-bowel follow-through or enteroclysis, are the best means for assessing the small bowel for Crohn’s disease. The radiographic abnormalities of small-bowel Crohn’s disease are often distinctive. With early Crohn’s disease, mucosal granulations with ulceration and nodularity can be identified. Thickening of the mucosal folds and edema of the bowel wall itself can be demonstrated as the disease progresses. With more advanced disease, cobblestoning becomes radiographically apparent. Small-bowel contrast studies can also provide information regarding enlargement of the mesentery, as well as formation of an inflammatory mass or abscess. Such findings are demonstrated by a general mass effect separating and displacing contrast-filled loops of small intestine. Small-bowel contrast studies can demonstrate some of the complications of Crohn’s disease, including high-grade strictures and fistulas. It is important to note, however, that small-bowel radiography may not identify all such lesions. For instance, many enteric fistulas including ileosigmoid and ileovesical fistulas are not typically demonstrated on contrast radiography. Thus, the absence of radiographic evidence for fistulization does not exclude this possibility. In addition, small-bowel studies may not demonstrate all the areas of disease with significant strictures.

While small-bowel radiographs may underestimate the extent of complicated Crohn’s disease, small-bowel studies performed by an experienced gastrointestinal radiologist are very effective as a diagnostic

tool for the disease. Besides their diagnostic utility, small-bowel radiographs can also help in assessing the extent of the disease by identifying the location and length of involved and uninvolved intestine, and by recognizing whether the disease is continuous or discontinuous with skip lesions separated by areas of normal intestine. Experienced radiologists can also assess areas of luminal narrowing and determine if they are the result of acute inflammatory swelling or are the result of fibrostenotic scar tissue. Such a distinction provides valuable information regarding the value of medical therapy versus early surgical intervention, as inflammatory stenoses are likely to respond to medical therapy while fibrotic strictures are best treated with surgery.

tool for the disease. Besides their diagnostic utility, small-bowel radiographs can also help in assessing the extent of the disease by identifying the location and length of involved and uninvolved intestine, and by recognizing whether the disease is continuous or discontinuous with skip lesions separated by areas of normal intestine. Experienced radiologists can also assess areas of luminal narrowing and determine if they are the result of acute inflammatory swelling or are the result of fibrostenotic scar tissue. Such a distinction provides valuable information regarding the value of medical therapy versus early surgical intervention, as inflammatory stenoses are likely to respond to medical therapy while fibrotic strictures are best treated with surgery.

Endoscopy

Upper and lower endoscopy allows for inspection of mucosal disease and provides an opportunity for a biopsy for histologic evaluation. Upper endoscopy is useful in the diagnosis of mucosal lesions of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum; it also easily identifies strictures and grades their severity. Characteristic colonoscopic features of Crohn’s disease include aphthous ulcers, longitudinal ulcerations, skip lesions often with rectal sparing, pseudopolyps, and strictures. Diagnosis of terminal ileal Crohn’s disease can be usually made at ileocolonoscopy, which should be performed before a capsule endoscopy is contemplated. If the ileocecal valve proves impossible to intubate, a capsule endoscopy may be considered after strictures are ruled out by a small-bowel follow-through.

Capsule Endoscopy

Capsule endoscopy is a new tool in the diagnosis and evaluation of Crohn’s disease. With this study, a small camera incorporated within a capsule size casing is swallowed and images from the camera are transmitted to a small electronic receiver worn by the patient. The image from the capsule endoscopy can detect subtle mucosal lesions that may not be apparent on small-bowel x-rays. All patients with suspected Crohn’s disease should undergo a small-bowel contrast study to exclude stricture formation prior to the capsule endoscopy, as the capsule may fail to pass through areas of narrowing and result in intestinal obstruction.

The value of capsule endoscopy in the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease has been recently evaluated in a prospective study from the Mayo clinic. In this study, the first to compare capsule endoscopy, computed tomography enterography (CTE), ileocolonoscopy, and small-bowel follow-through in the diagnosis of small-bowel Crohn’s disease in a prospective blinded trial, the sensitivity of capsule endoscopy was not significantly different from that of the other tests. A lower specificity (53%) and the need for radiography to detect asymptomatic partial small-bowel obstruction before the capsule study can be safely performed may limit the utility of capsule endoscopy as a first-line test in Crohn’s disease. Furthermore, when examining the sensitivity and specificity of different combinations of ileocolonoscopy, CTE, capsule endoscopy, and small-bowel follow-through, the authors found that ileocolonoscopy with either CTE or small-bowel follow-through was more accurate than capsule endoscopy with CTE, small-bowel follow-through, or ileocolonoscopy, because of the lower specificity of capsule endoscopy. These findings suggest that capsule endoscopy should be reserved for cases in which ileocolonoscopy plus small-bowel radiography is not diagnostic, but the suspicion of Crohn’s disease remains high.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) findings of uncomplicated Crohn’s disease are nonspecific and routine CT is not necessary for the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. CT, however, is very useful in identifying the complications associated with Crohn’s disease. Specifically, CT can readily identify thickened and dilated intestinal loops, inflammatory masses, or abscesses. CT scan can also demonstrate hydronephrosis resulting from retroperitoneal fibrosis and ureteral narrowing. CT scans are often the most sensitive indicator for the presence of an enterovesical fistula as identified by the presence of air within the urinary bladder.

More recently cross-sectional imaging techniques are playing an increasing role in the imaging of patients with Crohn’s disease. In recent studies, evaluating the performance characteristics of cross-sectional enterography, CTE has been shown to have a higher sensitivity than barium small-bowel follow-through. At some institutions, CTE combined with ileocolonoscopy has become a first-line test for the diagnosis and staging of Crohn’s disease. CTE exploits the high spatial resolution and speed of modern CT, using large volumes of neutral oral contrast agents to generate detailed images of the small-bowel wall, lumen, and mesentery. In addition, CTE has several potential advantages over barium studies in the identification of fistulizing disease. Unlike traditional fistulography, CTE does not suffer from superimposition of bowel loops, and CTE displays the perienteric mesentery and retroperitoneal and abdominal wall musculature, typically involved by fistulas. Sinus tracts and abscesses can also be readily characterized by CTE.

However, given the recent concerns about radiation-induced cancer arising from medically related CT, particularly in the setting of Crohn’s disease, which can lead to multiple exposures to radiation in young patients, the role of CTE in assessing younger patients is being increasingly questioned. MR enterography (MRE) has been shown in a recent study to have similar sensitivities for detecting active small-bowel inflammation than CTE without requiring ionizing radiation. Therefore, MRE should be considered an alternative to CTE, when radiation exposure is a concern to provide complementary information to ileocolonoscopy in the diagnosis Crohn’s disease.

Although medical therapy can only palliate the symptoms of Crohn’s disease, it may afford long periods of remission and delay surgical treatment. However, <80% of patients will still require surgical intervention during their lifetime. The main goal of surgery is to treat complications and to palliate symptoms, while minimizing complications and side effects.

Fistulas

Although one-third of patients with Crohn’s disease will develop an intestinal fistula, these are rarely the primary indication for surgery. Surgical treatment is generally reserved for intestinal fistulas that connect with the genitourinary tract and result in repeated urinary tract infections or renal impairment; for enterocutaneous and enterovaginal fistulas that cause the patient personal embarrassment or discomfort; and for fistulas that result in the functional bypass of a major intestinal segment, causing malabsorption and diarrhea.

Inflammatory Masses and Abscesses

Abscesses that occur in the setting of Crohn’s disease are often the result of sealed perforations of the bowel. They are most frequently located in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen or along the descending colon. Most abscesses can be treated initially with percutaneous CT-guided drainage and antibiotics. However, an abscess usually originates from a severely diseased segment

of bowel and thus, without a resection of the involved segment, is likely to recur or result in an enterocutaneous fistula. Therefore, after successful interventional drainage, elective surgical resection is recommended. The presence of abscesses not amenable to percutaneous drainage, such as multilocular abscesses, multiple interloop abscesses, or inflammatory masses that are refractory to antibiotic therapy, is an indication for surgical intervention.

of bowel and thus, without a resection of the involved segment, is likely to recur or result in an enterocutaneous fistula. Therefore, after successful interventional drainage, elective surgical resection is recommended. The presence of abscesses not amenable to percutaneous drainage, such as multilocular abscesses, multiple interloop abscesses, or inflammatory masses that are refractory to antibiotic therapy, is an indication for surgical intervention.

Perforation

Free perforation of the small or large bowel only occurs in <1% of patients with Crohn’s disease. The clinical signs of peritonitis or the identification of free intraperitoneal air on a plain radiograph or CT scan are diagnostic of free perforation. Once diagnosed, urgent surgery is required, with resection of the perforated bowel and any associated involved segments. A stoma may be necessary in the presence of significant intra-abdominal contamination.

Obstruction

A partial or complete intestinal obstruction may require surgical intervention. A partial intestinal obstruction that is caused by acute inflammation and bowel-wall thickening can often be treated with medical therapy. However, obstructions that are caused by high-grade fibrostenotic lesions will not respond to medical management and are an indication for surgery. In an effort to limit the length of bowel to be resected, attempts initially should be made to treat partial or complete intestinal obstructions conservatively with nasogastric decompression, intravenous hydration, and intravenous steroids, allowing for a definitive procedure to be conducted electively when decompression is achieved.

Carcinoma

Crohn’s disease is a risk factor for adenocarcinoma of the small bowel and the colon. The incidence of cancer occurrence correlates with the duration and extension of disease. The risk of malignancy also increases in defunctionalized segments of bowel. Therefore, bypass surgery of the small intestine should be avoided, and defunctionalized rectal stumps should either be restored to their function or excised.

Hemorrhage

Severe hemorrhage in the setting of Crohn’s disease is extremely rare and often requires definitive surgical treatment. Massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage occurs most frequently from Crohn’s colitis. Hemorrhage from Crohn’s disease of the small bowel tends to be indolent with episodic or chronic bleeding that may require intermittent blood transfusions but rarely requires emergent surgical intervention. However, the risk of a recurrence is high with spontaneous cessation of a small-bowel hemorrhage; therefore, elective surgery of the actively diseased segment should be considered after the first episode of hemorrhage.

Toxic Megacolon

Toxic megacolon is a rare but potentially fatal complication of Crohn’s disease. Unstable patients or patients who do not readily respond to supportive measures, including adequate fluid resuscitation, antibiotics, and medical therapy, require surgery. A subtotal colectomy with creation of an ileostomy is the preferred surgical option. The decision between creating a mucous fistula and closing the distal rectosigmoid stump is based on the degree of inflammation and disease of the distal bowel.

Growth Retardation

Twenty-six percent of children with Crohn’s disease experience growth retardation as a result of either steroid treatment or the malnutrition associated with active intestinal disease. Persistent growth retardation in the face of adequate medical and nutritional therapy is an indication for surgical intervention.

Failure of Medical Treatment

Failure of medical treatment, the most common indication for surgery, occurs when (a) maximal medical treatment proves inadequate; (b) patients who are asymptomatic on maximal induction medical therapy develop recurrence of symptoms with tapering of these medications that do not have an acceptable safety profile for use as maintenance therapy; (c) the disease progresses with worsening symptoms or a complication arises despite maximal medical treatment; or (d) the patient experiences significant treatment-related complications.

A complete assessment of the gastrointestinal tract is required prior to surgery to evaluate the full extent of disease and any associated complications that may require management before surgical intervention. Small-bowel follow-through or enteroclysis adequately assesses the entire small intestine. Crohn’s disease is a relative contraindication for capsule endoscopy because of the high incidence of strictures. However, if a contrast study has ruled out lesions that could prevent capsule passage and clinical questions are still unanswered, capsule endoscopy can be safely and effectively used. A colonoscopy provides the best evaluation of the colon and rectum and, with the intubation of the terminal ileum, biopsies can be obtained to confirm the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. If colonic strictures prevent the passage of a colonoscope, a barium enema may be helpful. If the patient presents with a fever or an abdominal mass, a CT scan should be obtained to assess for the presence of an intra-abdominal abscess and enable percutaneous drainage.

The use of mechanical bowel preparation is controversial in patients with Crohn’s disease during an acute attack and in the presence of severe diarrhea, and is clearly contraindicated when a perforation or a complete obstruction is present. All patients should be administered prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics and patients on long-term steroid therapy should receive stress-dose steroids. In the event that the patient cannot undergo primary restoration of the gastrointestinal continuity, a potential stoma site should be marked preoperatively.

To avoid clinical deterioration prior to elective surgery, we instruct our patients to continue to take 5-ASA and steroid therapy as previously prescribed until the day before surgery. Because anti-TNF agents have been associated in some reports with an increased risk for perioperative infections and anastomotic leaks, we will typically hold the last dose of infliximab or adalimumab prior to surgery. In addition, for patients who happen to be on methotrexate, this medication will be discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to surgery.

Site-Specific Planning

Esophagus, Stomach, and Duodenum

Gastroduodenal involvement in Crohn’s disease is reported in only 2% to 4% of cases and is rarely confined to only the gastroduodenal segment. In a study conducted by Yamamoto et al., 96% of patients with gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease had disease elsewhere. In general, >50% of patients have known distal involvement before the diagnosis of gastroduodenal disease, and <30% of patients present with duodenal and

distal Crohn’s disease simultaneously. The most common distribution of gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease is contiguous involvement of the gastric antrum, pylorus, and the duodenal bulb. However, in a series of 89 patients from the Lahey clinic, isolated duodenal disease with gastric sparing was reported in 40% of patients.

distal Crohn’s disease simultaneously. The most common distribution of gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease is contiguous involvement of the gastric antrum, pylorus, and the duodenal bulb. However, in a series of 89 patients from the Lahey clinic, isolated duodenal disease with gastric sparing was reported in 40% of patients.

Crohn’s disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract may produce symptoms of nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, or odynophagia, and is often misdiagnosed as peptic ulcer disease. The failure of antiulcer medications to resolve symptoms often leads to further investigation, including endoscopy and upper gastrointestinal imaging. Based on radiologic, endoscopic, and pathologic studies, the earliest findings in gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease are edema, aphthous ulceration, nodularity, cobblestoning, and irregular mucosal thickening, which often progresses to stricture formation and stenosis.

The use of medications to suppress gastric acid secretion and corticosteroid therapy is effective for patients with mild or moderate gastrointestinal Crohn’s disease. However, approximately one-third of patients affected by gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease will require surgical intervention in their lifetime, most commonly for obstruction resulting from stenotic disease. Intractable pain, bleeding, and fistulas are also indications for surgical treatment. Options for surgical management of complicated gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease include bypass, stricturoplasty, and, less frequently, resection.

Traditionally, the “gold standard” for treating obstruction of the first and second portions of the duodenum has been to bypass the duodenum via a gastrojejunostomy. This procedure effectively relieves duodenal obstructive symptoms caused by Crohn’s strictures, but it carries a high risk for stomal ulcerations. Therefore, it is suggested that a vagotomy be performed along with the gastrojejunostomy. A highly selective vagotomy is preferred over a truncal vagotomy to reduce the incidence of vagotomy-related diarrhea. If the stricturing disease is limited to the third or fourth portions of the duodenum, a Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy to the proximal duodenum is preferred over a gastrojejunostomy because it eliminates the concern of developing acid-induced marginal ulceration.

Because of the frequency of morbidity and risk for recurrence with gastrojejunostomy, alternatives to bypass procedures have been sought. Ross et al. published a series of patients who had undergone bypass procedures for obstructing duodenal Crohn’s disease and reported a 70% reoperation rate for complications including marginal ulceration, recurrent obstruction, and duodenal fistula formation with a follow-up of 17 years. Given the focal nature of stricturing disease of the duodenum, stricturoplasty has become a viable option. The type of stricturoplasty depends on the location, the length, and the number of strictures present. Strictures in the first, second, and proximal third portions of the duodenum can effectively be managed with a Heineke-Mikulicz stricturoplasty. To safely accomplish a Heineke-Mikulicz stricturoplasty, the duodenum must be fully mobilized with a generous Kocher maneuver. Strictures of the first and fourth portions of the duodenum are best handled with a Jaboulay and a Finney stricturoplasty, respectively, constructed by creating an enteroenterostomy between the greater curvature of the stomach and the first portion of the duodenum, or the fourth portion of the duodenum and the first loop of the jejunum.

The safety and efficacy of stricturoplasty in the management of obstructive gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease has been studied in a number of recent series. In a retrospective study conducted by Yamamoto et al., 13 patients underwent stricturoplasty for obstructive duodenal Crohn’s disease. Eleven of 13 patients had follow-up for more than 8 years. Three of 13 patients (23.1%) required further surgery because of early postoperative complications, and 6 of 13 patients (46.2%) developed recurrent strictures at the previous stricturoplasty site. When compared with bypass surgery, the authors found that, after a median follow-up of 143 months, 9 of 13 patients (69.2%) who underwent stricturoplasty required reoperation, compared with 6 of 13 patients (46.2%) treated with bypass after a median follow-up of 192 months. Worsey et al. reported a more favorable experience with duodenal stricturoplasty when they compared this procedure with bypass surgery for the treatment of duodenal Crohn’s disease in a retrospectively study. They found that after a mean follow-up of 8 years, 1 of 21 patients (4.8%) who underwent a bypass procedure required reoperation for recurrent disease, and after a mean follow-up of 3.6 years, 1 of 13 patients (7.7%) treated by stricturoplasty required reoperation for recurrence, a difference that was not significant. They concluded that although the follow-up was shorter for stricturoplasty, it afforded the same rates of symptom relief and reoperation, but had fewer complications than traditional bypass surgery.

In recent years, stricturoplasty, which has the advantage of avoiding a blind-loop syndrome or stomal ulceration, has replaced bypass as the operation of choice for treatment of short obstructive duodenal Crohn’s disease. However, if the duodenal stricture is lengthy, multiple strictures are present, or the tissues around the stricture are too rigid or unyielding, then a stricturoplasty should not be performed, but rather an intestinal bypass procedure should be undertaken.

Ileoduodenal or coloduodenal fistulas may also complicate gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease. The fistula usually arises from a diseased ileocolic segment after a previous ileocolic resection or the transverse colon and drains into the duodenum or stomach secondarily. Most duodenoenteric fistulas are small in caliber and asymptomatic, and they are identified with preoperative small-bowel radiography or discovered at the time of surgery. Larger fistulas may present with symptoms of malabsorption and diarrhea caused by the shunting of duodenal contents into the distal small bowel. Most duodenal fistulas are located away from the juncture of the duodenal wall at the head of the pancreas and, therefore, after adequate mobilization, resection of the primary segment with primary closure of the duodenal defect is often sufficient. Larger or complex fistulas that are involved with a significant degree of inflammation need to be handled with great care at surgery to limit the size of the duodenal defect resulting from resection of the fistula. When a large duodenal defect is present, a Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy or a jejunal serosal patch may be required for adequate closure. Duodenal resections are almost never necessary from gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease and should be considered the surgical option of last resort.

Operative Technique for Stomach and Duodenum

Gastrojejunostomy

A gastrojejunostomy and vagotomy are best performed though a midline incision. The vagotomy should be performed before the bypass to avoid any potential tension on the fresh anastomosis. The gastrojejunostomy can be performed either in an antecolic or a retrocolic fashion with either a handsewn or stapled anastomosis. If the colon is not involved, most surgeons prefer a simple side-to-side retrocolic approach, in which a window is made in the avascular plane of the transverse mesocolon exposing the posterior wall of the stomach. Care is taken to identify the middle colic artery to avoid injuring it during the dissection. The most proximal loop of jejunum that lies tension-free next to the greater curvature of the stomach is selected. Two stay sutures are placed to hold the stomach and bowel

together. In a stapled anastomosis, an enterotomy and gastrotomy are then made and the linear stapler is inserted and fired. The gastrotomy and enterotomy are then closed using two layers of interrupted 3-0 sutures. With a handsewn anastomosis, a posterior layer of interrupted 3-0 silk sutures is used to approximate the stomach and the segment of jejunum. An enterotomy and a gastrotomy are made, and absorbable 3-0 sutures are used to make a continuous inner suture layer. An outer anterior layer of interrupted 3-0 silk sutures is then fashioned to complete the anastomosis and the defect in the mesocolon is closed.

together. In a stapled anastomosis, an enterotomy and gastrotomy are then made and the linear stapler is inserted and fired. The gastrotomy and enterotomy are then closed using two layers of interrupted 3-0 sutures. With a handsewn anastomosis, a posterior layer of interrupted 3-0 silk sutures is used to approximate the stomach and the segment of jejunum. An enterotomy and a gastrotomy are made, and absorbable 3-0 sutures are used to make a continuous inner suture layer. An outer anterior layer of interrupted 3-0 silk sutures is then fashioned to complete the anastomosis and the defect in the mesocolon is closed.

Small Bowel

The small bowel is the most frequently affected gastrointestinal site in Crohn’s disease. Any portion of the small bowel may be diseased, but the terminal ileum is most commonly involved. Ninety percent of patients with Crohn’s disease of the small bowel experience abdominal pain caused by obstructive or septic complications, which may be associated with fevers, anorexia, or weight loss. Unremitting obstructive symptoms or an episode of high-grade obstruction indicate a severe degree of stenosis that will likely require surgical intervention. Crohn’s disease of the small intestine can also give rise to the formation of fistulas and abscesses. Patients may develop a palpable mass, usually located in the right lower quadrant, representing an abscess, a phlegmon, or a thickened loop of bowel. The differential diagnosis for small-bowel Crohn’s disease includes irritable bowel syndrome, acute appendicitis, intestinal ischemia, radiation enteritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, and gynecologic malignancies.

Upper intestinal contrast studies, either small-bowel follow-through or enteroclysis, are the best means of assessing the small bowel for Crohn’s disease. With early Crohn’s disease, a mucosal granular appearance with ulceration and nodularity can be identified radiologically. As the disease progresses, thickening of the mucosal folds and edema of the bowel wall become evident, eventually leading to the cobblestoning that is characteristic of advanced disease. Small-bowel studies may occasionally demonstrate complications including high-grade strictures, fistulas, and abscesses, but are known to underestimate the extent of complicated Crohn’s disease. Small-bowel studies may also be used to identify the location and length of involved intestine, to recognize whether the disease is continuous or discontinuous with skip lesions, and to determine whether areas of luminal narrowing are caused by acute inflammation or fibrostenotic scar tissue.

Surgical intervention in patients with Crohn’s disease of the small bowel is limited to the treatment of acute and chronic complications that do not respond to medical management. A study conducted at the Cleveland Clinic found that with disease of 10 years’ duration, 90% of patients with ileocolitis and 70% of patients with only ileal involvement required surgery. The researchers found that the indication for surgery was intestinal obstruction in 55% of patients and intestinal fistulas or abscesses in 32% of patients. Although the surgical approach may differ based on the indication for surgery and the site of disease, adherence to the principle of bowel conservation is preferred.

Operative Technique for Small Bowel

Small-Bowel Resection

A planned small-bowel resection is preceded by the exploration of all four abdominal quadrants and of the entire small bowel for evidence of coexisting Crohn’s disease; this is mandatory, as up to 15% of patients will present with skip lesions. If areas of stenosis are suspected but not evident on serosal inspection, a Foley catheter with a balloon inflated to 2 cm and inserted through an enterotomy can be used to assess these sites. Before and after resection, the length of bowel should be measured and documented. The length of the diseased segment, the length of the resected segment, and the distance between strictures should be measured and recorded as well. The margins of macroscopic disease are then tagged with stay sutures and the diseased segment and its adjacent normal bowel are mobilized and isolated to minimize the possibility of contamination. In addition, the contents of the small bowel are milked either proximally or distally beyond the margins of the potential anastomosis. Matted loops of small bowel or omentum are often found adjacent to the diseased segment, especially if the terminal ileum is involved. Care must be taken to adequately mobilize the affected areas, and mobilization of the ascending colon may even be required. The matted loops of bowel can then be separated with a combination of blunt and sharp dissection, and the area to be resected can be inspected. The length of the resection margin has been debated, but numerous randomized trials have reported that resection need only encompass grossly apparent disease and that wider resections do not improve surgical outcome.

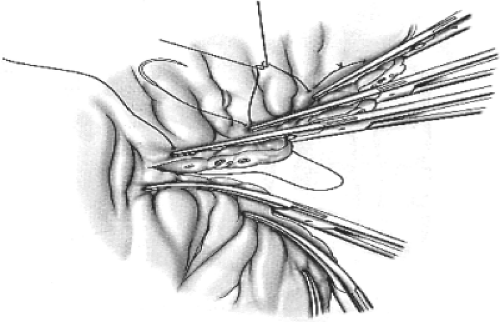

Fig. 1. Management of thickened Crohn’s mesentery. Hemostasis is obtained by placing overlapping hemostats across the bowel and then suture-ligating them. |

Division of the thickened mesentery of the involved small bowel is often the most challenging aspect of the procedure. Because the extent of mesenteric dissection does not affect long-term results, the mesentery should be divided at the most advantageous level. It may be impossible to identify and isolate individual mesenteric vessels. Therefore, overlapping hemostatic clamps are commonly applied on either side of the intended line of transection and then the mesentery is divided between the clamps, with the tissue contained within the clamps suture-ligated using 0 or 1-0 absorbable sutures. Additional hemostatic mattress sutures may be needed to control bleeding (Fig. 1). Recently, newer sealing devices that employ bipolar technology have been developed for use in open and laparoscopic surgery that allow for safe control of vessels up to 7 mm in diameter. These instruments have reduced blood loss and the length of the procedure, and have simplified intraoperative management of the often thickened and friable mesentery of patients with Crohn’s disease. In spite of the technical challenges posed by the hyperemic and thickened mesentery, the risk of

postoperative hemoperitoneum requiring surgical intervention has been reported to be <0.5%.

postoperative hemoperitoneum requiring surgical intervention has been reported to be <0.5%.

The bowel may be anastomosed in an end-to-end, end-to-side, or side-to-side fashion using a handsewn or a stapled technique. In our practice, the bowel is anastomosed in a double-layered, handsewn, either end-to-end or side-to-side fashion. Recurrent Crohn’s disease after an ileocolic resection is likely to occur at the ileocolonic anastomosis or in the preanastomotic ileum. A side-to-side anastomosis is wider than an end-to-end or end-to-side anastomosis, and thus theoretically should lead to less fecal stasis and would require a longer period of time to stricture down to a critical diameter. However, clinical data have not demonstrated a significant clinical benefit for one configuration over another.

Resection with primary anastomosis can usually be performed with a high degree of safety, and small-bowel anastomotic dehiscence rates can be kept to <1%. The decision to perform either a primary anastomosis or form a stoma depends on the overall condition of the patient and the conditions under which the procedure is performed. In the event that the procedure is emergent, the patient has suboptimal nutritional parameters, is on high-dose steroids or immunosuppressive agents, or diffuse peritonitis is present, formation of a stoma may be prudent. In these circumstances, the proximal end of the bowel may be brought out as a stoma.

When managing Crohn’s disease of the small bowel, it is important to consider the natural history of the disease. Reoperative rates have been reported to be as high as 60%, especially in patients undergoing resection of the small bowel. With each subsequent resection, the potential for intestinal insufficiency and short-gut syndrome increases. Therefore, nonresectional options such as stricturoplasty have gained popularity as an alternative to lengthy resections in the treatment of stricturing Crohn’s disease of the small intestine.

One of the earliest reports of intestinal stricturoplasty to treat ileal strictures secondary to intestinal tuberculosis was by Katariya et al. In the 1980s, Lee and Papaioannou began using this technique to treat fibrostenotic strictures in patients with Crohn’s disease. The advantage of a stricturoplasty lies in the preservation of the intestinal absorptive capacity of the normal segments of bowel located between strictures. Stricturoplasties can either be performed alone or in conjunction with a resection. However, they are best performed in the presence of either long segments of stricturing disease or multiple short strictures in which a resection would result in the loss of a lengthy segment of bowel or in patients with multiple prior resections. Stricturoplasties are also indicated when they offer a simpler alternative to resection, as is the case with short recurrent disease at a previous anastomotic site. Stricturoplasties are contraindicated in the presence of generalized intra-abdominal sepsis, acutely inflamed phlegmonous intestinal segments, fistulas, abscesses, or long, tight strictures with thick unyielding intestinal walls. Whether a stricturoplasty is performed and what technique is used depends on the number of strictures, the length of each stricture, and the distribution of strictures and intervening normal small bowel.

Heineke-Mikulicz Stricturoplasty

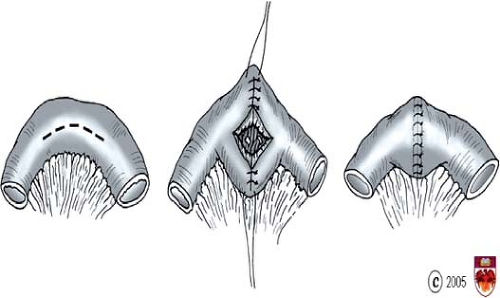

The most commonly performed stricturoplasty is the Heineke-Mikulicz stricturoplasty (Fig. 2). As with bowel resection, when a stricturoplasty is performed, the entire small bowel must first be inspected by paying careful attention to the location and length of the strictures and the length of the remaining bowel. Two stay sutures are placed along the antimesenteric border ∼1 cm proximal and distal to the stricture site. A longitudinal incision is made along the antimesenteric border of the stricture. This incision should extend for 1 to 2 cm into the normal pliable bowel on either side of the stricture. Once the enterotomy is made, the area of the stricture should be closely examined. A biopsy with frozen section should be obtained if there is any concern that the stricture may harbor a malignancy. The lumen of the bowel should also be inspected for other areas of stricturing disease. If needed, a Foley catheter can be introduced through the enterotomy, as previously described. Hemostasis should be obtained with precise application of electrocautery. The longitudinal enterotomy is then closed in a transverse fashion with either a single or double suture layer. The Heineke-Mikulicz stricturoplasty is appropriate for strictures 2 to 3 cm in length.

Finney Stricturoplasty

The Finney stricturoplasty is appropriate for strictures up to 15 cm in length. A stay suture is placed on the midportion of the strictured site. The strictured segment is then folded onto itself into a U shape (Fig. 3). A row of seromuscular sutures is placed between the two arms of the U, and a longitudinal U-shaped enterotomy is then made, paralleling the row of sutures. The mucosal surface is examined, and biopsies with frozen section are taken if there are concerns of a malignancy. Full-thickness sutures are then placed in a continuous single layer beginning at the posterior wall of the apex of the stricturoplasty and continued down to approximate the proximal and distal ends of the enterotomy. This full-thickness suture line is continued anteriorly to close the stricturoplasty. A row of seromuscular Lembert sutures is then placed anteriorly. One drawback of this procedure is that a very long Finney stricturoplasty may result in a functional bypass with a large lateral diverticulum, which can be at risk for bacterial overgrowth.

Side-To-Side Isoperastaltic Stricturoplasty (Michelassi Stricturoplasty)

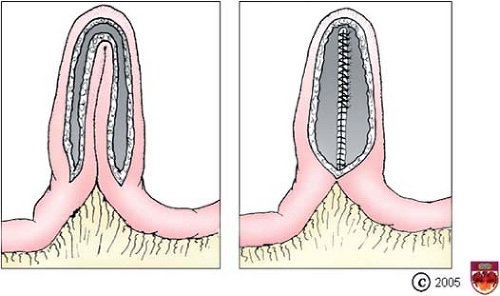

In some cases, multiple stricturoplasties may be required to avoid a long resection. In general, repeated Heineke-Mikulicz or Finney stricturoplasties should be separated from each other by at least 5 cm to avoid forming a bulky segment of intestine and placing tension on each suture line. Patients with multiple strictures that are grouped close together and a long segment of stricturing disease (>20 cm in length) are best managed with an isoperistaltic side-to-side stricturoplasty. With this technique, the mesentery of the strictured segment is first divided at its midpoint and the diseased loop of small bowel is severed between atraumatic intestinal clamps. The proximal and distal ends of bowel are then placed in an isoperistaltic side-to-side fashion. Stenotic regions of one loop are placed adjacent to dilated areas of the other loop. Division of some of the mesenteric vascular arcades may facilitate the positioning of the two limbs over each other. A layer of interrupted seromuscular Cushing stitches using nonabsorbable 3-0 suture is used to approximate the two loops of bowel. Longitudinal enterotomies are then performed on both loops (Fig. 4), with the intestinal ends tapered to avoid blind stumps. After obtaining adequate hemostasis with suture ligation or electrocautery, an internal row of full-thickness 3-0 absorbable sutures is placed anteriorly as a running Connell stitch and reinforced with an outer layer of interrupted seromuscular Cushing stitches using nonabsorbable 3-0 suture.

Unlike resection with primary anastomosis in which the tissue is removed to grossly normal margins and sutures are placed in healthy bowel, stricturoplasty is fashioned in affected bowel and suture lines are placed within scarred and diseased tissue, raising concerns of rapid recurrence and perioperative complications. However, a number of studies have reported that stricturoplasties result in prompt resolution of symptoms and weight gain without a significant increase in dehiscence, abscesses, or enteric fistulas when compared with traditional intestinal resections. In addition, disappearance or attenuation of disease that existed at the stenotic site has been observed. Long-term results from our own series demonstrate an overall complication rate of 12%, with a dehiscence rate of 1.7%, and a 2- and 5-year recurrence rate of 15% and 22%, respectively. This recurrence rate is similar to the one reported in a large series published by Ozuner and Fazio with a 5-year incidence of reoperations, with recurrence of 28%. Tichansky conducted a meta-analysis of 15 studies addressing stricturoplasties performed for small-bowel Crohn’s disease with a follow-up of >2 years in most studies. They reported an overall postoperative complication rate of 13% (66 of 506 patients), and a 25.5% recurrence rate requiring 132 surgical procedures. Interestingly, the majority of recurrences occurred at sites distant from the stricturoplasty sites; the rate of recurrence at the stricturoplasty sites was only 8.5%.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree