Surgical Anatomy of the Hernial Rings

Lee J. Skandalakis

David A. McClusky III

Petros Mirilas

Introduction

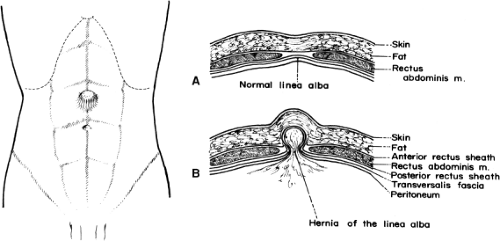

The purpose of this chapter is to present the anatomic entities related to the hernias that the general surgeon frequently encounters, and to highlight anatomic details that should be considered when performing hernia repair. Much of this chapter is dedicated to the features of the hernial rings within the anatomic regions addressed in this section of Mastery of Surgery, including the anterolateral abdominal wall, groin, pelvis and perineum. For those searching for a comprehensive overview of all known hernial rings that a general surgeon may encounter, including congenital and iatrogenic hernias, please refer to Table 1. For more information, we recommend Skandalakis’ Surgical Anatomy: The Embryologic and Anatomic Basis of Modern Surgery.

Table 1 Surgical Anatomy of Hernial Rings | |

|---|---|

|

Anterolateral Abdominal Wall

We agree with McVay that the terms anterolateral abdominal wall and posterolateral abdominal wall are more anatomically correct than are anterior and posterior abdominal wall; therefore, we have adopted that usage.

The boundaries of the anterolateral abdominal wall as described by McVay are as follow:

Above: xiphoid process and costal margins

Below, from medial to lateral:

Pubic symphysis

Inguinal ligament

Pubic crests

Iliac crests

Lateral: lateral margins are conventional vertical lines dropped from the costal margins to the most elevated portions of the iliac crests.

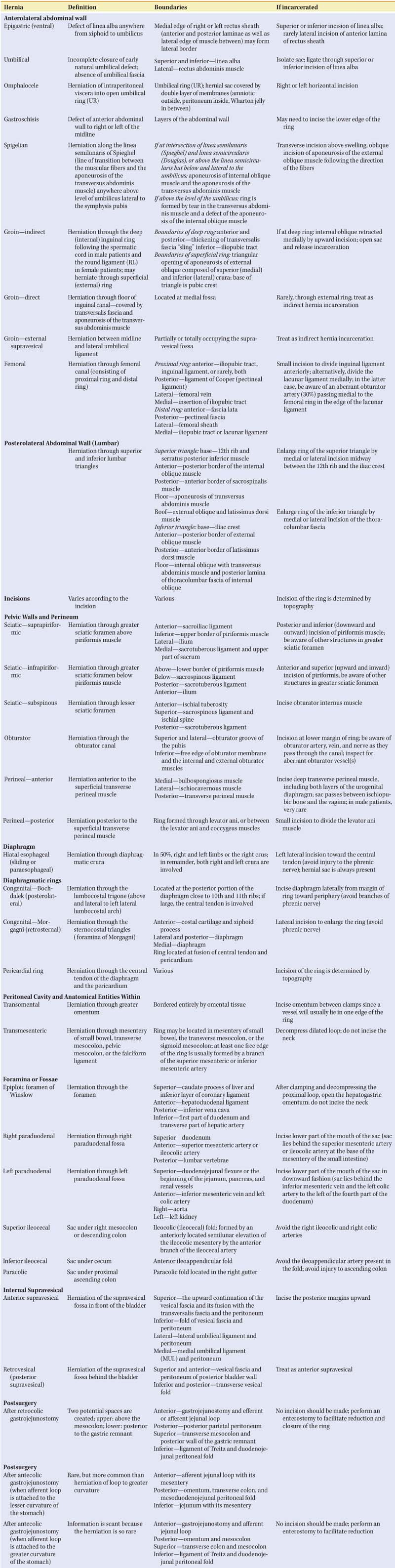

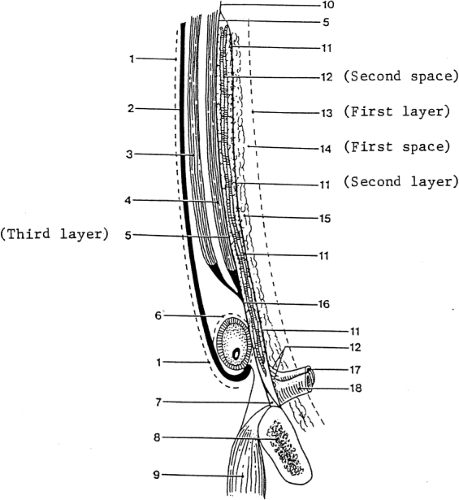

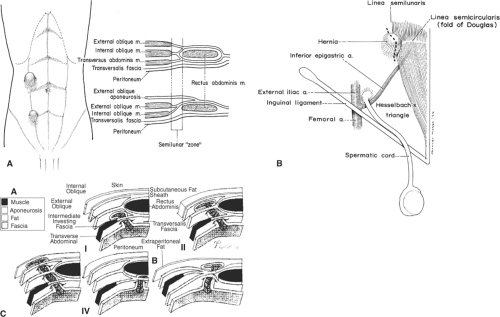

The anterolateral abdominal wall is divided into the well-known four quadrants by (a) a vertical line at the midline from the xiphoid process of the sternum, passing through the umbilicus, and terminating at the pubic symphysis, and (b) a horizontal line passing through the umbilicus. Figure 1 shows the layers of the anterolateral abdominal wall and inguinal area. Figure 2 shows the superficial and deep layers of both the anterolateral and the posterolateral abdominal wall.

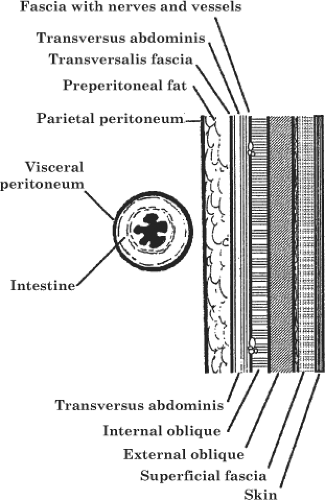

Epigastric Hernia

Epigastric hernia is known also as hernia of the linea alba or ventral hernia. The hernial ring is composed entirely of fibers of the linea alba. It may lie anywhere between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus (Fig. 3). The boundaries of the hernial ring depend on the formation of the linea alba by decussating fibers of the rectus sheath (Fig. 4).

It is likely that herniation is the result of an enlargement of the spaces existing between decussating tendinous fibers of the rectus sheath at the linea alba, especially at sites of passage of neurovascular bundles.

The medial edge of one or both (right/left) rectus muscles may form the lateral border of the hernial ring. If the defect is larger than 1.5 cm, the lateral border of the hernial ring may be formed not only by the anterior and posterior laminae of the rectus sheath, but also by the lateral edge of the muscle between.

A sac may be present at the site of weakness, or there may be a protrusion of preperitoneal fat without a sac. When

incarceration occurs, the ring may be enlarged surgically by superior or inferior incision of the linea alba. Occasionally, but rarely, a lateral incision of the anterior lamina of the rectus sheath may be necessary.

incarceration occurs, the ring may be enlarged surgically by superior or inferior incision of the linea alba. Occasionally, but rarely, a lateral incision of the anterior lamina of the rectus sheath may be necessary.

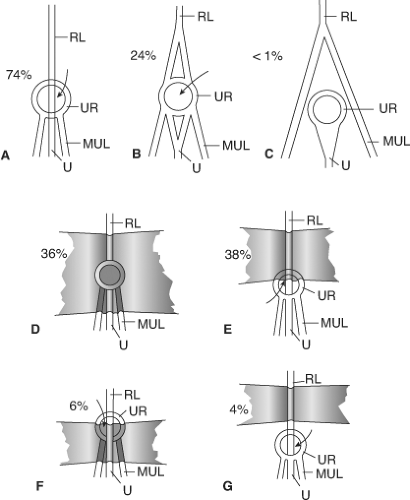

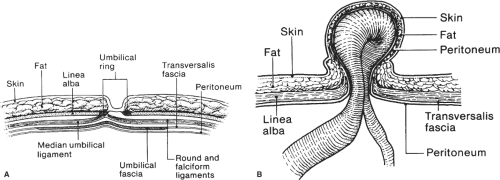

Umbilical Hernia

The work of Orda and Nathan concerning the umbilical structures is crucial to understanding the umbilical ring(s) (URs) and the formation of an umbilical hernia (Fig. 5). It is not within the scope of this chapter to describe the boundaries of all theoretically possible “rings” of umbilical hernia. We present only the most common because all defects result from the incomplete closure of the early natural umbilical defect and the absence of umbilical fascia. The formation of an umbilical hernia is an enigmatic and complex process from embryologic and anatomic standpoints (Fig. 6).

The possible boundaries of the UR are as follows: superior and inferior—the UR is related to the linea alba and to the rectus abdominis muscle and the rectus sheath on each lateral side (right and left). The hernial sac is tightly adherent to the umbilical skin. If the umbilical hernia is incarcerated, the sac should be carefully isolated. The ring should be incised as per epigastric hernia.

Spigelian Hernia

Protrusion of a peritoneal sac, an organ, or preperitoneal fat through a congenital or acquired defect in the spigelian aponeurosis is referred to as a spigelian hernia (hernia Spigeli). The spigelian aponeurosis is defined as the part of aponeurosis of the transverse abdominal muscle between the linea semilunaris laterally and the lateral edge of the rectus muscle medially. Spigelian hernias are located between the muscle layers of the abdominal wall along the semilunar line, and have been called lateral ventral, interparietal, intermuscular, or intramural hernias. Although also called “interstitial hernias,” they keep a prefixed location along the semilunar line (of Spieghel), and should be differentiated from interstitial hernias, which are also found between the different layers of abdominal muscle, but not limited to the spigelian aponeurosis.

Although named after Adriaan van der Spieghel, he only described the semilunar line (linea Spigeli) in 1645. Josef Klinkosch, in 1764, first defined the spigelian hernia as a defect in the semilunar line.

Embryologically, spigelian hernias may represent the clinical outcome of weak areas in continuation of aponeuroses of layered abdominal muscles as they develop separately in the mesenchyme of the somatopleure, originating from the invading and fusing myotomes.

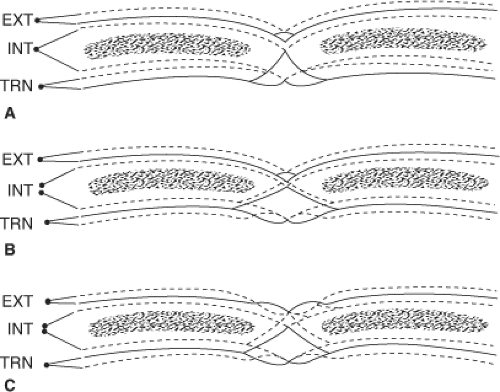

A spigelian hernia must be conceived of first as a protrusion through an opening of the transversalis aponeurosis. The opening also includes the transversalis fascia, which is the inner investing fascia of the transverse muscle and aponeurosis. Then, the hernia protrudes toward the aponeurosis of the internal oblique. This aponeurosis may also rupture, but usually the aponeurosis of the external oblique is too strong to be penetrated by the hernia. This partial abdominal wall hernia presents anatomical challenges that cause difficulties in diagnosis. The space between the two oblique muscles is loose; thus, the sac usually expands in the space and adopts a T-shape or mushroom-like appearance. Possible locations of the sac are shown in Figure 7). Mirilas et al. (2006) offered a thorough review on the surgical anatomy, embryology, and technique of repair.

Groin Hernia

The anatomy of the inguinal region is complex, with multiple entities joining to form the supportive foundation of the inferior anterolateral abdominal wall as it attaches

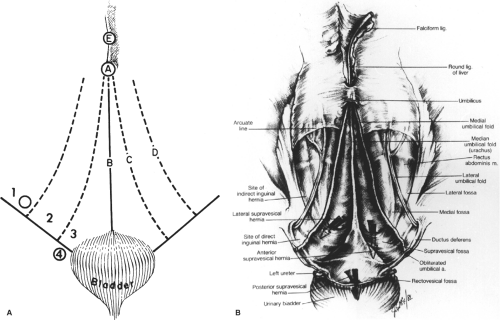

to the pubic tubercle, pelvic rami, and the anterior superior iliac spine. Four groin hernias are encountered in this region: indirect inguinal, direct inguinal, external (anterior) supravesical, and femoral. All of these originate from the fossae of the anterolateral abdominal wall (Fig. 8). To understand these hernias and the formation of the rings, knowledge of the anatomy of the groin and inguinal canal is essential. Herein, we provide an overview of the structural entities encountered in the groin, and their relationship in the formation of these four hernias.

to the pubic tubercle, pelvic rami, and the anterior superior iliac spine. Four groin hernias are encountered in this region: indirect inguinal, direct inguinal, external (anterior) supravesical, and femoral. All of these originate from the fossae of the anterolateral abdominal wall (Fig. 8). To understand these hernias and the formation of the rings, knowledge of the anatomy of the groin and inguinal canal is essential. Herein, we provide an overview of the structural entities encountered in the groin, and their relationship in the formation of these four hernias.

Anatomical Entities of the Groin

Aponeurosis of the External Oblique Muscle

Below the arcuate line, this aponeurosis joins with the aponeuroses of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles to form the anterior layer of the rectus sheath. This aponeurosis contributes to the inguinal ligament (Poupart’s), the lacunar ligament (Gimbernat’s), the reflected inguinal ligament (Colles’), and the pectineal ligament (Cooper’s). The pectineal ligament is also formed from tendinous fibers of the internal oblique, transversus, and pectineus muscles.

Inguinal Ligament (Poupart’s)

The inguinal ligament is the thickened lower part of the external oblique aponeurosis

from the anterior superior iliac spine laterally to the superior ramus of the pubis. The middle one-third has a free edge. The lateral two-thirds are the underlying iliopsoas muscle and fascia (Fig. 9).

from the anterior superior iliac spine laterally to the superior ramus of the pubis. The middle one-third has a free edge. The lateral two-thirds are the underlying iliopsoas muscle and fascia (Fig. 9).

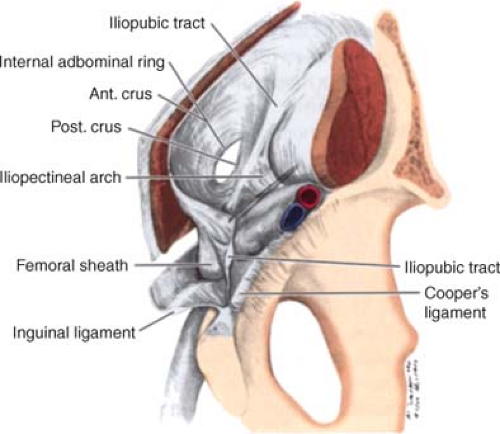

Iliopectineal Arch

The iliopectineal arch is a medial thickening of the iliac fascia deep to the inguinal ligament. The arch extends from the iliopubic tract towards the anterior border of the femoral canal (Fig. 10)

Iliopubic Tract

The iliopubic tract is the aponeurotic band extending from the anterior inferior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle. It forms part of a deep musculoaponeurotic layer that reinforces the inguinal canal behind the transversus abdominis muscle and aponeurosis and the transversalis fascia. The tract passes medially, contributing to the inferior border of the internal ring. It crosses the femoral vessels to form the anterior margin of the femoral sheath, together with the transversalis fascia. The tract curves around the medial surface of the femoral sheath to attach to the pectineal ligament. It can be confused with the inguinal ligament (Fig. 10).

Lacunar Ligament (Gimbernat’s)

Pectineal Ligament (Cooper’s)

It is regarded as a periosteal extension of the lacunar ligament along the pectineal line. The pectineal ligament is a thick, strong tendinous band formed principally by tendinous fibers of the lacunar ligament and aponeurotic fibers of the internal oblique, transversus abdominis, and pectineus muscles, and, with variation, the inguinal falx. It covers the periosteum of the superior pubic ramus, the pectinate line and the upper part of the pectinate fascia. It is often used in surgical hernia repair, because it is a firm anchor for muscular, tendinous and fascial layers of the groin (Figs. 10 and 11).

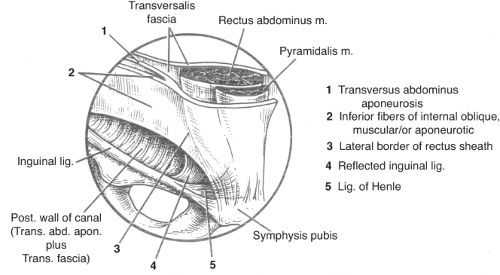

Conjoined Tendon (Area)

By definition, the conjoined tendon is the fusion of the internal oblique aponeurosis with similar fibers from the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle just as they insert on the pubic tubercle, the pectineal ligament, and the superior ramus of the pubis. This configuration has traditionally been referred to as the conjoined tendon. As described, however, this is rarely encountered; it is found in <5% of cases. The term “conjoined area” may be more appropriate. This usage has practical application to this region, as it also allows inclusion to this entity to the falx inguinalis (Henle’s ligament), the inferiormedial fibers of

the internal oblique, the reflected inguinal ligament, and the lateral border of the rectus sheath (Fig. 9).

the internal oblique, the reflected inguinal ligament, and the lateral border of the rectus sheath (Fig. 9).

Falx Inguinalis (Henle’s)

Henle’s ligament is the lateral, vertical expansion of the rectus sheath that inserts on the pectin of the pubis. It is present in 30% to 50% of individuals and is fused with the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascia.

Reflected Inguinal Ligament (Colles’)

Colles’ ligament is formed by aponeurotic fibers from the lateral crus of the external ring, which pass medially and upwards, behind the medial crus, to blend with the opposite external oblique aponeurosis. (Fig. 9).

Arch of the Transversus Abdominis

The inferior portion of the transversus abdominis becomes less muscular and more aponeurotic as it approaches the rectus sheath. Close to the deep ring, it is covered by the more muscular arch of the internal oblique muscle.

Transversalis Fascia

Although the name transversalis fascia may be restricted to the internal fascia lining the transversus abdominis muscle, it is often applied to the entire connective tissue sheet lining the abdominal cavity. In the latter sense, it is a fascial layer covering muscles, aponeuroses, ligaments, and bones. In the inguinal area, the transversalis fascia is bilaminar, enveloping the inferior epigastric vessels (Fig 1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree