Abdominal trauma can be associated with injuries to any abdominal organ. Major sources of hemorrhage include solid organs (e.g., liver, spleen, kidneys) and major vessels in the retroperitoneum (e.g., aorta, inferior vena cava [IVC], renal vessels) or mesentery. Peritonitis may result from bile leak or from any injury to a hollow viscus (e.g., bowel, biliary tree, pancreas).

Liver injuries may occur following either blunt (e.g., motor vehicle crash, fall) or penetrating (e.g., gunshot or stab wound) trauma to the abdomen.

The liver is one of the most commonly injured organs following blunt trauma. Impact to the lower right chest or the abdomen puts the patient at risk of liver injury. Any high-energy mechanism should raise concern of intraabdominal injury.

The liver, due to its large surface area, is frequently injured in penetrating abdominal or lower thoracic trauma. The path of gunshot wounds to the torso cannot be determined based on physical examination alone.

Table 1: Grading of Liver Injuries

Grade

Injury Description

I

Hematoma

Subcapsular, <10% surface area

Laceration

<1 cm parenchymal depth

II

Hematoma

Subcapsular, 10%-50% surface area; intraparenchymal, <10 cm diameter

Laceration

1-3 cm parenchymal depth, <10 cm length

III

Hematoma

Subcapsular, >50% surface area or expanding; intraparenchymal, >10 cm diameter or expanding, or ruptured

Laceration

>3 cm parenchymal depth

IV

Laceration

Parenchymal disruption involving 25%-75% of hepatic lobe or 1-3 Couinaud’s segments in a single lobe

V

Laceration

Parenchymal disruption involving >75% of hepatic lobe or >3 Couinaud’s segments in a single lobe

Vascular

Juxtahepatic venous injuries

VI

Vascular

Hepatic avulsion

Advance one grade for multiple injuries up to grade III.

From Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Jurkovich GJ, et al. Organ injury scaling: spleen and liver (1994 Revision). J Trauma. 1995;38:323-324.

Abdominal pain or tenderness on examination raise concern for abdominal injury; however, patients may have severe liver injuries in the absence of pain or tenderness. Vital signs are a critical component of the assessment of trauma patients, as the decision to proceed with surgical (versus nonoperative) management is primarily based on physiologic condition of the patient. The vast majority of liver injuries are managed nonoperatively.

Ultrasound—in particular, the focused abdominal sonographic examination for trauma (FAST)—is increasingly used as an initial triage tool in trauma patients. Following blunt trauma, the finding of free fluid in the abdomen in the presence of shock is an indication to proceed to exploratory laparotomy (LAP) without delay. The finding of hemoperitoneum on FAST exam in the absence of hemodynamic instability is not an indication for LAP; injuries to abdominal wall, omentum, or liver often stop bleeding spontaneously and do not require any interventions.

The FAST exam is less useful in penetrating trauma victims. Those with gunshot wounds should undergo immediate LAP. Those with stab wounds should undergo LAP if they exhibit shock, evisceration, or peritonitis. Otherwise, they should be admitted for serial clinical assessments to detect ongoing hemorrhage or hollow viscus injury.

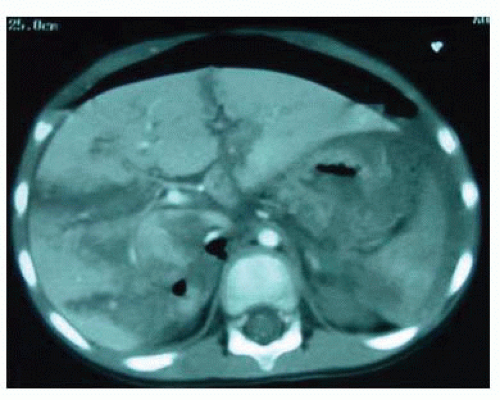

Most liver injuries due to blunt trauma are diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) (FIG 1). CT is indicated in any patient with major abdominal blunt trauma mechanism, abdominal pain or tenderness, hemoperitoneum on FAST exam in a stable patient, pelvic fractures, or the inability to clinically assess the abdominal exam and the potential

for abdominal trauma (e.g., a patient with severe traumatic brain injury following motor vehicle crash). Specific to liver laceration, the identification of intravenous contrast extravasation warrants treatment rather than observation.

Arteriography with embolization can be selectively employed as a primary treatment or as an adjunct to surgical management of liver lacerations with arterial hemorrhage. This may be employed more frequently in centers with hybrid operating room (OR)/interventional radiology (IR) suites.

Cholangiography is sometimes useful to determine whether there is biliary injury and ongoing bile leak. This is generally performed later in the postinjury course. The presence of a biliary injury and bile leak generally calls for intervention either surgical or endoscopic.

Magnetic resonance imaging has little role in the management of liver trauma.

Severe abdominal pain or tenderness, peritonitis, evisceration, or shock with a presumed abdominal injury warrant LAP.

Following stab wounds, the presence of shock, evisceration, or peritonitis is a clear indication for LAP. Gunshot wound to the abdomen, given its high association with significant injury, is an indication for LAP regardless of the initial physical findings.

Prior to taking the patient to the OR, the surgeon should communicate with the OR team regarding the suspected diagnoses and planned interventions, anticipated blood loss and transfusion requirements, positioning and incisions, extent of skin preparation, the need for imaging, and any special equipment needs.

The patient should be positioned supine. There is no advantage to tucking the arms. In the setting of trauma, it is best to leave both arms out to allow the anesthesiologist’s access for venous and arterial catheterization and sampling.

Exploratory LAP for trauma should be performed through a generous midline abdominal incision. Although it may not initially extend from the xiphoid to pubis, as is classically suggested, once a major liver injury is identified, extension up to the xiphoid process is recommended to afford optimal exposure. Some elective liver surgery is performed through right or bilateral subcostal incisions, with or without cephalad extension in the midline. This may be chosen if the operation is performed later in the patient’s clinical course for complications of liver injury, typically bile leak. However, this may limit access to the lower abdomen in the event there are multiple injuries. If a midline incision has been made, the surgeon should not hesitate to extend the incision to the right if necessary. Adequate exposure is critical to repairing major hepatic injuries.

The initial objective of trauma LAP is to determine if there is exsanguinating hemorrhage and from where it emanates. Blood must be evacuated and the source identified. Primary culprits are solid organs, retroperitoneal vessels, and mesentery. The surgeon should be able to rapidly assess the liver for major lacerations, by inspecting it and palpating its surface.

The first step in hepatic hemorrhage control is manual compression (FIG 2). This should be able to control the vast majority of liver bleeding. The importance of simultaneous aggressive resuscitation cannot be overemphasized. Restoration of blood volume and maintenance of tissue perfusion, correction of coagulopathy, and active warming of the patient are critical to avoid the “bloody vicious cycle” that can lead to early mortality.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree