Superficial Groin Dissection

Laura A. Adam

Neal Wilkinson

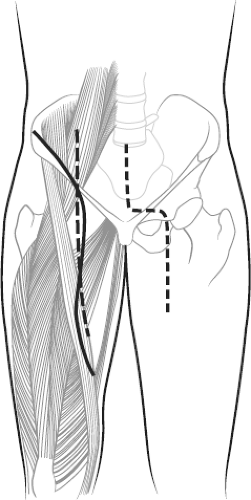

Avariety of terms are used to describe lymphadenectomy of the inguinal and ilioinguinal regions. In this chapter, we will use the terms superficial and deep. A superficial dissection includes the lymph node basins of the inguinal ligament, saphenous vein, and femoral vessels. Cloquet’s node is typically removed during a superficial dissection (Fig. 119.1). A deep dissection includes the lymph node basins extending along the course of external, internal, and common iliac vessels. In addition, deep dissection may include lymph nodes within the obturator canal.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified ilioinguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy as a “COMPLEX” procedure.

SUPERFICIAL REGION

Inguinal

Saphenous

Femoral

Cloquet’s node

DEEP REGION

External iliac

Internal iliac

Common iliac

Obturator

When both the superficial and deep regions are removed, we will refer to a superficial and deep dissection, realizing that the term radical is occasionally used in this setting. The proximal extent or pelvic component of the dissection may vary depending on the pathology being treated and must be clearly stated in the operative note instead of using vague terms such as deep or radical.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE

Superficial Inguinal Dissection

Supine position with leg externally rotated and knee slightly flexed

Lazy S–shaped incision from anterosuperior iliac spine to medial thigh

Proximal extent used primarily for deep dissection or in obese patients

Develop flaps medially and laterally just above superficial fascia; to lateral border of sartorius muscle and medial border of gracilis muscle

Avoid lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

Ligate tributaries of saphenous vein entering field and saphenous vein itself entering inferior aspect of field

Sweep fatty node-bearing tissue cephalad to saphenofemoral junction and ligate and divide saphenous vein (oversew femoral end)

Divide or retract inguinal ligament to expose femoral canal

Remove nodal tissue; label the highest node as Cloquet’s node and submit separately

Deep Inguinal Ligament

Place deep self-retaining retractors and divide external oblique aponeurosis

Divide inguinal ligament

Displace spermatic cord (in males) medially and divide the inferior epigastric vessels

Gently displace peritoneum medially to expose retroperitoneal structures

Begin laterally on the pelvic sidewall and sweep nodes and associated tissues medial

Mobilize rectum and bladder medially and retract these behind moist packs

Obturator node dissection can be performed by following the obturator nerve and artery

Obtain hemostasis and reapproximate the inguinal ligament and abdominal wall structures

Detach sartorius high on the anterosuperior iliac spine

Mobilize it, rotating it to fit into the space over the femoral vessels

Suture the sartorius muscle to the inguinal ligament

Place closed-suction drains and close

Close incision in layers

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Injury to lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

Injury to femoral vein or femoral nerve

Injury to obturator nerve

Injury to pelvic nerve plexus

Lymphocele or lymphedema

Skin necrosis

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Inguinal Lymph Nodes

Superficial inguinal lymph nodes

Deep inguinal lymph nodes

Node of Cloquet

Iliac lymph nodes

Obturator Lymph Nodes

Obturator foramen

Obturator canal

Anterosuperior iliac spine

Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

Inguinal ligament

Pubic tubercle

External oblique aponeurosis

Fascia lata

Femoral Triangle

Femoral nerve

Femoral artery

Femoral vein

Saphenous Vein

Saphenofemoral junction

Adductor longus muscle

Sartorius muscle

Figure 119.1 Regional anatomy. The nodes encompassed during a superficial dissection are shown on the right-hand side of the figure, and the nodes taken during deep dissection are shown on the left. |

The superficial and deep inguinal lymph node dissection is most commonly performed for cutaneous malignancies of the lower extremity, lower abdomen, and flank. Melanoma remains the most common indication and the majority will have been localized to the region by sentinel node mapping techniques. Additional indications include penile, distal urethral, scrotal, vulvar, anal, and anal canal cancers. The pelvic lymphadenectomy for gynecologic pathology may include many of the same regional lymph node basins, but is approached through a lower midline incision and will not be covered in this chapter.

These procedures carry a significant risk of local morbidity, including skin flap necrosis, wound infection, seroma formation, and lymphedema. For melanoma, the procedure should only be performed for documented disease in the region commonly described as a “therapeutic” lymphadenectomy. Sentinel lymph node staging, computed tomography, or ultrasound-directed fine-needle aspiration, and now positron emission tomography can be used to preoperatively stage the region and has replaced elective nodal dissection for melanoma.

Incision and Elevation of Flaps: Superficial and Deep Regions (Fig. 119.2)

Technical Points

After induction of anesthesia, the patient is positioned supine with the leg externally rotated and the knee slightly flexed to

improve medial exposure. In larger patients, placing a bump under the thigh may further facilitate exposure. Preoperative antibiotics are frequently given despite the procedure being a Class I (infection classification) case. Most wound complications are related to skin flap necrosis and lymphedema. These are not likely to be influenced by antibiotics, and randomized controlled trials have questioned their efficacy in preventing wound complications. However, because of these high wound complication rates, it is reasonable to provide a short course of antibiotics directed toward common skin flora. A Foley catheter and sequential compression devices are typically used. Muscle paralysis should be minimized until the femoral nerve is clearly identified. The skin preparation and draping should include lower abdomen to knee with wide medial and lateral exposure.

improve medial exposure. In larger patients, placing a bump under the thigh may further facilitate exposure. Preoperative antibiotics are frequently given despite the procedure being a Class I (infection classification) case. Most wound complications are related to skin flap necrosis and lymphedema. These are not likely to be influenced by antibiotics, and randomized controlled trials have questioned their efficacy in preventing wound complications. However, because of these high wound complication rates, it is reasonable to provide a short course of antibiotics directed toward common skin flora. A Foley catheter and sequential compression devices are typically used. Muscle paralysis should be minimized until the femoral nerve is clearly identified. The skin preparation and draping should include lower abdomen to knee with wide medial and lateral exposure.

The inferior aspect of the incision is placed directly over the femoral vessels and should extend inferiorly to the convergence of the sartorius and femoral vessels. The superior aspect of the incision may vary based on surgeon choice, patient body habitus, and anticipated proximal extent of the dissection. We prefer a lazy S–shaped incision from the anterosuperior iliac spine to the medial thigh with the middle portion overlying the bottom of the inguinal ligament. The abdominal pannus in large body habitus patients can be rotated medially and elevated superiorly to provide better visualization. An alternate straight vertical incision traversing the inguinal ligament onto the lower abdomen works well in thin patients. If a previous sentinel lymph node biopsy site exists, it should be included in the incision. The proximal extent of the incision can vary depending on the proximal extent of the dissection and will need to be longer if a deep dissection is to be done. The abdominoinguinal incision is seldom indicated to gain wider access to the pelvis but can provide wide exposure of the entire internal pelvis when clinically indicated: Proximal control of vessels, difficult bleeding, or bulky adenopathy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree