Daniel P. Alford, MD, MPH, FACP, FASAM

84

PERIOPERATIVE CARE OF THE ALCOHOL-DEPENDENT PATIENT

The prevalence of alcohol use disorders is as high as 40% in emergency room and various surgical inpatient settings and up to 50% in patients with trauma. The incidence of symptomatic alcohol withdrawal is two to five times higher in hospitalized trauma and surgical patients. Chronic alcohol use can increase the risk of postoperative complications through immune suppression, reduced cardiac function, and dysregulated homeostasis including alterations in platelet production, aggregation, and changes in fibrinogen levels.

Preoperative Evaluation

The preoperative evaluation should assess for the risk of acute alcohol withdrawal and the presence of diseases associated with chronic alcohol use, including screening using validated questionnaires such as the CAGE, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption, or a single-item screening question. Screening for risk of withdrawal should include one or more of the following questions:

- Have you ever gone through alcohol withdrawal, such as having the shakes?

- Have you ever had problems or gotten sick when you stopped drinking?

- Have you ever had a seizure or delirium tremens, been confused, after cutting down or stopping drinking?

Risk factors associated with severe and prolonged alcohol withdrawal include amount and duration of alcohol use, prior withdrawal episodes, recurrent detoxifications, older age, and comorbid diseases. It is also important to note that sedatives and analgesics given during surgery and the postoperative period may delay, partially treat, or obscure some symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Physical examination should evaluate for evidence of liver, pancreatic, nervous system, and cardiac disease. The spectrum of alcoholic liver disease ranges from fatty liver with normal or mild elevations in liver function tests to acute hepatitis and cirrhosis. Pancreatitis can present as acute and chronic abdominal pain as well as exocrine and endocrine dysfunction. Alcohol-associated dementia occurs in approximately 9% of alcoholics. Korsakoff syndrome, hepatic and Wernicke encephalopathy, myelopathies, and polyneuropathies are other nervous system disorders associated with long-term regular heavy alcohol use. These neurologic conditions can worsen during the perioperative period and may be confused with other postoperative neurologic complications. Preoperative evaluation for congestive heart failure should be considered because up to one third of patients with long-standing heavy alcohol use have a decreased cardiac ejection fraction. Because of the association between heavy alcohol use/alcohol use disorders and nicotine dependence, smoking-related comorbidities such as coronary heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) should also be considered. Preoperative laboratory studies should include electrolyte, liver and synthetic function tests, coagulation studies, and a complete blood count. Anemia is common in patients with alcohol dependence as well as decreased platelet count from alcohol-associated bone marrow suppression and splenic sequestration. It is also important to identify patients who are in recovery preoperatively because they may have concerns and questions about perioperative exposure to sedative hypnotics and opioid analgesics.

Management of Alcohol Withdrawal

Withdrawal symptoms may appear within hours of decreased intake; however, during the perioperative period, the administration of anesthetics, sedatives, and analgesics may delay the onset of withdrawal for up to 14 days. Because alcohol withdrawal is especially dangerous during the postoperative period, asymptomatic but at-risk patients should receive prophylactic treatment to prevent withdrawal.

Alcohol Use and Surgical Risk

Heavy alcohol use, even in the absence of clinical liver disease, is a dose-related independent risk factor for postoperative complications, most pronounced in groups who drank >60 g of alcohol (>4 drinks) per day. The postoperative complications reported were an increased rate of infection, bleeding, and delayed wound healing. Five possible pathologic mechanisms for the increased rate of postoperative complications include immune incompetence, subclinical cardiac insufficiency, hemostatic imbalances, abnormal stress response, and wound healing dysfunction. Abstinence before surgery decreases postoperative morbidity.

Alcoholic Liver Disease

The spectrum of liver disease associated with the spectrum of unhealthy alcohol use includes asymptomatic fatty liver, to acute hepatitis, and finally chronic cirrhosis. Each form of liver disease carries some degree of surgical risk and requires special preoperative considerations.

Alcoholic Fatty Liver

Patients with fatty liver seem to tolerate surgery well; however, there are no known studies evaluating perioperative risk in these patients. It is prudent to delay elective surgery until resolution of clinical signs and symptoms and, if possible, abstinence is achieved.

Alcoholic Hepatitis

Surgical risk is very high in this group, with 100% mortality rates reported in older series. Therefore, alcoholic hepatitis should be considered a contraindication to elective surgery. It is recommended that elective surgery be delayed until clinical and laboratory parameters normalize, sometimes taking up to 12 weeks.

Alcoholic Cirrhosis

The need for surgery is common in patients with cirrhosis, with up to 10% requiring a surgical procedure during the last 2 years of life. Depending on the stage of cirrhotic disease, surgery can be extremely risky. The most common causes of perioperative mortality in cirrhotic patients are sepsis, hemorrhage, and hepatorenal syndrome. Although currently used anesthetic agents are not hepatotoxic, surgical stress in itself causes hemodynamic changes in the liver resulting in increased risk for hepatic decompensation during surgical stress. Anesthetic agents decrease hepatic blood flow and therefore decrease hepatic oxygen uptake. Intraoperative traction on abdominal viscera may also decrease hepatic blood flow.

Effect of Cirrhosis on Surgical Risk

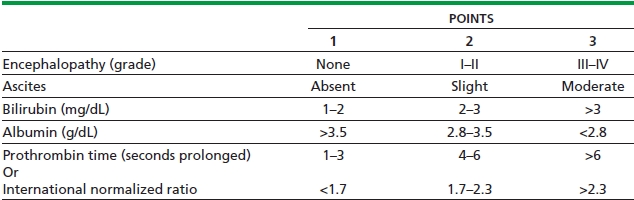

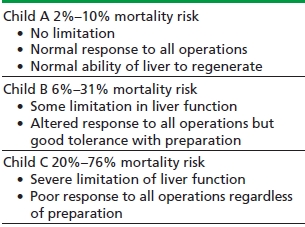

The preoperative factors associated with increased surgical morbidity and mortality include emergent surgery, upper abdominal surgery, poor hepatic synthetic function, anemia, ascites, malnutrition, and encephalopathy. These patients are at increased risk for un-controlled bleeding, infections, and delirium. Coagulopathies and thrombocytopenia result in difficult perioperative hemostasis. Ascites increases the risk of intra-abdominal infections, abdominal wound dehiscence, and abdominal wall herniation. Nutritional deficiencies result in poor wound healing and an increased risk of skin breakdown, and encephalopathy decreases the patient’s ability to effectively participate in postoperative rehabilitation. The action of anesthetic agents may be prolonged and increases the risk of delirium. In trying to risk stratify patient preoperatively, it is important to look for clinical signs of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. There are two scoring systems in use to predict whether patients with advance liver disease will survive surgery. Using a multivariable clinical assessment, the Pugh (modified Child and Turcotte) Classification (Table 84-1) stratifies cirrhotic patients into three classes based on “hepatic reserve” and therefore surgical risk. Using pooled surgical data, the Pugh Classification scheme has proven to be a good preoperative risk stratifier (Table 84-2). A second scoring system is the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD). It is used to prioritize patients for liver transplantation and, more recently, as a predictor of survival after nontransplant surgery. The MELD score is calculated using the patient’s international normalized ratio and serum creatinine and bilirubin. Because the MELD formula is complex, scores can be calculated by using an online MELD score calculator at http://www.unos.org/resources/meldpeldcalculator.asp.

TABLE 84-1. PUGH CLASSIFICATION (MODIFIED CHILD AND TURCOTTE CLASSIFICATION)

Class A 5–6 points

Class B 7–9 points

Class C 10–15 points

Adapted from Pugh RN, Murray Lyon IM, Dawson JL, et al. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973;60:646–649.

TABLE 84-2. CHILD CLASS, OPERATIVE RISK, AND OPERABILITY

Adapted from Stone HH. Preoperative and postoperative care. Surg Clin North Am 1977;57:409–419.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree